.

.

“Music Depreciation” was a finalist in our recently concluded 65th Short Fiction Contest, and is published with the consent of the author.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Music Depreciation

by Dr. Martin Blinder

.

…..Mr. Roberts was my one and only piano teacher. Instruction began when I was age 7 and continued weekly until I went off to college.

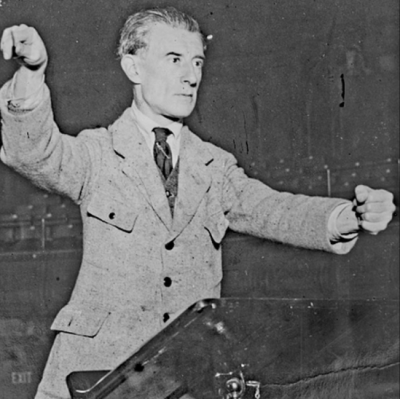

…..I’ve since come to understand why he had a waiting list and why so many considered him the architect of their pianistic careers. Belatedly I can appreciate how his passion for the classics inspired his students to bring a luminosity and sentience in performances already flawless technically.

…..But Mr. Roberts never grasped the ways my musical ability, such as it then was, differed and did so sharply from his and from that of his many conventionally-gifted students. Though only a several decade difference in our biological age, musically he and I were centuries apart. As a consequence, ten years ostensibly devoted to my development as a musician, if not entirely squandered, were largely misdirected.

…..Mr. Roberts’ fee was perhaps twice that of any neighborhood piano teacher, of whom back then there was an abundance, all eager to provide instruction to anyone content to, say, bang out “Heart and Soul” or “Happy Birthday.” Mr. Roberts would only take on those he thought showed real talent.

…..Presumably he sensed something of the sort when he agreed to add me to his roster. Likely he knew of my illustrious cousins, Naoum and Boris Blinder, then concertmaster and first cello respectively of San Francisco’s Symphony Orchestra, and perhaps hoped I might share in their genetic endowment.

…..I had never thought of myself as in any way “gifted.” Adults think in such terms, children rarely. I was simply a restless kid who had no idea what it meant to “sit still for a minute, will you,” who loved dogs and climbing trees and seeing how high I could pump the playground swing. Stuff like that.

…..As regards music, four prognostically ominous revelations emerged my very first week of Mr. Roberts’ instruction:

…..I didn’t much like piano lessons.

…..I didn’t much like practicing the piano.

…..I didn’t much like the music Mr. Roberts had me learn.

…..I didn’t much like Mr. Roberts.

…..He was a man who saw the classical composers touched by the gods if not themselves divine, their compositions immutable sacred texts. All tampering verboten!.

…..To my ear, however, traditional classical music was predictable, repetitious, and well, something of a bore. [My apologies, devotees of Mozart, et al. Understand I do not claim consecrated validity for my perceptions nor do I in any way intend the slightest denigration of the Great Composers’ individual or collective genius. I’m just being straight about one of my limitations.] The sad fact is that few classical compositions “speak to me” in the way they do for others, neither capturing my ear, touching my heart, engaging my brain, lifting my spirits, transporting me to a higher consciousness, nor compelling me to sing or dance or tap my foot. Of particular relevance was the failure of these iconic composers to inspire me to sit at the piano for hours on end and learn to play what they had written decades ago so that – in Mr. Roberts’ resonant words – “Beethoven might live again.”

…..Left to my tender mercies Beethoven and his compatriots would remain six feet under. Okay, admittedly scattered here and there was the odd classical piece I did enjoy – a Mendelssohn Scherzo, Tchaikovsky’s lyrical melodies, the harmonic adventures of Scriabin. See – I’m not a complete Philistine. And – did you know – once in a great while Chopin would slip in an honest-to-God authentic impressionist chord – say a major Ninth – for a brief moment several decades ahead of its time. But not until I was introduced to the 20th-century composers like Debussy and Ravel – most decidedly not to Mr. Roberts’ taste – that classical music became interesting. And only when in my late teens I stumbled onto jazz and jazz improvisation did music actually become compelling – and ultimately a career consideration.

…..But what may have most distinguished me from Mr. Roberts and his other students – and which somehow escaped his notice until it was too late – is that as far back as I can remember music was always bouncing around in my head, though far beyond anything I could express on a piano keyboard with my stubby little fingers. But thanks to Mr. Roberts and his then unwelcome ministrations, my digits gradually caught up with my ear. As a consequence, I can in my mind craft a piece of music and simultaneously my fingers provide “instant playback” on the piano. In much the same way I can replicate the compositions of others, usually after just a single hearing. Once a piece of music, however obscure, makes it into my head (either by way of my ears or because I composed something of my own), I can then lay it or a reasonable facsimile on the keys in real time.

…..For example, I might return home after seeing a film that had a distinctive soundtrack, say, The Magnificent Seven (dah – – te dah-dah duh – – duh – – duh) and immediately sit down and reproduce on the piano what I just heard in the theater – not necessarily note for note but a credible copy. Or let me have your phone number (no zeros please) and after matching the numbers with the appropriate piano key (1 = A, 2 = B, and so on), I’ll present you with a mini-symphony based on a melodic theme initially laid out by your very own AT&T. But though my brain can readily deconstruct or “reverse engineer” almost any piece of music and reassemble it as I see fit, it must in the first place be fairly inventive if it is to hold a place in my short attention span.

…..I should note here that this capability would later prove profitable as it was instrumental in enabling me to play jazz at a professional level. But that was years in the future. For now let’s return to the bête noir of my otherwise idyllic childhood [right!] and how it enabled me to both deceive my parents and navigate (a cynic might say “circumvent”) Mr. Roberts’ well-intended but hugely uncongenial mentoring for ten musically dispiriting years.

…..It worked like this:

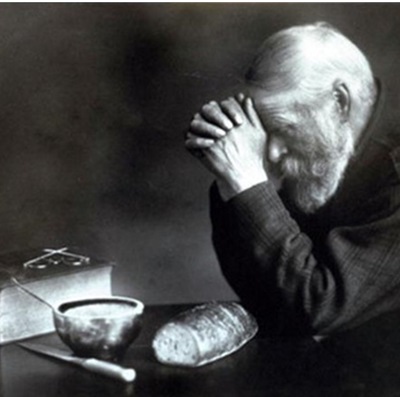

…..At the end of each weekly lesson Mr. Roberts would assign me half a dozen or so pieces I was to practice daily – perhaps a Bach fugue or a Haydn sonata. I was obliged by my parents to practice at least one hour every day, seven days a week if possible, Sundays and holidays included. And having been raised always to honor my father and my mother, for an entire decade this is what I did.

…..My mother, who in my memory seemed to be confined in perpetuity to the kitchen, was the acting capo. Mom didn’t have much of an ear. Absent some lyric, telling one piece from another was a challenge. But she could readily deduce from a protracted silence that I was no longer practicing my lessons. Having somehow accessed one of those Star-Trek transporters, in a flash she’d suddenly materialize behind me leaving no time to hide the comic book I’d just opened, now subject to confiscation.

…..In short, there being absolutely no alternative, I learned to play the piano. By the time my decade-long ordeal had come to an end there was probably no classical composer of note I hadn’t played – even if just a single composition. As things turned out, one was all I needed.

…..It was less than a year after Mr. Roberts first arrived that I found a way to maintain the flow of music for the full requisite practice hour virtually without interruption, pacify Mom – and most important, please myself. What neither my mother nor Mr. Roberts knew was that mastering the first page or two of my several assignments, be they pieces by Schumann or Schubert or Strauss, allowed me to identify and then recreate that composer’s distinctive chord progressions, his characteristic melodic figures, harmonic voicings, and most particularly his signature musical clichés (and all composers have them). I would then improvise for the next several minutes in the precise style that informed those first pages.

…..In other words, once I had absorbed a page or two of any composer’s musical mannerisms they were imprinted in that portion of my brain wherein the generation of music resides, enabling me to simulate the “sound” of that composer at will, much as certain Las Vegas comics can impersonate with startling verisimilitude the voices and gestures of almost any celebrity, living or dead. The infamous club of notorious forgers and counterfeiters now had a new member. Past members could deliver a “genuine” Rembrandt or crank out sheets of convincing $100 bills. I could channel Rachmaninoff.

…..I might begin my practice hour playing an assigned lullaby recognizable as authentic Brahms. But slowly Brahms would morph into a hybrid Brahms / Blinder lullaby and finally “pure authentic Blinder” pretending to be Brahms. I was to get away with this deception for years because first, my ersatz Brahms was musically “plausible,” constructed as it was from “specs” graciously provided by the composer; and second, my mother would be hard pressed to tell Chopin from “Chopsticks,” let alone faux Brahms from genuine Blinder.

…..In short I could take, say, ”Jingle Bells” or “Blue Moon” or the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” or for that matter any of my own tunes, and play them so that they sounded as if they had been written by any composer you care to name – provided I was familiar with at least one of his compositions. What I was putting out would never rank as great music but, at least on my good days, was a convincing, perhaps even an inspired simulation – but still just a plausible approximation of the real thing. Or arguably the piece was composed when the great man himself was not at his best, possibly under the weather with a case of the flu or acute constipation.

…..So it is that today that I am able to confound – albeit briefly – classically-trained musicians who, having prided themselves on mastering a particular composer’s complete repertoire, listen to one of my pianistic sleights of hand and wonder how after all these years it was possible that they knew nothing of this particular composition? One of those “long lost” masterpieces, perhaps . . .?

…..Which brings us back to our young sociopath’s formative years and his perplexed and hugely vexed piano teacher. Mr. Roberts had a rather loud voice. Several times I had overheard him in our kitchen telling Mother of his bafflement by my quite impressive mastery of the first page or so of my several assignments, only to stumble through the pages that remained.

…..Mother assured him that I had practiced diligently and without respite for the entire hour, of course not knowing that most of what I was practicing was my counterfeit Haydn or my ersatz Soleri’s ersatz Mozart. Thus, under my mother’s inadvertent protection, my facility for shameless improvisation grew. In the end it got so good I could sit at the piano and read that comic book while my fingers automatically did the playing. It seemed there was now no impediment to my downhill slide into an irredeemable antisocial personality disorder.

…..Until late one afternoon on piano lesson day. A scheduling mix-up (precipitated as I recall by a switch out of daylight savings time) brought Mr. Roberts to our home one inadvertent hour early – and as it so happened, at the start of my practice period that day.

…..So unbeknownst to me, in the parlor happily absorbed in my pianistic fraud, Mr. Roberts was in our kitchen chatting with Mother. I’m sure it wasn’t long before their conversation petered out as Mr. Roberts at last heard why for almost ten years his promising pupil’s many hours of allegedly diligent practice lost their efficacy once past the first several dozen or so measures.

…..THE JIG WAS UP!

…..But that wasn’t quite the end. Years later, my mother (aka inadvertent de facto co-conspirator) in a reminiscent mood shared with me what she recalled of what happened next: Mr. Roberts not only resigned but offered to refund all the fees my parents had paid him over the past decade. Of course my parents would have none of that.

…..My father had arrived moments after my exposure. He and Mother assured Mr. Roberts that my misspent decade was no reflection on him but another example of their ongoing problem with me. Though a somewhat superior student overall, to their distress I had developed a pattern in which I’d come upon something “new and exciting,” throw myself into it, giving it more and more of the time and energy once devoted with no less passion to its predecessor. For awhile I’d be able to manage both. Until a third thing would come along . . .

…..“What most worries me,” my father explained, “is that Martin leaves in his wake a host of impressive but unfinished, incomplete projects. Just on the verge of success he’ll get caught up in something else. It’s hardly your fault that his entire musical repertoire is a hodgepodge collection of initial fragments. I’m afraid he has a life ahead him of – of – ”

…..“Near misses”, my mother suggested.

…..“Yes,” my father agreed, “near misses.”

…..A problem I have yet to outgrow.

.

.

___

.

.

Dr. Martin Blinder is a jazz pianist who practices psychiatry in his spare time.

.

___

.

.

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

Click here to read “Ballad,” Lúcia Leão’s winning story in the 65th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to read more short fiction published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here for details about the upcoming 67th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

.

.

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.