.

.

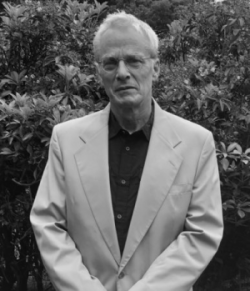

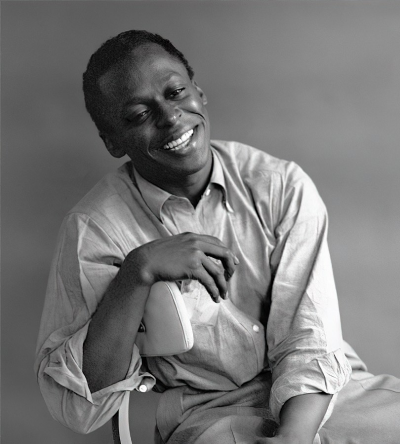

Photo: © Avery Kaplan

James Kaplan, author of 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the Lost Empire of Cool

.

.

___

.

.

.

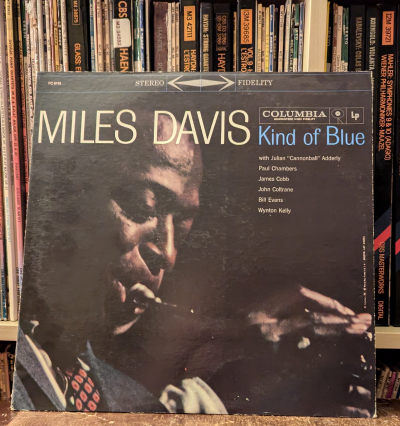

…..Miles Davis’s 1959 Columbia Records album Kind of Blue has been an integral part of the world of music since 1959. This particular copy has been in my record collection for 56 years.

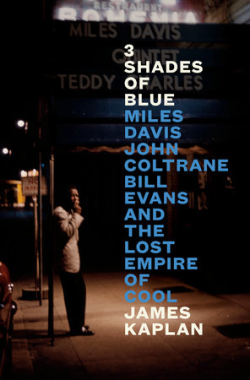

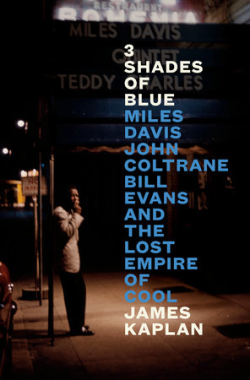

…..Anyone who loves jazz music has their own story about how they discovered this album, and may even remember where they bought it and how it impacted their lives after. Mine gets told within this interview I conducted on July 31, 2024 with the esteemed writer James Kaplan, whose 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the Lost Empire of Cool [Penguin Random House] is indispensable for readers with interests in the three geniuses at the core of the book, jazz history, music history, and of the cultural history of mid-20th Century America.

…..No introduction is required of the recording. What is important to know is that while the book is centered on Kind of Blue and the brilliance of the music and its musicians, it is not just a story about the session- as the author points out, that has been accomplished quite ably before.

…..It goes beyond that. Think of it as a story about the jazz world before, during, and after its recording – how these musicians came together, played together, and grew together (and often apart) as a result of it. It is about the complexity of their collaboration and the musical and personal challenges they faced during a time when jazz was in need of reinvention – when the existential challenge of cultural relevancy and financial survival was heavy on the bandstands and in the recording studios.

…..It is also a story of what came after Kind of Blue, when the musicians blazed new remarkable (and not always successful) trails of their own, creating within a musical world now enamored by the fresh sounds of the British Invasion, Motown, and rock and roll radio, and during a time of massive social and political change.

…..If you feel the depth of impact of these events, and for this era, and want to have a master storyteller like Kaplan present it through the lives of three genius musical artists, you will have an immense enthusiasm for this book.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

“Kind of Blue was a thing all its own, and that is what has really made it endure for the last 65 years. The word “timeless” is way overused these days, but that album is truly timeless because it is literally outside of its time. It was recorded in March and April of 1959 but doesn’t sound like 1959, and it doesn’t sound like 1954 or 1969 either. It doesn’t sound like any time, it is just its own thing, and people had trouble figuring that out at first, but then over the years more and more people began to realize how wonderful listening to this album made them feel.”

-James Kaplan

.

Listen to the Miles Davis/Bill Evans composition “Blue In Green,” from Kind of Blue, with Miles Davis (trumpet); John Coltrane (saxophone); Bill Evans (piano); Paul Chambers (drums); and Jimmy Cobb (drums).

.

JJM It is great for you to join me, James. Thank you. What inspired you to write this story?

JK After writing the two volume Frank Sinatra biography, people seemed to feel that I was somehow able to pull off this trick of writing about music, which, as the late Martin Mull memorably said, is like “dancing about architecture.” It is hard, but I really enjoy doing it and I go about it with a certain amount of passion. After writing a short biography of Irving Berlin a few years ago, of which I am very proud, I was looking for my next project, and began discussing this with my editor at Penguin, Scott Moyers, who had an idea about writing a book about Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, but as I told him, there already was a perfectly good book about that recording which was written wonderfully by Ashley Kahn.

But talk of Miles made me remember back to when I was a young cub reporter in the 1980s and wanted to be hired by Vanity Fair magazine, whose great days were just beginning and, one heard, paid writers very well. One afternoon, I received a call from my brother Peter W. Kaplan – who eventually became editor of the New York Observer for ten years – who told me that he had been in touch with an editor at Vanity Fair, and that they were about to publish an excerpt from Miles Davis’s forthcoming memoir and needed a profile of Miles to accompany the excerpt, which required somebody who knew jazz to go interview him. Peter told his Vanity Fair editor that his brother knew everything there was to know about jazz — which, to put it mildly, was an exaggeration, but I got the assignment.

I was properly terrified on two counts – first, because I knew nothing about jazz, and second, because it was Miles Davis, and Miles Davis’s reputation preceded him. He was the “Prince of Darkness.” Word was that he didn’t like white people. One heard that he turned his back to audiences. So, with my knees knocking, I went to interview Miles Davis. It turned out very well, and since I had a transcript of the interview, a book about Miles seemed to make sense, but rather than another book on Kind of Blue, I suggested a book about the three geniuses at the center of the recording – Miles, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans – that would take the focus of looking at them as men and musicians before, during, and after their making that greatest jazz album of all time. Scott agreed it was a good idea and told me to “go do it.” So, I went and did it.

JJM Talk a little about the state of jazz prior to this recording…

JK Jazz was a keystone of American culture from the beginning of World War I and for the fifty years after that, and in the late 1950’s, when Kind of Blue was recorded, people like Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Miles Davis were household names to many people. It was a time when every big and medium-sized city in the country in the United States had a newspaper, many of which had music columnists and critics who wrote about jazz. It was also a time when you heard music like Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington’s “Take the A Train” and it felt like a kind of “national” music.

Dizzy Gillespie, 1947

.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Parker, 1947

Jazz of course went through many transformations. At the very beginning and through World War II it was dance music played by big bands, but for a variety of reasons the war era killed the big bands, and the groups got smaller and smaller, opening the door to the genius of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and their creation of bebop. This music wasn’t dance music, it was for sitting in a club or concert hall and listening to it.

So, bebop was not for everybody, and it diminished the audience somewhat. It was a complicated music, comparable, say, to cubism in that it outraged and confused a lot of people when it first came along. It wasn’t the sweet melodies that people had been used to hearing through the big band swing era. Also, it could be said that bebop was deliberately built by these genius Black musicians because they wanted something that was theirs alone at a difficult time for Black people in America, and it was a music that sang out independence. The musical reaction to bebop that followed – “hard bop” – was more lyrical and was more related to blues and gospel.

In the late 1950s, something else begins to come along, including Ornette Coleman and “free jazz,” which really freaked people out. And when rock and roll hits, hell is visited upon the world of jazz and everything begins to change. When the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan on February 9, 1964 – two and a half months after the Kennedy assassination when the country is pitched in gloom – they brought sunlight to the country with something new and gorgeous and magnetic and infectious, and the next morning every teenage boy in the United States who’d been struggling to learn how to play the trumpet or the saxophone goes out and buys an electric guitar, because all he needs now is three chords and he can be like the Beatles.

JJM Miles Davis was such a centerpiece of the era before Kind of Blue, and the one following it as well. And one of the things the jazz world learned about Miles early on is that he was the embodiment of “cool.” The definition of “cool” is widely understood now, but what did “cool” mean in the mid-1950’s, prior to Kind of Blue?

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Lester Young, 1946

JK There is no absolute definition of “cool,” and it meant a number of things to a number of people. We think we know what it means. We should begin by remembering that it was very probably the great Lester Young – the “President” of jazz – who created his own idiolect that he would share with friends, and it is very probable that he coined the word “cool” as a term of approval. Anything “cool” was good. But “cool” also came to have several different meanings – including in the world of drugs, which a lot of jazz musicians became exposed to, especially following the example of Charlie Parker. It could be used as a term to describe someone who might be wearing sunglasses because the light is hurting his eyes while he’s on heroin, or it could be he is wearing them just to look “cool” in a way that is removed. So “cool” meant different things to different people, but it’s a word that has stuck around. A lot of us, including myself, still have a good feeling about using the word “cool,” and I continue to use it as a term of approbation.

JJM And of course there is the Miles Davis album Birth of the Cool…

JK Yes. That isn’t what the album was called when it was released. It was created by Gil Evans (no relation to Bill Evans), a great Canadian composer and arranger who very quickly found a friend for life and a musical compatriot in Miles. This album was a new kind of jazz that married jazz and European classical music. It was not improvised – it was written down, arranged, and sounded very different from the improvised jazz of Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins and all the others who were improvising while soloing – and not everyone liked it. Dizzy Gillespie hated it at first. He would eventually feel different about it, but at first he felt that it didn’t have enough heat in it, and that it lacked the passion of improvised jazz.

Getting back to Miles and “cool,” he grew up in an upper middle-class environment in East St. Louis, the son of a prosperous dentist. He grew up riding horses and often wore Brooks Brothers suits. So, he comes to New York as a young man looking very sharp and crisp and clean in these suits, buttoned down shirts and neckties. I tell a story in the book about how the great Dexter Gordon corners him one day and — at six foot six, towering over Miles, who was five-seven — tells him that he can’t be dressed that way if he wants to look like a jazz musician – that it isn’t hip at all. So, there was Miles, thinking he was very cool, being reproached by an important fellow musician for not looking cool.

photo by William Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Parker and Miles Davis (with pianist Duke Jordan, bassist Tommy Potter, and drummer Max Roach); New York, 1947

As we now know, Miles came to be the definition of “cool,” but that has its own complicated roots. For one, Miles didn’t face the audience a lot of the time when he was on the bandstand, and people thought he was being arrogant, hostile, and removed, but Miles and the musicians who played with him have said that while his back was turned he was making gestures only they could see which meant that, in essence, he was conducting the musicians in the band. So, was that “cool?”

And, while Miles gained a reputation during the 50s as being the essence of “cool,” let’s not forget that for the first half of that decade he was addicted to heroin. He was in very bad shape, often disheveled and dirty, and couldn’t get signed to a major label due to his addiction. That was not “cool,” so his reputation really gathered speed once he kicked heroin, and once he played that memorable set of music at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival which led to his being signed by George Avakian of Columbia Records, the biggest record label in the world at the time. His records begin selling and he is making money for the first time in his life.

JJM So, the “cool” Miles became evident and well known. What about John Coltrane and Bill Evans? What was their public image before Kind of Blue?

New Jazz Conceptions (1956) [Riverside]

JK Evans was a nerd. He was white and wore glasses that made him look as if he were a high school science teacher. He came from New Jersey and was training to be a classical pianist but he fell in love with jazz and went to New York determined to make it as a jazz musician. Miles heard him playing at the Village Vanguard and asked him to join his band, and when Miles asked you to join his band, you joined his band. So, Evans joined Miles in 1958 and began to get blowback immediately for being the only white guy in the band. Black musicians hated that, so Evans is feeling dismissed all around, and he’s also feeling out of place in a lot of ways – not just for being white, but also for being uncool. To deal with it he begins to take drugs, and it’s awful to say, but he set about becoming the biggest junkie in Miles’ band, with the thought that this could make him hip.

Coltrane was a beautiful man. He was a genius. He was a great musician. And we could use the word “cool” in approving of Coltrane and saying all those great things about him, but there was never anything cool about him. He was a deeply emotional, earnest man who felt things intensely and showed what he felt. He was also a very sad man who experienced a lot of loss in his life. He lost his father before he turned 13, and he also lost other important relatives. So, there was always a deep feeling of sadness about Coltrane.

John Coltrane on the cover of his 1957 Prestige album, Coltrane

When he first joined Miles’s band in 1955, nobody knew who John Coltrane was, and nobody understood why Miles had hired a guy who’d previously been playing saxophone in the rhythm and blues bands of Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and Earl Bostic while at times – much to his embarrassment – walking saloon bars. There’s nothing cool about that, and there was nothing cool about the way it made him feel. But while others questioned why Miles had Coltrane join his band, Miles knew why – because Coltrane was a genius and, as Miles said, the fastest, loudest saxophone player he had ever heard, which Miles loved. He was also extremely serious about music, and earnest about understanding it technically. But Coltrane immediately begins driving Miles crazy by asking him questions about what they’re going to play and how they’re going to play it. Miles didn’t like to talk about the music. There’s a famous story about Miles and the great saxophonist George Coleman, who was in one of Miles’s bands after Coltrane left. One night after a gig he hears Coleman practicing in his hotel room. Miles bangs on the door furiously and when Coleman opens the door Miles screams at him, “I pay you to practice on the bandstand!” He wanted his musicians to be spontaneous on the bandstand. He didn’t want to talk with Coltrane about theory or European composers – he wanted his musicians to understand all that in a visceral way, the way he did.

I realize I’m not giving you solid, crisp, simple answers to the question of “cool.” I would say that we can look at everybody in Miles Davis’s sextet of 1958 and 1959 and conclude that these were absolutely “cool” musicians in the sense that they were great musicians. But were they “cool?” Were they removed emotionally? You know that Miles often seemed that way, and that emerged in many ways, especially in his sound, which can be identified as Miles’s sound instantly, right? You hear the trumpet and know it’s him. What is it about that sound? It was a combination of warmth and distance that only Miles could create. There is a haunted quality to his music, and yes, I think you could use the word “cool” there, and while it’s not the only term of approval to use for his great music, it does apply in a way unique to him.

JJM What other challenges did Miles and Coltrane have early on while playing together?

The cover of the compilation album The Best of Miles Davis & John Coltrane (1955-1961) [Columbia]

JK A big challenge was that Coltrane himself was still a heroin addict when he first joined Miles’s band. And, like other heroin addicts who were also musicians – including Miles, at an earlier time – Coltrane was frequently late to gigs or absent from gigs without explanation, often showing up disheveled or dirty, in a wrinkled suit he had been wearing for five days straight. Or he’d pick his nose on the bandstand and do other disgusting things like that, mostly because heroin addicts have lost themselves to the drug – they are servants to it and become miserable creatures. So that was a huge challenge for Miles, and in fact he punched Coltrane in the stomach and fired him during his first tenure with the band because was so angry at Coltrane for being addicted. I think in a lot of ways Miles was projecting onto Trane some of the anger he still felt at himself for having once been addicted.

JJM And…what musical challenges did Miles and Bill Evans have, and how did they work together?

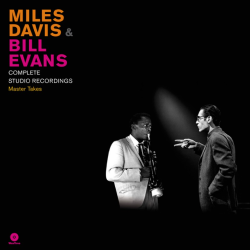

The cover of the compilation album Miles Davis & Bill Evans: The Complete Studio Recordings [Waxtime]

JK I would say that at the beginning it wasn’t challenging at all for them – it was a pure romance. Evans had come to New York in 1955 determined to make it in jazz. He scrambled for a living, playing a lot of weddings and dances and bar mitzvahs, and then managed to snag a gig at the Village Vanguard, playing in between sets by the Modern Jazz Quartet, who were one of the biggest acts in jazz at that time. The Vanguard is a small, intimate space that serves food, and when the MJQ played the audience was reverent and dead silent, but when it was Evans’s turn to play the piano, the club gets filled with the sounds of clinking dishes and silverware and people talking among themselves. Evans is having to undergo all this, and then one night amid all the noise of the club, he looks down toward the end of the grand piano and sees the eyes of Miles Davis staring at him, listening intently. A week later, to Evans’s astonishment, Miles called him up out of the blue, and told him that Evans would be joining his band – he didn’t ask, he told him. Why was Miles so emphatic about this? Because Evans brought something to jazz that hadn’t been there before. As great a player as John Lewis of the MJQ was, Evans brought tonalities, textures, harmonies of modern, western classical – of Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky and Ravel, in particular – to the playing of jazz, sounds nobody had created before. Miles was a huge fan of modern, western classical and the composers I just mentioned, and especially of Ravel, and he’s hearing this in Evans’s playing.

So, Miles falls in love with the piano playing of Bill Evans. There were even times during Evans’s time in the band when Miles – who was always a tortured soul – couldn’t sleep and would call Bill at three or four o’clock in the morning and ask him to just play. Bill would put the phone on the table next to the piano and play and Miles would listen and relax until he was able to fall asleep. He later said that he planned Kind of Blue around the piano playing of Bill Evans.

JJM Beyond the issue of race, how did Coltrane and the other members of the band take to Evans being a part of it?

Dave Brinkman / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cannonball Adderley, 1961

JK I know that Cannonball Adderley is on the record for having had a huge admiration for Evans. Cannonball was a brilliant musician, and a brilliant man. He was thoughtful, articulate, and versed in all forms of music, which meant he went through some of the same things with Miles that Coltrane did when wanting to talk about music theory and the underpinnings of the music. As we know, Miles didn’t want any of that. Cannonball’s parents were both college teachers, so coming from that academic background and knowing so much about all kinds of music, he greatly admired Bill Evans.

I’ve done a lot of research on this topic and it is still not clear to me what Coltrane thought of Bill Evans. That’s a big statement to make. It has been suggested by some that Coltrane didn’t like Evans, but I don’t know if that’s true. It’s hard for me to believe that Coltrane wouldn’t have liked – if not loved – Evans’s playing, but in all the Coltrane interviews I’ve read, he never mentioned Bill a single time. I find that sort of striking in itself, and I’m not sure what it means, if anything. It could have just been Coltrane’s shyness, his being to himself in a lot of ways. In the end I just don’t know if there was much of a relationship between the two of them.

As for Paul Chambers, to know what he thought of Bill Evans all you have to do is listen to the very beginning of “So What” and you will hear this marriage between his bass and Bill’s piano. The enigmatic chords that Evans plays paired with the mysterious notes Chambers plays are so gorgeous that you just know there is great mutual respect between those two musicians. Of all the musicians I’ve mentioned, I would say that while Jimmy Cobb was a wonderful, important, sought after drummer, he was not on the plateau of musical greatness that the other five members of the band were on, which may be a harsh statement to make. And, I don’t really have an answer for how Jimmy Cobb felt about Evans being in the band.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to “So What,” from Kind of Blue

.

JJM Sixty-five years since the album’s release, we of course have the benefit of understanding the greatness of Kind of Blue. How was it received critically when it was initially released?

JK Like a lot of great art, it was misunderstood when it first came out. There were a number of critics and jazz musicians who accused the album of being too quiet, too restrained — it wasn’t forceful enough, it didn’t swing. “Swinging” is not the point with Kind of Blue. Miles used the word “swing” in a similar way that many people use the word “cool,” as a term of approbation. Wallace Roney – who was Miles’s only protégé ever – told me that the first time he went to meet with Miles at his home, the very first words Miles uttered were “Clifford Brown doesn’t swing.” Go figure. Why did he feel the need to say that about the great Clifford Brown?

So, Kind of Blue was a thing all its own, and that is what has really made it endure for the last 65 years. The word “timeless” is way overused these days, but that album is truly timeless because it is literally outside of its time. It was recorded in March and April of 1959 but doesn’t sound like 1959, and it doesn’t sound like 1954 or 1969 either. It doesn’t sound like any time, it is just its own thing, and people had trouble figuring that out at first, but then over the years more and more people began to realize how wonderful listening to this album made them feel.

JJM It is one of those albums that people remember when and where they got it. It is timeless and memorable from that standpoint also.

JK Yes, that’s right.

JJM Shortly after the recording of Kind of Blue, the band basically broke up. Coltrane went off and recorded Giant Steps a few weeks later, and Bill Evans formed his trio…

JK Yes, they all went their own ways. It was a centrifugal band in some respect — Evans and Coltrane and Cannonball all wanted to lead their own groups, and they went out and did that.

JJM And in the immediate aftermath of the recording, Miles had the challenge of replacing all these guys…

JK Yes. Wayne Shorter, who had been unavailable for years, joins Miles. Then he gets Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, and Ron Carter, and together this second great quintet makes new sounds and music that are altogether wonderful. But even as this is happening, due to rock and roll the audience for jazz is diminishing rapidly – like watching water swirling down a drain. Rock and roll basically dropped a neutron bomb on jazz. Miles found a way forward. He and Coltrane and Evans were all able to make a good living because they were superstars of the music. They were able to continue on through the 1960s – although of course Coltrane only lived until 1967 – because they could get gigs. Many other fine jazz musicians had a hard time making a living during the 1960s and 1970s, but Miles being Miles found a way forward and, since he couldn’t beat rock music he joined it, and jazz/rock fusion was born.

JJM Of Coltrane, Miles and Bill Evans, who would you say showed the most musical growth during their post-Kind of Blue years?

Conversations with Myself (1963) [Verve]

JK Well, it may be easy to say that Evans grew the least because he kept to the trio format and played a lot of the same songs and sets throughout the rest of his career until his death in 1980. When I tendered this opinion with the brilliant pianist and composer Jon Batiste, whom I interviewed for my book, he immediately disagreed with me. He pointed to the album Conversations with Myself where Evans plays double tracks, meaning he basically played in duo with himself. Who else in jazz ever did that? Other musicians I talked to felt that even though Evans’s playing remained similar, and that the trio format basically stayed the same, that he went deeper and deeper into the textures and harmonies of the music he was playing. This was vitiated by his drug habit, which went from heroin to methadone to the injecting of cocaine. Many musicians used cocaine, but it is very hard to find others who actually shot it up. Some of them felt that it made Evans speed up tempos, that it ruined Evans’s miraculous touch.

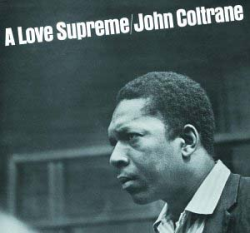

A Love Supreme (1964). [Impulse!]

.

Interstellar Space (1967) [Impulse!]

Meanwhile, Coltrane goes on a space voyage, right? There’s Giant Steps and then there’s A Love Supreme, and then there’s Interstellar Space, and suddenly Coltrane is out there playing saxophone in a way that nobody could ever imagine, and finding extensions of chords that nobody had ever thought of before, and playing long, long, riffs where even he didn’t know where he was going. Musicians like his stalwart accompanist McCoy Tyner began to feel that Coltrane was just playing for himself, and that’s a tough way of putting it, but Coltrane was, in a sense, playing for himself. He was exploring outer space with his music. Very late Coltrane is hard to listen to, and many of the musicians I interviewed said that it should be hard to listen to. That it is all the greater for being difficult music. A lot of musicians felt that way too about the titans of free jazz, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler and Cecil Taylor — that their music wasn’t melodic or easy to listen to, but it contained greatness.

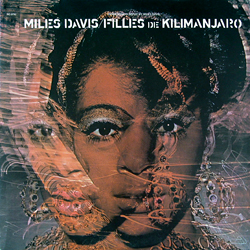

Filles de Kilimanjaro (1968) [Columbia]

.

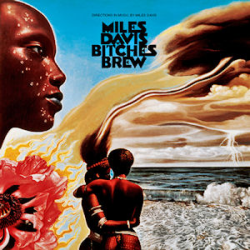

Bitches Brew (1969) [Columbia]

So, Coltrane went very far and Miles went off in many different directions. He made beautiful albums like Filles de Kilimanjaro and Bitches Brew in which there is a lot of electric instrumentation. But the cold truth is that Miles wanted to sell records, and he saw these young rock and roll musicians who, musically speaking, weren’t even a wart on his posterior but who were making 20 times the money he was. They played their electric instruments in huge arenas, and Miles wanted some of that action. So that was a lot of the impetus for his taking on the instruments of rock and roll, and he made a lot of memorable electric music but the problem with him during this era was that while he was advancing musically and intellectually, his physical energy was diminishing and his body was letting him down. He had sickle cell anemia. He had terrible pain in his joints. He had a hip replacement that didn’t work — that caused him awful discomfort. So, he self-medicated with alcohol and cocaine.

There was then the period where he sat out music entirely for six or seven years, but then he comes back in the early 1980s and starts to do something new and different, playing Cyndi Lauper’s hit song “Time After Time” and Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature” — tracks that some people love and others hate, but they sold records. There were a lot of different strands to Miles’s career in the decades after Kind of Blue. He did a lot of wonderful stuff, and he did a lot of less than wonderful stuff, and all the while, unfortunately, his chops as a trumpeter were diminishing sharply. So, through a lot of his latter career he was just blowing a note or two here or there as opposed to anything extended. And a lot of the time he was playing an electric keyboard instead of the trumpet. And though he lived to age 65 he was a very, very old and weak and diminished 65 by the time he died.

JJM Before I ask a final question, I just want to briefly share my own first experience with Kind of Blue. I heard it in a record store in Berkeley in the late 1960’s when I was about 14. While flipping through the record bins – probably with the intent of buying a Doors or Beatles or Santana album – I couldn’t help but notice the music the clerk was playing in the store, which was just so brilliant. I had some exposure to jazz at that time in my life and was intrigued by it, but I hadn’t heard anything quite like that. I asked the clerk what we were listening to and he handed me the record, which I was mesmerized by, and I bought it on the spot. That moment absolutely changed my life. From there I dug deep into Miles, Coltrane, Evans, Cannonball Adderley, and all their albums, the albums of the players on their records, and on and on. In many ways the impact of that album set me on the path to our having this conversation.

So, it is an album that impacts people, and the last question I have for you deals with its impact. You wrote in your book: “The album’s powerful and enduring mystique has made it widely beloved among musicians and music lovers of every category: jazz, rock, classical, rap.” What are the impacts of Kind of Blue on contemporary music and musicians, and how is it still being felt among musicians of the last 5 – 10 years?

JK It remains revered among musicians, and is still seen by them as a “one-off.” They say there will never be another Kind of Blue. It gets sampled now and then by contemporary musicians – for example, I was listening to a track by the wonderful Robert Glasper the other night which sounds like a combination of Miles and Glasper, and Miles is heard talking in the background. That is a simple reminder that Miles remains a very powerful influence in the culture at large. You’ll find people who don’t even know his music that much, but when you say his name they know that there is something very hip, very cool, and very important about it. And musicians revere Miles — they know that nobody like him will ever come again, and nothing like that album will ever be recorded again. All the cosmic cogs and tumblers kind of lined up in the spring of 1959, during a time when Miles felt that jazz had gotten too complex, with too many chords and too many notes. He wanted to simplify the music. He was interested in modes – which are really just scales. He felt that you could build a great jazz tune on one chord instead of on five or six or seven chord changes.

He remembered being a boy at his grandparents’ farm in Arkansas, walking home at night along a deserted country road and hearing in the distance the almost ghostly sound of Black churchgoers singing gospel songs in the night, and he wanted some of that goosebump-inspiring spirit, this quiet majesty, in the album that became Kind of Blue. And I think there’s something about that quiet majesty that makes that album unreproducible, unduplicatable. It’s the thing that makes it endure and makes it continue to sell and continue to strike people with awe in the same way that it struck you when you were that 14-year-old in the record store in Berkeley. It was a quiet majesty that only Miles could figure out how to create, and it’s there for all time.

.

.

“Man, sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself.”

-Miles Davis

.

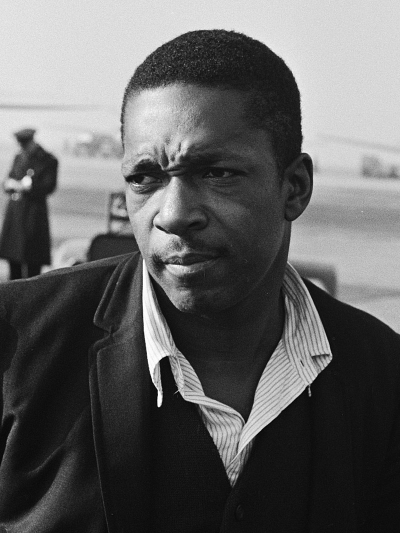

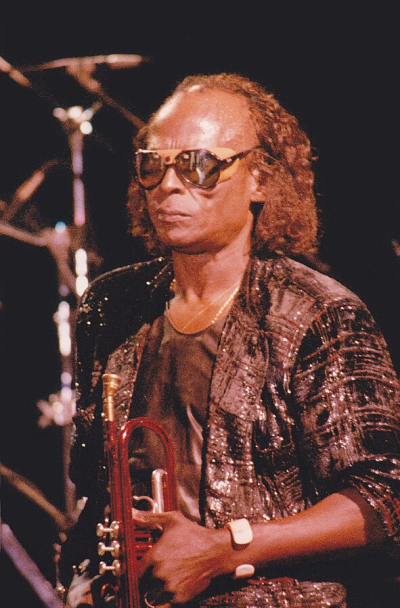

Tom Palumbo from New York City, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Miles Davis, c. 1955/1956

.

Steve Schapiro, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bill Evans, 1961

.

Gelderen, Hugo van / Anefo, CC0,, via Wikimedia Commons

John Coltrane, 1963

.

Dr Jean Fortunet, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Miles Davis, 1987

.

.

_____

.

.

3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the Lost Empire of Cool , by James Kaplan [Penguin Random House]

.

.

About James Kaplan

James Kaplan’s essays, stories, reviews, and profiles have appeared in numerous magazines, including The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, Esquire, and New York. His novels include Pearl’s Progress and Two Guys from Verona, a New York Times Notable Book for 1998. His nonfiction works include The Airport, You Cannot Be Serious (coauthored with John McEnroe), Dean & Me: A Love Story (with Jerry Lewis), Frank: The Voice, and Sinatra: The Chairman. He is a 2012 Guggenheim Fellow. He lives in Westchester, New York.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview took place on July 31, 2024, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

___

.

.

.

Click here to read our interview with James Kaplan on his book Irving Berlin: New York Genius

Click here to read my 2002 interview with Ashley Kahn, author of Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.