.

.

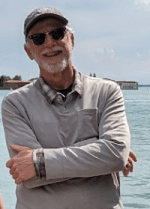

photo by James W. Blackman

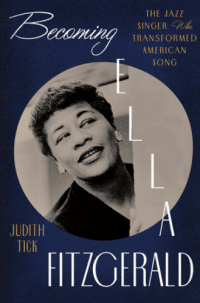

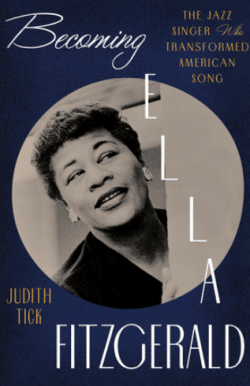

Judith Tick, author of Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Music. [Norton]

.

.

___

.

.

…..Ella Fitzgerald has long been acknowledged as one of the greatest figures in jazz. Known as “The First Lady of Song,” Ella’s vocal range and her ability to improvise via her signature scat singing led to enormous worldwide popularity.

…..But those of us of the Boomer generation who may have seen Ella Fitzgerald on television toward the end of her career as a modest, grandmotherly woman with a polite disposition, and who would entertain us with scat performances of hit songs like “A-Tisket A-Tasket” and “Mack the Knife,” had little understanding of how she had to confront the enormous obstacles facing mid-century America – race, gender and class – that could have otherwise thwarted her ambition.

…..In Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song, the book’s author Judith Tick writes that Ella “fearlessly explored many different styles of American song through the lens of African American jazz, [and] treated jazz as a process, not confined to this idiom or that genre,” and who “changed the trajectory of American vocal jazz in this century.”

…..An example of her genius is how, Tick writes, Ella “transformed the culture of an entire repertoire, deftly infusing with swing the sophisticated show tunes from the golden age of Broadway musical from the 1920’s and ‘30’s.” In the process, her work singing these songs “ignited a double transformation: by reinventing herself as a singer, she transformed a vintage repertoire; and by modernizing it, she laid the foundational stones for what would soon be known as the Great American Songbook. One transformation begat another.”

…..Utilizing documents from the Black and trade press that were unavailable to previous biographers, Ms. Tick’s book is a rich, emotionally stirring, exceptional work that explores every element of Ella’s legacy in great depth, reminding readers that she was not only a great singing artist, but also a musical visionary and social activist.

…..Ms. Tick. who is professor emerita of music history at Northeastern University, talks with me about Ella – and her book – in this wide-ranging October 23, 2023 interview.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

.

IISG, CC BY-SA 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Ella Fitzgerald in the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam; February 18, 1961

.

“I think I’ll keep singing jazz tunes for a while and then I’ll look for something new. A lot of singers think all they have to do is exercise their tonsils to get ahead. They refuse to look for new ideas and new outlets, so they fall by the wayside. But there’ll always be new ideas in jazz – just as long as there are enthusiastic kids trying to crash this business. I’m going to try to find out the new ideas before the others do.”

-Ella Fitzgerald, October, 1947

.

Listen to the 1965 recording of Ella Fitzgerald singing Billy Strayhorn’s composition “A Flower is a Lovesome Thing” [Universal Music Group]

.

___

.

JJM Ella Fitzgerald is a giant of a topic. How did you come to the place of deciding to write her biography?

JT I’m not a jazz scholar; I’m a historical musicologist who specializes in American music and cultural approaches to music and women’s history. I came right out of second-wave feminism and the big rise in interest in American music and American studies during the Bicentennial decade of the 1970s. So, I learned what American jazz really is – as a musical language, culture, and civilization – as I wrote this book.

JJM Where does Ella fit into that for you?

JT Ella is the labor of heart and mind. I grew up with her, because my mother, who was born in 1917, the same year as Ella, loved swing, pop singers, and dancing. And because of both of my parents’ love of music, I had access to the LP’s that came out of the 1950s, and I immediately gravitated to the Song Books – Cole Porter, George Gershwin, and others too. So, I just loved Ella from those recordings.

At the same time, as a young kid I also listened to rock and roll in its early stages while also studying classical piano in the most conventional way with a very fine teacher. So, I learned to play Mozart while discovering that, through Ella, there was also this wonderful world of classic jazz standards, which I then sang while I was in college.

I have this very genuine, natural approach to the Ella that most people know, the singer of what we now call “classic pop” but at the time were known as “standards,” which jazz musicians had to learn to play. At the time I didn’t really know about the jazz connection that deeply, but you can’t listen to the Song Books without absorbing swing, which embodies her originality as a jazz pop singer.

JJM Did the Song Books help shape the way you visualized this book?

JT Initially they did, but after doing research I came across a of volume of information of her life “before the Song Books,” which was a period with only a skimpy history that didn’t give us much sense of the complexity of the world she grew up in, or even, to some extent, in Chick Webb’s band. Her “after the Song Books” history was pretty skimpy as well because she went her own way so much during her time of recording for a rather esoteric record label, Pablo, and there wasn’t much written about that part of her life either. So, the “before the Song Books” and “after the Song Books” was my starting point, until I realized there was a continuity to her whole life, that she was a transformational artist to herself. We saw these periods, but she didn’t necessarily think of them as being separate as I had experienced them initially.

JJM She appealed to a variety of listeners…

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Ella Fitzgerald singing, Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman in the audience; c. late 1940s

JT Yes, she could appeal to very sophisticated listeners – particularly other jazz musicians – while at the same time she was satisfying the general listener. She always had a complex view of her audience, and to her, there was no one ideal listener. In the classical world, some composers like Mozart embraced the blend of an intellectual approach and a connoisseur approach, while also reaching the general listener. Ella learned to do that, and wanted to do so because as she evolved and as she understood the power of her audience connections, it became her mission to reach as large an audience as possible.

People from all over the world loved her. I used to be amazed at how much the jazz critics obsessed about text, when Ella had such a large audience outside of the United States who didn’t speak English. So, here are all of these sophisticated lyrics reaching people who could not have possibly understood Cole Porter’s double entendres, yet it went over anyway because Cole Porter was a great songwriter whose melodies and harmonies were wonderful, and Ella understood that and communicated the spirit of the music that embodied the words in its own way.

JJM And it seemed as though she had a simplistic view of what her role was as a singer, which was to make her audience happy.

JT Yes, as Leonard Bernstein would say, to “emphasize the experience of music.” This view evolved for her over time. She started out as a swing singer with Chick Webb, who himself was a great artist, and they shared their love for making instruments and voices dance. Then, after he died, it was early war time so people wanted music that touched different kinds of emotions – feelings of loss or insecurity that also provided comfort. Ella understood that people wanted more than “my jittery ballads.” She was called a jive singer or a swing singer for so long, and then she slowly developed her own ballad repertoire. And in wartime she was a consummate entertainer who could balance the music necessary for comfort with the music we need to survive.

photographer unknown

Chick Webb

JJM There is a lot of complexity in her story. Well before the time of recording the Song Books was the 1930s era of playing with the drummer and bandleader Chick Webb…

JT She grew up in the very segregated world of Jim Crow, and toured during the 1930’s and 40’s in the South where she played before segregated audiences and dealt with racism at every turn. This was a world where Black people weren’t allowed to use the bathroom or buy a cup of coffee, and where the music venues had ropes down the middle to segregate the audience.

Ella didn’t want to be trapped by the stereotypes of the vocalist. She wanted to use her voice to express the freedom she heard in saxophone playing or in trumpet playing, and to have the same access to freedom of expression that male instrumentalists were allowed. She wanted to sing as soulfully as Coleman Hawkins played “Body and Soul” on saxophone, while also singing with the complexity of Dizzy Gillespie playing trumpet. Her seeking Dizzy out as much as she did was a revelation, because her managers in the commercial world didn’t want her to be involved with bebop.

Norman Granz in 1947

JJM Later in her career, one of her managers was the impresario and Verve Records founder Norman Granz, a white man who was known for presenting jazz to integrated audiences as a form of racial justice, which he famously did while promoting his Jazz at the Philharmonic tours. He began booking Ella in the late 1940s, well after her time leading Chick Webb’s orchestra ended. At the time, she owed the IRS a great deal of money. Did this financial dilemma impact Granz’s vision for marketing her?

JT By the time Norman met Ella, he had emerged as a great impresario who put together the Jazz At The Philharmonic (JATP) traveling ensemble of great instrumentalists who played in many styles – primarily swing, bop, and samba. This ensemble included Ella’s husband, the bassist Ray Brown.

Breaking down racial barriers in public places was a primary motivation for Granz to even start JATP. When Ella joined him she was being managed by Moe Gale and was under contract to Granz’s rival label, Decca, where Milt Gabler reigned supreme, and who was her artist and repertoire manager. When Granz recorded JATP he couldn’t include Ella because of contract prohibitions, but nevertheless he understood her brilliance and how popular she was. He felt her potential was not being developed and knew she had so much more to offer. After he wrestled her away from Gabler and Gale, he gave her a sense of the opportunities JATP offered her musically, which gave her good reason to trust him as her manager.

He paid off Ella’s debt, which was entirely consistent with the way he treated his musicians in general. He’d made a fortune and didn’t skimp on musician salaries, paying for first class hotels, hospitality suites, and for the best performance venues. She saw this while traveling with them, and it became a natural step for her to want to leave her manager. But getting her away from Decca was a very hard thing for Granz to do. Granz was a marketing visionary, and given the racial complexity of the era, he was also a courageous impresario.

JJM Yes, from a musical standpoint alone he was an unbelievable impresario, putting people like Charlie Parker, Lester Young, and Oscar Peterson on stage together and, from a cultural standpoint, opening wider the door for jazz to be performed in major concert venues. He was consistent throughout his career for using jazz for social justice, and Ella fit in to his vision for how to present jazz, and in the process, you wrote that, “over time her singing with the JATP changed not only her career, but the course of American vocal jazz.”

JT Yes, because she stood up there with the same stature, leadership, and power as an instrumentalist. She had her own set, but then they all jammed together. Ella progressed from ballrooms and Black theaters and social clubs with Chick Webb, to white clubs in the 1940s, then into jazz clubs, and then with Granz she performs in concert venues and large arenas, where she is being marketed brilliantly before mass audiences.

In addition to managing her, Granz was very generous in giving her the financial security he knew she needed. She was very lucky because he was a smart investor for her, and his paying her IRS debt was the beginning of a long relationship where he looked after her financial security.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1956 recording of Ella Fitzgerald singing Cole Porter’s “You’re the Top” [Universal Music Group]

.

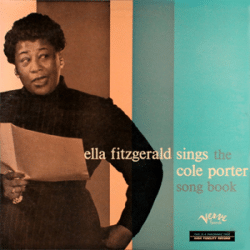

JJM The genesis of the Song Books is of great historic interest. Do you feel that Granz and Ella understood the potential for success they would have from creating albums devoted to music composed specifically by the likes of Cole Porter, Gershwin and Rodgers and Hart?

JT Yes and no. At one point she told Norman not to do it because she was concerned about the possibility it may bankrupt him. So, she didn’t know. But he had had some success with making anthologies of standards with Oscar Peterson, for example, who recorded Song Books on the piano, and Ella had done a Gershwin Song Book with Decca, but I think both of them were surprised by the success of the Cole Porter album. She sublimated her personality to convey what she called “the thing itself,” and wanted to perform the music in the way she thought it was written. She didn’t want to turn every song into a statement.

JJM What does that mean?

JT It means that she didn’t want to use a song to project her own personality. For example, she didn’t scat very much in the early Song Books, and she didn’t transform the melody deliberately to imprint her own personality on the material. She took a backseat to the material, which allowed us to hear 32 songs in a row [the number of songs on the Porter Song Book] of Porter’s music. Can you imagine 32 treatments from a singer who was going to use every single one as a major statement? It would be exhausting! So, she used swing as her way of approaching the material, and that gave it a contemporary vitality.

JJM How did Norman Granz approach the production of the recordings?

JT He believed that the first take was the best take and had this notion of documentary purity, that what you do first is the most authentic, giving a listener the equivalent of a field recording. The song didn’t need to be recorded over and over again. He felt that the great jazz musicians he worked with would give him their best efforts with the composition right away. But it wasn’t quite so simple. There was so much material and he didn’t want to do more takes than necessary, nor was he concerned about new engineering and recording techniques. What he and Ella wanted most was this notion of jazz spontaneity.

JJM How did Cole Porter feel about Ella’s recordings of his songs?

Cole Porter in the 1930’s

JT It depends on who you read. Norman Granz said Porter liked them, but his biographer reported multiple reactions, as do other Song Book composers. At times, the more that jazz changes the original composition the more likely that songwriters will object to them. It’s a little like a classical composer saying after hearing their composition; “It was nice, but I didn’t compose it.” There can be a conflict between a songwriter who believes that the way he wrote it is the way it should be sung and an interpretation of it. But she bridged that gap because of the respect she brought to the material. The songwriters felt respected.

JJM Richard Rodgers, Ira Gershwin, and so many other Song Book composer all seemed to love her work on their songs…

JT She projected respect, and respect wins people over. What followed was their admiration for her achievement.

JJM Your book reminded me of the immense marketing vision Verve had for the Cole Porter Song Book. Thirty-two songs on a double LP presented in a gatefold format that looked like a coffee table book, and for $9.95 in 1956, which is over $100 in today’s dollars. It was a highbrow way to promote vocal jazz, and extremely successful…

The cover of the 1956 album Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Cole Porter Songbook [Verve]

JT It was extremely intellectual, as if it were a Modern Library project. Ella Fitzgerald Sings The Cole Porter Song Book is a cultural artifact of the 1950s, and not just because of the recordings – the cover and the documentation inside were important too.

When you look at the photographs of farm laborers and working-class people from the 1930s, the respect for them is right there, as is the compassion. But without that respect, the compassion looks sentimental. The same is true for the Song Books. What you see is tremendous respect in the way they market them, and the care taken with every detail. Given this respect, listeners welcomed the material with an open heart and an open mind.

JJM In today’s world, where music listening is most prevalently experienced via streaming services, music typically doesn’t receive this kind of treatment. And while Ella’s music is still easily accessible and still sounds great, without the physical packaging listeners don’t have a way of understanding how dynamic the albums were, and what they meant to the culture at the time.

JT Yes, and that is where historians come in – to restore context so listeners can go back and understand the magnitude of the moment, and of the product. But we can’t expect contemporary audiences to want to do that because they’re too busy listening to the present, so a historian has to make them want to understand what they’re hearing. Critics do it initially, and then historians do it later, which may provide today’s audiences with an understanding of how it felt to people who first experienced it. New performances of the material do that as well. For example, when an artist like Cecile McLorin Salvant sings an old standard, she knows its history, and it comes through in her performance of it.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1959 recording of Ella Fitzgerald singing the George and Ira Gershwin composition, “But Not For Me” [Universal Music Group]

.

JJM What was Ella’s impact on the Great American Songbook?

JT She expanded the songs’ meaning from when they first emerged in the 1930s and 40s to classics that defined an era not only of the past, but the way the present looked in the 50s. She modernized and revitalized them and gave them new meaning for audiences who grew up with this material, and for new audiences who could experience an era of excellence in American popular music history.

JJM Did Ella have input into the arrangements or ensembles that backed her on these recordings?

JT It depends on the arranger. For example, when Buddy Bregman – the first arranger of the Song Books on Verve, and who was in awe of Ella – brought in strings, she was very happy with that. And at the time, Norman Granz told him that Ella can have whatever she wants; if she wants more strings, she can have more strings.

This was during a time when arrangers were very important. As jazz and pop evolved, the swing band enlarged with classical instruments, so they became a hybrid of both a swing band and a symphonic orchestra. This allowed for a greater musical range for arrangers like Nelson Riddle, who was famous for incorporating instruments like the tuba and the harp into his sound. In an arrangement of his “But Not For Me,” for example, there is a lot of classical arranging for the harp that is right out of French Impressionism.

JJM And Granz was providing Ella with input by telling these arrangers to give Ella whatever she wanted…

JT That happened sometimes, yes. The arrangers wanted to please her, to have her immersed in what they were creating. They also wanted her respect by writing an arrangement that would show off her voice in her best register, and to stay out of the way of her voice so she could express herself while also giving musicians solos that would provide comment on her singing. This is the art of arranging that the Song Books relied on. No matter who the arranger she worked with during her career was, she never controlled him, but they understood who she was.

JJM You can’t have a conversation about Ella without talking about the giants she recorded with and those she shared the era with. Concerning Billie Holiday, you wrote that “the question of Ella’s status as a jazz singer grew more urgent in the early 1960s, after the death of Billie Holiday in 1959 gave rise to assessments of that loss.” How did Billie Holiday’s death affect Ella’s status in the jazz world?

photos by Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress

Billie Holiday, 1949

.

Ella Fitzgerald, 1940

JT Billie Holiday was somewhat older than Ella and was a model for her in terms of her ability to assert her primacy as a vocalist. When Ella and Billie began they sang a single chorus, which means that during a three-and-a-half-minute recording they sang for less than a minute. In Ella’s case, the big star was Chick Webb’s band, whereas Billie asserted her independence in a small group chamber music setting and never really became known as a big band, swing song singer. She was a club singer – her favorite milieu was intimacy and working with a small group. Ella was much more of a swinger.

Before Billie Holiday died, there was a coterie of jazz critics who constantly compared them, and it was understood that she was a singer with a singular originality that the jazz world had not ever seen. Ella, on the other hand, did not attain Billie’s mythic stature during Billie’s lifetime, it came later as her career evolved. So, in the 1960s after Billie’s death, a coterie of jazz critics preferred a certain kind of emotional expression – one that Ella Fitzgerald didn’t possess.

JJM You wrote that the esteemed critic Nat Hentoff felt Ella had “’little girl charm’ while Billie was more complex and human when she sang,” and that “this assessment pained Ella.”

JT Yes, this pained her because he didn’t see the beauty of her voice, and he trivialized virtues she possessed as a singer that Billie Holiday did not.

JJM Early in her career, some critics used the term “peach fuzz voice” as a way to describe the style of Ella’s singing…

JT Yes, that was when she was a young girl. It was a way to describe her innocence – it was exaggerated, but it stuck around. Her lack of sexuality was also exaggerated.

And some of her critics tended to do cross-examinations of her work rather than be neutral. They had a strong ideology about what a jazz singer should be, and if she didn’t fit that then she’s diminished. To this day I have conversations with critics who feel that Ray Charles was a far greater singer than Ella, or that Celine Dion is Ella’s equivalent. Another one still believes her sound was “emotionally immature.” What can you say to that? If you want to find fault, you can find it in anybody.

JJM And Ella was a person who had real challenges with her self-esteem, not only because some people were critical of her work, but also because of the cultural criticism – for example, that she wasn’t the “glamour girl” other singers were….

JT Yes, that she wasn’t beautiful.

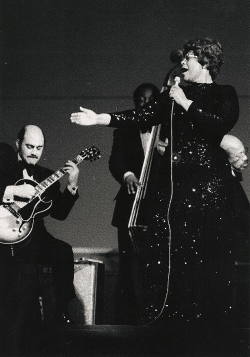

JJM You write about the quality of her 1970s work with the guitarist Joe Pass…

Hans Bernhard/CC BY-SA 3.0 Deed/via Wikipedia

Ella Fitzgerald with guitarist Joe Pass; 1974

JT Yes, that collaboration needs more scholarship, and historians should take another look at that because their entire period together is quite amazing; she’s creative and inventive in different ways. This was during her “after the Song Books” phase, when she didn’t have popular hits like “Mack the Knife,” but nonetheless continued to grow and expand and produce wonderful albums of inventive and creative growth.

JJM And these were on Pablo Records, another Norman Granz label that also recorded the likes of Roy Eldridge, Count Basie, Oscar Peterson and Milt Jackson. For whatever reason I overlooked much of what was recorded on Pablo – probably because of the dreadful album covers – but your reverence for these recordings inspired me to discover Ella’s compelling work on them.

JT Ella didn’t like those covers either, and they were recorded at a time when Norman didn’t care if they made money. So, he was willing to put out products that wouldn’t necessary make a profit.

JJM Well, it showed…

JT Yes. So, some of the marketing skills that had elevated the Song Books to their status were greatly lacking on Pablo. They are the products of an aging entrepreneur, and he didn’t care anymore. They are documents of an era more than they are commercial recordings.

JJM Ella made several interesting records during this “after the Song Book” era that didn’t sell well…

JT That’s right. She wasn’t a singles artist while recording for Decca, and she didn’t sell LP’s later in her career. Other than Sinatra few vocalists did, and the reason he did is because he had a toolbox to keep his musical career going – he was an actor and television personality whose huge persona transcended his LP’s.

JJM So, in order for Ella to make money, she had to tour extensively…

JT That was always true. It takes a different set of tools to be a successful TV personality. Dinah Shore could do it, but even Sinatra didn’t have a weekly television show. It takes a unique personality to run a TV series. So, after the 60s, what Ella did that was quite unique was to incorporate contemporary music into her performances and recordings as a way to reach young people and bridge the 1960s “generation gap.” For example, she was an early proponent of working with Beatles tunes, and she even had a hit with “A Hard Day’s Night” in the United Kingdom. She didn’t have one snobbery bone in her body, so she had no trouble crossing generational lines. She sang rock tunes as well as pop songs by Burt Bacharach, and she gave these songs the respect she felt they deserved.

JJM The Beatles felt she was successful in interpreting their music…

JT Yes, they did.

JJM And she even sang “Sunshine of My Love” by the rock band Cream, which was led by a young Eric Clapton…

JT Yes, and it worked at times. And she also recorded soul music, which she was very influenced by because it allowed her to liberate her voice. She took what she needed from all of this music and returned it with respect. The only genre that she really felt challenged by was country and western music. That was really hard for her.

JJM You write about her reverence for the music of Burt Bacharach, a composer who many critics didn’t take kindly to. Did she ever want to record a Song Book of his tunes?

JT She never talked about doing a Song Book, but she certainly praised his songs, many of which she sang. The big thing for her in the 1960s is when Norman Granz reunited her with Duke Ellington. She sang more Duke Ellington songs than anyone else did in that era, and in doing so restored interest in his music for the next generation.

JJM Would you say she was the best vocal interpreter of Ellington’s music?

JT Absolutely, and that isn’t even part of the jazz narrative. The emphasis on discussions like “who is the better singer between Billie and Ella” overshadows other far more important historical trends, such as the importance of Ella Fitzgerald’s role in sustaining Duke Ellington’s music through their Song Book recordings. A problem with the misuse of the word “greatness” is that it stymies our understanding of the past, and we keep asking the same questions about Billie versus Ella, rather than new questions which acknowledge Fitzgerald’s unique contributions.

photo by Brian McMillan

Ella Fitzgerald in 1986

JJM Ella toured extensively all over the world for many years, which of course impacted her ability to be present for her son Ray. Did she have late-in-life regrets about her absence as a mother?

JT Working mothers always have regrets because they’re always trying to juggle, and Ella expressed those regrets toward the end of her life. My book relies on new sources like digitized newspapers – especially the Black press that embraced Ella so powerfully in the 1940s – and archives that are new so that I could dig up accurate information about her ancestry. With the help of Ray Brown, Jr. and family members like her cousin Dorothy Johnson, I was able to set the record straight about her extended family. Dorothy told me that earlier stories written about Ella late in her life made it seem as if she was all alone, but she had family, and they were there for her. And, because she was a grandmother and grand aunt, there were kids around in Ella’s life and she played an important role in theirs.

JJM And many of these family members were instrumental in helping Ella raise Ray…

JT Yes, she had an aunt who took care of Ray. He of course missed his mother, and because of her work she missed so much of the routine growing pains of a child, but he understood that she loved him and her work was necessary to support him. Yes, there were periods of estrangement, and yes, she had regrets. No one is immune from regrets. She missed having a true love in her later life, and she had a complicated friendship with her boyfriend, Dr. Booker, who was a philanderer.

JJM Yes, an imperfect guy but it seemed as if Ella was loved by him at a time she needed it.

JT Leontyne Price once said “I’m married to my gift,” which could apply to Ella as well.

JJM What can a modern-day female vocalist learn from Ella Fitzgerald?

JT That she needs to be open to taking risks, and to be open to whatever kind of music she needs to perform in order to support her gift. To protect it. And to respect it.

.

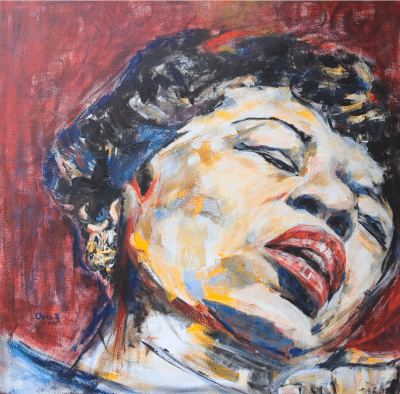

“In Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” by Christel Roelandt

“I was sitting in a store the other day and a lady saw me and said, ‘Oooh – my dreams have come true! It’s my singing lady!’ And I looked my worst – I had my sneakers on, and an old skirt. But she stopped and said, ‘We love you,’ and then another girl came, and soon everybody was asking me for autographs. I said to myself, ‘Well, you can’t beat this kind of love.’ I’ve got about three bags of mail here that I haven’t even answered yet – people who wrote me in the hospital. You start thinking, was it all worth it? And I say, yes.”

-Ella Fitzgerald, in a 1987 conversation with journalist Leonard Feather

.

.

Watch a 1957 film of Ella Fitzgerald performing “Angel Eyes”

.

.

___

.

.

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Music. [Norton], by Judith Tick

.

.

Judith Tick is professor emerita of music history at Northeastern University. She has published award-winning books and articles about American music and women’s history in music, including Ruth Crawford Seeger: A Composer’s Search for Music. She lives in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Click here to read and listen to “A Baker’s Dozen Playlist of Ella Fitzgerald Specialties from Five Decade,” as selected by Judith Tick

Click here for more details about the book

Click here to read an excerpt from the book

.

.

___

.

.

Praise for the book

“Ella Fitzgerald made becoming a great artist seem effortless. She hid her will, her drive, and her originality behind the mask of a modest, soft-spoken woman. Now, at last, Judith Tick shows exactly how Fitzgerald explored and shaped every form of American popular music. In the process she thwarted all the boundaries of class, race, and gender that threatened to confine her. Tick’s musical knowledge is impeccable; so are her reporting and her scholarship. ‘I won’t be left behind,’ Fitzgerald used to vow. This stirringly complete biography ensures that she never will be.”

― Margo Jefferson, author of Constructing a Nervous System

.

“In this radiant, rich, no-stone-unturned biography, Judith Tick shows us how Ella Fitzgerald ‘became’ not only one of America’s greatest vocalists but a brilliant innovator who forever changed the status of ‘the female singer’ in her time and beyond.”

― Paula J. Giddings, author of Ida: A Sword Among Lions

.

“Becoming Ella Fitzgerald is a treasure―a comprehensive, deeply researched, and documented biography that finally gives Ella the complexity and depth that she deserves. Placing Fitzgerald in the intersection of race and gender at mid-twentieth century and overturning often repeated half-truths about her life and career, Tick highlights the beauty and artistry of Fitzgerald’s voice and the full range of her genre-crossing career. Becoming Ella Fitzgerald is essential reading for anyone interested in the Ella, jazz, or American popular culture.”

― Ingrid Monson, author of

.

“[Tick] exposes speculation, fills fissures with fact, and finds a fresh feminist heroine of transformative authority.”

― John McDonough, senior contributor, Down Beat

.

“More than a decade in the making, Becoming Ella Fitzgerald is a biography truly worthy of the ‘First Lady of Song’.”

― Ricky Riccardi, Grammy-winning author of What a Wonderful World

.

“Remarkable.… [O]pens up whole areas of her story that have seldom been explored in print, and in the process reveals a woman whose exceptional artistry infused a bewildering variety of material with a touch of genius.”

― Alyn Shipton, host of BBC jazz programs and research fellow at the Royal Academy of Music

.

“At last, we know where Ella came from and how she became our beloved First Lady of Song. Becoming Ella Fitzgerald is a first-rate job of research and a great read.”

― Dan Morgenstern, director emeritus, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University

.

“Judith Tick’s much-needed updated biography uses new research and keen musicology, and brings forth a revealing and fully convincing portrait of Lady Ella as visionary, social activist, and still-modern singer.”

― John Szwed, author of Billie Holiday: The Musician and the Myth

.

“A magisterial biography…rendered in luxuriant prose…. This is a superior addition to the shelf on America’s jazz legends.”

― Publishers Weekly (starred review)

.

“[A] comprehensive and fascinating biography of an American music titan….Essential for casual fans of jazz and music history and Fitzgerald aficionados alike, this thoroughly impressive work will be hard to equal. As masterful and wonderful as its subject.”

― Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on October 23, 2023, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read our 2023 interview with Stephanie Stein Crease, author of Rhythm Man: Chick Webb and the Beat That Changed America

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.