.

.

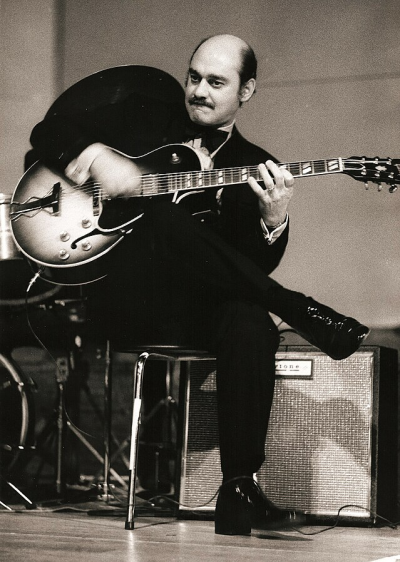

On the 30th anniversary of the guitarist Joe Pass’ death, Kenneth Parsons reminds readers of his brilliant career…

.

.

___

.

.

Hans Bernhard (Schnobby), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Joe Pass; 1974

.

.

Remembering Joe Pass: Versatile Jazz Guitar Virtuoso

by Kenneth Parsons

.

….. Joseph Anthony Jacobi Passalaqua was born in Brunswick, New Jersey, on January 13, 1929, the son of Mariano Passalaqua, a native Sicilian. The family moved to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where Mariano took a job in a steel mill. An elementary school teacher told the father his son Joe showed a talent for music. Mariano did not want his children – Joe was the oldest of five sons and one daughter – to grow up to work in a steel mill or a coal mine. So he bought his nine-year-old son a $17.00 Harmony acoustic guitar and a lesson book.

….. Two hours before going to school, two hours before dinner, and four hours each night Joe practiced the guitar, learning to read music, making chords, and practicing scales. His father told him he needed to learn some songs of his native Sicily. Joe learned to play these songs as soon as his father told his friends, “My son plays guitar,” when they relaxed enjoying their wine and cards on weekends.

….. The young boy took a guitar lesson on Sundays, but he had to play songs – he couldn’t play scales or exercises when he was called to play for Mariano and his friends. His father encouraged him to “fill it up,” to improvise around the melody and avoid silent spots and rests. Joe had to learn the fundamentals of music fast, as his father firmly commanded him to do.

….. By age 14, he was out playing professionally at parties and dances, playing in trios or quartets in which he was the soloist. A local musical instrument store owner played jazz music records in his place of business. Joe heard Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, but when he heard Charlie Parker play he was floored. He didn’t try to imitate other guitar players, even Charlie or Django, but it was horn players Joe tried to make his phrases sound like.

….. When he was 20 Joe went to New York City, but like many young musicians there, he began using heroin less than a year after he arrived. For the next decade and a half Joe would have a problem with drugs. He traveled to different cities to play music and to get high: including New Orleans, Fort Worth, Los Vegas, and Los Angeles, hotspots for jazz.

….. He told Rolling Stone his priorities at this time were getting high, playing jazz, and girls – in that order. Unfortunately, the first priority took up all his energy, he said. He was arrested in 1954 for drug possession and was sent to a U.S. Public Health Service Hospital for four years. After being released he was in-and-out of jails for drug-related offenses.

….. In 1960 he entered the Synanon, Santa Monica clinic for drug rehabilitation and stayed for two-and-a-half years. One of the financial supporters of Synanon was also the owner of World Pacific Records, and he suggested that the jazz musicians in the program make a record. The record was released to positive critical acclaim, especially for Joe, who played an uncustomary Fender solid-body Jaguar guitar for the session. Most jazz guitarists would play hollow body guitars.

….. Downbeat magazine praised the guitarist’s performance on the recording, and he was awarded their New Star Award in 1963. After he left Synanon, he recorded with several Pacific Jazz artists, and was in demand in the studio and on the stage. He settled in Los Angeles doing television, studio, and nightclub gigs.

….. In 1963 Pacific Jazz released the album Catch Me, and in 1964 the live Joy Spring, and For Django, which rhythm guitarist John Pisano played on, and who would frequently accompany Joe throughout his career. In 1965 Joe toured with the pianist George Shearing, and the demand for his performances and studio work continued to grow. In 1966 he released what critics called a rather sentimental work Simplicity, with the record’s title song written by Joe.

…..Curiously, his next recording in 1967 was titled Stones Jazz, and was mostly made up of guitar covers of songs by the Rolling Stones. Was this his attempt at doing what Wes Montgomery did – to take a major popular radio hit and create a guitar version of the song? Maybe, but the record did not do well on the Billboard Jazz or Popular Music charts.

…..Over the years, Joe played on records with Julie London, Chet Baker, Carmen McRae and others. He also worked as a sideman for Frank Sinatra, Della Reese, Steve Allen, and Johnny Mathis, and played dates on the Merv Griffin Show when filling in for fellow guitarist Herb Ellis.

…..In 1971 he and Ellis became a guitar duo, recording a studio album together in 1972 with Ray Brown on bass, and Jake Hanna on drums – the initial release on the Concord Jazz label. The following year the same quartet played the Concord Jazz Festival. and this recording was later released as Seven Come Eleven. The album’s title track was the classic 1940 Benny Goodman and Charlie Christian composition.

…..Joe toured Australia with Benny Goodman, and when he returned the impresario and Verve Records founder Norman Granz signed him to his new label, Pablo Records. In November and December 1973 Joe recorded his first solo record, Virtuoso, an album of 11 jazz standards and one Pass original, “Blues for Alican,” that would come to be recognized as a jazz masterpiece.

…..Virtuoso was recorded with Pass playing a Gibson ES-175 hollow body guitar miced but unamplified. The record opened with Joe’s interpretation of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day” and closed with Jerome Kern’s “The Song is You.” Joe played the melody, chords, and bass lines simultaneously, putting his personal signature on each tune, sometimes sounding like more than one guitar playing. .Jazz guitarists and jazz aficionados should not go through this life without a close listening to Joe’s miraculous performance on Virtuoso.

…..Joe did not rest on his laurels, joining Oscar Peterson on piano and Nils-Henning Orsed Pedersen on bass in a group named The Trio. They won the Grammy Award for Best Jazz Performance by a Group in 1975 for their self-titled record, which was also released by Pablo. This group continued to perform together on numerous occasions in the 1970’s and 80’s.

…..The list of jazz artists Joe played with would grow to include Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, and Ella Fitzgerald, with whom he made six albums on Pablo Records. The consensus in the jazz world was that Joe Pass could play solo or accompany anyone, and he could play anything the artist wanted to play. If a jazz musician needed a guitarist, Joe was a first-call on many a musician’s list.

…..Though the sound of guitar went through many changes with wah-wah pedals, phase shifters, delays, choruses, and synthesizers, etc., etc., during the 60’s to the 90’s, Joe stuck with an archtop guitar – most often a Gibson ES-175 – and a Polytone amp.

…..There’s the story of Joe doing a Blindfold Test with a Downbeat magazine writer to see if he could identify the guitar player, and what he was using or doing on his instrument to get his sound, and the test giver put on a Jimi Hendrix record. Joe responded by telling the test giver to “turn that s**t off. That’s not even music.” This was Joe Pass the jazz purist.

…..In early 1990, the Adelaide Festival of Arts in Australia featured a program “Aspects of the Guitar, Four Guitars.” The four guitarists were: John Williams (classical), Paco Pena (flamenco), Leo Kottke (acoustic steel-string) and Joe Pass (electric jazz). There were two performances at different venues, and each guitarist performed for a half-hour during both programs. The following day there was a discussion forum with each performer present on stage with his instrument. This was Joe Pass the educator. .He had authored more than a dozen instruction and method books and several videos for students to learn about his style of playing guitar, and he often engaged in discussions publicly and privately with other musicians about subjects such as improvisation and harmonization. He answered students’ and seasoned musicians’ questions humbly and respectfully, without arrogance or condescension.

…..In 1992, Joe was diagnosed with liver cancer. Despite the illness, and since he was responding well to treatment, he agreed to go on tour with Pepe Romero, Paco Pena, and Leo Kottke in a program named “Guitar Summit.” Again, the guitarists performed and later met in a forum with those who attended the concert to discuss their approach and execution of their individual playing styles.

…..The “Guitar Summit” got off to a good start in late ‘93, but Joe’s condition suddenly began to worsen, and he had to leave the tour and returned to Los Angeles. His final recording, Joe Pass & Roy Clark Play Hank Williams, was released in early 1994 on Buster Ann Records, and Joe played his last gig on May 7, 1994 with John Pisano at a nightclub in Los Angeles. At the end of the show Joe tearfully told Pisano, “I can’t play anymore.” Pisano said it felt like a “knife in his heart.” Joe Pass died of liver cancer on May 23, 1994.

…..Solos, duos, trios, and quartets to orchestras, Joe Pass played them all on stage. His guitar work appeared on more than 70 albums in the fore-mentioned settings live and in the studio. When it came to jazz guitar he was the “Man of His Time.” Proclaimed by many as the best jazz guitarist since Wes Montgomery, Joe Pass was the most versatile of all the jazz guitar virtuosos in his 50-year playing career.

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

Kenneth Parsons has taught English in the U.S., China, Japan, and South Korea. His poems have appeared in many literary magazines, including Shi Kan, China’s official poetry monthly magazine. He has also published fiction and creative non-fiction on online publications such as Terror House and Drunk Monkeys. His novel Our Mad Brother Villon was published in 2015 by Little Feather Books, and his novel manuscript, Joyriding Through Toonsville, was runner-up in the Nicholas Schaffner Music in Literature Prize in June 202. I Am Your Wastrel, his crime fiction novel, has been contracted for release in the Fall of 2024 by Close to the Bone Books in North Hampton, England.

He is also an amateur guitarist with a passion for progressive rock and jazz fusion. His historical novel Boppin’ to the Blue Beat: Charlie Christian, the Pres of the Electric Guitar was published independently in July 2022 in the pen name of A.R. “Adam” Abernathy. Four articles about virtuoso guitarists appeared in Drunk Monkeys in 2021-2023. He lives in Goyang City – a suburb of Seoul – with his wife Song Seon Sook.

.

.

Listen to the 1977 recording of Joe Pass performing “Joy Spring” [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read “A Mountain Pass (In memory of Joe Pass)” – a poem by Bhuwan Thapaliya

.

Click here to read previous editions of The Sunday Poem

Click here to read “A Collection of Jazz Poetry – Winter, 2024 Edition”

Click here to read “Ballad,” Lúcia Leão’s winning story in the 65th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.