.

.

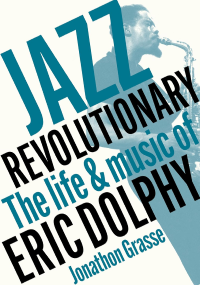

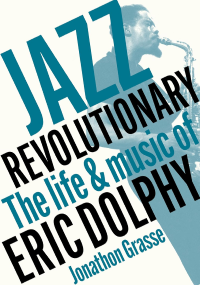

Jonathon Grasse, professor of music at California State University, Dominguez Hills, and author of Jazz Revolutionary: The Life and Music of Eric Dolphy [Jawbone]

.

.

___

.

.

…..Eric Dolphy was one of jazz music’s first true multi-instrumentalists, and a pioneer of avant-garde technique. His life cut short in 1964 at the age of 36, his brilliant career touched fellow musical artists, critics, and fans of jazz music through his innovative work as a composer and bandleader.

…..An only child of Afro-Latin immigrants, Dolphy grew up in a segregated Los Angeles and embraced a life studying music, initially dreaming of becoming a classical musician. As a budding clarinetist, Dolphy earned a scholarship to a summer program for young musicians at the University of Southern California, only to have it rescinded after school officials discovered he was Black. He became consumed by the R & B and bebop culture emanating from the clubs of Central Avenue, and youthful plans now included hopes of a career in modern jazz augmented by the abundant work in the city’s film, radio, and television studios. After serving stateside during the Korean War years, he returned to Los Angeles and met and played with the ascending jazz musicians of the community – Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman and Buddy Collette among them – eventually joining the drummer Chico Hamilton’s quintet in 1958 before moving to New York the following year.

…..In his brief career, Dolphy collaborated with many of the era’s most significant modernists. Among his early mentors was the bandleader, arranger and composer Gerald Wilson, who wrote and arranged progressive charts for Duke Ellington, Benny Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Dolphy was the other reed player in Coleman’s 1960 double-quartet album Free Jazz, the continuous free improvisation album that defined a new (and controversial) movement in jazz. He shared the stage with John Coltrane at a time when Coltrane was experimenting with his own music and moving deeper into the avant-garde. He was a critical contributor to the work of Gunther Schuller, whose compositions combined classical and jazz technique into a sound he coined as “Third Stream.” He was an essential player on Oliver Nelson’s Blues and the Abstract Truth, one of the most highly regarded jazz records of the early 1960’s. And he played often in Mingus’ musically demanding mid-sized ensembles known as the Jazz Workshop, which required intense and adventurous musical exploration from his players. Mingus, a close friend of Dolphy’s, said that Dolphy “knew a level of the language which very few musicians get down to.”

…..And this language included the sounds of animals and birds. He told the critic Leonard Feather that he would “remember when the birds used to whistle along with me, back home in California and I’d drop whatever I was doing and play along with them…I’ve always liked birds and I like to sound like them.” There were no boundaries to what he imagined for his music, once telling the writer Nat Hentoff that “no sound was alien to jazz.”

…..Not everyone understood Dolphy. As a member of the era’s “avant-garde” he had his admirers, but the old guard critics who didn’t examine Dolphy’s music in the context of his genius emerging during the era’s racial complexity heard noise, hate, and anarchy in his playing. Some characterized his music as “anti-jazz,” or “musical nonsense” – jarring criticism that impacted his career to the point where he couldn’t always get regular work. His recording contracts were unsteady, and while he led among the early 1960’s most ambitious and electrifying recordings and contributed as a sideman to a number of influential jazz albums, his musical reputation caused club owners to (mostly) shy away from hiring him, eventually leading him to attempt a new life in Europe, where he died of undiagnosed diabetes in Berlin.

…..In his book Jazz Revolutionary: The Life & Music of Eric Dolphy – the first full biography of him – Jonathon Grasse examines Dolphy’s timeless musical achievements as well as the harsh, personal, and often curious reactions to them. While the book is centered on the artist, Grasse’s consistently impressive accounting of Dolphy’s music is also an important component of the book. The albums on which Dolphy appears are interpreted title by title, track by track, bringing readers into each recording via a skillful and descriptive writing style.

…..Dolphy once famously said “When you hear music, after it’s over, it’s gone in the air. You can never capture it again.” Perhaps. But a critical achievement of Grasse’s book is that it effectively inspires readers to experience a deep and personal exploration of this unique artist’s historic recorded works, reminding us of the complexity of his biography along the way. In my December 3, 2024 interview, Grasse discusses his compelling subject.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

“Jazz has always been defined by the eloquence and power of collective expression and individual improvisation. In Dolphy’s uncompromising solos on alto saxophone, flute, and bass clarinet, and in his dynamic original compositions, audiences heard a revolutionary voice that helped launch a new era of expressive freedom in jazz. He forged a unique style within an emerging climate of post-bop, experimentalism, and free jazz, at a time when African Americans were engaged in intense political struggles for freedom and equality. These vitally important Black Americans were his contemporaries: Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. Dolphy died less than two years before Stokely Carmichael’s introduction of the ‘Black Power’ slogan, yet it is clear to many that his music channels a similar vein of dissent and liberation challenging America’s deep stain of inequality.”

-Jonathon Grasse

.

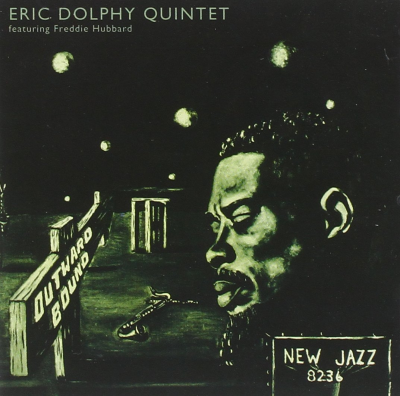

Listen to the 1960 recording of Eric Dolphy playing his composition “G.W.” (from the album Outward Bound), with Freddie Hubbard (trumpet); Jaki Byard (piano); George Tucker (bass); and Roy Haynes (drums). [Universal Music Group]

.

JJM It’s a pleasure to have you joining me, Jonathon. Congratulations on this excellent book.

JG Thanks very much, Joe.

JJM You write quite impressively as a musicologist, and also as an ethnomusicologist. Who are some of the jazz writers you admire?

JG Ted Gioia is at the top of the list. For this project I both enjoyed and cited Lewis Porter’s and Bill Cole’s works on John Coltrane, and Brian Priestly’s Charles Mingus biography. Eric Porter’s historical depth is invaluable as is the case with George Lewis, and Robin Kelley’s incredible Thelonious Monk book which set a new standard. I never did read much in the way of regular jazz journalism, but Dan Heckman and Ben Ratliff nearly always seemed to say so much so well.

JJM What brought you to writing a book on Eric Dolphy?

JG I have been a fan of his for my entire adult life. I was never a serious jazz student in my youth because I broadened out into other areas of music, but I always followed a handful of the avant-garde, free jazz players of the 1960’s era. I was a big Coltrane fan, and I caught Ornette Coleman shows in the San Francisco Bay area whenever I could in the 80’s and early 90’s, but interestingly enough it was Frank Zappa’s Weasels Ripped My Flesh album that includes a fantastic, bizarre avant-garde composition, “Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue,” that made me hungry for new music and curious about Eric Dolphy. I heard that in high school in the mid-70’s and then came across a couple of his Prestige reissues in my local library, which absolutely blew me away.

His music locked into my soul from the very moment I heard “G.W.,” the opening track from his album Outward Bound. And, as I proceeded through life, pursuing an academic career that eventually led me to move to Los Angeles in the mid 90’s to attend UCLA, I began a side project that I ended up calling the “Dolphy Diary” because other than a few sources – such as the Simosko-Tepperman book [Eric Dolphy: A Musical Biography and Discography] and Alan Saul’s wonderful Dolphy website which I site throughout the book – there was no great resource for him, or a timeline of facts and figures and album names. As I built this diary, his life became somewhat confusing for me, and I started to recognize some issues in his biography that didn’t add up. And, while he was born in LA, there didn’t seem to be much of a groundswell of interest within the local jazz community to research his life, so my pet hobby was to catalog his albums and build a chronology of his life, which led to my “Dolphy Diary.” I had written a definitive book on the music of the region of Minas Gerais and anticipated writing another book on Brazilian music during my sabbatical in Brazil, but COVID wiped out much of my network there. Given those circumstances, and since all this information I had been gathering on Dolphy was intriguing me, I decided to write a book on him instead.

JJM What were his dreams as a young musician growing up in Los Angeles?

JG Eric Dolphy had a very profound respect for all music. He became a musician in the deep sense of the word as a child – he took on the clarinet, the flute, alto sax and oboe all by junior high, and was very good at them as an adolescent. Various sources speak to his interest in classical music and in playing in a symphony orchestra, which of course makes sense since his musical experiences in public schools would have revolved around band music and classical music because jazz wasn’t necessarily taught in the schools in the 40’s and 50’s. So, when he progressed into young adulthood, jazz wasn’t a focus in his college studies.

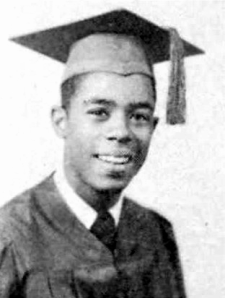

Eric Dolphy’s 1947 high school photo

I think another thing that encouraged him as a young musician was the rapid and huge growth of the entertainment industry in Hollywood film studios, on radio, and in the clubs of Central Avenue, which was a big neighborhood for jazz during the 30’s and 40’s. It was basically considered the African American part of LA, and real estate red-lining and segregation and the Central Avenue scene sparked a whole other planetary system for Dolphy’s coming of age, because he knew people like the pianist Hampton Hawes as well as a whole slew of other young soon-to-be-famous jazz virtuosi. So, he probably had a utopian dream of sorts that led him to believe that because he’d become a fine musician, he could now become a studio musician or maybe even play in the symphony. But, lo and behold, there exists these tragic undertones of racist policies; for example, he was denied entry into a summer session at USC for a Youth Music Camp because of his race.

So, Dolphy had a real open mind about music even as a young person, and this is seen later in his life by playing with the likes of Gunther Schuller and Charles Mingus, and how he was enthralled with romantic-era symphonies and avant-garde music.

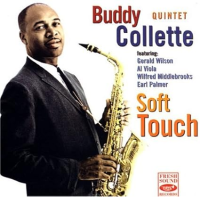

JJM His teacher was Lloyd Reese, who also taught fellow LA musicians Mingus, Dexter Gordon, Buddy Collette and Hampton Hawes. What did he learn from Lloyd Reese, and who were some of his other early teachers?

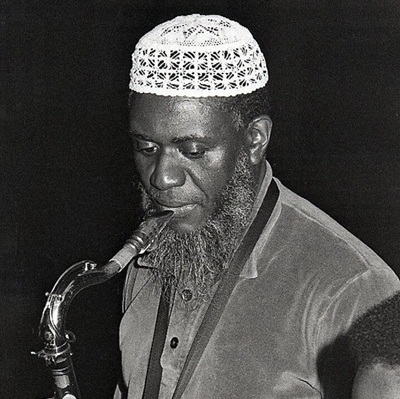

Buddy Collette, 1962 (Fresh Sound)

JG Lloyd Reese was a master teacher, and he and his wife converted their home right off of Central Avenue into a little music academy, and became very well known for that. So, he taught these great musicians, but they also hung out in his home and jammed together in it, running through things they learned from Reese. The multi-instrumentalist Buddy Collette was several years older than Eric Dolphy and had already been out of LA and in the army, and he helped pave the way for some of Eric’s early successes, particularly in recommending him for Chico Hamilton’s quintet. He didn’t really study with anyone other than Reese, although he took lessons from Collette, and he took flute lessons from an Italian concert flutist named Alberto Socarras who lived nearby. He also had contact with other teachers who were active in the African American community who had the need for Eric to fill out an ensemble here and there.

He must have taken lessons of some kind from Gerald Wilson, who at the time was at the top of his game as a trumpeter, bandleader and composer who toured extensively but wound up coming back to LA, which is when he and Eric became close friends. I wouldn’t consider Wilson an instrumental instructor of Eric’s, but he was no doubt a mentor, especially as an arranger and composer.

He also benefited from three public school music teachers: Ola Ebinger, Helen Bicknell, and Elise Baxter Moening. I do want to emphasize the role of public schools. He must have really enjoyed himself and had positive experiences within them because he stuck with band music through elementary, junior high school, high school and all the way into LA City College, which he entered as a band player. By that time, when he was only 18 or 19 years old, he was really on top of a wide range of instruments. Though it isn’t clear, he may have studied informally a bit with two band leaders he played under, Percy McDonald and Alma Hightower.

JJM Who was the first to hire him?

JG He was hired as a bandleader while in his first semester in college – a young Christian women’s group hired him for an occasion, probably a dance that may have had him playing R & B or easy listening music. Charles Mingus hired Eric for a dance, but it was Roy Porter who hired him for his first breakthrough gig. While Dolphy was in college he walked into an audition call for Porter’s 17 Beboppers big band, and just landed the gig, ultimately becoming the alto sax player in the band.

photo via Discogs

Roy Porter

Porter was a phenomenal drummer who played with Charlie Parker and the bebop heavyweights. So, when bebop hit in LA in the mid-40’s, he played with all kinds of folks, joining some combos and traveled around with them, but he got tired of that and formed his own band, which didn’t last long, nor did the record deal he got at the time. The label cut him after his first record. But in terms of Dolphy’s first job, working with Porter is the standout event as a young man going to college and living in LA. This went on for about 18 months, and there were some ups-and-downs, but they played a lot, and being the lead alto in Porter’s 17 Beboppers was a great resume stuffer.

Also, during my research I found two African America newspaper sources – the Sentinel and the California Eagle – that had ads and references in articles allowing me to piece together how Dolphy was beginning to be recognized, and it wasn’t just from working with Porter. He was also playing with Nat Meeks’ Be-Bop Orchestra, so people saw him play and witnessed his skills in concerts. Interestingly, Meeks eventually married one of Dolphy’s childhood friends Elvira (Vi) Redd, who became an amazing musician herself. Eric also gigged briefly with Monte Easter’s Challengers while with Porter. So, the news got out that Dolphy could really play, he could sight-read anything, had a great tone, and was a total professional. He also had these quirky, individual, Parker-esque bebop chops that he built on year-after-year, starting as a young person.

JJM He served in the Army during the Korean War. How did that impact his career?

JG He was out of LA for a little less than four years, but he was a band member during his time in the US Army for almost three of those years. It is what he did professionally in the ranks, and he must have played his horns for several thousands of hours of rehearsal practice, ensemble, and performances. Then, before he got out of the Army, he went east and ultimately received a certificate from the Naval Music Academy. When he returned to LA, I’m sure these experiences during the war helped him land some pretty cool gigs.

JJM How did his meeting Ornette Coleman in Los Angeles affect his vision for his own music?

JG Meeting Ornette was one of the major crossroads of Eric Dolphy’s artistic life – as was meeting John Coltrane, of course, and a couple of other people who came through LA during that time. Ornette opened his eyes to all kinds of possibilities and validated his own ear. He’s hearing all these things that he’s trying to fit into his solos and his compositions, and along comes a slightly younger guy who is rough around the edges, not nearly as deeply trained as him but who is nonetheless writing cool heads for his tunes. And people like Don Cherry and Bobby Bradford were hanging around in that milieu Coleman was the center of. While Dolphy was very fortunate to have fallen in with them, it wasn’t as deep as some people suggest. He wasn’t interested in playing like Ornette, but this “free jazz” notion of Ornette’s was a game changer for Dolphy. He saw Ornette as an accomplished enough musician to continue his professional path and to get gigs as a “working musician,” while at the same time taking part in these wildly experimental get togethers. Ornette changed the jazz world with what he was playing, so Dolphy was all-in on that. He knew what was happening, but he wanted a safe gig, and Chico Hamilton was that safe gig.

.

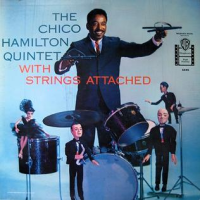

A musical interlude…Listen to Eric Dolphy play alto sax on Duke Ellington’s composition “In a Sentimental Mood,” from the 1958 Chico Hamilton recording The Original Ellington Suite [Universal Music Group]

.

JJM What intrigued Chico Hamilton about Eric Dolphy?

JG Eric’s friend Buddy Collette had been in Chico Hamilton’s band. Buddy and Chico went way back together as fellow musicians, all the way to the time they were kids. Hamilton needed a multi-instrumentalist wind player, and Collette saw that Dolphy was hitting his head against the wall in LA. At the time, Eric had a gig at the Oasis night club on Western Avenue, and Gerald Wilson was helping him get all sorts of studio work, playing R & B and rock and roll. Anyone could see that Eric was a virtuoso, and he had already picked up the bass clarinet, and was really good on alto and flute. That’s a pretty odd grouping of instruments to routinely go to at a gig with or in a recording studio and play the way he did. That multi-instrumentalism and his sight reading and musicianship sold itself to Chico Hamilton, who often seemed to play the fence, musically – at times playing something easy listening, and others touching on the avant-garde. He spread himself a little thin that way, but Dolphy was grateful for the break that he got, and Hamilton got quite a player in Eric Dolphy. That ends up being the big link to Dolphy’s move to a solo career in New York.

JJM Dolphy felt torn about playing what you describe as Hamilton’s “easy listening” music while the likes of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane were, for him, taking jazz in a more interesting direction. Did that accelerate his desire to move to New York?

The Chico Hamilton Quintet’s With Strings Attached (1958), which included Eric Dolphy on alto saxophone, bass clarinet, and flute

JG In a general way, yes, the Chico Hamilton Quintet was his ticket out of LA to New York. During his time with Hamilton, he had some ups and downs aesthetically – he was able to play, but not all the material was to his liking, that’s for sure. But it paid well. And as you suggest, at the same time, these two people he knew were just kicking ass, right? Ornette gets his recording contract with Contemporary and releases all these amazing records and ends up in New York, and that is where Dolphy, coincidentally, ends his tenure with Hamilton and signs his own recording contract with Prestige. It is important to remember that part of Dolphy’s career, that he was being recognized for his work at that time.

JJM You wrote that joining Mingus may have been the best thing that could have happened to Dolphy at that particular time. What did Dolphy learn from Mingus?

JG A lot, including what to do and what not to do, because Mingus was pretty hard on his players. Mingus was already well on his way, with or without Dolphy. Eric put an incredible spin and shine on the Mingus Workshop sound for sure – there are so many great Dolphy solos, and he carried an enormous presence. Dolphy’s big opportunity was to be able to play free with Mingus – he plays pretty “out there” on Mingus recordings, at times even more so than on his own albums. I listened to everything Dolphy played with Mingus, many, many times, and I got the feeling that Mingus really had a circus going – it wasn’t Ornette Coleman, and it wasn’t free jazz, but it had an element of wicked individuality that Mingus encouraged Dolphy to experience. You could even hear Mingus on some recordings saying to Dolphy, “Go man. Go!,” encouraging him to develop his own sound – a vocabulary that already included bird calls and human sounds and noisy effects, in addition to the post-Parker, post-bop virtuosity of him playing rip roaring solos over all these brilliant chord changes. So, Dolphy was throwing all this new stuff in, which Mingus encouraged. How many other opportunities would he get at such a high profile to do that? Maybe only a handful of other people would be in that position.

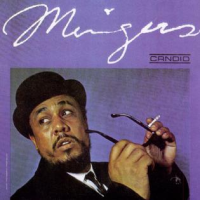

Mingus is Charles Mingus’ 1960 recording on Candid Records that featured Eric Dolphy

The other thing is that because Mingus had a residency at the Showplace, he had an opportunity for constant gigging. It wasn’t just jamming in a loft – these were gigs during which people could see him lighting it up. That’s a pretty remarkable thing to step right into; he was only in New York for a couple of months, in early 1960, before he began playing regularly with Mingus. He wasn’t paid well, but that wasn’t unusual since Mingus didn’t pay anyone well.

JJM Their personal relationship was so important to Dolphy, and he counted on Mingus for work when he wasn’t able to lead his own groups, or record his own albums. The people who impacted Dolphy and who he in turn touched reads like a “who’s who” of jazz in the post-bop era. But it’s not just the people – consider the movements he was a part of. As we already know, Gerald Wilson is in this story, as is Ornette, Coltrane, George Russell, Oliver Nelson, and Gunther Schuller, who was so involved with composing and recording third-stream music – which was, simply stated, a movement merging of jazz and classical music. What was it that Schuller saw in Dolphy?

JG What Schuller saw was a great musician. Dolphy was a technical person on three instruments, which, if necessary, is a great resource for an orchestra. And Dolphy was not only a great musician, but he plays jazz. And, he didn’t just read the music, he liked classical music as well as contemporary classical music. He was challenged by it, and to have someone like that in an ensemble who, when Schuller pointed his baton at him, will give you an Eric Dolphy solo is priceless. There were dozens of jazz musicians who could have been in that position who wouldn’t have lit his pieces on fire the way Dolphy did. And I say that because the critics said so. And while I reserve the right to talk about how harsh jazz critics were on Dolphy, some of the mainstream newspaper reviews of Schuller concerts describe Dolphy’s playing as amazing, often criticizing Schuller’s composition while, in the same review, applauding Dolphy’s performance within it.

“Eric was one of those rare musicians who loved and wanted to understand all music. His musical appetite was voracious yet discriminating. It extended from jazz to the classical avant-garde and included, as well, an appreciation of his older jazz colleagues and predecessors. He was as interested in the complex surfaces of Xenakis, the quaint chaos of Ives, or the serial intricacies of Babbitt as in the soulful expressiveness of a Coleman Hawkins, the forceful ‘messages’ of Charles Mingus, of the experiments of the ‘new thing.’”

– Gunther Schuller

.

The cover of Gunther Schuller’s 2011 autobiography

Schuller was a fascinating guy – this whole third-stream thing is a different planet from the jazz that’s played in clubs, but doing what he wanted to do was one of the freedoms that Dolphy enjoyed, and crossing jazz with classical was something he was very much interested in. So, with Dolphy, Schuller got essential things he looked for in a musician – a great sight-reader, and a multi-instrumentalist with a post-Bop solo style. Plus, he likes playing with Schuller – it is not just a gig to Dolphy. They became friends, they would talk music, they would rehearse often, even in Dolphy’s apartment.

The other thing is just the fact that time-and-time again I’d hear about what a great person Dolphy was – a good friend who was easy to get along with – and he was likely that way with Schuller as well. To Schuller, Dolphy was a great colleague, he wasn’t just an employee, or just another person in the ensemble. This kind of interpersonal generosity can’t be ignored, because in the music world you get tired of hot-headed prima donnas you’d frequently have to meet and work with. Schuller, on the other hand, had this incredible person to work with.

JJM Another person of major consequence to Dolphy and his career is John Coltrane. Why did Coltrane want to have Eric Dolphy perform with him and his quartet?

JG I think that also has something to do with the quality of human being that Dolphy was, going back to the mid-50’s in LA, when they first met. I don’t know exactly how they met, but I think their friendship spawned a musical friendship – while they were both jazz musicians, they were much more than that, and I think they were looking for something beyond jazz. They both grew musically beyond jazz in baby steps, and in painful extensions of it they were rebuked for by the jazz critics, who really slammed them.

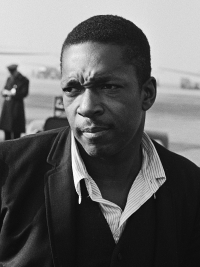

Gelderen, Hugo van / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

John Coltrane in 1963

Coltrane never put his horn down; people don’t realize that he played for hours and hours every day, and he saw that musical commitment in Dolphy as well. They were both consummate musicians. And while there are of course other musicians like that, they had been friends. After meeting first in LA, they met up on the road when Dolphy was in the Chico Hamilton Quintet – they played in festivals and must have run into each other. So, they had camaraderie, a friendly relationship.

Coltrane had such a big hit with “My Favorite Things” and with the album Giant Steps that he was able to call his own shots, which is not something he would take for granted. That’s a plateau, so his career was really revved up by that time. He was a big name, and because he could call the shots, Dolphy was going to be in his group. McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones were there and I think they were a little coy about Dolphy’s presence, and, like some of the jazz critics who ripped Coltrane for associating with Dolphy, I think there may have been a little bit of tension there, but I don’t put much focus about that on the book. There’s nothing really to go on. Having Dolphy play in the band was really Coltrane’s call.

A side topic to bring up is that during the shows Coltrane would solo first. Could you imagine having to step up in a club and follow Coltrane night after night? That’s magic! Coltrane loved Dolphy’s sound. He heard what Dolphy was trying to do, playing more outside, trying to invent new ways of fitting timbral coloristic ideas into solos and wide ranges and skips and leaps. Coltrane respected that a great deal – Dolphy having to follow him and playing flute, bass clarinet and alto, all the while holding his own and forging a new path. Even after Dolphy left and Coltrane hired Jimmy Garrison on bass – which becomes his classic quartet – Dolphy still sat in a bunch of times. He still played with Coltrane up until the spring of 1964 – before he left with Mingus for Europe – it just wasn’t a regular thing.

JJM A major theme of your book is the disdain many of the old guard jazz critics had for Dolphy’s playing, but before getting to that I want to ask you who some of his early critical supporters were?

JG Yes, it was important for me to have some balance because there was so much negativity among critics concerning Dolphy’s work. Nat Hentoff and Martin Williams of Jazz Review, and Don DeMichael of Downbeat were three early supporters, but there were also some mainstream newspaper critics and African American newspapers that plugged his recordings and covered him whenever they had a chance.

JJM Meanwhile, critics like Downbeat’s John Tynan, Ira Gitler and Leonard Feather, as well as the trumpeter Rex Stewart, and of course several prominent musicians – including Miles Davis – took seemingly every opportunity to pillar him. Was there a particular event or recording that triggered this disparagement?

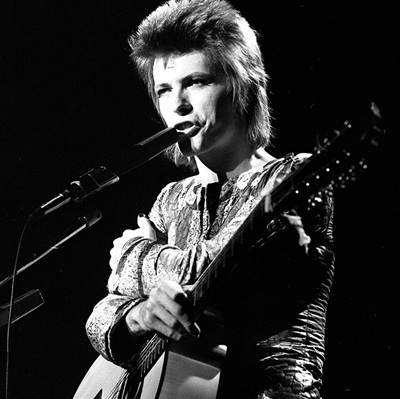

“I heard a good rhythm section go to waste behind the nihilistic exercises of the two horns. Coltrane and Dolphy seem intent on deliberately destroying [swing]. They seem bent on pursuing a anarchistic course in their music that can be termed anti-jazz” …[and] …”musical nonsense currently being peddled in the name of jazz.”

–Downbeat writer John Tynan, in a November, 1961 review of a Renaissance Club (Hollywood, CA) performance

JG That would be Tynan’s “anti-jazz” invective in response to the Coltrane quintet’s Renaissance Club gig in Hollywood. Downbeat’s Gitler, Harvey Pekar, and others disparaged him badly in several record reviews.

The general issue critics had with Dolphy was his sound and his tone. His pitch and vocabulary had a lot of repeating gestures, and he worked different registers on his instruments, which rubbed people the wrong way. I tried to be fair with the critics who were so negative because they were just doing their jobs, telling readers what they like and dislike about Dolphy’s music. But, there is little doubt that they had a negative impact on his career. It would have been a little different if Dolphy had gone on to get gigs and do well in life over a long career, where you could see this criticism as something that just happened during his early years. But since he only lived a short life that wasn’t the case, and ultimately this criticism caused him to be driven away. You can’t lay the blame for this on one person and you can’t even really blame the critics, but that whole blanket response was very real. I ran across interesting sources concerning this, one of whom was the late pianist Geri Allen, who wrote about Dolphy’s critical reception. So, there’s already a layer of critical interest in how Dolphy and the Black avant-garde was treated at that time. Ornette Coleman himself was so sick of being vilified in the press that he took a sabbatical from playing gigs.

JJM Some of the critics referred to Dolphy as an “angry” sort of a player, which is of course a racist trope…

JG John Tynan’s reference to Dolphy’s playing as being “anti-jazz” really got into the language that people used when describing him. Other Downbeat writers, for example, would refer to him as the “anti-jazz Dolphy,” which in hindsight was despicable – but you could also make the case that at the time they were just saying that they don’t like him. But it all added up to a kind of ambush, which is now an historic moment in jazz criticism.

JJM In 1961, Dolphy appeared on 23 albums, but in 1962 that work slowed to a trickle. It’s safe to assume this is connected to some of the criticism. After the “anti-jazz” criticism, he couldn’t get work at clubs, nor did he even have a recording contract. What kind of work did he take on in order to keep stay afloat financially?

JG He had to hustle for jobs. He wasn’t getting gigs or residencies for live performances with his own group, so he had to work with Mingus. When we think of him working with Mingus and Coltrane, we think of all the artistic accomplishments, but that is also his livelihood, and when that was taken away, he didn’t have much. Add to that his Prestige contract ended, and there were no side gigs, so his best option at the time was to leave New York for sideman work with some jazz groups in Washington D.C. for a couple of summers running. His work was very hit-and-miss, and 1962 was really one of the “miss” years. When he was recognized and given an award for his playing, a famous response of his was to ask if this meant he would now get work? The answer was “no.”

His groups weren’t really hired for clubs. I can’t say that I ever found steady references pointing to him getting a lot of gigs where he led his own group. The Gaslight Inn gig in October of 1962 was the first recording in over a year, and as we know, you don’t get paid a lot for a one-off gig. He needed residencies, and he needed a little tour to make a living. When we were talking about Gunther Schuller earlier, those were just gigs. He paid the rent with that money, right? So, he dealt with a lot of hardship, and I believe the negative criticism and bad press ruined his career. Coltrane even said that he hated to see the impact all the “anti-jazz” talk had on Eric’s career. So yes, the mainstream jazz press was collectively painting a nasty picture of him. The Downbeat “Blindfold Tests” that Leonard Feather conducted, where he played a Dolphy tune to incite a negative reaction from a seasoned musician, was very bizarre. Why print that stuff? Did he think it was funny to have Miles Davis calling out his fellow musicians?

So, as I say, it is fair to say that, in hindsight, the bad press ruined Eric Dolphy’s career. But you know what? At the same time, Dolphy took a lot of artistic risks on stage and on his records. He played what he wanted to play, and he paid the price. He was a true artist, and he knew what he was doing. He went down that road and he didn’t compromise.

JJM He did, of course, record several major albums as a leader. You describe one of them, Out to Lunch, as his “masterwork.” What is the significance of this 1964 album?

JG It has Eric Dolphy’s sound all over it. Of course, all of the great musicians on the album played their own solos, but Dolphy wanted certain parts to be freer. And he got that. There’s an atmosphere and personality that is cast over those sessions which can be heard in the mood, and in the quirkiness of the freer parts that really hold it together. The drummer Tony Williams and bassist Richard Davis are just fantastic throughout that entire album. Bobby Hutcherson on vibes and Freddie Hubbard on trumpet stepped up to the challenge and play incredibly well. The result is an album that is the perfect combination of composition, jazz soloing and a kind of free ensemble that’s quirky and avant-garde and fresh, even today. It includes a great variety of Dolphy soloing on his three instruments, and he composes the charts. The flutist James Newton mentions in his writing that he did some alternative arrangements, writing out modal material as a little key for musicians to read on certain parts. So, I do feel Out to Lunch is a masterpiece, and I know so many other people think so as well.

Would he have gone down that road even further and made another album like this several years later? I think so. He was very happy with that record. Sadly enough, we don’t have any more about Dolphy’s own thoughts on that, and that’s why I am hopeful that down the road more personal papers can be found that can somehow shed more light on the man and his views.

JJM His death was an absolute tragedy. Here’s a guy who lived a clean life – he stayed away from the drugs that devastated many of his peers, including Coltrane – but he died at the age of 36 due to undiagnosed diabetes. Seems hard to imagine that he didn’t know he suffered from such a routinely diagnosed disease…

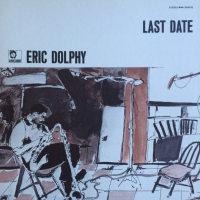

Dolphy’s album Last Date was captured live in Hilversum, Holland on June 2, 1964, and was his final recorded performance. He died on June 29 of that year.

JG That’s right. I don’t think he knew, but there exists the chance that he did. It’s possible he may have known that he was diabetic and just didn’t act on any kind of medical advice, but there is no proof that he knew. It is remarkable that he wouldn’t have known, because he had to have experienced some excruciating symptoms that could have included everything from a decrease in mental acuity to hunger pains, as well as other recognizable symptoms that show up with advanced diabetes. He had a couple of mouth sores that never healed and which kept him out of some gigs with the Mingus Workshop, and his fiancé, the dancer Joyce Mordecai, said that he was having hallucinations and wasn’t behaving right. There is also a reported instance where a man apparently saw him on the street, sitting on a bench, recognizing that he was a musician at a club where he’d seen him perform. When he approached, Eric told him that he needed something sweet to eat, meaning it is possible he was having some sort of hyperglycemic episode.

The cause of his death was likely insulin shock. He went into a coma, which meant that even if the doctors who were trying to save his life were able to do so there would have been a strong chance that he would have had brain damage. The story is that they tried reviving him with an insulin shot, but it was too much insulin. I really doubt the other anecdotes about his death, and I go out of my way to say that he wasn’t murdered. And there is no reason to believe the story you hear about how doctors assumed he was a drug addict. A doctor had come to the hotel the day before and prescribed some kind of tranquilizer after being assured that he wasn’t a drug abuser. That’s basically the story. His passing is sad and unfortunate regardless of the details, which I doubt anyone will ever fully know.

JJM You discuss a wealth of unreleased recordings that have come out in the many years following his death. Do you have any knowledge of any others in existence?

JG I don’t know what the labels have and what has been destroyed, but it is important to remember that Blue Note spent hours and hours recording Out to Lunch. The group was in the studio all day, recording multiple tracks, so I don’t know if they erased or lost them, but if not, Blue Note could release the complete Out to Lunch session, which would mean multiple takes of all those great tracks. I doubt that they kept everything – only the label would know. There must be others. Unfortunately, Prestige sessions were basically one take recordings, so there isn’t likely anything to mine there. There must be Mingus and Coltrane broadcasts that could be digitally restored in some way, but the quality may not be any good. There are studio recordings from his last weeks in Paris that have never been released.

JJM You have done so much extensive research on Dolphy and his recordings, probably as much as anyone has ever done. Having completed this research, and after having access to all this great material and history, if there was one live performance of his that you could have witnessed, what would it be?

JG Interesting thing to think about. I guess it would have been his last New Year’s Eve concert with Coltrane, which would have been in New York in 1963. He did two New Year’s Eve shows in New York in a row, and apparently great lineups were assembled. Coltrane’s quintet was supposed to be recorded for release – I assume by Impulse! – but I don’t know that for sure. Amiri Baraka (as LeRoi Jones) wrote a review on the concert, saying it was a great show. I also would have enjoyed seeing Dolphy with Herbie Hancock at the Gaslight Inn in 1962. That would have been a thrill.

JJM What do you hope readers will take away from the experience of reading your book?

JG I hope that they listen to the music. Everything’s online now, so there’s nothing stopping anyone from using the book as a launch pad to revisit Eric Dolphy’s playing. All of it is just remarkable. You mentioned the name Oliver Nelson earlier in the interview, which is an example of what an incredible sideman Dolphy was. Everyone knows his albums as leader. It will now be easier for readers to hunt and peck for Dolphy’s sideman solos. There are just so many magical moments throughout his entire discography, and having people discover them as a result of reading my book would be the ultimate pleasure for me.

.

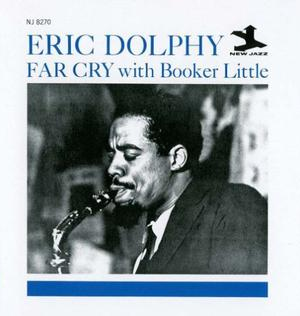

The cover to the 1962 album Far Cry (with Booker Little) [Prestige]

“There’s so much to learn, and so much to try and get out. I keep hearing something else beyond what I’ve done. There’s always something else to strive for. The more I grow in music, the more possibilities of new things I hear. It’s like I’ll never stop finding sounds I hadn’t thought existed.”

-Eric Dolphy

.

.

Listen to “Hat and Beard” from Eric Dolphy’s 1964 album Out to Lunch, with Dolphy (bass clarinet); Freddie Hubbard (trumpet); Bobby Hutcherson (vibes); Richard Davis (bass); and Tony Williams (drums). Dolphy’s composition refers to the pianist Thelonious Monk [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

.

Jazz Revolutionary: The Life and Music of Eric Dolphy, by Jonathon Grasse [Jawbone]

.

Click here to read the book’s introduction

.

.

About Jonathon Grasse

Jonathon Grasse is a professor of music at California State University, Dominguez Hills, where he teaches world music, music theory, and composition. His work Hearing Brazil: Music And Histories In Minas Gerais is the definitive English-language study on that region’s musical traditions, a book complimented by The Corner Club, in which he examines Milton Nascimento’s and Lô Borges’s 1972 album Clube da Esquina. His articles have appeared in Popular Music and the Yale Journal Of Music And Religion, among other publications. Born in Calistoga, California, in 1961, Jonathon lives with his wife Nanci in West Los Angeles.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on December 3, 2024, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read our interview with Richard Koloda on his book Holy Ghost: The Life and Death of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler

Click here to read our interview with Brent Hayes Edwards, co-author (with Henry Threadgill) of Threadgill’s memoir, Easily Slip Into Another World: A Life in Music

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.