.

.

.

.

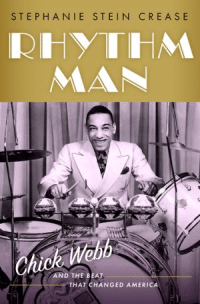

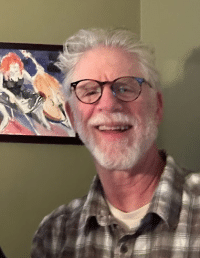

Stephanie Stein Crease, author of Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America

.

.

___

.

.

…..It is easy to romanticize the Swing Era (generally considered to be 1933 – 1947), when the sound of big band jazz was America’s popular music. While economic hardship and war were at the heart of the Era, images of grand ballrooms filled with hundreds of lively couples dancing to the new sounds make it clear that jazz served as balm to it.

…..The bands of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Benny Goodman, and Glenn Miller commonly come to mind when considering the giants of this time in music, but the most influential musician to those who mattered – the dancers – was the drummer Chick Webb and His Orchestra.

…..Born in Baltimore in 1905, Webb moved to Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance and, despite the chronic spinal tuberculosis that left him four feet tall and with a hump on his back, became a virtuoso jazz drummer and innovative bandleader eventually named the “Savoy King” due to his reign at the world-famous Savoy Ballroom. In his short time in the spotlight (he died in 1939), Webb helped create the popular dance and music culture that left an indelible impact on American culture, and his creativity, charisma and persistence enabled him to navigate the harsh realities of racism and show business. Along the way, he became the most eminent drummer of the Era, while lifting others to great stardom – most notably Ella Fitzgerald, who joined Webb’s band in 1935 soon after winning an Amateur Night contest at the Apollo Theater.

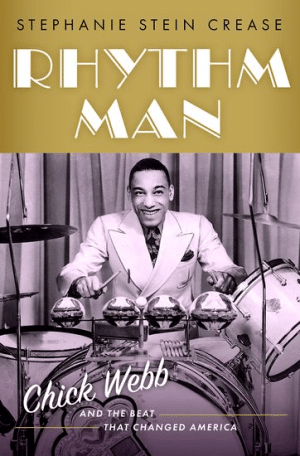

…..Despite his eminent stature as a Swing Era musician, Stephanie Stein Crease – who has, among her credits, written an acclaimed biography on Gil Evans – is the first to fully tell Webb’s story in her newly published biography, Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America [Oxford University Press]. This detailed, intelligent, and wonderfully entertaining book traces Webb’s fascinating life story, and demonstrates how his skills and innovations as a bandleader helped catalyze the music of the Swing Era and the growing big band industry.

…..In a April 19, 2023 interview, Ms. Crease talks with me about her book and Chick Webb, once at the center of America’s popular music, and among the most influential musicians in jazz history.

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

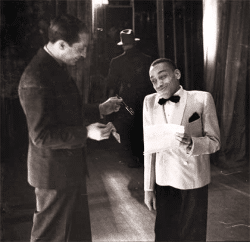

photographer unknown

Chick Webb

.

“Webb’s story, like that of Fitzgerald and many other legendary Black musicians, is that of a resilient person whose persistence, creativity, and entrepreneurism enabled him to navigate his way from his family’s working class roots in East Baltimore through the harsh realities of racism and show business. His life was cut short when chronic illness finally overcame him at age thirty- four. He died in June of 1939 in the beginning of an East Coast tour, at the peak of his band’s success. By then his dreams as a bandleader— national recognition for him, Ella, and his musicians, most of whom had been with him since leaner times— had been realized.”

-Stephanie Stein Crease

.

Listen to the 1934 recording of Chick Webb’s Savoy Orchestra playing Edgar Sampson’s composition, “Stomping at the Savoy”

.

.

___

.

.

JJM What was your first experience hearing Chick Webb?

SSC Years ago, as a jazz journalist, I covered a dance presented by the New York Swing Dance Society, that featured a big band led by Loren Schoenberg performing the music of Chick Webb, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and others. It was a revelation to hear that music live, and see people dancing to it — legendary Lindy Hoppers Frankie Manning and Norma Miller, then in their 60’s, and new generations of dancers.

Around the same time, I was working on archival jazz reissues, helping to create lavish CD box sets from recordings by Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Jimmie Lunceford, and others. So, I was steeped in the great music of the Swing Era though I was interested in jazz of all eras. My first major biography was about Gil Evans, who started out with his own little swing dance band in California and was very influenced by Ellington, Don Redman’s arrangements for Fletcher Henderson, and Benny Goodman. Working on Rhythm Man was quite a journey, re-entering the times and music of Chick Webb.

JJM Why do you feel that Chick Webb is ripe for a biography?

Chick Webb with Moe Gale, owner of The Savoy Ballroom (from Jeff Kaufman’s 2012 film The Savoy King: Chick Webb and the Music That Changed America)

SSC I couldn’t believe that someone of Webb’s musical importance was drifting into obscurity. When Webb died in 1939, his band featuring Ella Fitzgerald was one of the most popular bands in the country. He interacted with Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and all the top bandleaders and musicians on the scene in the course of his career. I wanted to help bring Chick Webb back to the center of that world.

Rhythm Man is the first comprehensive biography of Chick. Drum historian Chet Falzerano wrote a short biography of Webb, with a focus on drum history and Webb’s equipment. Jeff Kaufman’s documentary The Savoy King was also a terrific resource. But researching Webb’s life was challenging. Unlike other major figures – including Fitzgerald – there were no notebooks or scrapbooks, no “special collections.” I did a lot of digging to see what source materials were available, including material about his other musicians, like Fitzgerald, whom Webb hired when she was an unknown teenager. I poured through oral histories and interviews with musicians who had interacted with Webb, including Russell Procope, Mario Bauza, Cozy Cole, Mary Lou Williams, Jo Jones, and many others. That helped bring this book to life.

JJM In addition to these mini-biographies you write of people like Ella, you also write about places. You write wonderfully about Baltimore, where Chick spent his childhood, and a city where Eubie Blake, Billie Holiday, and Cab and Blanche Calloway were also from. What was the musical environment in Baltimore like at that time?

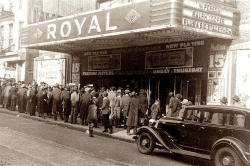

The Royal Theater, Baltimore

SSC That was a very important part of my research. Chick was born in 1905, and while he grew up, Baltimore had a vibrant Black musical community and was an important ragtime center. There were dance halls and theaters on and around Pennsylvania Avenue, which became one of the city’s prime musical hubs. Pennsylvania Avenue was home to the Royal Theatre, Baltimore’s premiere venue for Black entertainment.

Baltimore had several popular early jazz and dance bands. They played music that was ragtime-based, similar to what Eubie Blake would have played but with six or seven musicians. Webb played in those kinds of ensembles, which would have been a good apprenticeship.

JJM There were a lot of stories regarding Chick’s health challenges. When was he properly diagnosed, and with what?

SSC It was difficult to obtain medical documents from Webb’s childhood. Anecdotally, Chick injured his spine as a toddler, when he fell down the stairs rushing to greet his grandfather. He contracted tuberculosis as a child, which led to spinal tuberculosis, a much rarer form of the disease. Tuberculosis was rampant in Baltimore at that time, as it was in many big cities.

Spinal tuberculosis can be a crippling disease for children; it affects spinal growth and can cause deformities like a “hunched” back, which was true for Webb, who was only about four feet tall. He was treated as a youngster and later on by Dr. Ralph J. Young, a pioneering Black physician who helped run a clinic in East Baltimore, Webb’s neighborhood.

JJM How did this disability affect his childhood?

SSC A distant cousin of Webb’s said he was bullied and teased for his appearance, and didn’t attend school regularly. But Webb was an active child, and well-known around the neighborhood. He started selling newspapers to earn money when he was around ten.

He grew up with his mother, two sisters, and a close-knit extended family. Again, anecdotally, people said that his doctor encouraged Webb to play drums to strengthen his spine. Whether that’s true or not, Webb was one of those kids who drove everybody crazy drumming on pots and pans, garbage cans, fenceposts, and so on. He saved enough money selling newspapers to buy a used drum set, and started busking on the street. His step-grandfather encouraged his musicianship, and helped carry his drums around to gigs when Webb started playing with little dance bands as a young teenager.

JJM Chick left Baltimore for New York when he was about 19-years-old, and one of the fascinating stories in your book is his early friendship with Duke Ellington. How did Ellington impact Chick after he arrived in Harlem?

photo via Wikimedia Commons

Duke Ellington, c. 1940

SSC During the mid-1920s Ellington was the leader of the Washingtonians, which was the house band at the Kentucky Club, a basement speak-easy near Times Square. The band was playing some of Ellington’s original tunes, and developed a unique style.

Ellington was also a good businessman, and had been a musical contractor in Washington, D.C. before he moved to New York. He was sometimes approached by other club owners for jobs, and tried to pass them along to his friends. Webb and other young musicians often hung out at the Rhythm Club in Harlem, which was a networking hub for Black musicians looking for work, and hosted jam sessions every night. Chick’s friends included alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, pianist Don Kirkpatrick, and banjoist/guitarist John Trueheart, Webb’s best friend who had moved with him to New York. One day Ellington was offered a job at a new club, but didn’t want it. He and Sonny Greer went to the Rhythm Club, and Webb and Hodges were there. Duke knew that they rehearsed together and had played a few jobs together, so Ellington asked Webb if he wanted to be bandleader for this club. Webb said “yes,” and this was the beginning of Chick Webb’s bandleading career.

JJM They had an interesting relationship. Ellington eventually poached Hodges and Cootie Williams from Chick’s band, and Chick encouraged them to go. Why?

SSC Chick was an incredible talent scout, and like other bandleaders was always looking for musicians who could help his band stand out. New York’s music scene was competitive in the mid-to-late 1920’s, and still is. There were actually only a few bands with steady residencies, notably Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra at Roseland Ballroom, which was a well-paid gig, playing alternate sets with a white orchestra.

Webb’s band’s first job as a bandleader only lasted a couple of months. By 1927, the group—with seven or eight players —was known as Chick Webb and His Harlem Stompers. They started getting a little following in Harlem, but work was spotty. Chick was passionate and inspiring, and kept up with the latest musical trends. His musicians really loved playing with him, but as one of them said, “You can’t pay the rent playing in Chick Webb’s band.” If someone had a better opportunity, Webb wouldn’t hold him back. That was true for Johnny Hodges, who joined Duke’s band in mid-1928, and for Cootie Williams, who came into Webb’s group after Hodges left and joined Duke a bit later. But they were such tight friends with Webb that they were reluctant to leave.

JJM And the pay structure at the Savoy, where Chick played, was different than at some of the other places, so the money was also better elsewhere…

SSC It was not necessarily different, but the Savoy management would rarely pay more than the Musician’s Local 802 minimum wage for dance jobs. In the 1930’s, that was about $33 per musician per week. Eventually Webb earned more as a bandleader and recording artist, and his main soloists got higher pay, too, which was typical of other bands. Chick’s band didn’t really become the main resident band at the Savoy until the early 1930’s. He and musicians were lucky to have fairly steady pay as the country was moving into the worst years of the Great Depression.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1939 recording of Chick Webb and His Orchestra performing “Lindy Hoppers Delight”

.

JJM “Battles of the Bands” were prevalent at the Savoy and other venues in those years. How did these “battles” originate?

SSC There have been “Battles of Music,” or band battles, since the early 20th century and even earlier. Eubie Blake described ragtime pianists’ “cutting contests” in those years. The Savoy Ballroom started presenting “Battles of Music” within a year of its opening in 1926. This was good marketing —having several top bands at the same time, and it was a great attraction for dancers. It’s crucial to realize how interwoven Webb’s band’s success was with its appeal to the Savoy’s dancing audience. The Savoy was founded in the pre-swing era, when dances like the Charleston, the Foxtrot, and stomp music were popular. That’s why Chick called his band the Harlem Stompers.

Webb and his Stompers took part in some of the Savoy’s first “Battles of Music,” and held their own competing with more famous bands such as King Oliver’s and Fletcher Henderson’s. Webb relished these events. According to his sidemen, he would prepare for them like they were “prizefights.” His band played against Henderson’s and Ellington’s several times, but these battles didn’t get the huge publicity of Webb’s later battles with Benny Goodman and Count Basie, in 1937 and 1938.

JJM Chick had a special connection with the Lindy Hoppers. Why was he so popular with these dancers?

SSC The evolution of the Lindy Hop, named for Charles Lindbergh’s solo cross-Atlantic flight in 1927, coincided with the music. Both had a forward momentum that Webb was onto from the beginning. The Lindy was no passing fad — it was intrinsically tied to Black culture, and had a spirit of innovation and improvisation and perfectly matched what Webb and his band were developing in those years. Ellington once said, “Chick was a dancer-drummer who could paint pictures with his drums.”

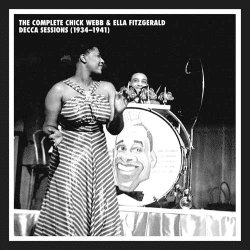

The cover of Mosaic Records’ The Complete Chick Webb & Ella Fitzgerald Decca Sessions (1934 – 1941)

JJM What were the circumstances leading to Ella’s entrée into Chick’s band?

SSC Ella Fitzgerald won the Amateur Night contest at the Apollo Theater in November, 1934. The Apollo contest had just started a few months earlier, and there were amateur contests at other clubs and theaters, too. Many musicians and entertainers got their start that way.

Fitzgerald grew up in Yonkers, and her mother encouraged her to enter local talent shows as a dancer and singer. When she entered the Apollo contest, she wasn’t a total novice, but this was a completely different situation! Ella had planned to perform a dance routine, but she froze up, and ended up singing instead. Benny Carter, whose band was the stage band that night, heard her and was really struck by her voice. He mentioned her to Fletcher Henderson and to Webb, neither of whom showed any interest.

A few months later, Fitzgerald got her overdue “prize” for winning the Apollo contest: singing with Tiny Bradshaw’s band at the nearby Harlem Opera House, which was run by the same people. Bardu Ali, Chick’s M.C. at the time, heard her and was really impressed. He kept bugging Webb to listen to her sing. Webb finally did, and agreed to give her a try-out at a fraternity dance coming up at Yale University. By this time, Chick’s career was definitely on the way up.

Fitzgerald got over beautifully at the Yale dance, so Webb let her start singing with the band at the Savoy. Again, she won people over with her appealing voice and unpretentious manner, and Webb hired her in spring, 1935. So, contrary to persistent myths about both Webb and Fitzgerald, Webb did not hear her at the Apollo contest, nor did he hire her on the spot.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1935 recording of Ella Fitzgerald singing “I’ll Chase the Blues Away,” with Chick Webb and His Orchestra [Universal Music Group]

.

JJM She brought a level of complexity into the band that didn’t exist before that must have been difficult for Chick to navigate. For example, some white critics didn’t like the direction the band was going once Ella joined – although it didn’t appear to impact the Black audience at all…

SSC When Fitzgerald came into Webb’s band, he didn’t have any arrangements for her, so Edgar Sampson and others worked up some charts. After her records and broadcasts with the band started getting attention, song publishers came after them. In 1936, Webb hired a young unknown arranger named Al Feldman — later known as Van Alexander —to write her arrangements.

It’s still so remarkable to think about how lucky Fitzgerald was — to develop her voice and style with Webb and his band, which had a strong identity, and was such was a hit with the Savoy’s dancers. At that time, there were only a handful of female singers working in that kind of setting. Her developing style really fit what the band was doing. But Chick was always aiming for a hit record, one that would elevate his band across the country. So when the band scored hits featuring Fitzgerald— novelty songs like “Mr. Paganini” and “A- Tisket, A- Tasket,” and pop ballads – some critics, notably John Hammond, accused Webb of “going commercial.” Meanwhile, on the bandstand, Webb’s soloists had more freedom than on three-minute records. Recordings from the band’s live broadcast recordings show how thrilling this band was. Audiences loved them, and they broke through all kinds of barriers.

JJM One of the most famous stories in jazz history is the May, 1937 Battle of the Bands event that took place at the Savoy Ballroom between Chick’s band and Benny Goodman’s…

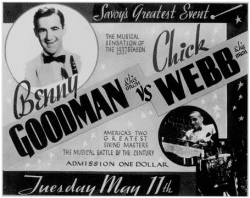

The poster announcing the May 11, 1937 Benny Goodman vs. Chick Webb “Battle of the Bands” at the Savoy Ballroom.

SSC Helen Oakley (who later married jazz author Stanley Dance), was the force behind this, as well as the Webb-Basie Battle of January 1938. Oakley had moved from Chicago to New York to do public relations work for Irving Mills, Ellington’s manager. She was a pioneering woman in jazz— as concert promoter, record producer and journalist, and she ended up producing several stunning small band records for Irving Mill’s Variety record label. On the side, she did publicity for musicians she cared about, and Chick Webb became one of them. She’d heard Webb’s band at the Savoy, and he played drums on some of her Variety sessions. She wanted to help him get more visibility, and she knew that a “battle” between Webb’s band and Benny Goodman’s, then the most popular white band in the country, would get plenty of attention.

The event got polarized in the press quickly— “Who’s the best white band?” “Who’s the best Black band?” “Webb is the rightful King of Swing, not Goodman,” etc. Chick wasn’t going to let Benny win this battle. He rehearsed the band intensely and strategically programmed the set lists. Everyone who was there thought it was one of the most thrilling experiences they’d ever had. The audience was the ultimate winner!

JJM True, but as we know, Chick officially won. And there are many terrific stories surrounding this event, one of which involved Chick and his concern that someone from Goodman’s band was potentially spying on his band while they were in rehearsal, so Chick would deliberately slow the tempo down so as not to give away their hand on what and how they will be playing…

SSC Yes, but Webb did that with other bands, too. He was friendly with Fletcher Henderson’s brother Horace, who did a lot of arrangements for Fletcher in the early 1930’s. Chick managed to get hold of Fletcher’s arrangements, and at their “battles” would play them before Fletcher did!

JJM Chick died in June, 1939, at the age of 34. What were the circumstances leading to his death?

SSC The chronic effects from tuberculosis affected Webb’s other organs, especially his kidneys. This was exacerbated by the band’s insane schedule in the last two years of his life. They were constantly touring, often doing several stage shows a days, and making special appearances. The press reported instances when Webb had to go to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, but he recovered and bounced back several times.

It was heartbreaking hearing his sidemen’s oral histories about this. Sometimes Webb’s aide would have to carry him off the stage after a show. In 1938-39, the band often traveled with another drummer, including famous drummers like Big Sid Catlett and Kaiser Marshall, who went on the road with Webb’s band on its last tour.

In May 1939, a few weeks before his death, Webb’s orchestra was performing on weekends at the Southland Cafe in Boston, and you can hear recordings of the band’s broadcasts from there. His drumming is unbelievable! In one, he plays an uptempo swing version of “Stars and Stripes Forever,” and people on the dance floor are screaming wildly, and members of the band are shouting, “Go Chick!” You would never imagine that he was really ill.

In early June, 1939 the band headed off on a tour down the East Coast, and while they were in Washington D.C, Webb had to return to Johns Hopkins. He sent the band on without him. A few days later, the band was playing for a dance in Montgomery, Alabama when they learned of Chick’s passing. They were devastated and went back to Baltimore, driving all night. Some of the musicians really thought that Chick would bounce back, like he had before.

JJM Chick gave so much of himself on the bandstand, and his story really is a great “American” story in so many ways. He still endures. You quote the legendary drummer Max Roach as saying this about Chick: “I would say that Webb was the [Art] Tatum of the drums. As a musician and instrumentalist, what he did was paramount. It took him above, he created a design and form. . . . Mr. Webb was here to show us a cornerstone, to be involved in what we are doing with jazz. If it hadn’t been for him, there would be no me.” That really is his legacy, isn’t it?

SSC Yes, he was beloved. His funeral was the biggest funeral that Baltimore had ever seen. There are photographs showing thousands of people flocking to the church his family attended in East Baltimore. The church overflowed with people, and there were hundreds of others on rooftops, and standing on top of cars and lampposts. It was a major event that people talked about for years.

In addition to his musical legacy, Webb was also a community- minded person. The Savoy was not only a great place for music and dancing, it was a central place for fundraisers during the Depression—for hunger relief, unemployment, and for social justice events like the Scottsboro Boys’ Defense Fund. Webb and his band performed for many of these at the Savoy, and also in Baltimore and other places. They helped raise money for children’s hospital funds and summer camps.

One of Webb’s enduring legacies is the Chick Webb Memorial Recreation Center in East Baltimore, which is now being renovated, and will include exhibit panels about Webb’s life and career and the Center’s history. Webb and his long-time physician Dr. Ralph J. Young had discussed building a youth center because there was nothing like that in East Baltimore. Webb was planning a series of concerts to help kick off funding for it a few months before he died. Dr. Young carried that vision forward, and held a star-studded benefit in Baltimore in 1940 with Fitzgerald, the heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, and others. This year is the 75th anniversary of the center’s opening, and the groundbreaking for the renovation took place just recently. This is a new milestone for the city, and for Chick Webb.

Webb’s musical legacy is far-reaching. In addition to Ella Fitzgerald’s long and wondrous career, other musicians Webb hired early on have also left a big imprint. They include trumpet player Mario Bauza, a force with Dizzy Gillespie in creating Afro-Cuban jazz fusion, and Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, whose hits helped jump-start rhythm and blues, and rock and roll. Webb’s special gift was connecting so many people through his music. It’s no coincidence that his band’s theme song was “Let’s Get Together.”

.

Listen to the 1938 recording of Ella Fitzgerald singing “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” with Chick Webb and His Orchestra [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat That Changed America

by Stephanie Stein Crease

[Oxford University Press]

.

.

Stephanie Stein Crease is a jazz historian, author, editor, and former Senior Jazz Coordinator for the Jazz Arts Program, Manhattan School of Music. In addition to writing Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat that Changed America, she is also the author of Gil Evans: Out of the Cool (ASCAP/Deems Taylor Award), and Duke Ellington: His Life in Jazz.

.

.

Praise for Rhythm Man

.

“Stephanie Stein Crease, author of a previous biography of another elusive but crucial figure in jazz history, the arranger and bandleader Gil Evans, has finally given us a much-needed cradle-to-grave narrative of this most essential of all jazz drummers.”

– Will Friedwald, The New York Sun

.

“The jazz biography of the year! A clear, fast-paced tracking of the rise of virtuoso drummer and bandleader William “Chick” Webb, Crease mobilizes exciting new archival research to reveal the rich cultural history of Black Baltimore and of Harlem itself—when jazz was in vogue up and down the streets of Upper Manhattan and then all over the globe…This critical biography dives deep, offering surprise after surprise. Crease offers fresh vignettes of Webb’s fellow jazz-star Baltimoreans Blanche and Cab Calloway, Eubie Blake, and Billie Holiday. And we learn how a physically challenged man, hump-backed and standing four feet tall, could drive an all-star orchestra from his brightly lit drumkit throne, make a city-block size ballroom bounce under thousands of dancers’ feet, and still play his role as the family man who supported relatives and friends…”

– Robert G. O’Meally, author of Antagonistic Cooperation: Jazz, Collage, Fiction, and the Shaping of African American Culture

.

“Like Andrew Delbanco’s work on Melville, Stephanie Stein Crease’s Rhythm Man is sweeping, probing cultural history not to be mistaken for mere biography. Missing nothing worth knowing, Crease explores the whole world around the drummer and bandleader Chick Webb—the world that made him and the world he remade with his still dazzling, still under-appreciated musical art.”

– David Hajdu, author of Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn and Love for Sale: Pop Music in America

.

“Though he was one of the true kings of the Swing Era, drummer and bandleader Chick Webb has never properly received his due. That wrong has definitively been righted thanks to the groundbreaking research uncovered in Stephanie Crease’s Rhythm Man. In addition to being a world-class researcher, Crease is an expert storyteller with the uncanny ability to make worlds come alive, smartly relying on the words of those who were there to help tell the story. In the process, readers will be transported from the streets of Baltimore to the battles at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem and all places in between, all in incredible detail like no previous telling of Webb’s story. This is a major work and exactly what Webb deserves.”

– Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum and Grammy Award-winning author of Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong

.

“Fiction couldn’t have created a better hero than Chick Webb, and Stephanie Crease is the writer to tell the tale. A Black artist with a disability, in constant pain, Webb let nothing stop his momentum—the modernization of jazz drumming. Deeply researched and lovingly told, Crease places Webb at the center of American popular culture of the Swing Era. A fascinating read.”

– Linda Dahl, author of Morning Glory: A biography of Mary Lou Williams and An Upside-Down Sky

.

“Jazz, above all, is about rhythm, and in this unique biography, Stephanie Crease has taken the time and pulse of Chick Webb’s short but impactful life and made it swing. She is to biographers what Webb was to drummers—a shining light!”

– Loren Schoenberg, Senior Scholar and Founding Director of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem

“Thanks to Stephanie Stein Crease’s new biography of virtuoso drummer Chick Webb, the Baltimore-born band leader and popular music legend, we now have a detailed and nuanced picture of his amazing life.”

– Jacques Kelly, The Baltimore Sun

.

Click here to read the introduction to the book

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on April 19, 2023, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial and ad-free (thank you!)

.

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

My Mother saw Chick Webb in person while she was in high school and the musical experience stayed with her as well as Chick’s drumming and of course his appearance. I think she was amazed at the level of musical excellence as well as his ability to excel under such physical limitations.