.

.

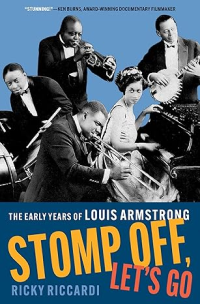

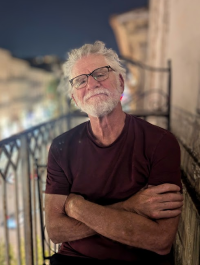

Ricky Riccardi, Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, and the author of three books on Armstrong, including his most recent, Stomp Off, Let’s Go: The Early Years of Louis Armstrong [Oxford University Press]

.

.

___

.

.

…..It is safe to assume we can agree that Louis Armstrong deserved this – a comprehensive biography (now a trilogy) written with expertise, passion, and character worthy of the musician many consider to be the most influential popular music artist of the 20th century.

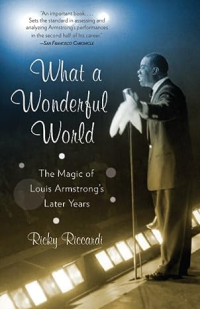

What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years, the first volume in Riccardi’s trilogy, focuses on the final 25 years of Armstrong’s life

…..In 2015, Ricky Riccardi – Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong House Museum – wrote What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years because he felt that period in Armstrong’s life was largely unexplored, and, importantly, not properly appreciated by previous biographers and critics – many of whom considered him to be a buffoonish, unserious musician who relied too heavily on vaudevillian tendencies and “Uncle Tom” antics that disenchanted young audiences. In the book, Riccardi made a clear case for Armstrong’s artistic relevance, and reminded readers of the contributions he made during the turbulent social and political era of 1950s and 60s, including the civil rights movement. The book went a long way toward causing a re-examination of his legacy, while introducing readers to Riccardi as not only a prominent Armstrong historian, but a rising star in the world of musical biography.

.

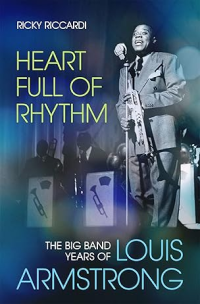

Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong (1929 – 1947), the period during which he became an international popular music star

…..In the 2022 biography, Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong, Riccardi again takes on a period of time when discontent for Armstrong’s work existed throughout much of the critical world. Two prominent examples: Gunther Schuller – though full of praise for Armstrong’s work in the 1920s – complained that Armstrong “did succumb to the sheer weight of his success and its attendant commercial pressures.” Another, Armstrong biographer James Lincoln Collier, lamented “the bitter waste of [Armstrong’s] astonishing talent over the last two-thirds of his career…I cannot think of another American artist who so failed his own talent.” In contrast to this criticism, Riccardi wrote of Armstrong’s courage and eminence, and that he “met popular music head-on, adapting the sounds favored by white listeners, and completely transformed them into something new, something exciting, something Black, something swinging.” The book also cemented Riccardi’s growing reputation as a serious Armstrong historian. Gary Giddins – the most esteemed jazz writer of his generation and himself an Armstrong biographer – wrote that Heart Full of Rhythm “is the best account we have of Armstrong’s vital work with big bands – the research is impeccable, the ardor contagious.”

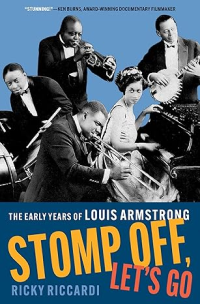

…..In the third book, the newly published Stomp Off, Let’s Go: The Early Years of Louis Armstrong, Riccardi focuses on the most admired stage of Armstrong’s life, his complex childhood and burgeoning musical career, a time critics generally agree when his electrifying music (particularly the “Hot Five” and “Hot Seven” recordings of 1926 – 1928) and unique charismatic appeal inalterably changed the direction of popular music. It is a time once covered splendidly by Armstrong himself as well as by several prominent writers, leaving one to question the need for this book. But since the time those works were published, a copy of Armstrong’s original typewritten manuscript of Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans was donated to the Louis Armstrong House Museum, revealing a wealth of new information. And, when the jazz historian Chris Albertson passed away in 2019, his extensive collection of materials – including those assembled during his time as Armstrong wife and musical collaborator Lil Hardin’s biographer – became available to the Jazz Foundation of America, Riccardi saw the backbone of previously unutilized biographical material he could build a biography around.

…..The result is a comprehensive, expertly written, and always entertaining book that pulls readers into several rich stories: the challenges of a Black family living in the racist American South of the early 20th century, and the many temptations a child had to confront and repel within it; an evolving musical talent who may never have played an instrument seriously had he not occasionally succumbed to those very temptations; a deep mentoring environment that included his oft-absent mother, prostitutes, pimps, bouncers, brilliant musicians and a loving Jewish family who employed and embraced him; a career-altering job on a Mississippi riverboat known to bandmembers as a “conservatory.”; the exhortations of a strong-willed and loving wife who challenged Armstrong to see himself as a distinctive and influential artist who belonged in the first trumpet chair of a band, not the second; a journey to the musical worlds of Chicago and New York that included distinguished work with cutting edge big bands, vaudevillians, and classical music ensembles; and, finally, the formation of the combos known as the Hot Five and Hot Seven that modernized music, the way artists play it, and how audiences interact with it and respond to it.

…..Riccardi has become a major biographer whose work on Armstrong is a supreme achievement, one that the Grammy award-winning jazz musician Jon Batiste describes as “an extremely important chronicle of world history.”

…..In our February 28, 2025 interview, the author discusses this volume of his trilogy, and the great artist once again at the heart of it.

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

photo courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum*

Louis Armstrong’s first smiling publicity photo, found in a scrapbook maintained by Armstrong and Alpha Smith

.

“I remember the first time [trumpeter] Wingy [Manone] took me to see Louis Armstong at the Savoy Ballroom at 47th and South Parkway. I can close my eyes now and still see the crow of admirers carrying Louis Armstrong on their shoulders like a hero from the front door all the way to the bandstand. I would say there were at least two thousand people in the ballroom that night who loved Louis. I never seen as much admiration for any musician as there was for Louie during that period. That was a scene I’ll never forget.”

-pianist Art Hodes on seeing Louis Armstrong – under the band leadership of Carrol Dickerson – at Chicago’s Savoy Ballroom in 1928

.

Listen to the 1926 recording of Louis Armstrong and His Hot Fives play “Heebie Jeebies” – an early example of scat singing., with Armstrong (trumpet, vocal); Johnny St. Cyr (banjo); Lil Armstrong Hardin, (piano); Johnny Dodds (clarinet); and Kid Ory (trombone). [Columbia/Legacy]

.

___

.

JJM Congratulations, Ricky, on writing another important and wonderful book on Louis Armstrong. This is the third in the series, and, interestingly, you ended up writing them in reverse chronological order. Did you intend to write a book about his early years?

RR No, and the funny thing is that now it looks as if that was my plan the whole time, and while I wish I could say that was true, it was never my intent to do a trilogy, and it was definitely not my intent to write it in reverse chronological fashion. But now having done that, I’m very pleased with the results, and I’m also very pleased with the order I wrote them because it actually worked out for the better.

JJM You wrote that you discovered new material about Armstrong. Did that help you make the decision to write this third volume?

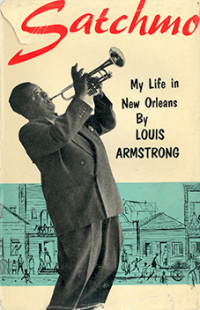

RR It did, yes. If I had started with this book first, maybe 15 or 20 years ago when I was writing my first book, What a Wonderful World, I probably would have just had to rehash Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans and whatever people like Gunther Schiller and Thomas Brothers had already written. A lot of stuff that was already out there and nobody would have really wanted to read yet another version of it. So, at the time I decided that since his later years and his middle years were unexplored, I would start there.

In my day job as director of research collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, we continually get new items donated to our archives. In 2013, the musician and collector Stan King reached out to let us know that he had 16 acetate discs of a conversation Louis had with the editors of the Record Changer magazine in 1950. And while I had read that magazine, this was the raw two-and-a half-hour conversation, and it was almost entirely about New Orleans, Joe Oliver and Bunk Johnson, so it was very cool and important material to add to the archives. Then, in 2016 the son of Louis’ editor at Prentice Hall gave us a copy of the original typewritten manuscript that he typed out for Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans before it was sent it into Prentice Hall, which was great because it is direct from the source. I remember thinking at the time that with that raw document, somebody could do a paragraph-by-paragraph annotated version of Satchmo. And then in 2019 the jazz historian Chris Albertson passed away. He had been working on an unfinished, unpublished autobiography on one of Louis’ wives, the pianist Lil Hardin, and after he died, by some miracle, we were able to access his collection before it went to the dump, which is an entirely different and fascinating story. The Jazz Foundation of America stepped in and rescued it from the dumpster, and we then had one day to go through the collection and take whatever we could. Within it were Lil’s autobiographical chapters and photos from her scrapbook. That’s when I started realizing that these voices from the past were trying to get my attention. Shortly after my second book Heart Full of Rhythm came out in September 2020, my editor asked me if I’d like to finish the trilogy, and with all this new material available to me, I told her I’d like to do it.

Armstrong’s 1954 autobiography

Even during the process of writing it, there were many new things available to research – for example, I got a newspapers.com subscription, an ancestry.com subscription, and an RIPM jazz periodicals subscription that all provided new information that wasn’t there when I wrote my first book. So, I had so much at my fingertips. I then went to New Orleans, where I got access to the collection of the late Tad Jones, who had done 20 years of research on Louis in New Orleans. Then, all of a sudden interviews that the jazz historian Phil Schaap had done with people who saw Louis in New Orleans, on the river boats, and in Chicago became available to me. When I handed in the manuscript, I thought, I’ll be damned, I think there might be something new on every page here, and it wouldn’t have been that way if I had written it 15 years ago.

JJM This material must have included new information about his big band and later years as well…

RR Yes. Fortunately, some of the material started coming in while I was writing the second volume Heart Full of Rhythm, so I can say that I’m still content with that book, and I stand by it. And while I still stand by my first book, What a Wonderful World, it feels like it is a bit out of date because I have 14 years of information I’ve learned from new research. That book has been out of print since 2019, and while I don’t have a piece of paper to wave around and confirm this yet, I am in talks with my editor and my agent about doing a revised, updated edition of What a Wonderful World. Then, the trilogy will be complete again.

JJM Well, you’ve done a marvelous job with telling Armstrong’s story. While reading this particular volume of it I couldn’t help but think this part of his life would make a fabulous film since it exposes so much complexity in his personal life; growing up poor and Black in the American South, the development of jazz music, the river boat he played on, his times in Chicago and New York. I have a feeling you’d agree…

RR Completely. While writing the book there were times it felt as if I were writing a movie script, seeing these relationships with his mother and King Oliver, and events like the cutting contest with Johnny Dunn, his reception in New York with Fletcher Henderson, and characters like Henry Matranga and Black Benny. I could see the cast in my eyes and the climactic scenes that helped me to shape the narrative. I enjoyed discussing the music and his seminal records, but at the heart of it is a human story that needs to be told in just the right way.

JJM Armstrong grew up in extreme poverty in New Orleans, and you get into the depths of it. For starters, his mother was a prostitute who was repeatedly arrested for “disturbing the peace,” his father was mostly absent, and New Orleans was an especially challenging place for a Black family to live. Among all of this, who were the stabilizing influences in his childhood?

RR For the first five years, he was fortunate to live with his grandmother and great-grandmother, and while I can’t say that they spoiled him, they definitely gave him love, and they nurtured him and made him feel pretty special. While he had them, he may have also been wondering where his mother and father were. But, as he said, at some point he was calling his grandmother “Mom” because that’s just how she felt to him.

Courtesy of the Hot Club of New York*

Studio portrait of Louis Armstrong, his mother, Mary Albert, and sist, Beatrice “Mama Lucy” Armstrong, taken by Villard Paddio in New Orleans most likely in late 1919 or early 1920.

But then his mother gets sick. She has a daughter at home and needs help around the house, as well as another paycheck, so she sends for her five-year-old son. And that’s where the story begins, because now he’s living in a one room apartment in a more dangerous neighborhood they called “the battlefield,” becoming somewhat of a street urchin, walking the streets every day and at times getting in trouble while looking for ways to make money.

In terms of stabilizing factors, there was music. The neighborhood was very musical. Armstrong grew up at 1303 Perdido Street and Funky Butt Hall was 1319 Perdido Street, and the bands would often come outside and play a short set to let people know they were about to start. So, he’s hearing music – which is very important to him – but more important was the community. There were people who looked out for him, and he always made sure that they were all remembered. Some of the people who read his second autobiography, Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans, were a little disappointed that there wasn’t more in it about the nuts and bolts of music, like what scales he practiced in or how he learned to improvise. Instead, he devotes page after page to talking about Black Benny and Slippers the bouncer, and naming all these people who were there for him. That was something I wanted to uphold in this book, and write about the people in his community who looked out for him. When his mother would sometimes get arrested and go to jail for 20 or 30 days, where and to whom could he turn when he was alone?

I made it a point to roll up my sleeves and look through newspapers and through census records in hopes of finding anything I could about the lives of the people where were there for him. When a photo was discovered of Black Benny Williams, the bass drummer, I knew that had to be in the book because it was everything Armstrong described about him – a cocky head tilt with a smile, his eyes closed and with a big cigar coming out of his mouth. He was just one example of the people he never wanted to forget. They believed in him. They protected him. They were all struggling, but they saw something in him. It didn’t come easy because he had to work many jobs and many hours. He also got arrested multiple times, and had to run from the police and avoid bullets and knives and prostitutes and everything else. But somehow, when he got on the train to Chicago he was on his way, and he wouldn’t have been able to accomplish any of that without his community.

JJM Of his arrests, the most famous was for shooting off a gun on New Year’s Eve, for which he was sent to the institution known at the time as the “Colored Waif’s Home for Boys.” What life lessons did he learn during his time there that helped shape his life?

RR For the first time since he left his grandmother’s house, he had some stability. They had a daily schedule – they got up at the same time, lined up for inspection, and went to school – and he had a year-and-a-half of solid schooling on an everyday basis, where they taught him the trades and discipline that involved military moves like parade rest and shoulder arms. And then there were the music programs, which is obviously what changed his life.

photo via Louis Armstrong House Museum

Armstrong in the Waif’s Home band

He also witnessed harrowing stuff there – kids who tried to escape were beaten and whipped right in front of all the other kids. He was determined to stay away from the wrong side of the keepers at the Waif’s Home, so any of his “bad boy” tendencies may have dissipated pretty quickly. When he reflected on his time there he said it almost felt like a boys athletic club – they would do things like swim and play baseball, and it became a positive influence. He hated to leave, and even after leaving he continued going back as a guest musician, even helping out with the band. The bass player Chester Zardis remembers him coming in and talking to them and playing some parades with them, but he wasn’t staying there anymore, I think he just liked that atmosphere.

He liked the man who ran the institution, Captain Joseph Jones, and he referred to him and his wife, Manuella as “Mom and Dad.” He also liked the musical director Peter Davis, and after he left he would return to his shack for lessons. So, the Waif’s Home was a very important time for him, but he was the only one who made it out of the home and had an incredible career as a musician. Henry “Kid” Rena became a well-respected cornet player, but I decided to do more research on some of the other kids in the Home. For example, there was Isaac Smoot, who ended up serving time in Sing Sing for being a pickpocket, and his friend Arthur Brooks was shot in the head, murdered at the age of 17.

It is crystal clear that the Waif’s Home had a positive influence on Louis, and thank goodness it was there for him at the time because it showed him that music could be his way out. He took music very seriously, but even with it there was no guarantee that he’d make it into adulthood, or that he’d survive the South, or that he would even become a musician – never mind its most towering and influential figure. He could have fallen into his old habits or gone off with the Waif’s Home crowd and gotten into more trouble. He could have been the one shot in the head. He could have been the one in Sing Sing. So, he did have these lessons and always gave credit where it was due. His grandmother and his mother taught him good common sense, and the Waif’s Home taught him, as his sister put it, “not to be sassy.” He had his head screwed on pretty tight when he left there, and I think that experience helped him navigate New Orleans and the entire world for the rest of his life.

JJM After he got out of the Waif’s Home he worked as a musician for a time at a very colorful club called Matranga’s at night. Can you describe this venue, and was it typical of the kind of place available for Black musicians to perform in?

RR New Orleans gets so romanticized, especially places like the Red Light District, or Storyville as they later called it, but to hear Louis tell it, Matranga’s was just a honky tonk. It was on the corner of Liberty and St. Peter Street, right across the street from where he lived. It had a bar, and gambling in the back room, and the prostitutes would hang out there, as would their pimps. This wasn’t Birdland with a quiet policy or anything like that – they liked to hear the blues and have music in the background. But this is where Louis played for hours and hours – sometimes the jobs would start around eight or nine o’clock at night and he’d occasionally play until four or five o’clock in the morning. People who knew him at that time said he only knew three songs, so it got a little repetitive after a while, and to give his lips a rest he started singing his bawdy variations on the blues.

The French Quarter, c. 1915

Matranga’s was a typical gig for him because he wasn’t able to play in the parades or the funeral marches that were happening all the time. Musicians like Joe Oliver and others of that caliber could play a club like Pete Lalas in the Red Light District, but those opportunities were not yet there for a 16-year-old kid. He had to take what he could get. At one point he said that playing at Matranga’s felt like Carnegie Hall, and that’s how he treated it. I’m sure many of the blues choruses he taught himself on that stage crept out on records and concert halls in the later part of his career.

JJM When did the musicians of New Orleans begin to sense that Armstrong had the potential to be a great musician?

RR I’m not going to say that Armstrong was a child prodigy or anything like that, but when I was doing research in the oral history section of the 1950’s and 60’s at Tulane University, many of the first generation of jazz musicians’ initial memory of Louis Armstrong was of him playing in parades in the Waif’s Home band. They remembered his tone, and people like Kid Ory would tell him things like “stick with it, young man. You are going to be something one day.” It wasn’t as if he was hitting high C’s and dazzling them all, but he had people like Zutty Singleton remembering that he played a good, strong lead on “Maryland, My Maryland.” The fact that people would still remember that in the late 50s and early 60s indicates they saw his potential.

But it isn’t as if he left the Waif’s Home and became a professional musician – he went right back to his job working on the coal cart and working with the Karnofsky family. It was around 1915 when Black Benny started tying Armstrong to his wrist and bringing him to Kid Ory’s gigs, asking to let Louis sit in. Joe Oliver came along and spent time sitting on the bandstand at Matranga’s with him, which is why Armstrong always gave Oliver the credit for turning him into the musician he became. So, he was still a kid and far from professional status, but I think that the raw materials were there and he just needed a little bit of massaging.

JJM Who taught him to read music?

Agrahamt, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Fate Marable’s band on the S.S. Sidney, c. 1919. Louis Armstrong is fourth from the left

RR He learned how to read while working for Fate Marable’s band on the riverboats, beginning in 1919. The band played arrangements, so it was a reading band. For the first few nights he was in the band, Louis would listen and basically say that he “got it” and would play his part. He obviously couldn’t keep going like that. So, while on the boat going up the Mississippi River the band members’ day times were usually free, and during that time Louis would go upstairs with a multi-instrumentalist by the name of Davy Jones, who took the time to show him how to read. By the end of the three years Louis played in Marable’s band, he had become a well-rounded musician, including having the ability to read. Zutty Singleton would say that getting hired by Fate Marable was like going to the conservatory, and that’s how Louis treated it. Before his experience with Marable, the only formal training was what he learned while at the Waif’s Home.

Armstrong remembered that when he formed his first little band, the Brown Skin Jazz Band with the drummer Joe Lindsay, they would get sheet music of the latest pop tunes, which only of them could read, but that’s all that was needed because they would play it once and memorize all have their parts. But Louis didn’t really know how to count and how to divide the notes or how to phrase them, so he would find Joe Oliver who would always stop to show him how to read the passages. So, he was dabbling with wanting to learn how to read music but didn’t until he was forced to on the river boat, which then set him up to read arrangements in the orchestras of Fletcher Henderson and Carroll Dickerson.

The Sidney of the Streckfus Line, with Captain Streckfus and 405 passengers on board

JJM Reading this part of the book is a reminder of how important his time playing on the riverboat with Fate Marable was to Armstrong, and it also is such a romantic part of American history – the idea of dancing to jazz music at its earliest stage of development on a paddle wheel boat cruising the Mississippi is a delightful image. The music evolved while Armstrong was in the band, not always for the better. Did he have anything to do with the evolution of what was being played on the boat?

RR The people driving the evolution were the Streckfus brothers, who were running the boats. They weren’t performing musicians but they knew music and they really listened for the trends because they wanted their boats to have the latest sounds. Whatever was popular, the bands on the Streckfus Steamers were going to play in those styles. Some historians saw Louis Armstrong and Johnny St. Cyr and Baby Dodds and Pops Foster and assumed that they were hired because they were from New Orleans, but Fate Marable hired them because he knew they could play ragtime music. Jazz music had recently been recorded for the first time and Marable wanted the real thing in his band.

But in 1920 the Streckfus’s got excited by another sound – a record by Art Hickman, a drummer out of San Francisco who led a dance band influential to Paul Whiteman, who was also on the west coast. So, imagine Louis Armstrong and all of these great New Orleans musician huddled around the Victrola while listening to Art Hickman play songs like “Avalon” and “Japanese Sandman,” and then to Paul Whiteman play a song like “Whispering.” They learned those arrangements right off the records and then performed them on the Mississippi River, probably with a little bit of New Orleans swing thrown in. We can only imagine what that band sounded like, but it’s an early example of Armstrong embracing the popular sounds of the day while trying to learn something new. And the Streckfus brothers gave him all the credit, saying that he grasped the music immediately, and that when he launched into “Avalon” the boat was rocking with people who had never heard dance music played like that before.

That was during Armstrong’s second season on the boat. During the third, the Streckfus brothers heard about a new thing, “toddle time,” which was four beat dance music. Anyone could dance and bounce around to it, but the New Orleans musicians didn’t like that. The Streckfus brothers were going to get what they wanted – which was whatever trend was popular at the moment – and Louis and the New Orleans musicians went along with it until they decided to go back home.

JJM There are several figures of importance in this volume of Armstrong’s history, one of whom is Joe Oliver. Theirs is a classic mentor/protege relationship – Armstrong emulated everything Oliver did and loved him dearly, to the point that his willingness to be deferential to him stalled his own growth as a musician. When Oliver went to Chicago he originally wanted Henry “Kid” Rena to join him, but he didn’t want to leave New Orleans. George Mitchell was his next choice, not Louis. What was Oliver’s reluctance to hiring Armstrong?

Joe “King” Oliver; c. 1915

RR While doing the research, that was a surprise for me because the romantic story we know is that Oliver summoned little Louis Armstrong to join him in Chicago, but I don’t think Armstrong knew that he wasn’t the first choice. This information came out in later interviews – especially the Tulane interviews. Oliver had a sizable ego, and it’s possible people told him to watch out for this kid in New Orleans, who is an amazing player, and there might have been a part of him felt that the last thing he wanted was for this kid, “little” Louis – who used to run errands for his wife and to whom he gave lessons for 50 cents – to come to Chicago and embarrass him. However, at the same time his chops were fading, he wanted to expand the size of his band, and he did need some help, so Armstrong got the call.

The William Russell Jazz Collection at the Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Clairborne Grima Fund, acc. no. 92-48-L.956.*

Famous studio portrait of Louis Armstrong and Joe Oliver, which, according to Stella Oliver, was taken in St. Louis while Oliver was visiting his protege on the riverboat in the spring of 1921

Oliver had nothing to be afraid of because Armstrong was so deferential. He was never going to play higher or faster than Joe Oliver, and he wasn’t going to cut him or show him up or anything like that. I found several interviews with people who saw him in Oliver’s band at the Lincoln Gardens and they all said that Louis played second all night, with no solos. They would even take their breaks together. To hear Armstrong tell it, he was the happiest guy in the world because he’s up North, he survived New Orleans and now surrounded by musicians from there, and playing in a band led by his father figure. He didn’t feel as if he needed to be the star, and later said that he wished Oliver had given him more solos on the records, not from an ego standpoint, but because he felt more records would have been sold and that Oliver would have received the credit. That’s how far Louis was willing to go – he could have made ten years’ worth of records playing all of his dazzling licks and everything else we now know and love, but the records all would have been under King Oliver’s name. He even mentioned Erskine Hawkins, whose trumpet man Dud Bascomb took the solo on his biggest record, “Tuxedo Junction,” and said he would have done the same thing.

The Lil Hardin Armstrong-Chris Albertson Collection, Louis Armstrong House Museum*

Eighteen-year-old Lillian Hardin in Chicago in 1916, well on her way to becoming “The Hot Miss Lil.”

That’s where the influence of Lil Hardin comes in. If she hadn’t pushed Louis out of his comfort zone he likely would have remained just a happy sideman. She told Louis the story about Oliver telling her that as long as “little” Louis is in the band, he’ll never pass me – I’ll always be the king. When Louis heard this story years later, he blew up at Lil and didn’t speak to her for about ten years after, even though it was the truth. Flash forward to the time when they are playing across the street from one another in Chicago, and Louis is taking Oliver’s crowds away. There is a sad scene in my book’s epilogue where Oliver is selling vegetables along the side of the road in Savannah, Georgia, and they have a teary-eyed reunion. But as much as Louis learned what to do with his life and his career, he also learned what not to do by observing Oliver.

JJM We now know that Lil Hardin – who Louis was married to for several years, including during the time of the Hot Five recordings – had a major influence on his career, and you describe her as an “architect of his stardom.” Did he ever acknowledge to her personally that she held that importance?

RR In August of 1970, near the very end of his life, he recorded an audio letter for the biographer Max Jones, which I quote from several times in the book. He knew his health was failing and that he wasn’t going to be around forever, so I think he wanted to set the record straight while he still could. At one point he says how much he loved Joe Oliver, but Lil had thoughts about how he was holding him back. In the letter he said; “I listened very carefully when Lil told me to always play the lead, to play second trumpet to no one. They don’t come great enough. And she proved it. Yes sir, she proved that she was right, didn’t she? You’re damn right she did.” On that same tape he said that Lil had the right to engineer his career because she heard the preacher say “Love, honor and obey” just like he did. It was in her best interest to help him out. So, he knew her importance and he gave her the credit, and I would say that without Lil pushing him, he would have just been a happy sideman, and I doubt we’d be talking about him in the same way.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the February 26, 1926 recording of “Cornet Chop Suey,” from The Hot Fives [Columbia/Legacy]

.

JJM How did he go about assembling his band for the for the Hot Five recordings?

RR This is one of the more beautiful stories in the book because he finally gets the chance to make a record under his own name. He’d been recording for two years, but always as a sideman to the likes of King Oliver, Fletcher Henderson, Clarence Williams, and with blues singers like Bessie Smith. Along comes Okeh Records who tells him to put together his own band. The only parameters seemed to be that they wanted it to be like the Clarence Williams Blue Five – which they had success with in the early 1920s – so it had to follow the popular ensemble model of trumpet, trombone, clarinet, banjo, and piano model. It was popular and it also recorded well.

Courtesy of the Louis Armstrong House Museum. Photo restoration by Nick Nellow*

1926 publicity photo of the original Hot Five. From left to right: Johnny Dodds, Louis Armstrong, Johnny St. Cyr, Lillian Hardin Armstrong.

Louis knew he was going to play trumpet and that Lil would play the piano, but who does he hire? Kid Ory, his old boss from New Orleans, on trombone; Johnny Dobbs, who was the clarinet player in the Ory band from New Orleans; and Johnny St. Cyr on banjo, who also played with Ory and who also played on the riverboats. These three men were older than him, and they all believed in him early on, so I think it was Louis’ intention to not only pay them back by hiring them, he also wanted to recapture their sounds. It isn’t as if he assembled these musicians in order to break free and dazzle the world with recordings people will talk about for 100 years. All of that happened, of course, but he put these musicians together because it was an opportunity to make records with his old friends from New Orleans who also happened to be elders who helped him when he was a teenager. That’s how the whole thing started, and of course once people heard them, the rest is history.

JJM Of the recordings from the Hot Five sessions, the tunes “Heebie Jeebies” – known for its scat singing origin story – and “West End Blues” understandably get so much attention. What other pieces stand out as revolutionary recordings?

RR February 26, 1926 is such an important date because that is the day he records “Heebie Jeebies,” which revolutionizes jazz singing, putting scat singing on the map. And the very next song he records is “Cornet Chop Suey,” which many of the trumpet players who heard that record said went off like an explosion. People heard his solo, they heard his phrasing, the stop time, the melody, the chorus at the end where he plays a little unaccompanied, diminished lick that he works all over the horn. That piece went a long way to codify a solo, and how to tell a story within it. As revolutionary as that was, he had written the solo out, working in a lot of clarinet figures and a lot of arpeggios.

Another important piece is “Big Butter and Egg Man,” which was recorded in November of 1926. That tune really tells a story, with a beginning, middle and end, working towards a climax – and it’s not just arpeggios or variations, now he is telling a story. “Potato Head Blues” of 1927 is a master of storytelling, as is “Wild Man Blues,” but the funny part is that those songs don’t quite connect with the audiences like the ones from 1926. “Heebie Jeebies” and “Big Butter and Egg Man” were hits that went right into his repertoire, and he had to play them every night just like he had to play “Hello Dolly” every night in the 1960s. They were big, big hits.

As revolutionary as the recordings are, and as much I enjoyed writing about them, I also wrote about Okeh Records and the marketing of the records, experimenting with the Hot Seven sound, returning to the Hot Five ensemble, and bringing in Lonnie Johnson that results in the recordings of “Hotter than That” and “Savoy Blues,” which were the final sides by the original Hot Five. By that point, Louis had outpaced everybody and even Okeh records realized that, so it marked the end of the New Orleans elders band and the beginning of the Earl Hines/Zutty Singleton era that resulted in one revolutionary number after another, from “West End Blues” to “Weather Bird” and everything in between.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1928 recording of “West End Blues,” with Louis Armstrong (trumpet); Earl Hines (piano); Fred Robinson (trombone); Jimmy Strong (clarinet); Mancy Carr (banjo); and Zutty Singleton (drums). [Columbia Jazz Masterpieces]

.

JJM What was the origin of the cadenza to “West End Blues?”

RR I went into this fully confident that I’d figure this out. I found interviews with Earl Hines, Zutty Singleton and Lil Hardin, and they all had different answers but it was obvious that it was something Louis had worked out. He didn’t really talk about it much, and when he did he would say something like, “I had to put an introduction to the song so that’s what I played.” Lil said he got the idea from some of the classical music exercise books she gave him. Zutty Singleton said that they rehearsed it in the front room of his and Lil’s home, so when they went to the studio he knew what he was going to play. Earl Hines was suspect – when he heard Louis play it, he asked him when this becomes a hit, are you going to be able to play that every night?

So, where did it come from? How many takes did it take? Tough to say. It has been held up as this incredible moment of improvisation, but I think it was something that he had been thinking about developing, and as I write in the book, every influence and everything he had heard from Joe Oliver to Enrico Caruso is in every one of those 12 seconds. That solo is like a summary of the first 27 years of his life.

JJM What was the immediate impact on the musical world following the recording of “West End Blues”?

RR It was huge, but I always like to remind people that the Hot Five recordings were still “race” records. “West End Blues” didn’t sell as much as a Paul Whiteman or Guy Lombardo record, but musicians heard it. In the book I quote Hoagy Carmichael, Teddy Wilson, Billie Holiday, Leonard Feather – singers, piano players, composers, and critics who all heard this record – and they remembered every note of it. That alone was huge. And then Louis added it to his repertoire, so now he’s playing it at the Savoy Ballroom every night and the audience would sing and scream along with him.

The song had a major impact, and it became one of the biggest selling records for Okeh, and I think it’s the one that convinced the head of the label Tommy Rockwell that this Armstrong guy has something different, and that if he could reach the average white audience they’d respond favorably to him. So, the ironic thing is that “West End Blues” – which is held up as the greatest jazz classic of them all, with its unaccompanied cadenza and the scat thing in the middle and the high notes at the end – is the Armstrong song that breaks through. In his effort to keep Armstrong in front of that audience, Rockwell had him record Tin Pan Alley songs, so by 1929 he’s making

Bonafide pop records like “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love,” and “When You’re Smiling” and “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and everything that follows. And it works, and he becomes the first Black pop star. So, although people always said they wanted more “West End Blues,” just when he hits this peak he goes “commercial.” “West End Blues” opened up a lot of ears and a lot of eyes that he was capable of much more than just playing the blues and playing the trumpet. He was a world class entertainer, singer and star.

An early Lp version of Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five. L to R – Armstrong, Johnny St. Cyr, Johnny Dodds, Kid Ory, and Lil Hardin.

JJM What is the enduring impact of these recordings?

RR It is that they changed the way people sang and the way people played their instruments – and only one guy doing that can’t be found in any previous era. Singer and instrumentalist was already a rare combination to begin with and so few did it beautifully – Nat “King” Cole comes to mind – but to completely change the way people sang and phrased and with scat singing is remarkable. And then you follow that up with how it impacted instrumentalists. By the late 1920s and early 30s, Joe Oliver remakes “West End Blues,” and it sounds like Armstrong’s record. Earl Hines records “Beau Koo Jack” and it sounds like Louis’ record. They’re quoting “Potato Head Blues” on Ted Lewis’s “Crazy About My Baby,” and so many other examples as well. So, suddenly Louis’ improvisation is the language of how to solo, which turns into compositions, which turns into arrangements. That is what I see as being the biggest takeaway from those years.

Going to back to your original question, I think writing this trilogy backwards worked out because for years I had read that 1929 was a jumping off point for Armstrong, the era of supposed great decline when what Gunther Schuller described as “the tentacles of commercialism” began. So, I determined to defiantly dispute that by writing two books dealing with his life after 1929 with the intent of showing readers that there was a lot of great music and many incredible accomplishments during this period that was considered by many to be a waste of talent. But now, by going backwards and writing this book last, it felt like writing the instruction manual on how he became the first Black pop music star. How does he go on to conquer film and television and radio and become Ambassador Satch?” It’s through these years, and it’s one building block at a time. At first it was Bunk Johnson, then Joe Oliver. Then he’s singing with the Karnofsky family. He’s developing his ear with a quartet. He’s hearing chromaticism from Buddy Petit, and Henry “Kid” Rena is showing him high notes. And then he goes on the riverboats where he’s playing Paul Whiteman arrangements and playing a slide whistle. Then he goes up to Chicago and gets in with Fletcher Henderson, listening to Guy Lombardo’s broadcast every night, and he’s doing comedy on the stage in front of Black audiences in Chicago. So, it is building and building and building, and to some critics that resulted in the crescendo of “West End Blues,” but then it’s over. But to me, this was all a prequel. He’s put the whole thing together, and now watch him take over the world. So, I hope people don’t just read this book and stop here and think that this is the end of the story, because to me, this is just the beginning.

JJM Working at the Louis Armstrong House Museum as you do, do you get the sense that people understand his importance?

RR Yes and no. I do think it’s better than it was when I started working at the museum 15 years ago. At that time it seemed as if people would come in because it was a cool thing to do if they were visiting Queens, but many were suspect of him because they may have seen him on Ed Sullivan when they were younger and never liked him because they didn’t like the way he smiled, or because their parents liked him, or because they were from the generation that thought “Hello, Dolly” was kind of jive. We heard that at the museum a lot, and it was still clinging to him until the mid-2000s, but now that rarely comes up. It’s not that everybody comes in knowing that he was a towering figure of the 20th century, but much of the previous opinion of him has disappeared. Much of that is because of the work of the Louis Armstrong House Museum – and I don’t mean just because of me personally, but because of the work of the museum as an institution.

I also feel like Armstrong is starting to take his place in the classroom. This week alone I made four presentations of Armstrong to middle school students in Brooklyn, and watching them respond to him while showing them the clip of him performing “Dinah” and sharing stories of his youth and how much he accomplished even after being arrested is gratifying. I do think that if he is put in front of kids in the classroom and discussed during times like Black History Month, he will receive his just dues as a great American. There is a lot of work to be done. I’m just so grateful that I get to be able to do this work, and to share this great man’s music, and his life.

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

.

“Armstrong never lost his humility, but he always remained very aware of his importance to the 20th century.

“Once, after passing out hundreds of dollars to down-on-their-luck friends in Chicago in the 1950s, Armstrong was chewed out by his manager Joe Glaser for giving all his money away.

“‘What do I need money for?'” Armstrong responded. “‘They’re going to write about me in the history books one day.'”

He was right.

-Ricky Riccardi

.

.

Listen to the 1926 recording of Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five play “Big Butter and Egg Man, with Armstrong (trumpet, vocals); May Alix (vocal); Johnny Dodds (clarinet); Johnny St. Cry (banjo); Lil Hardin Armstrong (piano); Kid Ory (trombone). [Sony/BMG]

.

.

___

.

.

Stomp Off, Let’s Go: The Early Years of Louis Armstrong [Oxford University Press]

by Ricky Riccardi

.

.

___

.

.

About the author

Ricky Riccardi is Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, and author of What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years and Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong. In 2022, he won a GRAMMY Award for Best Album Notes for The Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia and RCA Studio Sessions 1946-1966. He has delivered lectures on Armstrong at venues around the world and has taught Armstrong courses for Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Swing University and at Queens College, CUNY. Riccardi has a degree in Jazz History and Research from Rutgers University.

.

.

___

.

.

Acclaim for the book

.

“Louis Armstrong is quite simply the most important person in American music. He is to 20th-century music what Einstein is to physics, Freud is to medicine, and the Wright Brothers are to travel. In this indispensable and thrilling book, Ricky Riccardi guides us through the period of Pops’s own creative Big Bang, the first decades. Stunning!”

– Ken Burns, award-winning documentary filmmaker

.

“Riccardi handles the legacy of our greatest musical icon with care, laser precision, and staunch integrity. This early accounting of Louis’s community and work is an extremely important chronicle of world history. Amazing work!”

– Jon Batiste, GRAMMY Award- Oscar-, and Emmy Award-winning multi-instrumentalist, bandleader, composer, and New Orleanian

.

“Nobody knows Louis Armstrong like Ricky Riccardi. Nobody loves Louis Armstrong like Ricky Riccardi. He generously shares both the knowledge and love with his readers and has delivered the definitive guide to this seminal American musician.”

-Ted Gioia, author of The History of Jazz and The Jazz Standards

.

“Riccardi has Mr. Armstrong on speed dial. This is the only way to explain the richness of the details. Either that or he has the finest time machine on the market. Either way, everybody wins because we better understand why Satchmo is the man!”

– Sacha Jenkins, filmmaker, director of Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on February 28, 2025, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

photo by Rhonda R. Dorsett

.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read our interview with Ricky Riccardi on his book Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

*photo courtesy of the author