.

.

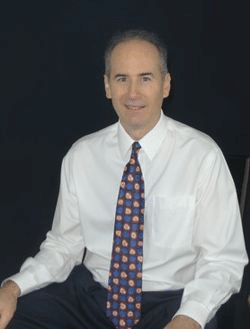

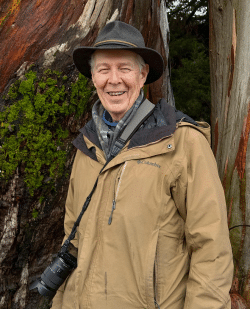

photo by John Amin

Gary Carner, author of Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer

.

.

___

.

.

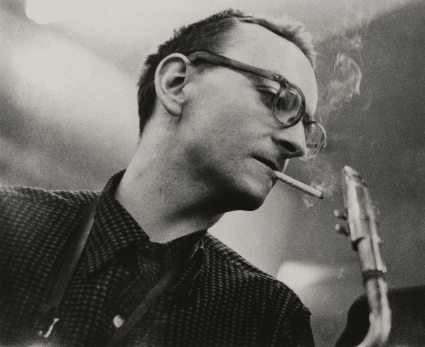

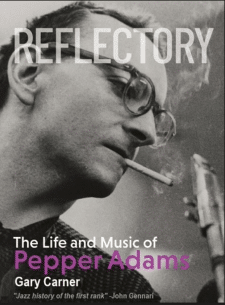

Courtesy of the Estate of Pepper Adams

Pepper Adams, 1957

.

___

.

…..The stellar, innovative baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams, known and revered for his hard-swinging bebop style, disliked musical cliches and consciously worked to avoid them. “If I do play one,” Adams once said, “I try to find a way to invert it, put it in the wrong key, or run it across the wrong bar—do something funny with it.”

…..With that attitude, that compulsion to be original, it seems a sure bet that Adams would be pleased with how his story has been told by author Gary Carner, who has also consciously avoided cliches in his biographical study of the late, great Park “Pepper” Adams. Carner, for example, has in places inverted the chronology of Adams’s storyline, and completely eschewed the trite pitfalls of so many jazz bios, which tediously follow their heroes from club to club and record date to record date.

,,,,,Carner had a friendship with Adams during the two years before his death in 1986, yet that relationship doesn’t get in the way of his taking a candid look at Adams’s life, examining his personal foibles and challenges along with the consistent majesty of his playing and composing.

…..Adams recorded prolifically during his thirty-year career and was featured as a sideman on some 800 recordings, including twenty as a leader. As a sideman, he was hired by a plethora of jazz giants, including Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, Donald Byrd, John Coltrane, Barry Harris, Johnny Griffin, Hank Mobley, Lionel Hampton, Thad Jones/Mel Lewis, Quincy Jones, Stan Kenton, Benny Goodman, Duke Pearson, Sonny Stitt, Elvin Jones, Chet Baker, Dizzy Gillespie, and the list goes on and on.

.

Here is a video of Pepper Adams in action, performing in England in 1981, playing his original composition, “Dylan’s Delight,” with John Horler, piano, Jim Richardson, bass, Trevor Tomkins, drums.

.

…..Spending formative years in Detroit, Adams also distinguished himself by being accepted into the Black jazz community, rare for a white musician. During his time in Detroit, Carner reports, he was usually the lone white musician in black bands. Further, during the golden years of Blue Note Records, Adams was the only Caucasian to be featured on scores of albums during the 50s, 60s and into the 70s, although never as a leader.

…..Referring to the many recordings he co-led with trumpeter Donald Byrd, jazz writer Gary Giddins wrote, “When Pepper made those records, he really pushed the baritone into the middle of the hard-bop thing.”

…..He was indeed a trailblazer on his horn, adapting the fleet virtuosity of altoist Charlie Parker to the bigger, more cumbersome horn. He ultimately became, as a result, the most influential baritone saxophonist in modern jazz, inspiring such top-tier players as Nick Brignola, Gary Smulyan, Ronnie Cuber and Hamiet Bluiett.

…..Adams benefited from the mentorship of numerous musicians during his formative years, including Harry Carney, Rex Stewart, Oscar Pettiford, Lionel Hampton, Wardell Gray, Skippy Williams and others. Subsequently, while he did not teach formally, he in turn served as a mentor to others, notably trombonist Curtis Fuller. “One of Adams’s littlest known influences on the world of jazz,” notes Carner, “is his mentorship of Fuller, and how, by doing so, he influenced the lineage of modern jazz trombone playing. ‘Coming up with Pepper on the Detroit scene,’ said Fuller, ‘he inspired me, taught me to reach, [to] try to get more out of the trombone without the slide.’”

…..Adams was held in very high esteem by his fellow musicians. He was admired for his intellect as well as his musical talent. He and Charlie Parker were friends who hung out to discuss books and classical music. The late pianist Hank Jones, who knew Adams from his Detroit days and recorded with him numerous times during his career, said about Adams, “With the way he played the horn, Pepper was as close to a genius as you can find on earth. He was a giant. His ideas,” Jones said, “were endless, absolutely endless and varied. Every chorus was better than the one before.”

…..Adams’s career, Carner writes, “can be measured by a long, slowly ascending arc of success that increased exponentially once he left the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. Without a doubt, his first six years as a traveling soloist were triumphant—a time when he burnished his legacy as a virtuoso performer and distinctive composer.”

…..During those years, Adams garnered multiple Grammy nominations and was beginning, Carner writes, “to make a decent living and the public was becoming more familiar with him…His career was on the upswing. Had he lived just another few years, it’s entirely possible that a large record label might have swooped down and signed him, just as Verve did with fellow Detroiter Joe Henderson.”

…..Adams, as Carner observes, was a man of distinct contrasts—a confident musician who could match musical skills and wits with the very greatest and yet was somewhat timid off the bandstand. And, while his music was rich with deeply passionate expression, he was often perceived as someone who had difficulty expressing his inner feelings.

…..Carner’s involvement with Adams began when Pepper agreed to be the subject of an oral history for a master’s degree thesis Carner eventually wrote while at City College of New York. “I was a 28-year-old grad student,” Carner writes, “a passionate jazz fan who was trying to interest a jazz musician in working with me on an oral history to satisfy my thesis requirement. Adams, I soon learned, was an ideal subject: a major soloist who, from the late 1940s onward had played with virtually everyone in jazz.”

…..Initially the two planned to co-write Adams’s autobiography but Adams was diagnosed with cancer that would soon cut his life short at age 55. But Carner remained focused on his goal of doing justice to the genius of Pepper Adams by sharing his story and achievements with the world. That goal would occupy Carner for most of the next four decades, during which Carner interviewed some 250 people who had known Adams or played with him. His project just kept expanding. First, he published an annotated discography, Joy Road, followed by a series of six CD projects covering all of Adams’s forty-some compositions. These were followed by a 400-page biography, Reflectory, published in an eBook format and including more than 400 cuts of music, more than half of them previously unreleased. This Herculean effort was capped with his latest release, a paperback biography, Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer, a 240-page abridged version of the earlier biography.

…..On the release of Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer, Carner spoke with me about his book and his decades-long dedication to the genius of Pepper Adams. Our conversation was recorded on December 3, 2023.

Bob Hecht

Contributing Writer

.

.

___

.

.

.

Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer, by Gary Carner

.

BH Welcome, Gary. Thanks so much for talking with us about the great Pepper Adams. Full disclosure: I come to this somewhat biased, in that I consider Pepper to be a national treasure.

GC Thanks for the opportunity, Bob. It’s not every day that I speak to somebody who knows anything about Mr. Adams.

BH I am not alone in being impressed by the single-minded dedication you have shown toward your subject. Mark Stryker, the author of Jazz from Detroit, wrote this about you: “Gary Carner has been stalking the life, music and legacy of the brilliant baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams…with an Ahab-like obsessiveness for 37 years. The great news for the rest of us is that Carner has landed his whale.” That’s quite a testament to what you’ve done.

GC Mark’s a friend and he was one of my readers, and yes, he was very, very gracious in saying that. I really appreciate it.

BH It strikes me that, in a sense, you’ve built a kind of monument to Pepper Adams in words and sounds. I doubt there’s a parallel in all of jazz of such a dedicated focus by one individual over such a long time. Congratulations.

GC Thank you. And it didn’t start that way. I can tell you that. My initial interest was just working with him and getting my master’s thesis done at City College. And then one thing led to another. I mean, he’s just such a phenomenal musician, and the deeper I got into it, the deeper I wanted to go. Had he not gotten sick, we would have done a co-written autobiography. But he got cancer, and everything changed. There were just so many questions I would have liked to ask him, but he was gone in ‘86.

BH Well, you were lucky to have had that bit of time with him, I think.

GC Absolutely. If you look at the website, I have a few postcards that he sent me from his travels, which I was so proud to receive. And all these materials are going to William Paterson University. Some are already there. I have his charts and a variety of memorabilia—photographs and such—so that future researchers can do more work. But now I am finished.

BH I imagine it’s something of a relief to be done with this massive project.

GC You know, it is. It took me four years to write the biography. It took me something like 32 years of research. It took me four months to edit it down into paperback. So, I’ve taken a bit of a break from it these past few months. Before this phone call, I went on to the eBook (Reflectory) and listened to a few recordings of his to kind of get juiced up and in the mood. And, you know, listening to Pepper’s solos again, they are just so, so impressive; brought tears to my eyes.

BH His music is always so fresh. Please give us a little background on you and on how this all began.

GC Sure. I was 28 years old when I met Pepper Adams. I was a dedicated concert and clubgoer by that time, and record collector as well. I graduated from Fairleigh Dickinson with a fine arts degree, where I studied with a very gifted guitarist and Renaissance lutenist, John Varner. I ended up studying with him privately for seven years. I was playing classical guitar and Renaissance lute, and we were starting to edge into a recorder as well. But John passed away. He taught me so much about music. I could speak endlessly about him. I then decided I wanted to get more musical chops. I went to City College of New York (CCNY) and took a year’s worth of extra music classes. Harmony, ear training, things of that nature.

At CCNY I also happened to meet an English professor, Barry Wallenstein, a poet, and I studied writing with him. At that point I had already decided I wanted to write a jazz biography. I had no idea who I was going to treat but I was very much inspired by Brian Priestley’s biography of Charles Mingus. I was a big Mingus fan. I took two semesters of jazz history, too. They had a very robust jazz program there. The first semester was with John Lewis, the second was with Ron Carter. So, toward the end of the year, Barry Wallenstein said to me, ‘Why don’t you come and get a master’s in English?’ I told him I would love to, if I could do a thesis on a jazz musician, like an oral history or something like that.

I then shifted from music classes that year to a master’s in English. And then, once I finished the oral history, which essentially is a thumbnail biography, I decided I wanted to go for a Ph.D. At that point, I met Lewis Porter, who invited me to come study with him at Tufts. I was his only graduate student, starting in 1985. I was there with him for three semesters before he left to go to Rutgers. I had unfettered access to him, and he really shaped me as a researcher. It was really great. So, as I mention at pepperadams.com, John Varner shaped me as a musician. Barry Wallenstein shaped me as an author, and Lewis Porter shaped me as a musicologist.

BH You got the trifecta.

GC Right. Things just kind of evolved from there. After the first year at CCNY, it became incumbent upon me to find a musician, so I sent out five letters to musicians that I had heard. They included trumpeter Red Rodney; multi-instrumentalist Ira Sullivan; altoist Phil Woods; Eric Kloss, the blind saxophonist from Philadelphia; and Pepper Adams. I don’t know if I had necessarily heard Pepper live yet. But I was very impressed with his solo on “Mr. Jones,” on the Elvin Jones album of the same title.

…..My letter to Pepper went to Radio Registry, which at that time was the place where mail was received for musicians in New York. This was seven years before the Internet and several years before everybody had answering machines. I didn’t hear anything for a while. My girlfriend, who became my wife, ran into Red Rodney at a nearby A&P supermarket and she told him, ‘Oh, my boyfriend really wants to talk to you!’ And I ended up meeting him at his house in New Milford, but he said he was already working with somebody in DC. Then, suddenly, I heard from Pepper Adams who said, ‘Hey, I’d love to meet you. I’ve been laid up with this accident, but as soon as my orthopedist frees me to get around, come on out to Brooklyn and we’ll meet.’ (He had recently had his leg crushed in a freak car accident.)

…..The time came when he was ready, and I went out there. It was a hot Saturday in June. I didn’t know he was a drinker, but, somehow, I had the intuition to bring a bottle of sparkling wine. We were chatting about this and that, and then I saw his mood kind of lighten up a little bit when we started drinking, that he became much more convivial. We had a lot of similar interests, either politically or socially, and I knew a lot of the classical music that he was listening to. He loved Arthur Honegger. (He and Charlie Parker had that in common, too.) And I was also familiar with some of Honegger’s music, as I was starting to collect classical records. And then, when Pepper found out that I knew Thad Jones’s son, Bruce, who’d been in my seventh-grade class, that was sort of the clincher. Now it was like three degrees of separation. And he said, ‘Well, yeah, let’s set up something.’

…..A few weeks later, I went out to his house with my trusty Sony microcassette recorder. We met several times that summer, and I ended up getting 18 hours of interview material. But seven months later, Pepper went to Sweden, and his cancer was discovered. So, everything shifted. I realized that I had to work on this book. After he passed away, I decided to interview everybody who had known him or recorded with him.

BH And that worked out to be 250 people that you interviewed, right?

GC Right. Now, some of them were short interviews, but I spent the good part of a day with Tommy Flanagan, and talked at some length with Barry Harris, David Amram, Ed Xiques, Bill Perkins, Mel Lewis, Hank Jones, Don Friedman, and Jimmy Heath, to name just a few of the 250 interviewees.

…..But, I’ll tell you, Bob. I was very intimidated. Pepper is, as you have noted, a national treasure. He’s a monolithic figure in American arts, as I see it. He was incredibly well read; he had a brilliant mind. I wanted to do something that I thought was worthy of him.

BH Well, you’ve done a magnificent job. And life is so funny, isn’t it? I mean, the randomness of it. Your last several decades would have been very different if Red Rodney had said he would have loved to have done the interviews—that would have been a very different story.

GC That’s right. Pepper was so deserving and in need of this kind of monumental treatment, I think, because he really was a genius.

BH He was. And I came to appreciate that even more after recently re-reading Reflectory, and then reading Saxophone Trailblazer. That title is so apt. Although I knew and loved his music, I hadn’t completely understood just how innovative he was, how he turned around the baritone saxophone in modern jazz.

GC Oh, yeah. Absolutely. So very much an innovator.

.

MUSICAL INTERLUDE: Here is a prime example of Pepper Adams’s playing and composing. It is his composition “Ephemera,” which he cited as his favorite original tune. It features three of his colleagues from the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra: Roland Hanna on piano, George Mraz on bass and Mel Lewis on drums, and of course Pepper on baritone sax.

.

BH Reflectory, the eBook version, with its multitudinous hyperlinks to recordings, makes it such a rich experience. I’ve gone through it multiple times, just to go to the various sound files.

GC I’m very, very proud of the book because it is, as you say, so much richer. It’s the book I always intended to write, is twice the length of Saxophone Trailblazer and contains so much more detail about so many aspects of his personal and professional life. But I’m also very grateful to Excelsior Editions and SUNY, the State University of New York, for being interested in putting this out as a paperback. The goal was to get as many people aware of Pepper’s career as possible, and to get it into print form is very important.

BH I’d like to mention, too, how tickled and impressed I was by the series of quotes in your epigraph, which go to the heart of jazz, real jazz. You lead off with the great Lester Young quote, “You got to be original, man.” And then, in the book, echoing that, there’s the little bit of advice Pepper gave to his student, David Schiff, when he said, “You can mimic anyone you want, but you’ve got to get your own sound and your own style.” Pepper lived that, right?

GC Oh, yeah, absolutely. I’m glad you picked that up, because it delineated Pepper’s approach to playing and what he would have been teaching. His method is right there and is, like you said, ‘Be original.’ But also play on the outside. Don’t play linear, Play fourths and sixths. Play large intervals and play the blues like it doesn’t sound like the blues, so your individuality can come through.

….Another important experience that I had was with Benny Maupin, who was Herbie Hancock’s saxophonist for quite a bit. Benny helped me understand the importance of education in Detroit. For many, many years I didn’t really understand what made these Detroiters so unique. And finally, just piecing all these interviews together, it occurred to me that it was the whole background of Detroit. It was Grinnell’s, Detroit’s largest music store. It was the really strong educational foundation that they all had. It wasn’t just Cass Tech. It was everything about that city.

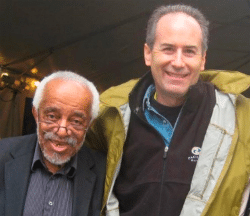

Pianist Barry Harris with Gary Carner

BH Some time back, I did an interview with Kirk Lightsey, who, of course, is one of the many great pianists to come out of Detroit. And he talked about the critical importance of the hangouts that Barry Harris had at his house, at least until Barry’s wife threw them out. That was an incubator.

GC Absolutely. And there were jam sessions at other houses, too, including Elvin Jones’s. I think it was the auto industry, which provided a tremendous amount of work for African Americans, that created this great entertainment industry, starting in the 20s.

BH We know that Pepper so loved Duke Ellington’s music. And you write about how he and baritone saxophonist Harry Carney from Duke’s band were quite close. It was wonderful to read that Harry deputized Pepper as his replacement in the Ellington band; something that never came to fruition, but what a testament to how highly he was regarded.

GC Yes and I didn’t know anything about that. Pepper revealed that to me. And that obviously says a lot about Duke’s and Carney’s appreciation for Pepper’s artistry. And then there was trumpeter Rex Stewart’s influence as a father figure for Pepper. When Pepper was told that Rex had passed away, he started weeping. Pepper was usually very very close to the vest with his emotions, so, obviously, it was a big blow to him. The other big blow to Pepper was the death of Wardell Gray.

BH The other aspect that I was impressed with, in reading about Pepper, was his initially embracing the baritone sax, which again confirmed his desire for originality. You write about how he looked at the landscape of the existing baritone players, and he said, “I saw it as a wide-open field, I thought I had a chance to do something entirely different,” that there was a whole lot that nobody had even attempted to do. And that, of course, was mostly springing out of Pepper’s being so impressed with Charlie Parker’s innovations. Would you describe how you start the book, recounting Pepper’s pivotal epiphany upon first hearing Bird live in Detroit.

GC Sure. I talk about how, as eighteen-year-olds, he and some friends went to the Mirror Ballroom in Detroit to hear Parker. It was quite a night. Pepper had been playing for about a year on the baritone. When he went to see Charlie Parker, that’s really where the lightbulb went off. I think Pepper was still trying to get a sound and a conception, and he was very much a classical music devotee. He was already very drawn to the whole 20th century harmonic landscape, to composers like Stravinsky. And then he heard Parker and said, essentially, hold everything. It’s an extraordinary moment. He’s there with two friends, one of whom, Oliver Shearer, was quoted as saying that he’d never seen anybody so excited in his life. Pepper was jumping out of his seat.

…..He realized that he could incorporate Parker’s approach and apply it to the baritone. Not copy his licks, but, rather, develop a personal style in Parker’s image. Some people were trying to do that already, such as Cecil Payne, but a lot of the musicians on the baritone were really not able to play in time. They were really huffing and puffing. Pepper had tremendous confidence that he could, in fact, be a virtuoso on the horn and play with a full sound but also play with the rapidity of pianist Art Tatum, whom he adored. Curtis Fuller told me that Pepper was playing Tatum lines. Pepper was able to do everything and had such a sophisticated time feel. He could play behind the beat, he could play on the beat. He had his own time.

BH You write, too, about Pepper’s use of dynamics.

GC The use of dynamics was very important to Pepper. Dynamics had been so big in the 30s and 40s but would then fall out of fashion with Coltrane. Pepper also sometimes used humor, musical humor, even ridiculous farce, as paraphrase. He really has become the model for all subsequent baritone players. He has lifted the level of playing on the instrument to such a high degree.

BH And Pepper had such a dry sense of humor. I love the story at pepperadams.com about him hanging out with Thelonious Monk and Doug Watkins one day. Pepper said of Monk, “Monk, Doug Watkins, and I are hanging out together, and he had a test pressing of a solo album that he had made. None of us had heard it before so we went to Doug’s and played it on his phonograph. We were sitting there listening to it. Monk looks up and says, ‘That’s a good record. You could give that to your grandmother.’ I said, ‘You couldn’t give that to my grandmother. She’s a Bud Powell fan!’ And Monk just kind of glared at me and then went back to listening to the music again. I don’t think he understood joking very much.”

GC That’s classic Pepper.

BH That’s dry humor.

GC Oh, very dry. That’s a great example of that.

…..I think his life changed when he got to New York, when he became much more of a drinker. And it was much harder to work. He wasn’t appreciated, and for 15 years of his life he didn’t record. He was dealing with situational depression because of it. And, finally, he got married. His finances improved and he got the courage to go out as a single. Those last six years or so, before he got ill and before the car accident, were really triumphant for Pepper.

CJohn P. McCrady, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Pepper Adams, 1978

BH Right. He made a lot of recordings as a leader, and his compositions were flowing out of him. Let’s talk about Pepper as a composer, because he was a wonderful composer as well as baritone player. His compositions are unique, very carefully constructed. You discuss his long involvement with Thad Jones and the mutual loves that they shared, and I found myself wondering if you think that Thad’s composing was a direct influence on Pepper’s composing.

GC Pepper’s use of bass and baritone paired together, with George Mraz, was possibly a Thad influence because Thad loved pairing the baseline with the melody line. I think that was probably a direct borrowing, albeit from Duke Ellington.

MUSICAL INTERLUDE: Here is another example of Pepper’s playing and composing, the composition, “Reflectory,” from his album of the same name. It is one of his most intriguing tunes, with the line played both in unison and as a sort of alternating round by baritone and bass. It features Roland Hanna, George Mraz, and Billy Hart on drums. .

.

GC When he left Thad Jones’s band in ’77 and went out on his own, it was basically an announcement that he was no longer a big band player, that he was available. He immediately started getting invited to play in clubs overseas and started recording as a leader. He was nominated for three Grammy Awards. He’s on the Grammy Awards telecast playing “My Shining Hour,” appropriately enough. He really went through a renaissance. It was extraordinary. And all these younger musicians wanted to play with him. But cigarettes; cigarettes, man. He just couldn’t get off them.

BH He was a constant chain smoker?

GC Yeah, his entire life, and smoking weed as well. I mean, just constantly smoking, and Camel straights too, no filters.

BH A couple of people noted in your books how remarkable it was, given his overall lack of fitness, you might say, and his chain smoking, that he had the stamina to push all that air through that big horn.

GC It might have kept him alive longer, quite frankly, because it might have worked his lungs and cleared out some of that goop. Hamiet Bluiett, who was a pretty big guy, said that when he heard Pepper play live, he was struck by how much less volume Pepper was producing than he heard on his recordings. He was only five-foot-ten, very, very thin. Small chested. But it’s not about the volume. It was about the overtones. He got all those incredible overtones, so his sound was very rich and powerful.

BH I’d like to have you paint a little more of a picture of Pepper as a human being. You write in your book, “Over and over again, my interviewees affirmed Adams as a complex individual, a hero, a genius, a model of grace, an intellectual, a virtuoso musician and stylist. Yet someone also very hard to calibrate.” Would you share your insights into that?

Courtesy of the Estate of Pepper Adams

Pepper Adams, early 1970s

GC It took me hundreds of interviews to get a composite of Pepper as a fully rounded person. I had to understand the complexities of his personal life, his relationship with his mother, especially his time in the military, many of those things that he wouldn’t discuss with me. Repeatedly, I kept hearing: “He played the baritone like an alto. He was a genius, he was a sweetheart, a wonderful person.” Max Roach said he was one of the most well-liked people in the industry. And it’s obvious why. He was such a kind-hearted, non-judgmental, very sweet man.

…..But the last thing I wanted to do was to write a chronological book, because that is a cliche and Pepper hated cliches. That wouldn’t have been true to him. I wanted to capture all these nuances and give a composite of his character. Sort of an emotional archaeology, as my wife would say, but not be saddled with these trite approaches where I’m mostly writing about his recordings or presenting his life in a cradle-to-grave manner. That stuff is so boring. I really wanted to capture who he was, his humor, even his flaws.

…..I had a chance to be a friend of his and to know him for about two years. I understood the humor, I understood the warmth. I understood his complexities, along with his love of classical music and his devotion to Duke Ellington. I just wanted to flesh all that out. I should also say that as a biographer, there’s a lot of stuff in Pepper’s life that I found gripping because it echoed my life. I was brought up by a single parent, too; I love classical music; I was also a sports fan like he was. I tried to detach myself as much as I could, but there are certain things that struck me. The pressure of being the male in the family as a young adolescent is a difficult thing: I experienced that because my parents got divorced when I was nine. He had to deal with being a breadwinner, going out as a child and selling cigarettes door-to-door to bring in money. Not being able to really have a childhood, in some respects.

…..But the process of writing a biography is a self-discovery for the author, too. It was really a fascinating experience. I was listening to an interview with the filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich speaking with the great French director Jean Renoir. He said, “Jean, when you start a picture, do you know what it’s going to look like?” And Jean said, “Of course not. If I know what the picture will look like, I have no reason to make the picture.” I thought that was a fantastic thing. Because if you’re an author, if you’re a film director, it’s a process of self-discovery. But I always tried to make it true to Pepper, true to what he was all about. That’s why I tried to do it in reverse chronological order in the second half. And I tried to do it thematically throughout the book, kind of terraced in the second half, but I didn’t want to start with, “He was born…” That has no interest for me. I was always trying to be very consistent with what Pepper was like. Whether he would like me discussing his alcoholism or his personal relationships, I don’t know. But I felt that I had to do that as a biographer.

BH Your interviewees describe him as a man of contradictions. You write that they often described him as, “an unworldly-looking sophisticate, a white musician who sounded like a black one. A dynamic, commanding saxophonist who was soft-spoken and mild-mannered off the bandstand.” I was struck by the contrast between how assertive Pepper was musically—I mean, he was just slashing and burning on the bandstand—but apparently had difficulty asserting himself off the bandstand to proactively seek work, to promote himself, or to get the kind of promotional support that he rarely had.

GC Yes, it’s really striking. He would dress like a farmer, but he was one of most sophisticated people I’ve ever met. And he was a white musician who was really, in a sense, adopted by the black musicians as one of them. He told me that he didn’t know how to assert himself, it just wasn’t in him. And I think maybe that comes from his childhood, from a lack of self-esteem.

BH You mentioned his being embraced by the Black musical community. It’s so striking to me. He had some important mentors in his life, and they were all Black musicians. And so many of his closest friends were Black musicians. It’s quite remarkable that he was also the only white guy on any of the Blue Note recordings during the 50s, 60s, and part of the 70s.

GC Right. One of my subjects said that Pepper decided very early on that he was going to be a purist, that he was going to get the music from its source. And that meant from the great Black players, some in Detroit, when he was first coming up. He was close friends with pianist Bobby Timmons, who said Pepper was, “the only white man I ever loved.”

…..He was also a very encyclopedic kind of guy. If he read Anthony Burgess, he was going to read all of Anthony Burgess, or all of William Trevor, or all of Nabokov. That’s the kind of guy he was. When he wasn’t on the bandstand, he was off by himself, smoking cigarettes, or listening to Ellington and reading. And even during intermission at gigs, he wanted to push away fans and women, and just go to a cheaper bar nearby, smoke a cigarette and hang out.

BH I’d love to get your thoughts on his ballad playing, because in addition to all the hard-swinging, hard bop-oriented kind of stuff that he’s so known for, his ballad playing is extraordinary. They’re so expressive.

GC Yes, he was a wonderful ballad player, and very expressive, especially on his own compositions. He explained to me once how he wrote them; that he wanted a bittersweet quality that was a little outside the changes so it would come off in that kind of Strayhorn-esque style. He was obviously very influenced by Billy Strayhorn in that way. I love Pepper’s seven ballads.

BH I found it really interesting to learn of his disdain and bitterness for jazz critics and the quality of jazz writing in the press.

GC Yeah, basically, he thought they were hacks.

BH I love the straightforwardness of his comments about the critics, where he said—and I’m sure this is something that a lot of musicians share—“When I’m praised by a critic, it’s usually for the wrong reason because he thought he heard something whereas in fact, it was something else.”

GC He felt that, as a group, the people who were writing about jazz weren’t what they should be. I think it’s much better now, quite frankly, particularly because musicians, some great musicians, are starting to write about the music. But back then, Pepper was pretty much overlooked.

…..There was one review he told me about, of that date, The Cats, that he was on with John Coltrane. The reviewer wrote about Coltrane as “hysterical and oriental!” Pepper said that every time after that he saw Coltrane, he would remind him about “hysterical and oriental” and Trane would break up completely. He thought art critics were even worse than jazz critics. I went to his place after he passed away, and I looked at his library. He had maybe 200 or 300 art books, all with color illustrations. He just was very involved with art.

BH It was interesting to learn that he and his frequent musical cohort, Donald Byrd, were both seriously into art and that Donald was quite a collector.

GC Yes, and Byrd was onto Romare Bearden and many other black painters very early, and he collected them. I think that Byrd’s estate is valued in the millions and still up for grabs. Byrd had the contract with Blue Note, Pepper was the side man. Byrd could afford to collect. Pepper could only afford to go visit galleries. There’s this one great story about Pepper attending the opening of a new wing at the Detroit Institute of Arts. He was walking around talking about the art with his friends. Some art critic in attendance was a little intimidated, saying, “Who is this guy?” Just walking around giving an exegesis about this scene or this painter: This art critic was just incredulous! Pepper had a brilliant, brilliant mind.

BH In closing, Gary, what are the one or two things you hope readers of your two biographies will learn about Pepper Adams?

GC He was an extraordinary American artist, truly peerless, and a great human being. In my view, that’s quite rare.

BH Well, it certainly is conveyed beautifully in your work. Thanks for this conversation, Gary, I appreciate it.

GC You too, Bob, thanks very much for this.

.

A closing video: Pepper Adams featured with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra in Denmark in 1977, on Jones’s composition, “My Centennial.”

.

.

___

.

.

Gary Carner is the author of two previous books: Jazz Performers: An Annotated Bibliography of Biographical Materials, and The Miles Davis Companion: Four Decades of Commentary.

.

.

___

.

.

The following Spotify playlist contains many examples of Pepper Adams’s playing, as a sideman and a leader.

.

.

.

___

.

.

This interview was hosted by Bob Hecht, who frequently contributes his essays, photographs, interviews, playlists and personal stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. He has a long history of producing and hosting jazz radio programs; his former podcast series, The Joys of Jazz, was the 2019 Silver Medal winner in the New York Festivals Radio Awards. In addition, he is a widely published fine art photographer, whose work has appeared multiple times in The Sun, LensWork, Black & White Magazine, Zyzzyva and other periodicals, as well as in the book, Dream of Venice in Black & White, published by Bella Figuera Publications. He lives with his wife in Portland, Oregon. His photo website is roberthecht.com.

.

.

Bob has conducted several fine interviews for Jerry Jazz Musician. Click here to read “Life in E Flat” – a conversation about Phil Woods – with pianist Bill Charlap and jazz journalist Ted Panken, and click here to read his interview with Alyn Shipton, author of The Gerry Mulligan 1950’s Quartets.

Click here to view all interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here to read “A Collection of Jazz Poetry – Summer, 2023 Edition”

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

WOW gary c , last time we spent together you had just started getting to know Pepper – congrats on the many years of research and success in bringing Pepper’s story – what chops he had on the baritone ! – john king -ps, thanks bob , gary c is an old college buddy