.

.

.

.

Tad Richards, author of Jazz With a Beat: Small Group Swing, 1940 – 1960 [SUNY Press]

.

.

___

.

.

…..Just when you think you’ve read it all regarding jazz history, along comes Tad Richards’ Jazz with a Beat, Small Group Swing, 1940 – 1960, a compelling, intelligent, and fresh look at those who performed “small group swing jazz” – a term Richards coined to describe a genre of the music that was commercially viable to the era’s Black audience, but not accepted as “real jazz” by the critical establishment.

…..Small group swing was an adaptation of the big band Black swing of the 1930s (think Erskine Hawkins, Jimmie Lunceford and Chick Webb) to small combos, whose vigorous rhythms were beloved by Black audiences of the 1940s – and influenced the rock and roll of the 1950s and soul jazz of the 1960s.

…..While small group swing was shunned by the jazz critical establishment for being too flamboyant and too close a cousin to the emerging (and despised) rock and roll, Richards makes the case that small group swing players like Illinois Jacquet, Louis Jordan, Big Jay McNeely, Joe Liggins, Red Prysock, T-Bone Walker and Ray Charles played a legitimate jazz and a more pleasing listening experience to the Black community than the bebop of Parker, Dizzy, Bud Powell and Monk.

…..Richards writes that “the progressives, who ruled the critical day, stressed innovation and complexity, sometimes at the cost of drive and immediacy. The small-group swing combos, the rhythm and blues players, the purveyors of jazz with a beat, stressed that drive and immediacy, and they captured the hearts and the hips and the dancing feet of the day.”

…..The modernists of the era Richards focuses on saw themselves “in the vanguard of a new art form, a music that was to be taken seriously as Art with a capital A, not one that pandered to the masses.” Their music was considered “real jazz” with “artistically pure roots,” in comparison to those who performed “jazz with a beat” – a group of artists shunned by many of their fellow musicians and panned by the critics as being created for its commercial opportunities and who were not presenting jazz as a “high art.” The legendary jazz critic Leonard Feather even left most of the key players of small group swing out of his 1955 Encyclopedia of Jazz, a book seen by critics, musicians and record collectors at the time as a major contribution to the literature of jazz.

…..Richards tells this absorbing story from its 1942 beginnings (initiated with Illinois Jacquet’s lively solo on Lionel Hampton’s “Flying Home”) to 1960, when artists like Jimmy Smith, Cannonball Adderley and Ray Charles “broke the mold” because their recordings began receiving critical reviews in established jazz publications like Downbeat. It is a fascinating era, filled with major figures and events, and centered on a rigorous debate that continues to this day – is small group swing “real jazz?”

…..I spoke with Richards about it during our February 19, 2024 conversation.

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

“Illinois Jacquet played his first solo [on “Flying Home”] in a Lester Young style, then decided that for his second solo, he wanted to do something really different. Improvising on the fly, he started with a strongly emphasized note, then played the same note again, then again. How long could he keep it up? Nine more times, the same note, then a little coda, then back to it again, again the same note repeated twelve times, before picking up the melody again. The effect on listeners in 1942 was electrifying, but more immediately, Jacquet had electrified his bandmates. There’s a heightened excitement when the ensemble swings back into action, and the recording climaxes with Hampton and trumpeter Ernie Royal trading single notes to keep that excitement going.”

-Tad Richards

.

Listen to the 1942 recording of Illinois Jacquet (in Lionel Hampton’s orchestra) playing Hampton’s and Benny Goodman’s composition “Flying Home”

.

___

.

“Also in 1942, a group called Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five had their first hit records on Billboard’s Harlem Hit Parade chart. “I’m Gonna Leave You on the Outskirts of Town” went to number three, and it was followed with his first number one, “What’s the Use of Getting Sober “When You’re Gonna Get Drunk Again).” Jordan, an alto sax player and vocalist, had been with the Chick Webb Orchestra; when he started his own group (although he called them the Tympany Five, there were rarely exactly five members), he hoped to recreate the sound and the feeling of Chick Webb’s ensemble with a small group. Jordan would go on to have one of the most popular Black groups of the 1940s”

-Tad Richards

.

Watch a 1946 performance of Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five play his composition “Caldonia”

.

.

JJM Thanks for joining me to talk about your book, Tad. I found it fascinating and learned a ton about musicians who have not received the attention they deserve, primarily because of the musical path they chose. What is your background?

TR I am a music lover, and I am a writer. Oddly enough, in 1992 I wrote my first music book, The New Country Music Encyclopedia, so I’ve always loved all kinds of music. I have written three dozen books, both fiction and non-fiction, so writing is what I do.

JJM Why did you choose to write about this particular history?

TR I’ve always loved that music – it has long been a passion of mine. When I first got in touch with my publisher, SUNY, I had been blogging about Prestige Records, and I offered them my five-volume listener’s guide to every record ever made for Prestige, but it was more than they were able to handle at the time. I knew they had started a series called “Jazz Styles,” and I told them that I had an idea about a jazz style that no one else would be writing about because it’s not generally recognized as a legitimate jazz style, but it is, and here is my chance to put it on the map. Richard Carlin, the editor of the series, was very receptive to the idea, although he said we really can’t call it “rhythm and blues,” and I realized he was right, because that is such a big label that covers so many different kinds of Black music. So, we had to come up with a term for it, and “Jazz With a Beat” was the title of an early Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis album, so that worked, and I invented “small group swing” out of thin air, and now I’m hearing other people using it, so I guess it was a phrase that needed to be coined.

JJM You begin the book in 1942, when Illinois Jacquet played his famous solo on “Flying Home” while he was in Lionel Hampton’s orchestra…

TR His solo on that song was so fundamental to small group swing. Nobody else had done anything quite like that before. Big Jay McNeely said that Jacquet’s solo on “Flying Home” led to everything he would ever do. At around the same time, Charlie Parker recorded his famous solo on “Sepian Bounce” while playing with the Jay McShann Orchestra. So, it was clear that jazz music was going to two different places, and Parker’s cerebral, difficult, complex music that was happening in jazz meant that the emotional, earthy quality of early jazz was somewhat deliberately being moved away from. The modern be-boppers were young Black men and women who didn’t want to be associated with the “minstrel show,” ”Uncle Tom” attitudes toward the music of their past, which means they lost a little of the emotional intensity that the people who followed Illinois Jacquet built on. So, that’s why 1942 is so important.

photos by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Louis Jordan, 1946

.

Illinois Jacquet, 1947

JJM The two major figures of early small group swing – Jacquet and the bandleader Louis Jordan – were quite different from one another…

TR Yes, they were very different. Jordan was consciously recreating the sound of the big bands, especially Chick Webb, who he had played with. At the same time, they were both communicating in a deeply emotional way – Jordan would do so with a lot of humor. And even with their different styles, they were both important in the development of this new kind of music.

JJM As you mentioned, Jordan came out of Chick Webb’s big band and was successful in creating that sound and excitement with a smaller group…

TR And it was very popular. He was competing with the Andrews Sisters and Harry James and other big entertainers, and was doing so successfully. His songs were hits, making all the popular charts. The people who followed Illinois Jacquet – like Roy Milton, and those who got their start on Central Avenue in Los Angeles – were playing for a Black audience, a much smaller audience and they didn’t go much beyond that. Jordan did. His was a popular music, but he was also musically important because he was the one who most successfully recreated the big band sound with a small group.

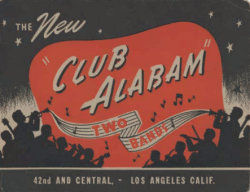

A souvenir photo folder of the Central Avenue (Los Angeles) Club Alabam, and photo of patrons within it; date unknown. [From Jeff Gold‘s book Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s]

.

JJM What areas of the country were crucial to the development of small group swing?

TR Most crucial was Los Angeles, and specifically Central Avenue. The musicians from Los Angeles grew up in a sophisticated urban environment and went to schools that had good music programs, so they really learned about music. Add to this the migration of musicians to California from the Midwest who brought with them the sound that was famously developed in Kansas City, and also within the territory bands of Oklahoma and Texas. So, those two sounds came together – the somewhat sophisticated music that was taught in schools and played by Los Angeles natives, and the earthy, bluesy sounds of the Midwest and Southwest emigres.

The other thing to remember is that nobody really cared about the music being created in California because New York was the center of the music, and it was also where people wrote the music. So, the music of the West Coast developed kind of under the radar. The music coming out of Chicago and Detroit was certainly important, but nothing like the music of Los Angeles.

JJM What did the audience expect from a live small group performance?

TR They expected to dance, and they expected it to be transforming. In my book I write about Jack Kerouac and his book On the Road, where he writes about the experience of listening to this music – “jazz with a beat” – that transports you out of yourself. It is exciting while at the same time it is musically powerful.

JJM And it is a different experience from the bebop of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. A response to the success of what was going on in Los Angeles is that many of the New York bebop musicians turned to hard bop…

TR Right, but hard bop was also a response to rock’n’roll – a music everyone wanted to dance to – and that was not lost on the hard bop players, who then became the soul jazz players, many of whom came from rhythm and blues.

JJM And their interaction with and influence on rock’n’roll was enormous, and that had an impact on the way jazz critics and bebop musicians viewed their style…

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Red Prysock in the late 1940’s

TR Yes, in a variety of ways, and many of them negative. It is important to remember how much the jazz critics hated rock’n’roll. So, the music that guys like Roy Milton and Joe Liggins and Red Prysock were making was already going unnoticed by the critics, but when they started bumping into rock’n’roll, critics began putting their work down.

JJM You write about this in the book, that these musicians “simply did not fit the narrative. They weren’t the big swing orchestras, villains or heroes of the narrative, depending on one’s point of view. or somewhere in between. They weren’t the pioneers, the authentic voice of Americana, to be honored as a relic of the past. They weren’t the heralds of a new age in American music, in which jazz was to take its place in the world of high art.”

TR And they weren’t recording in clubs or on labels that the critical establishment listened to. I don’t mean to be putting down the jazz critical establishment – people like Leonard Feather did great work – but they missed this music.

JJM You mention earlier in our conversation about how modern players were concerned about coming across as “Uncle Tom” figures who were playing into Black stereotypes. What kind of a role did race play in the way critics seemingly shut the “jazz with a beat” musicians out?

TR Guys like Charlie Parker were consciously aware that they were not going to fit into the stereotype of the way people expected Black entertainers to behave. That doesn’t mean they didn’t respect the music. When Charlie Parker was touring, or when he was in the South, the audience would ask for him to play some blues, music they could dance to, and he would do that. So, I don’t want to make too much of this, but I believe that the critical establishment unfairly rejected this kind of music. If you read Leonard Feather’s Encyclopedia of Jazz, none of these people are in it. They are not part of the jazz horizon at all. Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson is there, but the likes of Joe Liggins, Roy Milton, Big Jay McNeely and Red Prysock are not.

JJM Some musicians felt equally at home playing traditional swing forms, the modern form and what you refer to as “jazz with a beat.” People like Ike Quebec, Johnny Griffin, Arnett Cobb are examples…

TR And don’t forget that Ornette Coleman started off playing rhythm and blues…

JJM Right. And swing and modernist musicians like Zoot Sims and Don Byas and Coleman Hawkins were also quite comfortable playing “jazz with a beat.”

TR Yes. In the early 1960’s, Prestige Records created a small label – Swingville – that recorded Coleman Hawkins and other swing musicians, but the music that they played is interesting because they weren’t reproducing what they did in the 1930s. Music is music.

The thing about small group music – “jazz with a beat” – isn’t that it was so much different than what the modern jazz musicians and swing musicians were still playing, it is that it didn’t get recognized. And even now, when I do interviews or talk to people, I say that yes, that music is important for it being a link between jazz and rock’n’roll, but that is not why it is so important. It’s important because it’s great music.

.

A video interlude…Watch a 1983 performance of Big Jay McNeely

.

JJM A central character in your book, and one the critics had an especially hard time with was the saxophonist Big Jay McNeely, whose on stage theatrics included walking the bar and playing while laying on his back, and who you describe as having “a tendency to sacrifice musicality for theatricality.” What were the excesses of the R&B saxophone that the critics felt compelled to push back against?

Montreal Concert Poster Archive/via Wikimedia Commons

Earl Bostic in 1961

TR The critics didn’t like the honking sound by Illinois Jacquet on his “Flying Home” saxophone solo, and they also didn’t like it played at such a high register. One thing that surprised me that I had no idea about until I started doing the research was that many musicians considered Earl Bostic, technically, to be the greatest alto sax player who ever lived. Among other things, he could play perfect, beautiful tones in a higher register than anyone else. In terms of performance, as you said, some would play the saxophone while laying on their back. Illinois Jacquet never did that, but Big Jay McNeely did. His was like a vaudeville performance – laying on his back, walking along the bar. It was a wonderful performance.

In his excellent book Pearl Harbor Jazz, the author Peter Townsend points out that gradually, during the 1940’s and 1950s, the movie critics began to realize that people like Howard Hawkes and John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were great artists, but the music critics never realized that the likes of Joe Liggins or Red Prysock were great artists. He felt that the critics never realized that serious art doesn’t have to be “serious.” And that is what happened. Over time, rhythm and blues became recognized as an important part of American music. It’s Americana, it’s roots, etc. – but it’s still not “jazz.” But “jazz with a beat” is jazz.

JJM Some record companies embraced this music, one example being Atlantic Records, which was a major player in producing small groups. What was their formula for success?

TR Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun were incredibly sophisticated guys. Their father was the Turkish Ambassador to the United States when they moved to New York from Turkey. There is a great story about when they were scouting out Ruth Brown for the label. She was singing in a club when they and Jerry Wexler approached her and told her they wanted to hire her to sing on their new blues label. She asked why they would want to hire her because she doesn’t sing the blues, and in fact she hates the blues. They proceeded to explain to her that they were creating an entirely new kind of blues. And they did. The music was from the South, but it was very much a New York music.

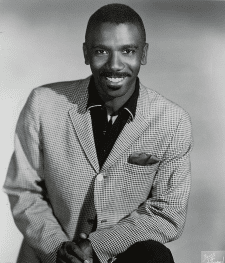

King Curtis, 1971

Atlantic also signed rock’n’roll singing groups like The Clovers, and hired jazz musicians like the drummer Connie Kay to play drums on many of their recordings. King Curtis was on their label and became so important, and it was hard to ignore him as a jazz musician because he was so creative. He came out of the small group swing tradition, but his records were not reviewed in jazz publications like Downbeat. He played modern jazz with deep rhythm and blues roots, and his sound was a New York sound – it couldn’t have happened in Detroit, or Memphis, or New Orleans, or Los Angeles.

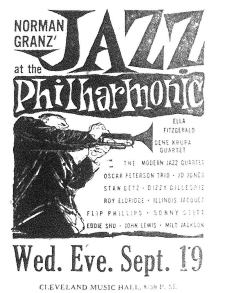

JJM Another executive key to this story was the impresario and Verve Records founder Norman Granz…

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Norman Granz, 1947

.

Advertisement for a 1956 Cleveland performance of Norman Granz’ Jazz at the Philharmonic

TR Yes, he is a little bit of a surprise because you think of him in the 1970’s and 1980’s recording sophisticated music for Verve with people like Oscar Peterson and Sarah Vaughan, but he was in Los Angeles at the beginning, when Illinois Jacquet was just getting started. It was at the time of the Zoot Suit Riots, and Granz had a jam session at his house as a benefit to assist the Latino kids who had been arrested. This gathering turned out to be the beginning of “Jazz at the Philharmonic,” which was a boundary breaker. Imagine, the likes of Big Jay McNeely and Lester Young and Illinois Jacquet and Charlie Parker and Ella Fitzgerald all up on the stage at the same time.

And the crowd loved these performances – they couldn’t get enough of them. Nobody felt restrained. While Jacquet didn’t play on his back like McNeely, he played flamboyantly for the crowd. He was a showman – a dancer as well as a musician. Jazz at the Philharmonic was popular because it had these advanced sounds that were so exciting, played by musicians who played for the people. So, Norman Granz is seriously important to this story.

JJM You brought up Bob Weinstock’s label Prestige a little earlier. He had quite a reputation with musicians…

TR Yes, a mixed reputation – many complained about not getting paid, and others thought he was great. Miles Davis, in his autobiography, complains about Weinstock not paying enough, but he gives him a lot of credit for taking a chance on him when no one else would, and letting him play the music he wanted to play.

JJM You describe Weinstock as “one of the first of the card carrying members of the jazz establishment who recognized rhythm and blues as a form of jazz.”

TR Yes, he signed Willis Jackson in 1960 when soul jazz started happening, and he set up his new label, Tru-Sound, primarily to highlight what he called “contemporary rhythm and blues.” He wasn’t exactly in the forefront of the recognition of small group swing, but he is important.

JJM The organ became a critical instrument of small group swing…

TR Yes, Wild Bill Davis and Bill Doggett started playing the organ in the mid-1950’s, and later that decade Jimmy Smith came along and he transformed the instrument. After him, there were so many great organists – Brother Jack McDuff, Johnny Hammond Smith, and Larry Young among them. But you didn’t really hear much organ until Doggett’s “Honky Tonk,” which was a big hit in 1956. After that it became a huge part of small group swing.

One of the reasons the organ became so important was economics. The musicians figured out that an organ could do the job of a piano player and a bass player, so you didn’t need two musicians, and you could save two salaries. But the other reason was it had a funky sound that people loved.

Jimmy Smith, 195

JJM And Jimmy Smith was one of those players who could appeal to the modernists as well as the rhythm and blues listeners…

TR Yes, he and Cannonball Adderley made it so there weren’t “two sides” anymore. It was jazz that could be danced to, and jazz fans loved it. Downbeat was now even reviewing their albums. That’s why I end my book at 1960 – not because the music ended, but because the perception of it changed.

JJM You wrote, “So this new musical era was good for the musicians of small group swing (and even for some progressive jazz musicians) because it gave them work, but it was not so good in that any hope they had of being recognized as serious musicians was gone, beyond redemption.”

TR That’s because the jazz critical establishment hated rock’n’roll so much. Joe Goldberg wrote a terrific book, Jazz Masters of the Fifties, that includes Ray Charles, which was unheard of. Goldberg points out that, in the 1950’s, if somebody called the disc jockey Symphony Sid and asked for him to play a Ray Charles record, they would be put down and told, “We don’t play that stuff!”

So, it was guys like Ray Charles and Jimmy Smith and Cannonball Adderley who broke the mold. They didn’t break the mold completely, and that is why I feel my book is so important, because to this day people think of artists like Johnny Griffin as someone who played “jazz” and “rhythm and blues.” No, Johnny Griffin played jazz, some of which was rhythm and blues. To this day, he is still not taken very seriously, because jazz critics couldn’t stand anything they felt wasn’t “serious.” As a result, these musicians never got the credit they deserved.

JJM Can you point readers to five essential small group swing recordings?

TR You’d have start with Lionel Hampton’s “Flying Home,” the 1942 recording with the Illinois Jacquet solo. In addition to that, Joe Liggins’ “The Honeydripper” was the first big small group swing hit record.

[NightTrain International]

.

.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Camille Howard, the amazing piano player with Roy Milton’s band, and later on her own. I’ll highlight “X-Temporaneous Boogie,” released under her own name.

[Universal Music Group]

.

.

Paul Williams’s “The Hucklebuck,” based on the Charlie Parker riff from “Now’s the Time,” is a marriage of bebop and small group swing, and it’s not a shotgun wedding – it’s a successful record, and it was a monster hit.

[Universal Music Group]

.

.

King Curtis has a recording of “Birth of the Blues” made in 1958 that wasn’t the big hit record that these others were, but blows me away every time I hear it.

[Rhino/Atlantic]

.

.

For a fifth, and the “jazz with a beat” sound of the Fifties, I won’t say Bill Doggett’s “Honky Tonk,” although it is essential, because everyone knows it. Instead, I’ll choose “Hand Clappin” by Red Prysock. Three minutes of wailing guaranteed to get you up and out of your seat. A lot of disc jockeys, including Alan Freed, used it as a theme song.

[Universal Music Group]

.

.

I’ve also created a YouTube channel which has all the recordings I discuss in the book, chapter by chapter. Great to listen to as you read. (You can access it by clicking here.

.

.

___

.

.

Jazz With a Beat: Small Group Swing, 1940 – 1960

Jazz With a Beat: Small Group Swing, 1940 – 1960

by Tad Richards

.

Click here to read the introduction to the book

Click here to read Tad Richards’ essay, “Jazz and American Poetry”

.

.

___

.

.

About the author

Tad Richards is a prolific visual artist, poet, novelist, and nonfiction writer who has been active for over for decades. He is the author (with Melvin B. Shestack) of The New Country Music Encyclopedia, among many books. He lives in Kingston, New York.

.

.

A sampling of acclaim for the book

.

“Writers and critics too often place music in style cubicles, partitioned off from the sounds around them. Only trouble is, artists rarely work that way. They have an open floor plan, and they mingle constantly. Tad Richards reaffirms that truth with a welcome dive into the under-explored and under-appreciated small swing combos and artists of the ’40s and ’50s, who made music from bebop to rhythm and blues. Richards finishes the book with a suggested soundtrack, which clinches his argument that if these artists are sometimes tough to categorize, they’re always a pleasure to hear.”

– David Hinckley, former pop culture columnist, New York Daily News

.

“This is one of those books that we-jazz critics, jazz historians, jazz audiences, jazz musicians-have long needed. For a long time, these kinds of musical offshoots of jazz have been consigned by jazz people to mere footnotes in music history, but for the musicians who played this hybrid music called, in many cases, rhythm and blues, it was a living and it was life at a different, alternative, musical level. For audiences it was dance and fun and, later, nostalgia, a way of reliving the days when black popular music was a social thing in a much different way than ‘modern’ jazz was, for audiences of all colors and backgrounds. It is not that this kind of music has not been written about, but that few authors have had enough of a jazz background to fully understand the form and the context, as an offshoot of improvised music that was very rooted, not only in the black community, but in a concept of black entertainment that extended back to the early part of the twentieth century. It is well-researched and well-written, a rare book that shows both musical and social understanding and never sacrifices one for the other.”

– Allen Lowe, musician and author of Turn Me Loose White Man: Or: Appropriating Culture: How to Listen to American Music 1900-1960 and That Devilin’ Tune: A Jazz History, 1900-1950

.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview was conducted on February 19, 2024, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

photo by Rhonda Dorsett

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.