.

.

Brianmcmillen, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

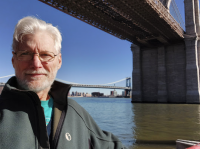

Sheila Jordan, 1985

.

___

.

Hippie In a Jazz Club

by Scott Oglesby

.

…..No, this is not a joke. On a memorable night in 1980 a hippie did stroll into a jazz club. But it wasn’t just any ol’ club, it was the fabled Keystone Korner in San Francisco’s North Beach. Seating only about 100 bodies, it had never been a viable music venue. But somehow, from 1972 to 1983, it managed to host some of the best musicians in the country, becoming the West Coast’s go-to club for live jazz recordings. The famed pianist Mary Lou Williams hailed it as the “Birdland of the 70’s”.

…..I had learned all of this from Lorraine, one of my servers at Simple Pleasures, a Café on Balboa Street that I owned and operated at the time. Lorraine also waitressed at Keystone several nights a week and reveled in being one of its “jazz ambassadors.” On one particular day, a Tuesday in 1980, she insisted that I go to Keystone that night because Sheila Jordan was the headliner. She also told me that Sheila had been voted Downbeat’s best female vocalist several times in the last decade.

Brianmcmillen, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

The Keystone Korner, 1982

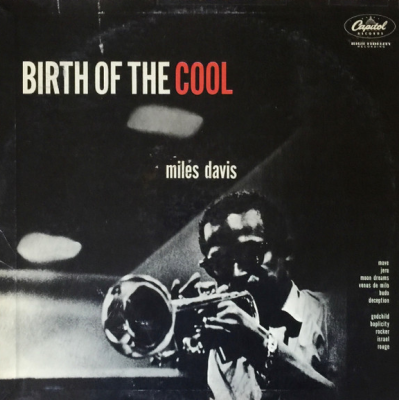

…..I didn’t argue. I had only recently expanded my musical boundaries from folk-rock and Santana to Grover Washington funk and was slowly graduating to the more serious stuff from Stan Getz, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Mark Murphy, and Miles. I was also into Billie, Ella, and Sarah.

…..I drove down to Keystone alone that night and scored a small table in the second row. I was not to be disappointed—taking the stage with a back-up trio of double bass, piano and drums, Sheila was impeccable. Her specialty was be-bop and scat, but she was also a distinctive interpreter of classic jazz ballads. Amidst pin-drop silence, she would marry the mike, close her eyes through entire songs, and transport the audience into dreamy musical trances.

…..If you’re thinking now that I was that “hippie in a jazz club,” you’d be wrong. That dishonor would belong to a different hippie that night—a young man who showed up in the middle of Sheila’s set. She was singing one of her fragile extended ballads when he suddenly appeared from the bar area and then breezed down the short aisle beside the stage. On the way to the bathroom in the back, I assumed. But no—when he reached the steps, he turned and marched up onto the stage behind the band. He then weaved with casual resolve between the piano player and bassist, brushed within a foot of Sheila, crooning with her eyes wide shut, and hopped off into an empty chair at the table in front of me.

…..Many mouths fell open, including mine. Her band, however, had not missed a note or a beat. They continued to accompany oblivious Sheila as she delicately grooved on through the most intimate part of her ballad.

…..Jazz is not punk rock—no diving into thrashing mosh pits; no leaping onstage to boogaloo with the band; no raised arms swaying with lit lighters. Jazz is cool, calm, and cocktails; there’s no marching across a live stage to get a good seat.

…..But was this even real? Had we seen what we had just seen? The bands’ faces registered the same disbelief, but they quickly evolved to livid. Lucky Sheila, she had avoided wholesale the dramatic trauma of this brief but crazy intrusion.

…..But we, the audience, were trapped—shocked and reluctant witnesses to an artistic violation of the worst sort. As you might imagine, our applause was hesitant and sketchy when Sheila finished her number—excepting that hippie in front of me who was raising all kinds of adulatory hell. I dubbed him a hippie not because of his attire or hair length, both similar to mine, but in recognition of his audacious stroll, not to mention his goofy grin and plodding gait. All clues that he was peaking on a kite-flying high from some seriously strong substance. I could relate, and I couldn’t help but feel complicit because he looked like one of my tribe.

…..Meanwhile, the band had herded Sheila into a huddle onstage where, with dramatic finger-pointing, they filled her in about the stroll this fool in the front row had taken. As you would expect, they refused to continue playing until said fool was eighty-sixed. But this was a small jazz club, not a rock concert, and there were no Hell’s Angels to drag him out, not even a hulky bouncer to frog-walk him to the door. It took a mild-mannered manager a good five minutes to coax the tripping kid out of the club while the band took the same five backstage.

…..When Sheila and her trio returned, proper decorum was quickly established, and they finished their set without incident. Their music was world-class, and after another hour plus an encore, they left the stage. To my regret, I was too shy to hang out and possibly meet Sheila. I drove home that night still a little weirded out, but mostly jazzed and happy, the hippie intruder just a lingering bad taste. It was a musical nugget that would have a surprising payoff down the road.

.

…..Eight years down the road to be exact, all the way to the East Coast where I had moved into an upstate N.Y. farmhouse with my older sister, Rhonda. I was spending a lot of time on the screen porch trying to suppress the confused nostalgia about my former life in San Francisco.

…..My default reverie ended when Rhonda wheeled her old Volvo up the driveway, returning from errands in town. After parking next to the house, she breezed by me on the porch, a liter of Grigio in her hand. On her way to the kitchen, she casually mentioned a neighbor nearby whom I had never met—a female jazz singer—and that she’d just seen a car in her driveway.

…..“A jazz singer, really…a woman?” I asked.

…..“Yeah,” she said, “Sheila something.”

…..My mind did a loop. Jazz singer…Sheila? No way, I thought. I was afraid to ask, but I had to. “Uh… wouldn’t be Jordan, would it?”

…..“Yeah, I think that’s it, Sheila Jordan…You know her?”

…..I was speechless. Had my musing about California conjured this up? I rushed into the kitchen in gush mode, waxing on Sheila’s revered standing in the jazz world, her scat styling; and of course, that I had seen her perform at Keystone and stupidly flubbed my chance to meet her. But now I would have a chance for a redo. My sister was intrigued, but she had only spoken with her once; still I persuaded her to call Sheila on the spot. And she did, while I eavesdropped nervously, shuffling back and forth. After a short chat, our famous neighbor invited us to come over anytime.

.

…..I was giddy the following day as we drove the short half-mile to Sheila’s old farmhouse, a weathered affair like ours, from the 1800s. She greeted us at the door as if we were old friends. She was shorter than I remembered, but her brown hair was in the same ‘do as that night at Keystone, a fifties bob with bangs. She also had the rosiest cheeks I’d ever seen and a chirpy vibe to match. She chattered on as we got a ten-cent tour of her redone kitchen, similar to ours but more upscale.

…..Then, she said, “Oh, follow me…Mark is here.”

…..Rhonda and I swapped curious looks as we trailed her into the parlor where the first thing I saw was a full-size glossy-white grand piano, glistening in the light from a table lamp. And then I saw sitting at its bench was Mark Murphy, the king of scat and be-bop, multiple Downbeat winner and probably the best male jazz singer alive. So there we were—in the same room with two jazz legends. Sheila introduced him, and he swiveled off the bench, smiled big, and with gracious charm shook both our hands.

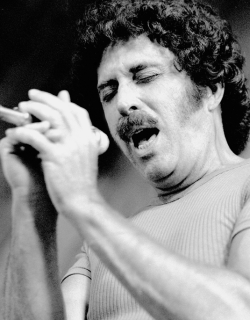

Brianmcmillen, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Mark Murphy, 1980

…..He appeared to be in his sixties, about Sheila’s age, and though his name was Murphy, he looked Mediterranean, with a face carved by some Italian master. We began chit-chatting right away and I was surprised to find him strikingly effeminate, and suddenly, I was aware that he was quite likely gay. This relaxed me immensely—a carryover from my acting history and happy immersion in the queer community of musical comedy. I was surprised because until recently, being “out” wasn’t that common in jazz circles, and at the time I was unaware of his own background in theater. Whatever, my new realization seemed to goose my groupie affinity, so much so that I think it annoyed my sister—a singer-songwriter herself, she was not a jazz weenie and had never seen either perform.

…..Pretty soon though, my fanboy jitters calmed down and I was blabbing on about seeing him at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco. Seems we had lived there at the same time, while he and Sheila had been friends for the last thirty years, both now residing in New York. This spurred lots of backstage stories and then out of the blue, Mark went off on a popular Bay area vocal group that he and Sheila had seen perform recently. They were incensed that the group had sung their entire set off-pitch, the name of the group escaping them both.

…..“Could be Dan Hicks and the Hot Licks,” I suggested.

…..“That’s them!” They shouted in unison. Everyone laughed, but soon I was explaining that I knew the group well and that their consistently flat vocals were evidently just a bold style choice. Needless to say, the jazz icons weren’t buying it. And I got it—it was kind of like asking classical musicians to accept artistically that female cellist from Little Rock who performed topless in the seventies.

…..Rhonda has told me that Mark and Sheila both played the piano and sang that evening, but I honestly don’t remember. I was starstruck and laser-focused on being viewed as a neighbor, not just another groupie; I hadn’t even brought any CDs for her to autograph. I was also nervous to ask about that tripping kid at Keystone Korner years ago. God knows how many club dates Sheila had performed since, but finally, I brought it up.

…..“Sheila, do you remember once when you had a gig at Keystone, probably seven or eight years ago, and uh…this crazy kid walked onstage, right in the middle of—”

…..“Omigod,” she blurted, “you were there that night!?”

…..“Yeah,” I chuckled, “it was the first time I ever saw you in person.”

…..Sheila was on her feet by then, excited by our oblique connection and pressing for every detail. I understood. She explained that the accounts from her band that night was all she knew—placing her at the centerpiece of a drama that she literally never saw. I was suddenly in that old parable describing an elephant to a blind person.

…..To my surprise, Mark had heard about this before from Sheila, but I was compelled to tell the incident as seen from the audience. I really couldn’t add much, but I hoped that sharing my version would put another piece into a timeworn puzzle. Amidst a flurry of omigods, we buzzed about it for a good ten minutes. Everyone agreed that my verdict of drug-related behavior was probably right-on. All the more interesting given that Mark and Sheila had by now both become teetotalers. Not so for my sister and me, and after a few more spirited but sober exchanges, we said our goodbyes and drove home to digest the evening with that bottle of Grigio.

.

…..It was only a few years later when the loss of family and musical friends would begin to take a toll on me. That’s when I heard from Sheila that Mark Murphy had passed away. I had chatted with him in New York only a few months earlier after a showcase of his students from his vocalese workshop at The New School. He probably didn’t remember me from our brief “hang out” together at Sheila’s but he faked it like a pro. Mark’s passing also highlighted my regret that I had recently missed Sheila’s ninetieth birthday gig at Birdland.

…..The following Sunday, I would be sitting with a large audience at Mark’s memorial at Saint Peter’s on Fifth Ave, a famous venue for jazz artists. Sheila was in the pulpit area with Mark’s newest protégé, vocalist Kurt Elling, and once again, my appreciation of jazz was about to take another giant step. There were many adoring testaments that afternoon, but the essence of Mark’s art and influence was delivered in song by Sheila and then in spades by Kurt, the embodiment of Mark’s legacy. His performance foretold the torch hand-off to the new “best male jazz singer” alive.

…..Except for a few shared meals, I had rarely seen Sheila since that night at her house with Mark. She was usually off on world tours performing and teaching jazz workshops, but one year, she hosted one locally at a neighbor’s house. Green with envy, I had listened to her students, a mix of types and ages, sing jazz standards, backed-up by piano and bass. I had heard about the class too late to sign up, although I might not have been that brave—my last voice lesson was in the seventies, and my folkie four-chord songs were a far cry from jazz vocalizing.

…..You would think that my love of jazz would have inspired me more, especially given that I had easy access to pianos my entire life. But I never took it further than one-hand riffing to blues albums or tunes on the radio, and then only after enough booze and weed to tap down ingrained childhood dogma that “only girls and sissies play piano.” It had always been safer to kick-back and listen to pianist Marian McPartland’s radio show where jazz-greats joined her for duets.

…..As I sat there at Saint Peters, I also thought of my belated discovery of the late jazz diva, Abbey Lincoln, a few years earlier. She had enjoyed an illustrious fifty-year career, performing with literally everybody, even starring in some cheesy movies, including one acclaimed film with Sidney Poitier. I remember being ecstatic upon learning that she resided in the same Manhattan nursing home as my wife’s father, himself an accomplished classical pianist. Unfortunately, my hope to meet her and introduce them was dashed when a nurse told me that, sadly, it wouldn’t be possible. Dementia, I had assumed, chalking up another near miss.

…..As the years rolled by, time had begun to show me less patience, and somewhere in the midst of those near misses, I began thinking about seeing Sheila and that hippie kid who had careened onto Keystone’s stage in San Francisco forty years earlier. There had been so many moments when I felt that I was like him, a voyeur stumbling around among true artists; that I, too, had failed in a profound way—to respect art, the making of art, the artists themselves. That I was stuck, kicking at the wheels of those passing me by. This was hogwash, of course, misdirected and fleeting, thank God. My dearth of self-respect was the ugly voice I was hearing. Lucky for me, maturity and old age was finally dragging me to a place where I recognized self-indulgent folly.

…..I consoled myself with the reasoning that artistic souls had always suffered greatly when they’d been unable to find an appropriate palette, measured success, or some kind of recognition. I and many other self-proclaimed under-achievers fall into this category. At some point, life-acceptance must take place; only then will we recognize that the artist label is just an external horn to blow. Seeking the truthy whispers from our inner- selves, a better alternative. I often remind myself that Van Gogh never sold a painting, a faux pas, for sure; and my classically trained wife informs me that when Bach submitted his Brandenburg Concertos as his job application, he didn’t even get a call-back. The rest is history.

…..But of course, all of that happened long before jazz was let loose in the musical universe. So for sure, I’ll remain thankful for my Bach on Sunday mornings; and I’ll be keeping both of my ears too, thank you very much—all the better for listening to Kurt, Sheila, Abbey, and Mark, or maybe Billie on dark rainy nights.

.

.

___

.

.

Scott Oglesby began as a reader for Bellevue Literary Review (BLR) before becoming assistant non-fiction editor in 2018. A New York City transplant from Louisiana, his varied history includes stints as a disability analyst, actor, singer, photographer, teacher, homemaker, and café-owner, all before publishing his first novel, Riding High. ( www.ridinghigh.net ).

He has also written for Manhattan weeklies: the West Side Spirit, the Villager, and Village Sun. The literary review, Gravel, published his story, Divorcing Rhonda, and his (BLR) essay, The Best That Love Could, was also produced as a podcast. His critique of David Amram’s book, Upbeat, was in American Book Review. Outpost 19 published an outtake from chapter one of his memoir-in-progress in their August 2023 anthology — Rooted 2: The Best New Arboreal Nonfiction. And Red Dirt Press published two of his nonfiction pieces online in 2023. Currently, like every other guy he knows with white hair, he’s writing a memoir.

Click here to visit Sheila Jordan’s website

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

Click here to read “Rudy Van Gelder: Jazz Music’s Recording Angel” – an essay by Joel Lewis

Click here to read “Gone Guy: Jazz’s Unsung Dodo Marmarosa,” by Michael Zimecki

Click here to read “Like a Girl Saying Yes: The Sound of Bix” – an essay by Malcolm McCollum

Click here to read more True Jazz Stories

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here for details about the upcoming 68th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

.

.

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

Terrific piece. I love how it focuses and then broadens to encompass all artists and the truth of anyone endeavoring in any art, while sticking to the authors own life as well. Evocative of the time, music, plus its humorous.

“Hippie In a Jazz Club” by Scott Oglesby was great fun to read and opens a window on jazz performers’ lives, including occasional conflicts with selfish fans. Scott Oglesby transports the reader into scat-singing legend Sheila Jordan’s NY farmhouse on an inspired day she was sharing with another scat-singing legend, Mike Murphy.