.

.

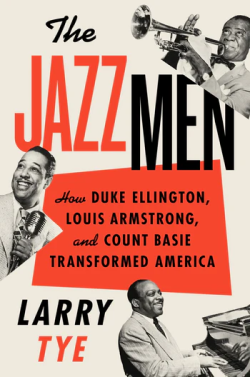

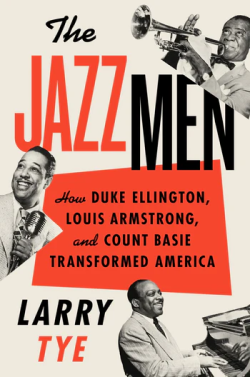

Larry Tye, author of The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America [Mariner Books]

.

.

___

.

.

…..In the introduction to his book, The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America, Larry Tye writes: “You know their names. And you probably think you know their stories. Duke was the man who seduced the country with ‘Mood Indigo’ and six thousand other tunes composed on his Steinway Grand, and who wound up on a U.S. coin and a U.S. postage stamp. ‘Satchmo’ was a multitalented rhythm maker— trumpeter, vocalist, and leading man on the silver screen— who charmed us when he crooned ‘Mack the Knife,’ and whose ‘Heebie Jeebies’ we instantly grasped despite its indecipherable English. Then there was the Count, the most inscrutable of the threesome, who proved— with his trademark flicker of the brow and tinkle on the treble— that the best place from which to conduct a band is a piano stool.”

…..And, to fans of popular music, the musical biographies of these men are indeed well-known. Their legacies as masterful, courageous, groundbreaking artists whose work impacted popular music throughout their lifetimes – and beyond – are carved in stone.

…..Tye’s interest in these men lay not so much in reminding readers about their musical achievements as in how they interacted in the complex world of discrimination and racism that they routinely encountered; how and why they hired the men who managed their careers; the many temptations they would often succumb to; and their relationships with their faith, their wives, and their money.

…..In his book, Tye tells stories that allow readers to see how the men’s constantly evolving jazz dialect, he writes, “crashed through racist ceilings in a way that formed a cultural fulcrum that no outraged protester or government- issued desegregation order could begin to achieve.”

…..Jazzmen is an intensely researched, spirited, and beautifully told story – and an important reminder that Armstrong, Ellington, and Basie all defied and overcame racial boundaries “by opening America’s eyes and souls to the magnificence of their music.”

…..Tye joined me in a conversation about his book in this August 8, 2024 telephone interview.

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

photos by William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress

|

Duke Ellington, 1946 |

Louis Armstrong, 1946 |

Count Basie, 1946 |

.

“No trio did as much as Duke, Satchmo, and the Count to set the table for the insurrection by opening white America’s ears and souls to the grace of their music and their personalities, demonstrating the virtues of Black artistry and Black humanity. They toppled color barriers on radio and TV; in jukeboxes, films, newspapers, and newsmagazines; and in the White House, concert halls, and living rooms from the Midwest and both coasts to the Heart of Dixie. But they did it carefully, knowing that to do otherwise in their Jim Crow era would have been suicidal. If James Brown, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard are rightfully credited with opening the door to the acceptance of Black music, it was Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington who inserted the key in the lock.”

-Larry Tye

.

.

___

.

.

JJM Thanks for joining me, Larry. Why did you want to tell this story?

LT My interest in this goes back to an earlier book that I wrote about 20 years ago, Rising From the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class. From the end of the Civil War until the 1960s, the Pullman porters had the best job a Black man could get in America – they got to travel the country in a way that no other Black men of that era did, they could hobnob with leading politicians and financiers and sports figures, and they made more money than was available to Black men in any other job at the time.

And when I got done writing about the Pullman porters, they made me promise that someday I would write two other books – one of which was on their favorite sports figure that they carried on the trains, the baseball legend Satchel Paige, and the other would be on their three favorite passengers of all time, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Count Basie. The reason that they were their favorite passengers says a lot about the porters and the jazz musicians, but most importantly, it says a lot about America. During that era, even if you were as celebrated a figure in American culture as Duke Ellington, Count Basie or Louis Armstrong, when you went south in an era of Jim Crow segregation laws, if you picked the wrong restaurant to try to get a meal, or if you simply picked a “whites-only” hotel in which to try to get a room, you could be anything from berated to beaten. So, when these musicians traveled below the Mason Dixon Line, they would hire a private Pullman sleeping car, which meant that if they were doing a concert somewhere like Atlanta, they knew that when they went back to the Pullman car after the concert they’d have a great meal, a plush bed, and most importantly, a safe space. And Joe, if I could go back to any moment in history, it wouldn’t be bad to go back to the private surroundings of a Pullman railroad car and have the Duke Ellington Orchestra playing just for us. That would be pretty cool.

JJM Indeed it would, Larry. What is your own experience with these artists? Did you listen to them during your childhood?

LT I had no personal experience with them in the sense of having seen them perform, and I feel terrible about that. I’ve been doing live talks all over the country and people tell me what it was like to be there in person, which makes me jealous. However, I did have the experience of listening to their music, and when I was a kid, and all the way through my dotage today, I find their music riveting. I feel like in writing this book, I’ve had the personal experience of tapping my toes in a way that is as irresistible as when you listen to the music of Ellington, Armstrong, and especially the swinging Count Basie Orchestra.

JJM Did you have a collection of their records when you were younger, or read their biographies?

LT I wish I could say that I was versed in their biographies and that I knew all about the history of jazz, but I’m a lifelong reporter and journalist, and that means I’m a dilettante – I would begin most of my days when working for a daily newspaper knowing nothing about my topic. But I would approach that day with the arrogance of a journalist, assuming that if I had a day to learn about it, by the end of the day I would know enough to write a story that would hopefully tell even people who knew something about that topic a little bit more. So I began this book with a profound ignorance about music, about jazz and about these three maestros, but thanks to 250 people being willing to talk to me, and my spending three years reading everything that was ever written about them in books, magazine stories and newspaper articles, I knew enough to hopefully teach people – even those who already knew a lot about these guys – something they didn’t know. And that is especially the case because I wasn’t trying to tell people something new about their music – everybody knows the music of Ellington, Armstrong and Basie – I wanted to write about their legacy off the bandstands, and that is, at least in my mind, as important as their musical legacies.

JJM What will informed readers learn about these iconic musicians while reading your book?

LT To start with, they will learn that while these men were born within five years of one another at the turn of the last century, and while they all lasted at the top of their game for an almost unheard of 50 years, they came from three very different worlds, which set them on three very different paths to forming their personality and musical identity.

A young Louis Armstrong (with his mother and sister)

.

Duke Ellington

.

Count Basie, 1942

In Louis Armstrong’s case, he was born in the middle of the segregated south in New Orleans, in a neighborhood that was so tough it was known as the “battlefield.” What I believe saved him – not just in a figurative sense, but a literal one as well – was him being plucked from those city streets and sent for 18 months to reform school. I say that it “saved” him partly because many of his friends who were left out on the streets didn’t make it to their teenage years, but it also saved him because in that time he learned that he could play first a bugle, then a cornet, and finally, a trumpet, better than just about anybody else on the planet. So, it was at that Colored Waif’s Home for Boys where he learned what Booker T. Washington said was the most important survival skill, which was that if you learn to do something better than anybody else could, nobody could ever take that away from you.

About 1,000 miles away, Duke Ellington was growing up in Washington, DC. in a much more middle class surrounding, and in a household that had a whole lot more resources. And when Duke was a child, he developed the persona that stayed with him for a lifetime. That was reflected in the fact that when he was a kid, every day, he would walk down the steep staircase in his family home and tell his young nephews at the bottom of the steps to bow to him. He would tell his young nieces that it was appropriate to curtsy. And he would tell everybody who was there, adults and children, to, as he put it, “applaud” because someday the world was going to know him as the great and the grand “Duke” Ellington. He used to tell lots of stories about where he got that famous nickname, but the truth is, he dubbed himself as being royalty, and he proved over the years that he was worthy of that aristocratic title.

From Washington, D.C., we move north again, this time to Red Bank, New Jersey, where Count Basie grew up. Red Bank is a suburb of New York that doesn’t have a whole lot to recommend it other than that it is the birthplace of Count Basie, and as soon as he was old enough to have a sense of what he wanted to do, he decided he wanted to get the heck out of Red Bank. He initially thought about joining the circus, but he ended up deciding that his piano playing was his ticket out of Red Bank, so he went to New York, where he learned at the feet of the great Fats Waller. After that, he returned to Red Bank only when he had to.

So, all three of these guys start out at the same time but in different worlds, which helps explain why Louis Armstrong became a “wear-your-heart-on your-sleeve” kind of guy, Duke Ellington became an elegant and aristocratic man, and Count Basie grew up as a very private guy who wanted to make his name in jazz, but who let his bandmates shine in a way that the egotistical Ellington and Armstrong weren’t able to do, which may be why Basie is considered to be the greatest jazz band leader ever.

JJM A central concern of the book and one that is likely top-of-mind with readers is how they managed to succeed amidst the rampant and overt racism of the era, and you go into this in detail, especially regarding criticism of their work by white critics, their travel challenges, the segregated venues in which they performed, and who they chose as their managers. You wrote, “The sound of their evolving jazz dialect formed a cultural fulcrum that no outraged protester or government- issued desegregation order could begin to achieve. Each of these unique and improvisational men did that in his own way.” Maybe you can provide some examples of how they fought to help disarm racism?

LT Let’s start with Louis Armstrong. He was a man who was accused throughout his life of being an “Uncle Tom,” in large part because he was a crowd pleaser who “hammed it up” while on stage. He was a wonderful crowd pleaser – he knew what made people laugh and what made them fill the auditoriums wherever he was performing. He saw no contradiction between being an artist and an entertainer, yet people didn’t accept that. Instead, they saw him mopping his brow with his handkerchiefs while performing on stage, and they saw him laughing with a big grin, and this made it difficult for people to see him as a serious guy. He used to say, as did Ellington and Basie, that he wanted his music to speak for itself.

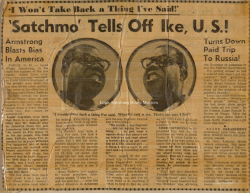

Headline to the September 17, 1957 article of Louis Armstrong calling out Arkansas governor Orville Faubus

But one day in the middle of 1957, he lost it. A young reporter asked him what he thought about what was then the most prominent civil rights flashpoint in America – the attempt to integrate the all-white Central High School in Little Rock Arkansas, which was interrupted by the racist governor of Arkansas, Orville Faubus, who stood in the doorway to the school and pronounced, in effect, that the school will be integrated over his dead body. In his response to the question, Armstrong called the governor a “m——-r”, which ended up being translated in family newspapers as “an uneducated plow boy,” and he called President Eisenhower – our war hero president – “gutless” for refusing to send in federal troops to protect these nine kids who became known as the “Little Rock Nine.” So now, instead of being attacked in the press for being an “Uncle Tom,” he was attacked for being an unpatriotic American. But the one person who listened to him was President Eisenhower, who, not long after that fusillade from Louis Armstrong – who he adored – sent in federal troops to protect those kids.

Count Basie had many indignities that he had to endure. For example, one night at a Philadelphia theater, after he had received a total of 10 standing ovations, he stood outside the venue for a cigarette when a white guy tossed him his keys and told him to go “fetch my car.” The assumption made by the white guy was that the only reason a Black man would be at that theater was to be a valet. But Basie fought back against racism. One example is that as early as 1945 he inserted a clause into his contracts that said he would only play if audiences were integrated, which was 20 years before Duke Ellington did the same thing. Basie said he wanted to speak through his music, but he spoke beyond his music, and in a way that mattered.

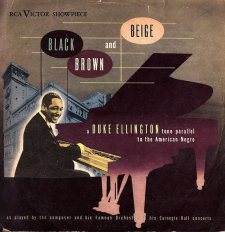

Ellington’s Black, Brown, and Beige album was released on RCA/Showcase in 1946. The suite was originally performed in Carnegie Hall in January, 1943

Ellington was possibly the most reticent on civil rights issues of the three of them, yet he wrote music that told the story of Blacks in America, most famously through his symphony Black, Brown and Beige, which very movingly told the story of the Black experience in America starting with slavery, going into the Reconstruction Era, and ending up in the civil rights era. As far as his personal activism, at one time he was in Baltimore for a performance when a group of young activists at Johns Hopkins University asked him to join a sit-in at a local diner that only served whites. He refused their first and second requests, but agreed to do so on their third request, and just as the student activists had anticipated, his participation made headlines all around the world the next day, stating that he had helped integrate the diner.

So, all three of these men had started out reticent to say anything beyond what they said through their instrumentals and through their singing, but all three of them ended up saying and doing things that helped move the dial on civil rights. White men racist enough to not allow a Black man to cross their threshold were wooing their sweethearts with the music of the Ellington, Basie or Armstrong orchestras. And white women who, if they saw a Black man walking toward them on the sidewalk would have walked to the other side of the street, would, in the privacy of their own living rooms, kick off their high heels and tap their toes to the swinging music of these great Black musicians. For once, race fell away as an issue, and America just wanted to listen.

JJM As you mentioned, Ellington wrote pieces like Black, Brown and Beige and performed concerts of sacred music. What about Armstrong and Basie? How did faith show up in their work, and how was that viewed by white America?

LT All three of them were men of deep faith. Ellington said that he had read the Bible cover-to-cover three times, and Armstrong and Basie prayed before meals. So, they all grew up with experience in the church and really believing, but that didn’t mean that they didn’t regularly violate every one of the Ten Commandments. If you pick just one Commandment – to honor your spouse – you will see that Armstrong was married four times, and even with his fourth and longest lasting and beloved wife, Lucille, he regularly cheated on her, and she knew it. Count Basie was only married twice, but he cheated often enough on his nearly lifelong wife that she left him twice and only came back when he promised to reform. The one who stayed married his entire life to the same woman was Duke Ellington, but they only lived together as husband and wife for a few years, around the time they were very young and had a son. After that they stayed married mostly because Ellington had so many mistresses – all of whom wanted to marry him – and he loved being able to tell them that he’s married and that they wouldn’t want him to go through a costly and time-consuming divorce. I was actually taken on a two-hour tour of Harlem by Duke Ellington’s granddaughter, and during it we spent time looking at the venues in which he played and everywhere that he had lived, but the longest part of the tour, by far, was being shown everywhere he had stashed a mistress.

JJM You wrote, “How, we rightfully ask now, could men so determined to heal the world cause such hurt at home?” It’s an interesting question, and it is evident this was a central challenge for each of them, especially while being on the road for so much of their lives.

LT I had written an earlier biography of Bobby Kennedy, and the Kennedys were famous for what was referred to in that era as “womanizing.” Everyone’s justification – whether it was a Kennedy or a jazz musician – was that, being on the road 300 days a year, how could anyone expect them to remain faithful? It was true they were out on the move most of the year, and it’s true there were endless temptations, but it’s also true that faithfulness is a matter of promise, of taking vows to be true to your spouse, and if they had seen their wives having affairs the way they did, they would have never accepted it. So, it’s an explanation rather than a justification.

JJM How did their “treatment” of women extend to them as fellow musicians?

LT They performed in a male dominated, macho world, and that’s the reason my book is called Jazz MEN, because there were no jazz WOMEN who lasted as long and managed to do all the different things that these men did in their performances. Women were generally relegated to roles as vocalists, and great vocalists from Bessie Smith to Billie Holiday performed at the time. These three men treated these very esteemed and talented women vocalists, on the one hand, with adoration for being a central part of their bands, but on the other hand falling victim to the same sexism that everybody seemed to succumb to in that era. They called the women “thrushes” or “canaries,” and limited them to singing roles, rarely encouraged to become instrumentalists and certainly not band leaders.

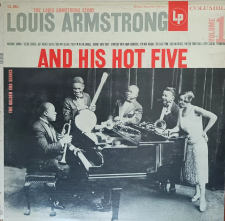

A 1951 edition of Armstrong’s 1925 – ’27 Hot Five recordings pictures his wife, the pianist Lil Hardin Armstrong (far right)

One of the few women to defy those low expectations was someone readers probably won’t recognize if I refer to her as “Lillian Hardin,” but they would recognize if I refer to her by her full name, which was “Lillian Hardin Armstrong.” She was Louis Armstrong’s second wife who appeared with him on some of the most famous jazz recordings of all time, the “Hot Fives” that Armstrong was at the center of. She was “Hot Lil” playing the piano during those sessions, and she was an arranger, a piano player, a composer and a band leader – and that was extraordinary in those days. I think she was able to do it all because she was so talented, but also because she never gave up her famous last name even though their marriage was so short-lived.

JJM She also managed his career for a short period of time…

LT Yes. And when Armstrong had been called from New Orleans to play in Chicago in the band with the great King Oliver, she told Armstrong that he shouldn’t be a sideman in the band, that he should have his name up in lights. She believed in him, encouraged him, and helped catapult him from sideman to headliner. And then he left her.

JJM While reading about Ellington, Armstrong and Basie, you’re reminded about how their key managers are themselves essential parts of jazz history, and I’m talking of course about Irving Mills, Joe Glaser and John Hammond. What are examples of how these men helped steer their careers during such a complex era?

Irving Mills

.

Joe Glaser

.

John Hammond

LT Their managers did a number of things for them. John Hammond discovered Count Basie when Basie was playing at a dive bar in Kansas City called The Reno Club, where there was a radio hookup, allowing Hammond to listen in from New York. He was so moved by what he heard that he immediately traveled to Kansas City in order to sign Basie as a client. Louis Armstrong came across Joe Glaser when Armstrong was at one of the nadirs of his career in Chicago, and Joe Glaser helped rescue him. Irving Mills discovered Duke Ellington in New York and helped catapult him to not only a prominent place musically, but he was also able to tap into Ellington’s graceful persona and successfully market his sense of elegance.

What was interesting about all three of these managers is they not only had to manage them musically, but this was during the time of prohibition when the biggest nightclubs in the jazz world were run by thugs who’d sell alcohol under the table. These tough guys who ran their clubs realized that the way to attract patrons to buy their bootlegged whisky was to book great jazz performers of the day. So, the price that these great musicians had to pay was working for really tough guys, and they needed tough guys representing them. And there was nobody tougher in Chicago than Joe Glaser, who modeled himself on Al Capone and knew how to break legs if that was what it took to protect Louis Armstrong.

One of the other interesting aspects of this is that at one time or another all three of them had managers who were Jewish, and this was part of what was the celebrated Black/Jewish alliance of the 20th century – an alliance that, sadly, has frayed today. But at that time, Blacks and Jews shared the position in American society of being outsiders who were drawn to jazz in part because they weren’t allowed to participate in symphony orchestras or in other more celebrated, more refined musical forms of the era. So, their managers were Jewish men like Glaser and Mills who were also their pals. Jews and Blacks were playing in jazz bands together as well. So, a very interesting story was playing out in the history of jazz, which was a story of various ethnicities participating in this all-American music form.

JJM There is that, but there are also well-known stories about how these managers took advantage of their clients. For example, Irving Mills would take credit for writing many songs that he had little if anything to do with from a composition standpoint, and in the case of Armstrong, he turned over his money matters to Glaser, trusting him to a fault…

LT Their feelings about their managers depended on what moment you asked Ellington or Armstrong about them – at times they credited them with having shown them a wider world and helped them achieve great success, and at other times they were upset because they cheated them or they disparaged them. It was a push-pull relationship, and what all three of these artists ended up saying is that they knew they were being taken advantage of, but they also knew they needed white men to negotiate their venue bookings and recording contracts because, as Black men, they didn’t have the leverage or clout to do so themselves. So, they alternately appreciated them and were upset with them, but in the end Louis Armstrong would say that Glaser was his “daddy,” and that “he’s me and I’m him.” All three of them realized that they had incredibly comfortable lives, and even if their managers were getting rich off of them, they were also getting rich themselves.

JJM All of this is more evidence of the complexity of the times in which these men lived and performed in. One reality of the era is the severe pay inequity – Black musicians were making a fraction of what white musicians were. Were their managers effective in narrowing that gap?

LT They were very effective in trying to close the gap. The gap was never closed, but the managers pushed as hard as they could. This was a time when America was an overtly racist country, and that was reflected in everything from the greeting that they got when arriving at various venues, to the money that they made.

There are many examples that illustrate the indignities they had to endure. For example, Louis Armstrong regularly headlined a Las Vegas nightclub that he could only enter through the kitchen. I talked earlier about how it was assumed that the only reason Count Basie would be at the theater in Philadelphia was because he was parking cars. But a story involving Ellington was something even more despicable. One time he went to Lynchburg, Virginia to perform but his manager couldn’t find a hotel that would accept Black guests. He went to one hotel and asked the owner if he’d allow the great Duke Ellington to stay at the hotel while he was performing in town, and the owner said he would on the condition that he pay extra for the sheets and the pillowcases since he’d have to burn them after a Black man slept in them. The idea that an elegant man like Duke Ellington – one of the most celebrated musicians in the world and practically in the shadow of where he grew up in Washington, D.C. – would have to endure that kind of hate and indignity is simply shocking to me.

JJM Yes, there are several disturbing stories like that throughout your book. They are tragic and awful but not surprising. An example of how they could be ripped off by record companies because they were Black involves Basie and his label, Decca Records…

The 1941 Decca release of Count Basie and His Orchestra, One O’Clock Jump

LT Yes, this was before he signed the very savvy John Hammond to be his manager. It was a contract that he entered into very naively. The deal with Decca became the epitome of exploitation, paying him a fee of just $30 – and no royalties – for chart topping tunes like “Jumpin’ at the Woodside.” So, for these records that live on today, he was getting this minuscule lump sum payment. If Benny Goodman – a white contemporary of Basie’s – had been offered that, he would have walked out of the room! The bad news is that it was a three-year contract that Basie signed with Decca, and while John Hammond was outraged by it, there was no way to change it. It was just another indignity he had to endure. The good news was that the Decca deal was early in his career, and over time Basie learned from it, and he was eventually signing lucrative recording and touring contracts. So, over time these guys were pioneers who didn’t just get upset and tolerate these conditions, they pushed back in a way that Martin Luther King, Jr. said, had it not been for these great jazz musicians, what he was trying to achieve with the civil rights movement would have taken much longer. He said they “set the table” for what he was trying to do, by infiltrating quietly their music and their notions for what Black genius could be into the white homes across America. And it made a difference.

JJM Let’s talk about that for a little bit. When we talk about these musicians we tend to focus on their beginnings and how they impacted that world, but they also performed during a time when they had so much musical competition during the civil rights era. This was a time of rock and roll, of the “British Invasion,” of Motown, and so many other historic musical movements. How did they respond to this cultural change musically?

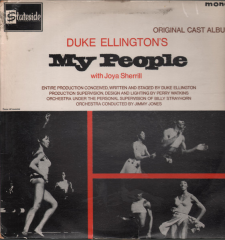

Ellington’s 1963 album My People was written and recorded for a stage show, and includes the track “King Fit the Battle of Alabam'”

LT Their music changed because they were willing to, as they would say, “speak through it.” An instance of that was during the civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, when the police chief Bull Connor turned the fire hoses on young Black demonstrators. In response to that, Ellington – whose music was generally instrumental – wrote a song called “King Fit the Battle of Alabam’” that overtly struck out against Connor and the tactics he used. The lyrics of the song (i.e. “And the Bull jumped/Nasty, ghastly, nasty/Bull turned the hoses on the church people/Church people, oh, church people/Bull turned the hoses on the church people/And the water came splashin’, dashin’, crashin’/Freedom rider go to town”) could have gotten him into deep trouble since he was going after the all-powerful white police chief while also praising the demonstrators. The use of that overt civil rights jargon by popular entertainers trying to reach out to white audiences was unheard of at the time, but he got away with it because he was so talented, and because he didn’t care if it cost him a portion of his racist white audience.

JJM Meanwhile, Armstrong was recording songs like “Hello Dolly” and “What a Wonderful World” that had a different approach to the same era…

“What a Wonderful World” was originally released as a 45 on ABC in 1967

LT Yes. Armstrong was going in an opposite direction. Early in his career he recorded heartfelt, incredibly moving pop songs that conjured up images of the Jim Crow South that he had grown up in, and later in his career he took what I perceive to be mediocre songs and turned them into classics, including the two you mentioned. But if a guy like Louis Armstrong – with all he had endured growing up in New Orleans and living in a racist world – could call the world “wonderful,” it demonstrated a great sense of optimism to the point where I remember feeling “hope” when listening to those songs. This wasn’t just during the civil rights era, it was also during the era of Vietnam war resistance, and it was inspiring to hear Louis Armstrong say that if people did a bit more loving of one another rather than hating it could change. Louis Armstrong was the one guy who could take ordinary lyrics and songs and turn them into something that made you want to cry.

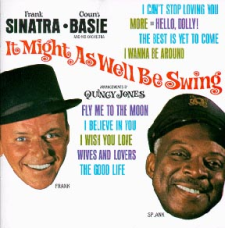

JJM And during this same time Basie made incredible recordings with Sinatra that also helped contribute to the era in a different way…

LT Yes, and the most famous – and my favorite of his recordings – was “Fly Me to the Moon.” His band was playing the music, Sinatra was crooning the tune, and it did make it to the moon because the Apollo astronauts were so taken with the song that they brought it up there with them. And when they talked with Walter Cronkite and the other television news anchors back on Earth about the music they were listening to, it helped make this song soar not just to the moon, but to the top of the record charts as well.

JJM Another topic of complexity is how they were seen in Hollywood and on the big screen…

LT That’s right. They were already performing on radio and on television, and they would also pioneer their roles on the big screen in historic ways. Louis Armstrong had dramatic roles that were generally unheard of for Black actors at the time, acting in films with major stars like Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Duke Ellington and his orchestra were in many Hollywood films, and Count Basie and his entire orchestra were playing in the middle of the desert in one of the funniest scenes in one of the funniest moves of the time, Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles. So, these men were pushing limits in every medium they could, including the big screen, and they did it successfully and in a refined way that opened the door for fellow Black artists.

JJM But the way that Hollywood caricatured Armstrong, for example, made it more difficult for him to overcome this “Uncle Tom” image that people had of him…

LT It’s true. He was part elegance on screen, and he was part what a lot of young people, black and white, thought was a caricature of Blacks. He was, again, a man of contradictions, and at times he would do what it took to do to get a role, and if that role was one of ignorance, he sometimes did it, and if another role was one of elegance and refinement, he did that as well. It gave grist to his fans and to his critics. My book is partly a mea culpa on my part for not appreciating the complexity and the bottomline genius of Louis Armstrong’s role as an artist the way I should have when I was young. As time went on, Black musicians of the bebop era that followed the early jazz era of Armstrong turned around on him – people like Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis, for example, started out embarrassed by him and ended up adoring him.

JJM What is their combined legacy, not as musicians, but as public figures?

LT The point of my book is to say that we don’t get to meaningful social change in America in a straight line. For example, if you look at the genesis of Brown v. Board of Education, it’s not like we learned in fifth grade civics class that Plessy v. Ferguson led to this next case, and it worked its way up until we finally got to Brown v. Board of Education. It’s much more of a zigzag in how we really make change that matters. And, as Martin Luther King, Jr. said, it is through the infiltration of American consciousness with the notion that if these Black jazz men could be geniuses, maybe, just maybe, they deserved equal rights as well. Armstrong, Ellington and Basie wrote the soundtrack for the civil rights movement in a way that I think is profound, and in a way that is as important as their musical legacy. And that’s saying a lot because these three men are up there on the Mount Rushmore of American musical geniuses.

.

.

“Libraries are filled with the stories of Ellington, Basie, and Armstrong, but what’s stunning is how what was said about each of them individually applies to them collectively. All captured America with their melodies and their passion. Each said he was a music maker first and last, when in reality they also were cultural and racial revolutionaries. All thrived profession ally for an unheard-of half century and defined their eras as few others did. Dizzy Gillespie, the Ambassador of Jazz, was talking about Satchmo but it could as easily have been Duke or the Count when he declared, ‘No him, no me.’”

-Larry Tye

.

.

Listen to the 1963 recording of the Duke Ellington/Billy Strayhorn composition “King Fit the Battle of Alabam'”

.

.

In this 1967 performance on ABC Television, Louis Armstrong sings “What a Wonderful World”

.

.

Listen to the 1964 recording of Frank Sinatra (with The Count Basie Orchestra) performing “Fly Me to the Moon” [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

The Jazz Men: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America, by Larry Tye [Mariner Books]

.

.

Blurbs for the book

“Tye brings his subjects to life as both forces of social change and three-dimensional human beings who lived and breathed their art, from Ellington’s soulful, ‘Shakespearian’ arrangements to Armstrong’s ‘heart as big as Earth’ and Basie’s ‘Buddha-like’ temperament. It’s a vibrant ode to a legendary trio and the ‘rip-roaring harmonies’ that made them great.”

— Publishers Weekly (starred review)

.

“Tye has an easy way of telling a story, a knack for characterization and a pacing that feels right . . . Through the marvel of their music, these jazzmen live forever.”

— Wall Street Journal

.

“Like the best music created by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie, The Jazzmen SWINGS. As Tye makes clear, their story is the story of America in the twentieth century.”

— Ricky Riccardi, Grammy Award–winning author of What a Wonderful World and Heart Full of Rhythm

.

“The Jazzmen tells an uplifting and unifying story that is especially important now, when times are so fractured.”

— Sonny Rollins, Grammy Award–winning tenor saxophonist

.

“Tye has found that there are new things to say about The Three Musketeers of Jazz. Read, learn, and enjoy.”

— Dan Morgenstern, jazz author, historian, editor, educator, and former director of the Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies

.

.

About Larry Tye

Larry Tye is the New York Times bestselling author of Bobby Kennedy and Satchel, as well as Demagogue, Superman, The Father of Spin, Home Lands, and Rising from the Rails, and coauthor, with Kitty Dukakis, of Shock. Previously an award-winning reporter at the Boston Globe and a Nieman fellow at Harvard University, he now runs the Boston-based Health Coverage Fellowship. He lives on Cape Cod.

.

.

___

.

.

This telephone interview took place on August 8, 2024, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.