.

.

Photo by Francis Wolff © Blue Note Records

.

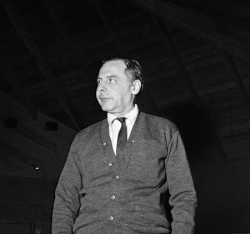

Rudy Van Gelder, Jazz Music’s Recording Angel

by Joel Lewis

.

.

___

.

.

“Hey Rudy, put this on the record … all of it!”

– Miles Davis, from studio chatter during the recording of “The Man I Love” (Take 1) for the December, 1954 album, Miles Davis All Stars (Volume 2)

.

(Listen to the track) [Universal Music Group]

.

.

1.

…..Sylvan Avenue in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey is referred to by realtors as the “Billion Dollar Mile” because of the large number of corporate headquarters and high-end car dealerships that line this section of Route 9W. CNBC World Headquarters along with the North American headquarters of the LG Corporation, Unilever, Maserati and Ferrari are located here.

…..At the northern end of this gilded corridor is a small sign that indicates an address, 455 Sylvan Avenue, and a sign that warns against using the long driveway as a U-Turn turnabout. At the end of the driveway is an unusual looking building that stands out from its shiny corporate box neighbors. To the uninitiated, the small building appears to be a home or some sort of workshop. To jazz fans, it is holy ground, a place where tone scientists of the stature of John Coltrane, Art Blakey, Freddie Hubbard & Wayne Shorter recorded their classic texts of sound.

…..Rudy Van Gelder, the proprietor of this studio, was perhaps the only sound engineer, save for Atlantic Record’s Tom Dowd, to have name recognition among the general music public. And, as he always pointed out in interviews, he was a recording engineer, not a producer. He did not book musicians, organize sessions or even select the takes that shape the completed album. For over 60 years, he devoted himself to the language of sound. And although he recorded everything from glee clubs to classical music, he was best known for recording jazz – specifically the musicians associated with Blue Note and Prestige records.

…..Born in Jersey City on November 2, 1924, Van Gelder grew up a fan of the big bands of the era, even playing trumpet in his high school’s marching band. He was already fascinated by electronic technology – he had a ham radio license (W2TMD) and owned a portable acetate-recording machine. While attending optometry school in Philadelphia, Van Gelder and a friend were able to tour the studios of WCAU, the CBS affiliate in the city. As Van Gelder told Jazz Wax blogger Marc Myers, “A powerful feeling swept over me. The music, the equipment’s design, the seriousness of the place—I knew I wanted to spend my career in that type of environment.”

…..Right after graduating from college, Van Gelder opened an optometry practice in Teaneck, NJ. But after hours, he was recording local musicians in his parents’ living room. In an era before the availability of quality home recording devices, local recording studios were common. Van Gelder’s long association with Blue Note records came through his recording a young baritone saxophonist named Gil Melle’ for a producer named Gus Statiras. When Statiras attempted to shop these sessions to Blue Note, co-owner Alfred Lion was taken by the sound achieved at the studio in suburban New Jersey. Soon, Blue Note was regularly using the studio, along with rival labels such as Prestige, Savoy and Verve. Blue Note’s other boss, Francis Wolf, would regularly photograph these sessions – the incongruous image of sunglass wearing, sharply dressed Black musicians performing in what looked like someone’s living room. Van Gelder’s parents must have been remarkably tolerant and supportive, as these recording sessions were happening most evenings as Van Gelder’s reputation as a recording engineer spread throughout the jazz community. Neighbors rarely complained, either.

…..Despite a busy schedule that caused Van Gelder to assign specific recording days for the labels booking studio time, he continued his optometry practice until the early 60’s– mostly to raise capital for studio equipment. Van Gelder swore by Neumann condenser microphones and was one of the first American engineers to use these German-made devices. He always used the most up to date equipment available – he was one of the first engineers to switch to tape as a recording medium and when digital recording became the dominant mode, he mastered it and proceeded to digitalize hundreds of the classic albums he recorded in the 50s and sixties.

.

2.

.

…..“Some musicians sounded more real on your recordings than they would in a club,” the pianist and writer Ben Sidran ventured in 1985 in a rare interview with Mr. Van Gelder, who seemed to agree. He replied, “A great photographer will really create his image, and not just capture a particular situation.”

…..Jazz fans revere Van Gelder not just because he recorded some of the great artists of his generation, but because of the way he made them sound. It is a bit indefinable, but what Van Gelder did was create a stronger sense of depth, presence and immediacy in the music than was previously heard on record. He was notoriously mum on his trade secrets and apparently took them with him to the grave. “When people talk about my albums, they often say the music has ‘space.’ I tried to reproduce a sense of space in the overall sound picture.” he told an interviewer, adding: “I used specific microphones located in places that allowed the musicians to sound as though they were playing from different locations in the room, which in reality they were. This created a sensation of dimension and depth.”

…..Apparently, part of the magic was in his microphone placements. If a musician attempted to adjust one of them, Van Gelder would storm out of the recording booth to both scold the musician and to reconfigure the microphone. He wore gloves when he recorded (plain old brown work gloves and not the white gloves that seem to be part of any anecdote about recording at Van Gelder Studio).

…..Rudy Van Gelder was the only major engineer of his day to task himself with the process of mastering his sessions. Working with the producer, he would edit the tapes to remove bad notes and edit solos. A tape was created with the “master” takes in the order the listener would hear them on vinyl. He then used a Scully lathe which mastered the tape onto a disk that would eventually be nickel plated and then used to press the album. It was a very precise and labor-intensive process, but Van Gelder felt that if his name was listed as engineer, he needed to see the entire process through.

.

3.

.

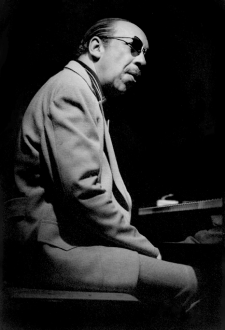

…..Although Van Gelder engineered for many labels, he is best known for his work with the Blue Note and Prestige labels. The former was begun in 1939 by two German émigrés Alfred Lion and Max Margulis, who came to the US because of the threat of Nazism. Margulis, who provided the seed money to get the label off the ground, soon left the label and another refugee fleeing Nazism, Francis Wolff, joined with Lion. Early Blue Note recordings were of classic jazz stars like Meade Luxe Lewis, Albert Ammons and Sidney Bechet. It was not until after WWII that the label began recording contemporary jazz. Through the advice of talent scout Ike Quebec, the label began recording artists such as Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey and Horace Silver.

© Blue Note Records

Blue Note Records co-founder Francis Wolff, in a photograph by Rudy Van Gelder, taken with Wolff’s camera at Art Blakey’s March 6, 1960 “The Big Beat” session

…..Until it was sold to Liberty records in the mid-60s, Blue Note was the place to hear contemporary jazz in an almost purist setting. Unlike a notorious bottom of the deck dealer like Savoy Records, whose owner Herman Lubinsky was universally despised, Lion and Wolff treated their artists fairly and with respect. In an era when the big “money guys” in jazz were white stars like George Shearing, Stan Getz and Dave Brubeck, Blue Note almost exclusively recorded Black artists. The label paid for rehearsals and encouraged session leaders to bring original material to their recording dates. Blue Note would not release sessions they thought inferior (though they would pay the musicians a session fee). When musicians sought to borrow money from the label, they would instead arrange a session, pay the musicians and store the recording away for a future release. When these sessions started to become available in the early 80’s through the Japanese Toshiba label, fans were amazed at the quality of these “rejected” sessions.

…..Prestige Records was a somewhat shaggier outfit. Its founder, Bob Weinstock, was also initially a fan of classic jazz. He began as a teenage record dealer renting space inside the Jazz Record Center on West 47th Street and selling mail order through ads placed in the Record Changer magazine. He hung out at the Royal Roost, a former chicken restaurant turned jazz club located at 1800 Broadway in Manhattan. With jazz DJ Symphony Sid Torin booking acts, the Roost became the epicenter of the new jazz on the scene, hence it’s nickname “the Metropolitan Bopera House.” Weinstock, ever the entrepreneur, realized that many of the acts presented at the Roost were just too far out to attract the interest of mainstream labels, so he got into the recording business. Originally calling his label New Jazz Records, his first recordings were with the most far-out guy on the scene, the blind pianist Lennie Tristano.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Bob Weinstock in 1961

…..Compared to Blue Note, Prestige recorded a wider range of music, including folk, blues, “ethnic music” and non-categorizable like Moondog (its jazz roster was similar to Blue Note – in fact, musicians like Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, Miles Davis and John Coltrane recorded for both labels). What differed was the label’s approach to recording. With rare exceptions, Prestige labels were done without a rehearsal, Weinstock claiming that it made for a more spontaneous atmosphere. Sessions were created on the spot, made up of standards and perhaps a tune based on blues changes written on the fly.

…..Both labels were attracted to Van Gelder’s studios for similar reasons. The cost of recording at Van Gelder was considerably cheaper than New York studios; Van Gelder had a rather low overhead working initially out of his parents’ home and, later, at his own property in Englewood Cliffs, purchased just before a corporate boom on Sylvan Avenue.

…..Although the Van Gelder studios did record classical music for Vox and did a significant amount of pop music for C.T.I. Records in the 70’s, it was primarily a jazz studio. As a fan and a teenage player, he knew how the instruments functioned in a jazz ensemble and what they should sound like. His particular accomplishment was in his accurate rendering of the sound of a jazz piano and of the drum kit.

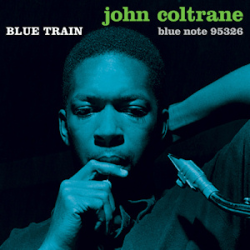

…..No better example of his work with recording jazz piano and the modern drum kit was that with the John Coltrane Quartet and Quintet. Coltrane, of course, was no stranger to either of Van Gelder’s two studios. He recorded consistently as a sideman and a leader at the Friday sessions reserved for the Prestige label. The sessions ranged from standard issue hard bop to the magnificent sessions the Miles Davis Quintet recorded to fulfill contractual obligations to allow him to record with Columbia Records – Miles treated the sessions almost like a night club date and called off tunes from the band’s book without a second take.

…..And, of course, there was Coltrane’s session for Blue Note, Blue Train. The record was made during Coltrane’s residency as a member of the Thelonious Monk Quartet at the 5 Spot Café, a period of breakthrough for the saxophonist. Coltrane brought four originals and a standard to the session. Van Gelder captures the ensemble magnificently, from the triple horn front line to Kenny Drew’s lucid piano solos. It is no wonder that when Coltrane was signed to Impulse! Records a few years later that he said, “Let’s use Rudy!” when label boss Bob Thiele asked about his choice of a recording studio.

…..The bulk of Coltrane’s recordings for Impulse! were done at Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio. The great achievement of Van Gelder’s work with Coltrane is the sound design that is created for the quartet. This was a group, especially when Eric Dolphy augmented the ensemble on his range of instruments, which often played a single tune for well over an hour. In addition to the group’s stamina on the bandstand, it played with such fervor to cause some patrons to get out of their chairs and raise their hands up towards the bandstand, as if they were at a Black Pentecostal service.

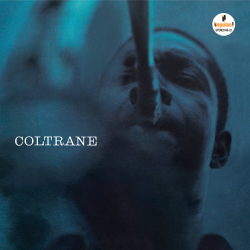

…..Van Gelder managed to balance Coltrane’s acoustic machine, bringing out the musicality and nuance of Elvin Jones’ radical approach to drumming, McCoy Tyner’s solid and melodic accompaniment, and Jimmy Garrison’s earthy and straight forward bass (which always seemed to be mixed low as to be an underlying presence). A good example of Van Gelder’s craft is on the album simply titled Coltrane (Impulse! AS-21). This album marks the first full recording of the Classic Quartet when Jimmy Garrison joins this working unit. In contrast to the recording strategies of the smaller labels, Coltrane is recorded in four separate sessions between April through June of 1962. Impulse! was a subsidiary label of ABC Records and allowed more studio time to complete albums – Prestige and Blue Note both insisted on recording an album in one day in two three-hour sessions – the musician union’s minimum time allowed for recording an LP.

…..The highlight of the album is the 14-minute reconstruction of the standard “Out of This World” into a modal workout much in the manner of “My Favorite Things.” This extended performance is a good place to hear how Van Gelder created portraits of performance. Overall, there is great presence on the recording – this was even evident as a 15-year-old playing this LP on a very cheap stereo. I often danced to this recording by myself in my teenaged basement lair.

…..There is a minority opinion that considers this album the great recording of the Classic Quartet. Certainly, the album has variety and range. The other classic on the LP is Coltrane’s definitive recording of Mal Waldon’s “Soul Eyes.” There is also a whimsical version of Frank Loesser’s “The Inch Worm” played as a jazz waltz. This sort of playfulness vanishes from Coltrane’s music as it becomes increasingly austere and abstract in the last few years of his life. The album remains a great introduction to the mature phase of Coltrane’s career for newcomers to jazz.

…..The film critic and jazz connoisseur Richard Brody offered an incisive comment about the role of this soft spoken and modest sound engineer: “Van Gelder is something like a crucial cinematographer, like the Raoul Coutard of modern jazz, whose own audacity fused with that of the artists at work to render the music with a sense of physical impact and deep psychological resonance. He approached technique with an artistic sensibility, even in its very inner-driven practicalities.”

Brian Mcmillen, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Red Garland, 1978

…..The case for “deep psychological resonance” can be made in Van Gelder’s documentation of pianist Red Garland, who played a crucial role in Miles Davis’s first quintet. In addition to being the group’s pianist, his unusually deep knowledge of the standards repertoire added obscurities to the band’s book that often became jazz standards themselves, such as “If I Were a Bell” from the musical Guys and Dolls. Less-known about Garland is that he recommended both Philly Joe Jones and John Coltrane to Davis to help round out the quintet.

…..Ethan Iverson, the former pianist in the Bad Plus, stated in his Do The Math blog that Red Garland’s music is “always dusky, always in the cracks, always a bit sad, always a bit cheerful. Always ringing the changes and always playing the blues.”

…..Although his fellow jazz pianists revere Garland, his reputation was suspect amongst the jazz beaus when I was a young fan in the early 70’s. That period was filled with exciting young players like Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock who wrote their own material, led of-the-moment ensembles, and were often comfortable playing the new generation of electronic keyboards. Garland, to many of us, seemed terribly corny, “a cocktail player” as a slightly older friend labeled him. (The shabby jackets he wore on his cover shoots didn’t help either). It was not until I got older that I could appreciate him. I remember confiding my love of Garland to the late Larry Fagin, an older poet who was also a deeply opinionated jazz fan. Instead of the expected putdown, Fagin said in a hushed voice, “I do, too. Even if we’re not supposed to like him!”

…..Van Gelder recorded almost all of Garland’s output from 1956 to his departure to his hometown of Dallas in ‘62, where he took care of an aging mother and supported himself on the royalties from his 20-plus solo albums (which sold like crazy in Japan), and the occasional club gig.

…..You don’t buy a Garland album to hear a virtuoso improviser like Bud Powell or an excursion on a wobbly musical rail like Cecil Taylor or Thelonious Monk. Van Gelder’s sound design brings out the deeply personal landscape in his playing—it can function as “make out” music, background music for an intimate hipster dinner party, or just something to play as you read the New York Review of Books and sip a glass of wine. An album I’ve always been partial to is a date recorded December 11, 1959, that features Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis on a few tracks and was issued on Prestige’s Moodsville label, which was set up to cash in on the “easy listening” craze of the late 50’s/early 60’s. Yes, this album (known as Moodsville Vol. 1) is very close to the dread “cocktail piano”—the music is more languid than the already leisurely-paced Garland. This may be a perverse and idiosyncratic choice on my part but what pulls me in is the sheer dreaminess of the project – the songs have no pauses and just flow into each other with Lockjaw’s beyond gruff tenor seemingly the one thing that keeps this group from driving off the highway in a full junkie’s nod. I know it is a bad pun, but the record has a true narcotic effect on the listener. Too bad the album is so brief at 30-plus minutes. It should really go on for hours like one of Stockhausen’s late pieces, a musical humidifier extruding standards and the blues along with the mist..

.

4.

.

…..I worked part-time during college at a store called Jazz Etc. It was a specialty record shop that sold nothing but jazz and had a finely curated collection that focused on rarities, out of print items and imports from Europe and Japan. The major domo of the inventory was storeowner Bob Porter, a freelance producer who specialized in soul jazz. He had recorded about 90 albums in Van Gelder’s studio, mostly for the Prestige label.

…..Bob was recording master soul tenor saxophonist Rusty Bryant for the newly revived Savoy label and invited me to watch the proceedings. As I was walking my way up 7th Avenue in midtown Manhattan, I was on shpilkes with anticipation – the studio was the legendary A&R recording studio owned by the equally legendary producer Phil Ramone. This was Tom Dowd’s studio of choice for those great Atlantic soul records. Sinatra! Streisand! Dylan! They all recorded here.

…..When I got there, I was underwhelmed by the plain functionality of the place. I’m not sure what I was expecting—maybe something that materialized all that music floating in my head. A bored receptionist led me in, and I sat in a cramped waiting room where I watched the tedious work of putting together an album. (I did get to shake Bernard Purdie’s hand).

…..Van Gelder’s two studio locations were both created by architects to specifically meet the needs of a working studio. The famous Hackensack “studio” was the home of Van Gelder’s parents – Rudy Van Gelder lived there as an adult up until the time he married his first wife. When his parents decided to build a home on a lot on 25 Prospect Ave, they immediately acceded to the wishes of their sound-hungry son by having the architect make the living room ceiling higher than the rest of the house and by adding a control room with a double glass window next to the living room. As Van Gelder told Marc Myers: “I wanted to perfect the techniques of contemporary music recording.”

…..The U-shaped home is what is called a “California-style” house, obviously typical on the West Coast but startlingly modern in suburban New Jersey. Van Gelder was fond enough of the family manse that an image of the home was stamped onto the master discs that he produced; the great art director Paul Bacon designed the image. The designer of this house was a Paterson-based architect named Sidney Schenker, who designed restaurants in downtown Paterson as well as movie theaters, including the still-intact Allwood Cinema 6 in Clifton, NJ.

…..Although the Hackensack studio has a legendary status among jazz fans, the studio was only used for about six years. That studio was, after all, his parents’ living room, so it lacked the space to record large ensembles. And, with an enormously busy schedule generated by the explosion in record sales which resulted from the introduction of the long-playing album that was soon followed by the debut of stereo, Van Gelder began searching for a property to build a brand-new studio. The lot he purchased on Sylvan Avenue was just minutes from the George Washington Bridge, making it closer to both Manhattan-based record producers and the musicians who would play in the studio.

…..It was Van Gelder’s first wife, Elva, who had seen an exhibit on Frank Lloyd Wright, which featured a reproduction of one of Wright’s Usonian Homes. The famed architect had intended it to be a home that was affordable to middle-class families. Ms. Van Gelder sought out the designers of the model home and, after a discussion of Wrightian architectural principles, the Van Gelder’s commissioned David Henken to design and build the new studio. Henken, an engineer by training who apprenticed with Wright, was both a designer and a founder of Usonia, a planned community in Mt. Pleasant, New York created in 1947 by a group of friends which not only abided by Wright’s vision of community, but had three of its 47 homes designed by Wright, who additionally signed off on the remaining homes which were designed by his associates.

…..David Henken created a building that had enough of a resemblance to a chapel to cause the critic Ira Gitler to write in the liner notes to saxophonist Booker Ervin’s Space Book LP: “In the high-domed, wooden-beamed, brick-tiled, spare modernity of Rudy Van Gelder’s studio, one can get a feeling akin to religion, a nonsectarian, nonorganized religion temple of music in which the sound and the spirit can seemingly soar unimpeded.” Gitler clarified his comments in a tribute in Jazz Times: “Rudy didn’t say anything at the time but in 2000 he straightened me out. The wooden beams are in the roof,” he explained, “and the walls are not tiles but masonry.” The most striking feature of the studio was the 39-foot ceiling and the austere masonry walls that were the same white color inside and outside the building. The tree-lined driveway is not easy to find – something I learned as a kid when I and some other jazz loving friends went on a search for the studio (with no success).

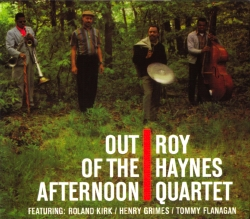

…..Although the studio is a few hundred feet from the Palisades Interstate Park and Parkway and a block from Palisades Avenue which leads down to Englewood Boat Basin, a major recreation area on the Hudson, I’ve only found one item that links Van Gelder’s sound chapel to the outside environs. It is the cover of Roy Haynes’s 1962 date for Impulse!, Out of the Afternoon. Haynes’s quartet is standing in a wooded area, the low sartorial standards and clash of wardrobe among the quartet (save for Haynes who was often on Playboy’s best dressed list). When I interviewed the drummer for NJPAC program notes, I asked him about that cover: “Oh yeah, the photographer took us into the park outside Rudy’s place, found a clearing & took some photos after the session. That’s about it. I remember, though, the music that we made that day is within me to this day.”

.

5.

.

…..The great era of classic jazz sessions at Van Gelder Studios came to an end beginning in the late 60’s. Blue Note and Prestige were purchased by larger entities that were little interested in acoustic jazz and shifted much of their operations to the West Coast. Verve and Savoy ceased recording jazz altogether, and Impulse! shifted their operations to Los Angeles before closing up shop in the late 70’s.

…..Van Gelder’s main client in the 1970’s was CTI Records. Founded by former Impulse! and Verve producer Creed Taylor as a subsidiary of A&M records, the label went independent and became one of the great commercial success stories in jazz history.

…..Taylor came upon the strategy of the jazz label as a first-class operation. He signed up musicians whose commercial potential hadn’t been fully realized- players like George Benson, Freddie Hubbard, Hubert Laws and Stanley Turrentine. He hired Don Sebesky to arrange for large orchestras and secured the best session musicians in New York City. The albums were gorgeously packaged – almost all were gatefold covers and the great color photographer Pete Turner created a series of startling images that caught the attention of anyone browsing in the jazz bins of a record store.

…..Taylor chose Van Gelder Studios to record and in the heyday of his label he had exclusive use of the studio. Many of the CTI records really sold numbers like pop albums and made performers like Hubbard and Laws names that more sophisticated pop fans recognized. You didn’t even have to have much of a recording track record to benefit from the CTI touch. Grover Washington, Jr., a solid soul-jazz saxophonist who earned his keep in Charles Earland’s band, was pressed into service when Hank Crawford failed to show up for his own session. Taylor did not want to waste a room full of studio musicians who would be paid whether they played or not, so Washington, Jr. was quickly deputized to be the featured soloist, and the success of this date launched an enormously successful career that eventually landed him on the pop charts.

…..CTI, however, is something of a schanda to straight-ahead jazz fans. Folks who bought Freddie Hubbard’s classic Blue Note dates mostly disdained his CTI albums with their rock-ish beats and lush arrangements. I think that the serious jazz coterie missed the point – with very few exceptions, CTI records were made for the casual jazz listener who heard something he liked on one of the now extinct commercial jazz radio stations and picked up a copy at the local record shop, where CTI records were usually on full display. The sophisticated packaging suggested to the purchaser that he (and it really was often a “he”) had made an educated decision to buy the album. You could plop a CTI record onto a turntable at a party and be assured that no one would yell “Turn that OFF!” which was the experience of many a Coltrane or Ornette Coleman fan.

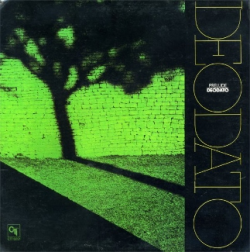

The 1972 CTI album Prelude by Eumir Deodato

…..Van Gelder, for his part, was pleased with his work for CTI. In addition to a packed recording schedule, Van Gelder had a chance to work with full-scale orchestras (usually including a string section), electric instruments and vocalists. The biggest hit that Van Gelder ever engineered was by the Brazilian arranger/composer Eumir Deodato. Going under his surname, he recorded a disco-y version of Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, known at large from Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 blockbuster film, 2001: A Space Odyssey. The single rose to #2 on the charts and the album, Prelude, where the single appeared on, also went “Gold.”

…..These CTI records, especially the recordings from the early years of the label, still sound fresh and the best of them are far more listenable than detractors from 45 years ago would admit. The records are free from gimmicks and, if you take them on their own terms, are well-made examples of pop jazz.

…..The last phase of Van Gelder’s career as a sound engineer involved remastering the many albums recorded at his studio. When the compact disc was introduced in the early 80’s as a new listening medium, many back catalog items suffered from poor remastering. Sometimes, second generation masters were used as the remastering source. And, in the main, many engineers were still learning the intricacies of digital recording, which was introduced only a few years ahead of the CD.

…..It was the Japanese Toshiba-EMI label, which commissioned Van Gelder to remaster 250 classic Blue Note albums, and it was the newly-revived Blue Note label that made Van Gelder’s name a selling point. The label managers created “RVG Editions” and promised listeners a listening experience comparable to the first pressings of the original LP. Following the example of Blue Note, Prestige records began their own RVG Editions, with Van Gelder tackling the sessions he did at his studio as well as other sessions recorded elsewhere that needed a bit of his magic.

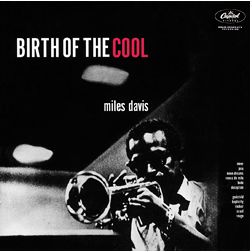

…..The great example of Rudy Van Gelder’s skill as a remastering engineer is his work on an album he did not initially record – Miles Davis’s Birth of The Cool. This was one of the first jazz albums I bought as a teenager – I think it was part of a short-lived jazz reissue program Capitol records had in the early 70’s. I loved the music, still do, but was aware of the sonic limitations of the recordings as compared to contemporary music I was also listening to. I long-assumed that this was just the limits of music recorded in the pre-Hi-Fi era. What I was actually listening to was the indifference of a label that had gotten out of the jazz business long ago and grew fat on the Beatles and the other rock acts in their stable.

…..Van Gelder’s work on this record is amazing. There is now depth to the recording, as well as the fully empowered trumpet of Miles. As Van Gelder told Ira Gitler:” I was able to go back to the original masters, tune by tune, using the best available technology, and combine it with the memory of my hearing of the 78s when they first came out. I didn’t treat them as an album but as a series of singles. With Miles in mind, I tried to make them sound the way he would have liked to have heard them.”

…..Van Gelder continued to record contemporary jazz until the end of his life. Although the very low financial margins that jazz operates under has forced many musicians to turn their basements or living rooms into recording studios with the help of a laptop, some good mics and recording software, the lure of recording in the Van Gelder studios is something many young musicians dream about. The last session that Van Gelder recoded at the studio was June 20, 2016 – less than two months before he died at 91. It was a trio led by Jimmy Cobb – a workman-like drummer who is the last surviving member of the ensemble that recorded Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue.

…..What will become of the studio now that the master is no longer at the mixing board? The great Manhattan studios have mostly shut down – a combination of high rents and declining bookings for studio time. Most live session work has long moved out to Los Angeles, where movie scores are recorded with full orchestras. Some musicians have moved to Nashville – where they still record music the old-fashioned way, i.e. with actual instruments and not electronic instrumentation. And some musicians take their conservatory training and head down to Orlando, Florida, where Disneyland is one of the largest employers of musicians in the country. It is a very great distance from the 40’s, when the musicians union launched two recording bans over a dispute regarding the playing of records on the airwaves.

…..Rudy van Gelder outlived his two wives and had no children. In his will, he gave the studio and his home to his long-time assistant Maureen Sickler. She wants to preserve the studio and has been working with the Bergen County Historical Society to obtain landmark status for the building based on the music recorded there, the Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired architecture, and the story of the lives of the many Black musicians who literally made musical history there. “My job is to make sure the building is preserved so that people can learn about what Rudy accomplished and that musicians can make music in it for my lifetime and after,” she wrote to a reporter for the North Jersey News in an email. “I don’t have any concrete plans yet, but I hope to involve the musicians, producers and fans who were such an important part of his life.”

…..Despite Ms. Sickler’s vision of the Van Gelder Studio as a museum, she and her husband, trumpeter/arranger Don Sickler, continue to record at Van Gelder’s cathedral of sound using the same equipment that the Master purchased and deployed. Moslems are commanded to make the hajj to Mecca. Jews dream of praying at the Western Wall, and jazz musicians hope that some sympathetic magic rubs off the walls of the walls of Rudy’s place – which is why the Sicklers continue to book studio time.

.

CODA: A Visit to the Van Gelder Studio

.

…..I had already sent off my essay to Jerry Jazz Musician aware of an upcoming deadline and was a bit frustrated that I was unable to contact Maureen and Don Sickler who own and manage the Van Gelder studio. The studio’s minimal website offered no help and the phone number to the studio was not in service. I did manage to obtain what I was assured was a functioning email, but received no response until the day after emailing my article. I received a friendly response from Don Sickler, who indicated he was up for a visit. I called him on the phone number he provided in his message, and we set up a date on an October Sunday afternoon, which happened to fall in the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; so instead of visiting a temple of worship, I’d be visiting a temple of sound.

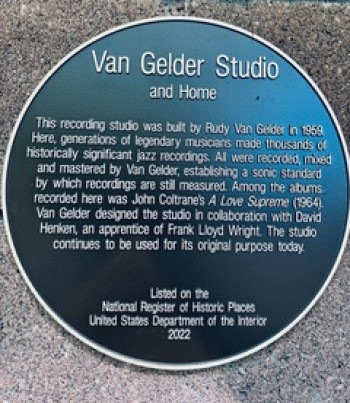

…..As Don warned me, Uber drivers have a hard time finding the studio. After attempting to drop me off at a bank parking lot, Nikolai spotted the small driveway leading to what I hoped was the studio. I wasn’t quite sure where I was until saw the National Register of Historic Places plaque affixed to the building. Finding the doorbell, I was soon welcomed in by Don Sickler and introduced to his wife Maureen, who has engineered all the sessions at the studio since Van Gelder’s death. They are a warm, simpatico couple who are also people with a mission – to continue the legacy of the studio. “We’re one of the few studios operating in the New York City area,” Don noted, “and many jazz musicians who used studios like ours now set up studios in their homes to save on recording costs.”

…..As functional as the outside of the building seems, the interior is spare and beautiful and fully follows modernist architect Louis Sullivan’s dictum: “Form follows function.” Don, a trumpeter, arranger and music publisher, noted what makes the studio so special: “The studio has incredible acoustics. The formula that Rudy devised in designing this place was no paint, raw stone and raw wood. The room not only has a natural sound, but a natural decay of the sound.” To prove this point, he whupped out his trumpet and played a few notes then stated: “What Rudy was after was getting the natural sound of the musician. Trumpeters, in particular, wanted to record here because of the way Rudy captured their sound.” Being that kind of jazz nerd, I had to ask what kind of wood was used to create the unique ceiling of the studio. Maureen Sickler was quick to answer: “The beams are Douglas Fir. The decking is Cedar, and everything else in the studio is Philippine Mahogany.”

…..I was ushered into the engineering room, the “holiest of holies” in this acoustic temple. In the pre-digital era, no one was allowed into the room other than Van Gelder. In fact, some of those sanctions still exist: I was not allowed to take photos of the sound console.

…..I asked Maureen how she came to work for Van Gelder. “In 1986, Rudy was asked to record a live date of the pianist Tommy Flanagan,” she responded. “Rudy wouldn’t do the date unless he had an assistant. I was familiar with Rudy and the studio through Don’s work here, so I was recruited to work on that session. When digital came in, I became an assistant engineer at the studio. Rudy couldn’t type and the new equipment used keyboards, so I was inputting commands. From the start, Rudy always wanted to have the latest in recording technology, so I learned all the new equipment when they came into the studio. I would also set up the microphones for sessions, but only Rudy could operate the console.” After Van Gelder’s death, it was musicians like Ron Carter who urged Maureen to keep the studio functioning and to take over the engineering duties, arguing that her years of work with Van Gelder made her the logical choice.

…..While talking with the Sicklers about Rudy Van Gelder, a portrait emerges of a man with a mission. His life work, in a way, refutes Eric Dolphy’s famous comment to a Dutch interviewer: “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone in the air, you can never capture it again.” When I asked Don if Rudy went out to hear live music, he said, “Rudy often did as he was interested in hearing how a musician sounded in a live setting in order to capture that sound in the studio.” When I asked Maureen what kind of boss Van Gelder was, it was Don who answered: “Rudy was not a ‘boss’. Unlike most recording studios, he never had any kind of assistant until Maureen began her work. It was more of a father-daughter relationship – Rudy never had children of his own.”

…..When I asked about the future of the studio, they indicated that they did get National Landmark status in 1922 but have stalled on the plans for creating a non-profit that was mentioned in several newspaper articles appearing around the time of Van Gelder’s death. Maintaining a working studio in the New York City area is not an easy gig. One issue is overhead: the studio is 60 years old and despite its solid construction, there are always maintenance issues. Another bedevilment is that the studio sits on one acre of very valuable property; its neighbors on Sylvan Avenue include Unilever, LG Electronics and NBC. “Rudy acquired this property just before corporate development on Sylvan Avenue,” noted Don, “and now the studio has a hefty property tax to deal with.” Nonetheless, Don and Maureen batted down my suggestions of university affiliations or training a new generation of sound engineers. Maureen, who was reserved throughout our conversation, was very emphatic when she stated: “I think it’s important that musician record here and keep this an active studio.” Don seconded his wife, noting: “It’s a humbling experience for musicians to record here. It’s the quality of the room and the presence of the greats who played here. Also, you don’t have to work hard here to be heard – you can play softly, and it comes out clear and large in the recording.”

…..We left the recording room and headed back into the studio space. The piano tuner was due soon, so it was time for me to head home. Don noted the studio Steinway was brought in by Rudy from the old studio located in his parents’ Hackensack home. “We tune it after every session,” Don said. “This is the piano that Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans recorded on.” And behind the piano was the Hammond organ that virtually every organist of the soul-jazz heyday recorded on – although it is a Hammond C-3 Model rather than the legendary B-3 so associated with the organists of that era. I picked up a copy of the New York City Jazz Record tabloid from a stack near the door as reading matter for my bus ride back to Hoboken. “The people from the paper are kind enough to drop them off here,” Don said. “The musicians read it during the breaks. I feel bad that we don’t take out an advertisement in the paper.” I asked if the studio ever advertises its services. “No, we never do that,” he replied. “Musicians know where to reach us.”

.

.

___

.

.

Joel Lewis’s Well You Needn’t, a book of poetry and memoirs about 55+ plus years of listening to jazz, will be published by Hanging Loose this December. He has written about all sorts of music and spent a decade writing program notes for NJPAC in Newark, New Jersey, getting to interview many of his musical heroes. He resides in Hoboken, New Jersey.

.

.

.

___

.

.

Photos taken by Joel Lewis during his visit to Van Gelder’s studio

.

.

The studio

.

Another view of the studio

.

The studio ceiling

.

The disk machine

.

Don Sickler with the disk machine

.

The Hammond C-3 organ

.

The plaque commemorating the studio as a National Historic Place

.

.

___

.

.

Rudy Van Gelder engineered countless tracks. You can click here to view a list of albums he was credited for having worked on.

Here are three that were discussed in the essay:

.

“Out of This World” by John Coltrane (with McCoy Tyner (piano); Jimmy Garrison (bass); and Elvin Jones (drums) [Universal Music Group]

.

John Coltrane, “Soul Eyes” (with Tyner, Garrison, Jones) [Universal Music Group]

.

Red Garland plays “Stella by Starlight” with Sam Jones (bass) and Art Taylor (drums). [The Orchard Enterprises]

.

.

___

.

.

Sources

Brody, Richard. “Postscript: Rudy Van Gelder (1924-2016): Modern Jazz’s listener of Genius.” New Yorker, August 26, 1918

Enslinn, John. “The Van Gelder Studio: Peak inside the studio where classic jazz happened.” North Jersey News, February 21, 2018

Gitler, Ira. From liner notes, Booker Ervin “The Space Book.” Prestige 1965

Gitler, Ira, “In Van Gelder’s Studio.” Jazz Times, April 2001

Iverson, Ethan. “Red’s Bells.” Do The M@th blog (ethaniverson.com)

Myers, Mark. “Interview with Rudy Van Gelder.” Jazz Wax.com. February 13, 2012

MacLeod, David “Making the scene in New Jersey from Edison to Springsteen and Beyond.” Rutgers University Press and Beyond, 2020

.

I conducted a background interview with the late Bob Porter for this story. Bob had produced 90 albums at the Van Gelder Studio and spoke at Rudy Van Gelder’s funeral. While in college I worked with Bob at his record shop Jazz, Etc. located in my home town. He often spoke of the Van Gelder studio and its master engineer.

In my revising of this essay (which was initially begun at the time of Van Gelder’s death), I came across the RVG Legacy site (rvglegacy.org), which was put together and is maintained by Richard Capeless, the author, developer, and designer of the site. Capeless, a college math instructor, audio buff and vinyl maven, has much information about the studio, with a lot of nuts-and-bolts info about the equipment that Van Gelder employed. There is also a sessionography of recordings made in the classic period of the studio. Capeless told me he has yet to tackle the CTI and beyond period, given that the site is a labor of love and someone has to teach kids college level math in the upper reaches of the Hudson.

-Joel Lewis

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read Joel Lewis’ essay, “Well You Needn’t – My Life as a Jazz Fan”

Click here to read “Gone Guy: Jazz’s Unsung Dodo Marmarosa,” by Michael Zimecki

Click here to read “Like a Girl Saying Yes: The Sound of Bix” – an essay by Malcolm McCollum

.

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here to read “A Collection of Jazz Poetry – Spring/Summer, 2024 Edition”

Click here to read “Not From Around Here,” Jeff Dingler’s winning story in the 66th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

Well-researched, well-written and a pleasure to read, thank you!