.

.

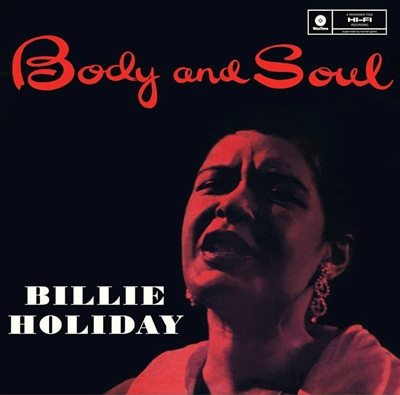

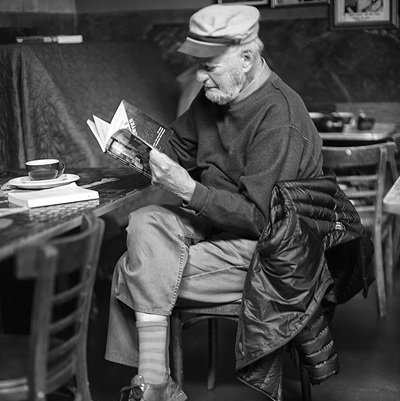

Neil Lanctot, author of Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution

.

___

..

The story of black professional baseball provides remarkable perspective on several major themes in modern African American history: the initial black response to segregation, the subsequent struggle to establish successful separate enterprises, and the later movement toward integration. Baseball functioned as a critical component in the separate economy catering to black consumers in the urban centers of the North and South. While most black businesses struggled to survive from year to year, professional baseball teams and leagues operated for decades, representing a major achievement in black enterprise and institution building.

Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution presents the extraordinary history of a great African American achievement, from its lowest ebb during the Depression, through its golden age and World War II, until its gradual disappearance during the early years of the civil rights era. Through his efforts, author Neil Lanctot has painstakingly reconstructed the institutional history of black professional baseball, and provides valuable insight into the changing attitudes of African Americans toward the need for separate institutions.#

Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution presents the extraordinary history of a great African American achievement, from its lowest ebb during the Depression, through its golden age and World War II, until its gradual disappearance during the early years of the civil rights era. Through his efforts, author Neil Lanctot has painstakingly reconstructed the institutional history of black professional baseball, and provides valuable insight into the changing attitudes of African Americans toward the need for separate institutions.#

Interview hosted on June 7, 2004 by Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

‘

___

.

A sampling of the critical acclaim for Negro League Baseball:

“Prodigiously researched and thoroughly unsentimental, Neil Lanctot’s history of organized black baseball from 1933 through the early 1960s provides an enormously important historical corrective to feel-good versions of baseball integration.” — New York Times

*

“Lanctot takes us beyond the ball field where the Paiges and Gibsons played in forced segregation, and into the commercial and social realities of baseball in black communities. . . . Lanctot offers a rich array of facts that history lovers can feast on.” — Washington Post

*

“This is a superb historical analysis of the Negro Leagues. . . . Lanctot provides, in my opinion, the most detailed and sophisticated examination of black baseball ever written.” –David K. Wiggins, author of Glory Bound: Black Athletes in White America

.

.

____

.

.

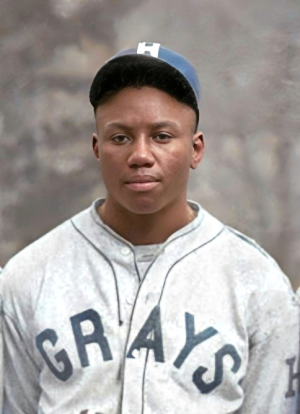

Harrison Studio, Public domain (colorized) via Wikimedia Commons

Negro League legend Josh Gibson of the Homestead Grays, 1931

“The Negro always should resist segregation in every form. He should never voluntarily accept and institutionalilze the status resulting from segregation except where sheer necessity compels him to do so — and then only under continued protest. Every separate institution undeniably tends to perpetuate our present status. The only separate minor institutions or organizations which we should build, or maintain and support, are those that serve our daily needs and those that are designed for the achievement of our major objective — demolishing of all racial barriers.”

– Ferdinand Morton, the Negro National League commissioner between 1935 – 1937

.

___

.

JJM Your book traces the national development of the black baseball business from its lowest ebb in the worst days of the Depression to its extinction during the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, focusing on three distinct phases; #1 being during the Depression, #2 during the World War II era, and #3 being irrelevance, the post-integration period of 1947 – 1960’s. What obstacles did you face in attempting to compile this history?

NL The biggest problem was the lack of sources. Because we don’t have many original source materials from the Negro Leagues, black newspapers are a major source of information for a topic like this. While some of the correspondence has survived — in particular that of the Newark Eagles — not much of the primary source information beyond that and what was reported in black newspapers has survived. So, I had to cobble this book together basically from reading multiple newspaper accounts from black newspapers in different cities, and augmenting that with the relatively few letters and correspondence still available — as well as information found in white newspapers and in court records.

JJM Your book took the path of looking at the Negro Leagues as a business enterprise rather than focus on the players and their achievements.

NL Books on player achievements, statistics and personalities have already been done. My goal for this book was to report on how the League operated, the problems they faced, how they dealt with them, and what they meant as an institution in the black community.

JJM What role did baseball play in the black communities prior to its integration?

NL Boxing and baseball were the two most popular sports in the black communities during that era. Baseball was especially popular in the South, and when many African Americans moved north during the first half of the twentieth century, they brought their love of baseball with them. It was not only popular in the black communities at the professional level, but on the sandlot and semiprofessional level as well. Many black fans of the era also followed white major league baseball, probably more so than they do today.

JJM You quote Birmingham Black Baron player Piper Davis as saying, “In Negro baseball, the players advance purely on natural talent and not much more. Their basic shortcoming is that they do not learn the fundamentals of the game.” What was the caliber of play in the Negro Leagues?

NL The caliber of play was very high. I think what Davis meant by that comment is that they didn’t have the coaching and instruction they would get in the more formal environment of white minor or major league baseball. One of the biggest problems many Negro League officials and players would talk about was that young players didn’t get very much training. Players might be scouted and given one or two chances to show their abilities. If they didn’t do well they were pretty much discarded, because there weren’t minor leagues attached to the Negro Leagues — either you made it or you didn’t. There was very little instruction available to them, certainly nothing like what the minor leagues offered budding white talent.

While the caliber of play in the Negro Leagues was very high, the thing that probably made it less than that found in the major leagues was that they didn’t play as many games against top teams. They played one hundred sixty games or so a year, but the level of competition would differ very much from day to day. Many of the games would be against weaker white semiprofessional teams. This inconsistent level of competition hurt the overall caliber of play. Another factor to consider is that the roster size in the Negro Leagues was in the neighborhood of fifteen players per team, whereas in the majors, there were twenty-five.

JJM Josh Gibson said “Dozens of us would make the majors if given the opportunity to play under the same circumstances as the whites regular schedules, modernized traveling facilities, with none of these 500 – 800 mile overnight bus hops, and board and lodging at the better spots.” Did white players acknowledge the abilities of the Negro League players?

NL Certainly some of them did, particularly by the thirties and the forties when Negro League teams played more in the major league ballparks. The Negro League teams rented these parks, and their playing in them provided white players an opportunity to learn about the abilities of the players. Also, there was frequent barnstorming in the postseason, where major league players would often play against the best black players. So, they were constantly cognizant of them, and an open-minded major leaguer would be likely to appreciate the talents of a Josh Gibson or a Satchel Paige.

JJM A major theme of the book is how fragmented the team owners were. Their backgrounds were certainly less than sterling — many got ahead in life through illegal activities, although it is easy to understand why given the few opportunities available to minorities in that era. When referring to the animosity among the league owners, Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey said the Negro Leagues was an organization with “three pulling one way and four pulling opposite.” What were the deep divisions that existed between the team owners?

NL I like that quote because it certainly fits them to a tee. During the sixties, National Football League Commissioner Pete Rozelle said he wanted his owners to think “league” and not “team,” and I have been using that as an analogy for what the Negro League owners were going through. That is certainly a delicate balance to achieve in professional sports, because while team owners are competitors, they are also partners, and it is important to build what is best for the League as well as the team. Typically, the owners of Negro League teams were out for themselves. They wanted to do as well as they possibly could, and if the League suffered in the process, that was okay. What they needed was strong outside authority — such as a strong commissioner — who would push for the best interests of the league and get the owners to work toward the same goal. But they were most concerned with what was best for themselves and let League policies fall by the wayside.

As far as the backgrounds of the owners, as you mentioned, many of them had success in the underworld, particularly in the numbers lottery, which was very popular in urban areas around the country. People would place bets on a three digit number, which would then be selected in a theoretically impartial fashion. A few of the Negro League owners made a good deal of money on this in the thirties, and they invested some of their profits in legal businesses like baseball. Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee, for example, was an important force in revitalizing the Negro Leagues in the thirties, as well as Abe and Effa Manley of the Newark Eagles and a few others.

JJM Wasn’t Greenlee pretty instrumental in pushing — albeit indirectly — Branch Rickey toward signing black players through his creation of the United States Baseball League?

NL Possibly. Greenlee had been out of baseball, and in the mid-forties was trying to get back into the Negro National League, but they wouldn’t let him in. As a result he started the United States Baseball League (USL), and one of the things he did do was get Rickey involved, although by that time I think Rickey already had ideas of integration. One of the things that Rickey was hoping to achieve through his involvement with the USL — he put a USL team in Brooklyn — was having a league in which he could develop black talent to call on once integration of major league baseball was up and running. He also hoped that by having a black team play in Brooklyn, he could get the fans used to the idea of seeing black players on an every day basis.

One thing about Greenlee is that he was always thinking “outside the box,” and in a much more progressive manner than the other owners. The idea that he actually affiliated with Rickey in the mid-forties and was thinking ahead toward integration was something that most of the other Negro League officials were not doing.

JJM Regarding the integration of major league baseball, White Sox president J. Louis Comiskey said in 1933, “The question [of integration] has never crossed my mind. Had some good player come along and my manager refused to sign him because he was a Negro I am sure I would have taken action or attempted to do so, although it is not up to me to change what might be the rule. I cannot say that I would have insisted on hiring the player over the protest of my manager, but at least I would have taken some steps — just what steps I cannot say for the simple reason the question has never confronted me.” When was integration of baseball first discussed by major league baseball?

NL While the idea of integration had been out there, it began to be seriously discussed in 1933, which is actually the year my book begins. A campaign to integrate baseball during the Depression was begun by a New York newspaper as an idea to help sagging attendance in both the major and minor leagues. The black press actually kind of ran with that, and in 1933 attempted to solicit the opinions of major league officials on the subject. They weren’t too aggressive — which was understandable considering the time period — they just wanted to take a more investigational approach and attempted to report on major league baseball’s attitude toward the subject.

The Comiskey quote you read was pretty indicative of how many of the owners responded, in a kind of double-speak. They didn’t want to admit that a color line existed, and would not answer how they would deal with integration because, in their view, the subject had never come up. Therefore, everyone danced around the issue. Major league baseball officials were never stupid enough to admit to excluding blacks, but they would suggest that the players were not good enough, that the idea had never been suggested, and things like that. The pressure on major league baseball intensified throughout the thirties and reached its peak during World War II, when American society itself was changing so dramatically, and when the issue of race was being examined in a substantially different way.

JJM In 1937, Brooklyn Dodger official Steven McKeever made a statement that he would sign Satchel Paige pending his manager Burleigh Grimes’s approval. In 1939, Pittsburgh Pirates president William Benswanger casually offered to purchase Josh Gibson. So, it doesn’t sound as if either of those situations were close to happening.

NL No, I don’t think so. Benswanger was probably the most interested in doing it. Benswanger actually could have been the Branch Rickey of the whole story. As the owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, he knew of Negro League Baseball because the Homestead Grays would also play their games in Forbes Field. He knew of Josh Gibson and in 1939 asked Grays owner Cum Posey if he would sell Gibson. Three years later, in 1942, he announced that he would hold a tryout for various players, but he wilted under the pressure, and the tryout was never held. I think his heart was in the right place but he just didn’t have the strength to be the first to sign a black player. That is what differentiated him from someone like Branch Rickey.

JJM You wrote, “On February 16, 1948, Branch Rickey addressed a gathering at the annual football banquet at Wilberforce University and disclosed that after the signing of Jackie Robinson, his fellow owners had unanimously adopted a report suggesting that black players would jeopardize the profitability of major league baseball.” Is there evidence suggesting that major league owners conspired to block integration of baseball?

NL That is actually a very interesting story, and it is sort of a myth that has been perpetuated for fifty years now. This was part of a larger report. During 1946, the major leagues were wrestling with a lot of potential problems. There was talk of a players union, defections to Mexico, and the issue of integration was hot on the radar screen. Major league baseball officials created a committee to discuss these issues and publish a report. Part of the report was a three page section on the issue of race and what had happened since Jackie Robinson signed in 1945. The report did not show a particularly positive reaction towards the integration of baseball, and it speculated that investments may be at risk since integration could potentially alienate fans. This report — of which integration was one of the issues — went before all of the major league owners, who voted to approve the findings of the report. The part of the report that speculated on the affects of integration was actually removed before it was sanctioned by the league. So, it is possible that Branch Rickey was distorting this report when he made this speech in 1948. While it is possible the owners did conspire against integration — and we can’t possibly know whether they did or not — this notion that major league baseball owners voted fifteen to one to prevent Robinson from joining the Dodgers comes up a lot, but it is not true.

JJM The black owners had a tough situation, because on the one hand they were business people depending on an enterprise that was beholden to the institution of segregation, yet on the other hand, they wanted to break down the social barriers for blacks as well. In 1949, Robert Kinser and Edward Sagarin described this as the “antagonism between the appeal for solidarity and the aspirations of the people.” How did the black owners deal with this?

NL It was probably very difficult for them. These were business people who really had to struggle to make this enterprise financially solvent. During the forty year history of the Negro Leagues — between the early twenties and the early sixties — only five or six years were profitable for the majority of teams. Most of the time they didn’t make money, but here they were in the forties finally making money while at the same time there is a tremendous push for integration. Consequently, it was very hard for them to support integration because they knew it would hurt their business a lot. It isn’t as if they were opposed to integration — as this was clearly what African Americans wanted — but it would harm their chances to survive. As a result they pussyfooted around this issue and didn’t have much to say about it, and they took quite a bit of criticism for their stance. One of the owners, J.B. Martin of the Chicago American Giants, basically said that integration is something they can’t take responsibility for and that it wasn’t really their business, which wasn’t the stance to take from a public relations standpoint. They certainly could have handled the issue better, but since they were so wrapped up with the major league teams at the time — particularly because they rented the ball parks — they didn’t want to rock the boat by saying anything about integration.

JJM Well sure, having access to major league parks was crucial since paid attendance was their only revenue stream, and their best chance to draw large crowds was in these stadiums.

NL Yes, they made all of their money on attendance, and since in most cases they were renting parks from major league owners, a piece of their income would go right back to them. Negro League owners had to put bodies in the stands, and if they didn’t, they weren’t going to make any money, so they were so very dependent on that. Another problem they faced was that rents in parks like Comiskey in Chicago and Yankee Stadium in New York were so high that unless ten thousand fans attended a game, not that much money was being made. This is one of the issues Negro League owners had to face during the integration of major league baseball; as attendance dropped, it was no longer cost effective to play in major league parks.

JJM It was all part of the price Negro League owners paid for not building a coherent policy concerning how to deal with integrated baseball.

NL Yes, that is something I focus on in the book. There did seem to be a considerable amount of short sightedness among the League owners, and they were quite naïve in their dealings with the major leagues. In 1945, one of the League officials said they met with a major league official concerning integration and were promised that if anything were to happen regarding integration, the Negro League teams would be properly consulted and compensated. This of course did not happen at all, because when Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson, the Kansas City Monarchs were not compensated. Clearly they should have prepared more for integration because it was so evident that it was coming in the mid to late forties. If they had strengthened their player contracts or if they tried to work out some tentative agreement with major league baseball, they would have been in a better position once integration occurred in 1945.

JJM We interviewed Negro League player Buck O’Neil a year or so ago, and he felt that baseball would be integrated by putting a Negro National League team in the National League and a Negro American League team in the American League so there would be two entirely black teams in major league baseball.

NL I don’t think that would have happened in the forties, although that was definitely a thought during the twenties. When you look at the perspective of the World War II era, O’Neil’s suggestion would no longer be acceptable because it wouldn’t really result in integration, it is simply segregating within an institution. I am not sure if the liberal segments of the American public and blacks themselves would have accepted an all black team.

It is interesting to remember that Satchel Paige — who was often the one everyone thought was being discriminated against — felt uneasy about going into the major leagues because he was making a good amount of money in the Negro Leagues. He did, however, often suggest what O’Neil did: put a team in the American League from the Negro Leagues and field an all black team. Perhaps that would have made sense from Paige’s perspective, as he probably would have been better protected in that kind of environment. A player going into the majors alone, as Jackie Robinson did, likely would take a lot more abuse, and that is what Paige was probably thinking.

JJM Paige actually spoke about this, at one time saying, “You writer fellows stink. You keep on blowing off about getting us players in the league without thinking about our end of it, without thinking how tough it’s gonna be for a colored ball player to come out of the club house and have all the white guys calling him ‘n—-‘ and ‘b—-k” so-and-so.’ What I want to know is what the hell’s gonna happen to good will when one of those colored players, goaded out of his senses by repeated insults, takes a bat and busts fellowship in his damned head?” Was this statement one of the reasons Paige was not major league baseball’s first black player?

NL It is likely that Paige was reluctant because of the abuse he was going to take in the major leagues. Beyond that, Paige wasn’t taken for a couple of other reasons, a notable one being that he had a track record of being pretty unreliable. He didn’t show up to play on occasion, for example, and often wasn’t cooperative with authority figures. By the forties, the Kansas City Monarchs had to clamp down on him. So, his reputation was such that it may have prevented serious interest among major league teams for his services. Also, at the time of Jackie Robinson’s signing, Paige was thirty-nine years old, so his age may have prevented him from being an attractive candidate for Branch Rickey. When Paige was eventually signed in 1948, there was considerable controversy from the forces of the major league establishment — many considered it a joke because he was forty-two years old and were saying he couldn’t pitch anymore. He actually acquitted himself quite well by having a very good year in 1948.

JJM A couple of other issues may have contributed to Paige not being first as well. If Paige had been the first and at age thirty-nine — an age when an off season is likely — it would have been easy to say integration was a failed experiment, which was something Rickey wanted no part of. Also, the journalist Scott Simon, who wrote a wonderful biography of Jackie Robinson, said that Rickey and the major leagues didn’t want a pitcher to be the first black player — particularly someone with a personality like Paige’s — because they were afraid that a bean ball would create serious problems.

NL I don’t know if I agree with that. One thing people often forget is that Branch Rickey signed a bunch of other black players within six months of signing Robinson who might have beaten Robinson to the majors. For example, the second player he signed was John Wright, who was a good pitcher with the Homestead Grays. Because Wright had a successful career in the Negro Leagues, many people thought in late 1945 and early 1946 he could be the first black player in the majors. Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley actually stated in early 1946 that Wright might have a better chance at making the majors than Robinson. In some ways it may have been easier for a pitcher to succeed because he wouldn’t have to play every single day and therefore wouldn’t be subjected to as much abuse. As it turned out, John Wright played in the minor leagues in 1946 but was never able to make it to the majors. Yet had Wright succeeded in 1946 and Robinson failed, it could very well have been Wright who went to Brooklyn in 1947 and not Robinson. These are just alternate possibilities that might have occurred.

JJM How did the advance of technology of the era — specifically radio — impact Negro League baseball?

NL There are many intersecting forces in the late forties that were changing the face of American leisure and American sports — integration being one of them. Also, with the advance of the mass media during the late forties and early fifties, radio broadcasts of major league baseball were readily accessible. Not only did it make it easier for black fans to follow some of the integrated major league teams, but it also impacted the popularity of the minor leagues, because once major league baseball became available on the radio, it diminished the appeal of the minors. And as television broadcasts of major league games increased, it had an even more damaging impact on the minor leagues.

We don’t know specifically how the media coverage of major league baseball affected the Negro Leagues, although we can certainly speculate that in cities like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, where major league broadcasts featuring integrated teams were available, it diminished the appeal of their games. It is safe to say that virtually every non-major league baseball organization was hurt during this era, because once fans were exposed to the best on television, everything else became less appealing, and it made the Negro Leagues even more fragile.

JJM Some of the Negro League player statistics are pretty amazing. For example, Josh Gibson is reputed to have hit .542 one season. How reliable are the Negro League statistics?

NL Unfortunately, the statistics are not reliable. After the games, League statisticians were dependent on the owners or managers to submit their box scores to a central office, where the numbers would be compiled. Often, the statistics were not even submitted, which would skew the results. There are currently ongoing attempts to compile the statistics in a more systematic fashion in hopes of coming up with something more accurate. The difficulty with this, of course, is that we don’t have a box score for every game played, and the box scores we do have may not have all necessary information. As a consequence, I don’t believe we will ever have one hundred percent accurate Negro League statistics, but we do have a better sense of them today than we did in the past.

The inaccuracy of the statistics is extremely frustrating. While I was doing the research for the book, I would often wonder how in the world they could mess up something as essential as statistics? It is such a basic thing in baseball. A major appeal of baseball is statistical comparisons, but because the administration of the Negro Leagues was so weak they never could quite get their act together around this issue. They could never get all League owners on the same page regarding it. By the late forties they were getting a little better, and they made some administrative changes after integration that they should have made much earlier, but the statistics were never really an asset to the League.

In general, the League publicity was never very good. They depended on the black newspapers for publicity but they were often not cooperative with them as far as getting information out to the fans. Many of the black newspapers were frustrated with the Negro Leagues, complaining that they couldn’t get the information they needed. The black sports writer Sam Lacy said at one point that his newspaper offered to pay for the results of the game, and even then they didn’t receive cooperation.

JJM Regarding the issue of publicity, Gus Greenlee’s publicity agent John Clark said, “The majority (of owners) will not pay 60 cents or one dollar for a scorebook. Nor will they pay to have records kept and transmitted of the game played. Their general conduct is more like first-year sandlot promoters than big league owners.”

NL Yes, and I think that demonstrates how Negro League baseball was in this “in between stage.” The caliber of play was major league, but the administration of the League was almost semiprofessional. Everything was very casual — the scheduling, the compilation of statistics — and very unstructured. Granted, sometimes they were in the semiprofessional baseball world because they would play white semipro teams, but they were a professional league that straddled these two worlds.

JJM This lack of structure really contributed to the demise of the League. The social changes taking place likely would have eliminated the League anyway, but what kept money out of the owners’ pockets and seemed to expedite their demise was that they rarely signed players to contracts. This left them vulnerable to major league teams who could sign players without the need of paying out compensation.

NL Yes, not signing players was a big mistake. The issue of contracts had been around in the thirties and forties, particularly when some of the foreign teams from the Dominican Republic and Mexico were taking players. While some teams did have contracts, they weren’t even notarized, which meant they didn’t have much legal force. Other teams didn’t use contracts at all, including the Kansas City Monarchs, for whom Jackie Robinson played before Branch Rickey signed him.

I think the reason behind not using contracts was that they felt if they had contracts, other players would find out their value and would likely ask for more money. Also, it was easier to release an unsigned player because they had no legal obligation to him.

JJM Or if they got hurt…

NL That’s right, and I think they preferred that kind of non-existent obligation. Of course, as you mentioned, the consequence of this is that when major league teams came calling, Negro League teams took quite a hit. The Monarchs didn’t get a penny for Robinson, nor did the Newark Eagles for Don Newcombe or the Baltimore Elite Giants for Roy Campanella. So, while these players became a cornerstone in the success of the Brooklyn Dodgers during the late forties and fifties, Negro League teams didn’t get a penny for them.

On the other hand, major league baseball did recognize contracts that were in force, although they didn’t pay very much for players under contract. The largest sum paid out for a Negro League player may have been fifteen or twenty thousand dollars — the Newark Eagles got approximately fifteen thousand for Larry Doby, which is about the same the Birmingham Black Barons got for Willie Mays and the Indianapolis Clowns got for Hank Aaron. But that was about what these teams were going to get in that period, and most player sales were considerably less. The Negro Leagues tried to survive on player sales in the late forties and early fifties, and the Kansas City Monarchs were most successful at that. They sold a number of players and were able to keep afloat by developing players for the majors, but it was a difficult battle.

JJM And any hope the Negro Leagues could have become part of the minor leagues seemed to dwindle with the developing media and how it diminished financial opportunity at that level. There was very little money in it for the owners to pursue the idea of becoming minor league franchises.

NL Yes, their inclusion in the minor leagues had been the hope at one point during the thirties. In 1937, Negro League Commissioner Ferdinand Morton had actually been in contact with major league baseball about the Negro League being assimilated into the minors as a sort of pathway to integration, but nothing came of it. After integration had occurred, there was a more formal attempt by the Negro Leagues to affiliate with Organized Baseball as a minor league, but they were rejected. If they had been accepted, I doubt that it would have spared them from the problems the white minors were currently facing, but it would probably have put the Negro League in a better position. Being a part of Organized Baseball would have provided them with a little better opportunity for success.

JJM When was the last Negro League baseball game?

NL I don’t know that for sure. The last mention of the League that I was able to find during my research was in Jet magazine during the fall of 1963. The Indianapolis Clowns, an all black team that eventually became like the Harlem Globetrotters of baseball, actually continued to tour the country as late as 1984.

JJM I was pretty astounded by that. After all, the Clowns were known for painting their faces and wearing grass skirts. It is hard to believe this would be accepted as recently as 1984.

NL I was shocked by that also. In fact, my editor thought it was a typographical error and actually crossed it out. While I guess you could compare the Clowns to the Globetrotters in some ways, they were actually more outlandish. As you say, many of the players were painting their faces and didn’t project themselves in a positive fashion the way the Globetrotters seem to.

JJM As you mentioned earlier, Hank Aaron played with the Clowns…

NL Yes, that is right. When the Clowns were in the League, some of their players would do comedy routines for the fans before the game or in between innings, but Aaron was not a part of that. He only played with them for a few months but he was tearing the League apart, and the Boston Braves eventually signed him.

JJM Sportswriter Dan Burley wrote, “Negro baseball was so poorly organized and managed that it was an open target for any situation that might produce a threat.” Realistically, given the momentum for integration, would anything have saved Negro League Baseball?

NL It is possible that they would have been a little stronger had they been better organized, but even a strong, well organized league would have been butting up against all the forces within American society, and it is hard to imagine a segregated league succeeding. Beyond that, they would have fallen victim to the advancing technology, which really made it difficult to compete with major league baseball.

With the advent of integration, many black institutions failed as they outlived their purpose. The black institutions that survived and flourished after World War II were those that had some larger purpose, that were not just standing as a segregated version of a white institution. Black newspapers, for example, did very well in the post-war era because they still had a viewpoint to express. I don’t sense that black fans felt connected to the Negro Leagues once integration of major league baseball occurred. They had served their purpose and society had grown beyond what they could offer.

JJM Sportswriter Randy Dixon wrote, “I see no reason why anyone should patronize anything just because it is a Negro proposition unless the proposition has enough merit to stand on its own feet.”

NL Yes, and I think what Dixon was referring to in particular was this notion that blacks should support their own enterprises. At one time that was a very powerful ideal — that blacks should support their own businesses even if they have flaws — and the flaws should be ignored. In his statement, Dixon was communicating the viewpoint that blacks shouldn’t support black enterprise forever unless they are valuable to the community. By the late forties, the Negro Leagues had done what they set out to do. Somewhere in the book I quote another sportswriter who comments about how nobody has really looked at the Negro Leagues as anything other than being a vehicle to integration, and we should not hold up progress because this vehicle may be faltering and having problems now.

JJM Yes, in a pretty harsh account, the Pittsburgh Courier reporter Wendell Smith wrote, “Few, if any, of the owners are sincerely interested in the advancement of the Negro player, or what it means with respect to the Negro race as a whole. They are only concerned with the preservation of their shaky, littered, infested segregated baseball domicile.”

NL Very harsh, yes. Wendell Smith was very tough on the Leagues, and at the same time he was a powerful advocate for major league integration. He was often right on target, but that quote indeed was a bit harsh. I think some of the owners were quite sincere and did want to benefit black players. And it is important to mention that some of these owners were white, which made it quite difficult for them, particularly when issues of integration were being raised. The Kansas City Monarchs owners were white, and they were sort of put behind the eight ball when it came to integration with Jackie Robinson.

But I do think some of the owners were sincere, and they had to balance that with their need to make money. I don’t think I would paint them in such a sinister way as Smith did, but his attitude reflects how attitudes were changing as integration was on the horizon. While integration was still largely token in American society at the time, it was on the national radar screen and people were no longer going to accept segregated facilities and segregated institutions as they had in the past.

JJM One final Wendell Smith comment may capsulize this. He said of Newark Eagles co-owner Effa Manley, “She blamed every one for the demise of her dream world and refused to recognize that nothing was killing Negro baseball but Democracy.”

NL Yes, Smith said it perfectly. Because America was finally living up to its ideal of democracy, it would result in sacrifices for some people, but in the long run, the integration of baseball would benefit the greater number of people and recast our entire society.

.

.

“…the remarkable survival of professional black baseball provided an institutional basis for fostering the skills of black athletes and to a lesser extent, black entrepreneurs. Because of this institution-building in the black community, a pool of talented African American athletes developed who were able to take full advantage of the greater opportunities that became available with desegregation. As (Philadelphia Stars pitcher) Tom Johnson later observed, ‘in the absence of the opportunity, the blacks created that opportunity, created…a baseball world for themselves, so they could demonstrate their abilities. And so many of them were ready when the doors were opened, so from that vantage point I felt that we were winners.'”

– Neil Lanctot

.

.

__

.

.

About Neil Lanctot

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

NL I grew up in New England so I followed the Red Sox and admired whoever their star player was at the time, although in retrospect it seems as if they were always failing. I can’t say I followed one particular player, and none could be considered my childhood hero.

.

___

.

Neil Lanctot teaches history at the University of Delaware. He is the author of Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and The Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932.

.

.

This interview took place on June 7, 2004, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interviews with Negro League baseball player Buck O’Neil and Jackie Robinson biographer Scott Simon.

.

.

*

# Text from publisher.

.

.

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

Fabulous!! The truth the whole truth, nothing but the truth…

Fabulous!! The truth the whole truth, nothing but the truth…

I enjoy anything about the Negro Leagues because little nuggets of knowledge make me want more.