.

.

.

Gone Guy

Jazz’s Unsung Dodo Marmarosa

.

By Michael Zimecki

.

…..This is about a missing person. He went missing many times during his life, periods of brief hiatus from reality, lasting a few minutes to several weeks, that were probably in preparation for the big disappearance, his Vanishing, the not-so-giant sucking sound that was his life.

…..His name was Dodo Marmarosa, and he was a musician. His instrument was the piano, and the music he played was jazz, an art form that also went missing — gone by 1959, according to Nicholas Payton. Sorry, Wynton, but jazz, like Payton said, “ain’t cool” no more—“it’s cold, like necrophilia.”

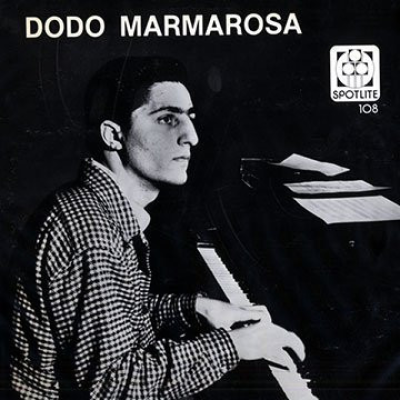

…..Dodo Marmarosa was “cool” before jazz wasn’t. Jazz journalist Leonard Feather honored him with the accolade in 1948, around the time the cool aesthetic was being born. A year earlier, Esquire Magazine gave Dodo a New Star Award; critics predicted he would dominate the jazz scene for the next 30 years.

…..Within a few years, however, he had either fled the scene or it moved on without him. Dodo resurfaced briefly in the early 1960s before vanishing again. In 1992, his obituary appeared in the papers, but Dodo wasn’t dead; he was only missing as he had almost always been.

…..Dodo was born Michael Marmarosa in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1925. He told Uptown Music’s Robert Sunenblick that he got tagged with the “Dodo” moniker as a kid because he couldn’t pronounce his given name. The diminutive sobriquet poked fun at his appearance as well as his verbal skills: Dodo had a large head, an ungainly posture, and a beak-like nose. He resembled an extinct bird.

…..The dodo, Raphus cucullatus, was a flightless bird with a long bill. The etymology of its name is unclear, although some sources indicate that it was derived from the Portuguese word doudo, meaning “crazy” or “fool.” The bird’s inability to fly made it easy prey for sailors, who hunted it for sport. Some controversy surrounds the date of the bird’s extinction, which was not immediately noticed, partly because many doubted that it had ever existed.

…..That, in a nutshell, was Dodo Marmarosa. It sums up his whole life, except perhaps for the flightless part. (More about the sailors later.) Dodo moved around. He went to the West Coast. He recorded in Chicago. He had a gig in Montreal. But his journeys were like a random walk that always brought him back to his starting point, “a slow, gloomy circling back to oblivion, “as Leonard Feather put it, “spelled P-i-t-t-s-b-u-r-g-h.”

…..Dodo was not only born there, but he also grew up there, living in the Larimer section of the city, home to many ethnic Italians. His grandfather hailed from a small town in Campania; his first-generation parents always spoke English in the house. Perhaps that’s why he had difficulty saying his first name: in mellifluous Italian, it’s three syllables, in fellifluous English, only two. Michele (pronounced [miˈkɛːle]) oriented to sounds, not words—to notes, keys, and tones. He took up piano at age nine. He memorized each key on the keyboard and the sound it made when he struck it.

…..Around this time, he went missing for the first time. Playing off the keyboard, he imagined new naturals, flats, and sharps, finishing phrases in his mind. To an outside observer, he looked distant, far away. His parents thought he had zoned out.

…..They arranged for Michael to study piano with a private teacher, a young woman named Evelina Palmieri. The eldest daughter of a shoemaker from Siena, she lived on Larimer Avenue, just around the corner from their home on Paulson. During a time when Italians were still racially suspect, Evelina had gone to college, studying music on a scholarship at Carnegie Tech, where the steel baron’s front-line managers trained. Dark-complected, her photo stood out from the pages of the Whistle, her college yearbook, against the backdrop of her lighter-skinned classmates. Evelina parted her dark hair in the middle and had a smile like Mona Lisa’s. Michael had a crush on her.

…..He tried to impress her by working hard at his craft, practicing virtually around the clock, not pausing to take nourishment – he would eat at the piano with one hand while he kept playing with the other – and barely stopping to sleep, his piano keys substituting for a pillow and his bench cushion for a sheet.

…..Under Evelina’s tutelage, he became a classical music virtuoso. At age 14, he played Chopin’s Scherzo in D-flat at a Young Musicians Concert sponsored by the local Musicians Club, and a career as a classical pianist loomed in his future. Michael might well have gone down that path had he not fallen in love for a second time.

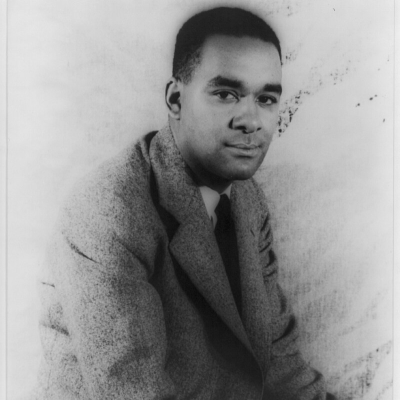

…..His second love was jazz, and the person who inspired it was the Pittsburgh legend Erroll Garner.

William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Erroll Garner, c. 1946-1948

…..Four years older than Marmarosa, Garner started his musical career at the age of 7, playing with Uncle Henry’s Kan-D-Kids under the name of “Gum Drop.” Jazz vocalist and vocalese innovator Edgar “Eddie” Jefferson was also a member of the Kan-D-Kids, appearing as “Jelly Bean”—another gone guy, as in very gone, he was shot to death outside Baker’s Keyboard Lounge in Detroit on May 9, 1979, after performing before an audience that included film star Brenda Vaccaro, girlfriend of alto player and Jefferson sideman Richie Cole.

…..By the time he was in high school, Dodo’s idol, Erroll Garner, was a fixture in local clubs. Marmarosa heard him in one of them and was enamored by the sound; he rushed home and tried to reprise what Garner was doing on the piano. Garner and Marmarosa became friends, jamming together frequently.

…..Another friend, Jimmy Pupa, a trumpeter, got Dodo his first real job, a gig with the Johnny “Scat” Davis band. The band had a talented group of players, including Buddy DeFranco on the clarinet. When the Davis band broke up, Marmarosa, then 17, followed his fellow Italian to the Gene Krupa band.

William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Gene Krupa, 1946

…..The band was playing in San Francisco when Krupa was arrested and charged with drug possession and contributing to the delinquency of a minor. The minor in question wasn’t Dodo Marmarosa; he was a prop boy named John Pateakos, and he got himself and Krupa in trouble after he filched some of the bandleader’s grass and got caught with it. Krupa was sentenced to 90 days in jail on the possession charge and faced an additional 1-to-6 years in San Quentin for corrupting the thieving prop boy’s morals.

…..While Krupa was cooling his heels in county jail on the first charge and awaiting trial on the second, his band kept going under the leadership of Roy Eldridge, a trumpet player, who, like Dodo Marmarosa, heralded from Pittsburgh, where he was born and grew up. Eldridge took the band east, away from trouble, but trouble had a way of finding his young pianist.

.

Dodo and the sailors

…..On June 9, 1943, the band played in the ballroom of The Met, formerly known as the Metropolitan Opera House of Philadelphia. Built in 1908 by impresario Oscar Hammerstein I, grandfather of the famous lyricist, the historic structure is located on Broad and Poplar streets in Francisville, North Philly’s oldest neighborhood. The band played into the night and well into the morning. After their set was over, Dodo and Buddy decided to take the subway downtown, intending to get an early breakfast.

…..A continent away, the “Zoot Suit Riots” were raging on the West Coast. The U.S. War Production Board was regulating civilian clothing; garments that used profligate amounts of fabric were considered wasteful and unpatriotic. A particular target of ire was the zoot suit with its high-waisted baggy pants and shoulders padded “like a lunatic’s cell,” as the zoot-suiting Malcolm X once put it. In San Diego and L.A., mobs of U.S. servicemen, off-duty cops, and civilians ready to brawl were patrolling the downtown streets for zoot-suiting Pachucos and Pachucas. The resulting clashes made headlines across the country.

…..When they boarded their subway at Broad, Dodo and Buddy were still wearing their band uniforms–light blue gabardine jackets, darker trousers, starched white shirts, and bow ties. When they arrived at City Station, they were spotted by several Navy men—some accounts say there were two of them, others as many as five—who mistook the band uniforms for zoot suits. The sailors crossed the tracks and attacked the two musicians.

…..Marmarosa got the worst of it. According to DeFranco, Dodo was dropped headfirst on a railway tie and knocked unconscious. Later, the piano player was taken to Hanneman Hospital, where he lay in a coma for 24 hours and was treated for a possible skull fracture. “Dodo was always a little off,” DeFranco said, “but he seemed different after the beating. . . . I think it created psychological problems for him.”

…..DeFranco was quick to observe that Marmarosa’s head injury didn’t affect his playing. If anything, it got better.

.

Dick Tracy Liquidates 88 Keys

…..No, Chester Gould’s famous flatfoot did not shoot a keyboard. Instead, he ended the career of a piano-playing comic-strip villain named 88 Keyes: the fictional villain lasted exactly 88 days before Tracy cut him down with a machine gun. Keyes was subsequently memorialized by Ralph Burns, himself a pianist and a composer with the Charlie Barnet band, in a jazz composition entitled “Dick Tracy Liquidates 88 Keys.” Burns flubbed the spelling of the Keyes’ name when he copyrighted the song, or perhaps he simply preferred “Keys” to “Keyes.” No matter, Barnet didn’t like the title anyway. So, he renamed it, calling it “The Moose” in honor of the latest addition to his band, the seventeen-year-old Michael Marmarosa.

William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Barnet, 1946

…..Michael joined the Barnet band after Krupa’s folded. “The Moose” was yet another nickname lampooning his ungainly appearance, but it also was an accolade to his solo performance on the Ralph Burns track.

…..“Here, in a trice, modern jazz was born, or at least baptized,” proclaimed jazz historian Gunther Schuller. He praised “The Moose” as a “veritable masterpiece,” presenting the teenage pianist in a bright, new amalgam of nascent bebop and Count-Basie-style minimalism.

…..According to Dieter Saleman and Fabian Grob, authors of a guide to Dodo Marmarosa’s recorded music, the teenager’s solo performance on the Ralph Burns track was perhaps “the first manifestation of bebop piano playing on record.” Without a doubt, it anticipated essential characteristics of a fully developed bebop piano style, a style Marmarosa would master and make famous in the years to come.

.

The Birth of Bop

…..As jazz critic Leonard Feather tells it, bebop sprung, Houdini-like, from the musical straitjacket of Big Band swing with its singsong pattern of simple syncopations, frequent dotted- eight-and-sixteenth notes, and steady four-beats-to-the-bar rhythm. In Inside Be-bop, Feather described the technical features of the new music, like flatted fifths, accented up-beats, and unusual melodic intervals, but bebop essentially was a state of being, one that took the be from its name and turned it into a mode of improvisation and self-expression.

…..Bebop marked a shift of attention from orchestral ensembles playing dance music from ballroom bandstands to soloists playing in a small combo in nightclubs. The shift was conditioned in part by the Selective Training and Service Act, which took tuxedoed musicians and put them in military uniforms, and a wartime cabaret tax on dancehalls that made Big Band music cost-prohibitive. There were other factors, especially sociopolitical ones— a reaction to the cultural appropriation of black music coupled with a desire to make jazz truer to its African-American roots. We will have more to say about this later, particularly as it concerned the white, bebop-piano-playing Dodo Marmarosa, but, for now, suffice it to say that bebop, with its faster tempos and more intricate melodies, was musically more complex than its swing jazz forebearer. With its overarching emphasis on jazz as a form of art, it also required greater inventiveness and musical virtuosity to produce and perform it.

…..The new music’s promise of freedom appealed to the self-conscious but musically talented Dodo Marmarosa, but, both musically and philosophically, bebop was a tripwire act, and its central players often failed to navigate the Sartrean gap between Being and Nothingness.

.

Bird on a Tripwire

…..The paradigm case is Charlie “Yardbird” Parker, whose descent into madness was lubricated by alcohol and further greased by heroin. Ralph Ellison once described Bird as “a man dismembering himself with a dull razor on a spotlighted stage,” but that spectacle was still in the future when Dodo and Bird met.

…..In January 1944, while the Barnet band was playing in New York, Dizzy Gillespie briefly filled in at trumpet, and Diz invited Marmarosa home to jam with him and Parker. The two men had a lot in common—one was named for a flightless bird, the other would soon be in free fall—but Parker was wedded to 52nd Street, the Manhattan center of jazz life enshrined by Thelonious Monk’s bebop anthem, “52nd Street Theme,” and Marmarosa was soon to take up residence on the West Coast, first as a member of Tommy Dorsey’s band, later with Artie Shaw’s Gramercy Five.

…..Circumstances brought them together again. Toward the end of 1945, the Charlie Parker/Dizzy Gillespie Sextet left New York for its first West Coast engagement. They played at Billy Berg’s Club in L.A. to mixed reviews. The engagement ended in February, but desperate to score some heroin, Parker sold his airplane ticket home to obtain the cash to buy some. Stranded in California, without a job or funds to live on, a hole in his arm marking the spot where his money went, Parker was subsequently maneuvered into an exclusive recording contract with Ross Russell’s fledgling label, Dial.

William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress

Charlie Parker, c. 1947

…..The first recording session was scheduled for an overcast day at the end of March. Prior to the session, Parker got into an argument with his pianist, the “legendary” Joe Albany. According to Albany, they were playing at L.A.’s Club Finale with an air shot on a local radio station when Bird started “singing at me like I wasn’t comping right. I did it every which way, and finally, I did what I thought was backward, comping out of time, [which] still didn’t please him, so I turned around and said, ‘F___ you, Bird.” Parker thereupon fired Albany, opening the door for a new sideman on his first Dial session.

…..Dodo Marmarosa seized the opportunity. Fresh from performing a virtuoso piano solo on Artie Shaw’s recording of George Gershwin’s “Summertime,” perhaps the best cover of the famous lullaby ever, he was tapped to replace Albany. The rest is music history. The March 26, 1946 recording session is one of bebop’s finest, featuring “A Night in Tunisia,” “Ornithology,” “Yardbird Suite,” and “Moose the Mooche.” “A Night in Tunisia” was penned by Dizzy Gillespie, who purportedly wrote his first draft of the song on the bottom of a garbage can. The other three tunes were composed by Parker—the titles of two of them, “Ornithology” and “Yardbird Suite,” play on his nickname. All four rank among the landmarks of bebop music. Dodo Marmarosa’s work on the session was instrumental to earning him that New Star award mentioned earlier in this piece. Two other sideman on the session—Miles Davis and Lucky Thompson—also received Esquire Magazine New Star awards.

…..Ironically, Bird was the only member of his Septet who failed to cash in on his contract with Dial. Under a handwritten agreement signed a few days after the March recording session ended, he assigned 50% of his Dial royalties to Emery Byrd, better known by his street name, “Moose the Mooche.” A disabled L.A. shoeshine and jazz record stand owner, Emery was also Bird’s drug connection on the West Coast.

…..A month after the Dial session ended, the jazzman hit the first of the many bottoms he would experience in his brief life. Unable to score heroin after Byrd was arrested for dealing, Parker got mightily drunk on alcohol and set the bed sheets of his L.A. hotel room on fire. He was subsequently found wandering in the lobby, wearing nothing but his socks. The bebop legend was arrested and spent 10 days in jail prior to being committed to the Camarillo State Mental Hospital.

…..Bird and Dodo would record together again after the saxophonist’s release from the hospital, but the March session marked the beginning of the end for both men. For Bird it came more quickly—the jazz tripwire walker would die at age 34 less than a decade later while watching jugglers on TV in the hotel room of his patron, Baroness Pannonica de Koenigwarter—but it was a slower unraveling for Dodo.

…..Some of the strings were starting to pull loose by 1948 for the young jazz pianist. He was already known for his eccentric behavior—he painted the bathtub of his L.A. apartment green to resemble the South Seas and was once observed pushing a small piano off a third-floor balcony just to hear what chord it would sound when it hit the ground. On August 28, 1948, he was arrested at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and LaBrea Avenue on suspicion of drug possession after police observed him walking “irregularly.” Police confiscated the marijuana found in his pocket. Dodo told them he had smoked three bowls full after the grass was given to him by a member of the FBI, a statement determined to be “a pipe dream” by the officers who detained him. According to The Los Angeles Times, he was subsequently booked at Hollywood Jail on a charge of violating the Narcotics Act. The Times did not report on the disposition of the case, but shortly after his arrest, Marmarosa abruptly returned to Pittsburgh. Thus began his slow walk toward oblivion.

.

Crow Jim

…..Marmarosa would later deny that his departure from the jazz world was precipitated by his eccentricities, and he made no mention of his arrest. As he told music historian Ted Gioia, “I just didn’t have the chance to do a lot of records.”

…..According to Donald Clarke, author of The Rise and Fall of Popular Music, Dodo may have been a victim of “Crow Jim.” A ‘60s trope for racial discrimination against white jazz musicians, “Crow Jim” is an inversion of “Jim Crow,” slang for legally enforced racial segregation and a pejorative epithet for African Americans. In the Book of Jazz, Leonard Feather credits jazz critic Barry Ulanov for coining the “Crow Jim” phrase, using it to denote the belief that jazz is more “authentic” when played by black musicians. Whites lacked the feeling, the sensibility to play it, or as Gerald Lyn Early put it in a Spring 2019 article for Daedalus describing the Crow Jim ethos, they were simply “too tight-assed . . . to be really good jazz players.”

…..“Crow Jim” was born as a reaction to the theft of swing music by white bands. Thelonious Monk led the resistance, exhorting black musicians to find a way to say things musically that white men can’t, “to create something they can’t steal because they can’t play it.” Bebop was the response. According to James Lincoln Collier, author of Louis Armstrong: An American Genius, bop was “developed by a new generation of aggressive young blacks, who were not only making a revolution in jazz music but were openly bitter about the position of blacks in America, and scornful of the white society, which they saw as hypocritical, shallow and lifeless.”

…..Not everyone shared enthusiasm for the new jazz. Bop removed sing from swing and rolled up the dance floor, making music for the mind, not the booty-shaking body. Calling it “that modern malice,” Louis Armstrong lamented that bop gave listeners “no tune to remember and no beat to dance to,” but bebop, as Dmitri Tymoczko wrote, “was meant to be difficult and baffling,” to shock the jazz establishment and scare the no-talents off the stage.

…..It was also meant to pay homage to the African tradition. As Berndt Ostendorf observes in “The Afro-American Musical Avant-Garde: Bebop Jazz,” bebop musicians reconstructed the blues in a modern idiom and made a conscious effort to rediscover their roots, “instinctively turning to the West Indies, where there was a stronger African cultural baseline” than in the United States. As Ostendorf notes, “Dizzy Gillespie hired black drummers from the Caribbean, among them Chano Pozo, who knew the ritual drumming of the Afro-Cuban Santeria cult.” Gillespie, in fact, summed up the central tendency of bebop jazz when he said, “Man, that’s my music, that’s my heritage.”·*

…..White musicians weren’t excluded from bebop combos—the list of white boppers includes pianists Joe Albany, Bill Evans, Al Haig, and Dodo Marmarosa, trumpeter Red Rodney, clarinetist Tony Scott, saxophonist Art Pepper, and drummer Stan Levy, among others—but they must have felt some pressure to justify their presence inside the temple of cool jazz.

…..Some white musicians complained bitterly about the strictures of “Crow Jim.” In his autobiography, Straight Time, Art Pepper describes how he wigged out on jazz drummer Lawrence Marable after he observed the drummer sneering at him during a gig. “Man, what’s happening with you?” he asked Marable.

…..Marable retorted, “You know what I think of you? You can’t play. None of you white punks can play”

…..“I couldn’t believe it,” Pepper wrote. “Guys I’d given jobs to, and I find out they’re talking behind my back and, not only that, laughing behind my back while I’m playing in a club!”

…..Unlike Pepper or Al Haig, who loudly bewailed “Crow Jim” as “discriminatory activity in reverse,” Dodo Marmarosa never publicly complained that he was treated differently as a bebop musician because he was white. Perhaps that was because he was reticent to say much about anything: one of bebop’s invisible men, he was typically photographed facing his piano, a faraway look in his eyes, too camera shy to pose for the photographer’s lens directly. (In Aaron Gilbreath’s words, he “always looked as if “the photographer had caught [him] off-guard, and after discovering the lens, could only muster the energy to wait for it to do its business and turn away.”) Or perhaps it was because he understood that short of the cost of sunscreen, as Ian Carey once put it, being white is an advantage in just about every area of one’s life.

…..Dodo had surely heard about that night in Kansas City when jazz great Cab Calloway was beaten by a white cop and was charged with assault by the cop who beat him. Dodo had also witnessed racial discrimination firsthand. He was a member of Artie Shaw’s band when Roy Eldridge was barred from entering a venue where his name appeared on the marquee. After he was finally allowed to join the band, Eldridge played his first set with tears rolling down his cheeks. Pepper and Haig had experienced nothing like that. Dodo also knew that black musicians could not eat at the same restaurants or stay at the same hotels while on tour as their white counterparts. As Charlie Mingus once said, “How can you talk about Crow Jim and look at Mississippi?”

.

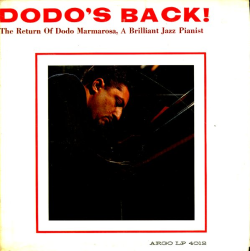

“The Reports of My Death are Greatly Exaggerated”

…..Dodo Marmarosa was on more than 80 records in 1945, but after he returned to Pittsburgh, he recorded virtually nothing until 1962, when he released, to little fanfare, a comeback LP with the title “Dodo’s Back!” In the interim, he married, fathered two children, and divorced, his marriage lasting only a couple of years. His ex quickly remarried, and Dodo agreed to have his daughters take their stepfather’s name in exchange for being released from future child support obligations. The loss of his family must have been a crushing blow.

…..In 1954, Dodo was drafted into the Army, but his tenure as a soldier was even briefer than his marriage. After three months in the Army, he was drummed out on a psych discharge, returning home to spend several more months in a veteran’s hospital, where he underwent electroconvulsive therapy.

…..The practice of applying electricity to people’s heads to cure them of mental problems originated with two Italian scientists, Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini, who treated a man with electroshock after he was found delusional in a railway station. Although its use is generally considered safe and effective today, electroconvulsive therapy has been stigmatized, thanks in no small part to Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Kesey had worked in a mental hospital in the early 1950s when electroshock was often given without muscle relaxants, inducing a seizure that resulted in a full-scale convulsion.

…..After his release from the hospital, Dodo Marmarosa withdrew from the national music scene and faded from public view. He resurfaced briefly in the early 1960s, reuniting with the newly resurrected Johnny “Scat” Davis band in Chicago and serving as an accompanist with the singer, Johnny Janis, on a few audition dubs. Chicago promoter Joe Segal tried to arrange a recording date with the Argo Jazz label, but the vanishing piano man vanished again, absconding on what he later described as “a groovy Mexican vacation.”**

…..In the early 1970s, Dodo Marmarosa performed on and off as a solo pianist, primarily at the Colony Restaurant in Pittsburgh, before his physical health—he was diabetic and had developed a tremor in his right hand—and his increasing mental instability forced him into permanent retirement. Among jazz aficionados, he was widely rumored to be dead—a jazz publication even listed him as deceased—before author Bob Dietsche brought him back from the grave like Lazarus, publishing a piece about him in Oregon Focus in November 1990.

…..Although reports of his death had been exaggerated, “even Dodo sometimes had his doubts,” as Dietsche wryly stated in his piece. “It seems like a reasonable presumption,” he wrote. “[Dodo] hadn’t had a piano job in more than a decade, hadn’t made a record since 1962, and most of the people who remember playing with [him] hadn’t seen him in more than 40 years.”

…..For Dodo Marmarosa, music was more than a vocation; it was his calling, and it remained so throughout his life; even as he drifted away from the jazz scene, he was never far from a keyboard. On September 17, 2002, Dodo entertained fellow veterans by playing music from an organ console at the VA medical center where he was hospitalized. After the performance, his very last, he retired to his room and suffered a fatal heart attack.

…..After his death, it was as if he had never existed. You won’t find his name in the DownBeat Hall of Fame. Jazz pianist Joe Albany got featured in a biopic, but not Dodo Marmarosa. He isn’t even remembered much in Pittsburgh, where he went to die.

…..Leonard Feather opined that Dodo Marmarosa was “probably the most gifted technically, as well as the most versatile of bebop players.” The jazz pianist’s former boss, Artie Shaw, once remarked that he “had an utter purity about him.” But the last word on Dodo’s life and career belongs to jazz producer Ross Russell, whose remembrance of Dodo from the early 1940s when the gifted pianist was in his prime, provides a fitting epitaph. As Russell recalled in the liner notes for “Dodo’s Dance,” an LP on Spotlite,

Dodo was a born dreamer, a man enslaved in a world of sound. Every sound had a secret meaning for him. Certain sounds issued imperious orders. If he was walking down the street and a cathedral began chiming vespers, he would stop, rooted to the spot until the sounds stopped and he was released from their spell. One of his favorite things to do was to stay up all night so he could stand barefoot in the dewy plot in front of [his] house listening to the cries of birds as they awakened to the California dawn.

…..The dusk has finally set. Dodo Marmarosa, that pure soul, that Vanishing Piano Man, is gone for good now, but he should not be forgotten.

.

* As Ralph Ellison once acknowledged, “Jazz is African-American in origin, but it’s more American than some folks want to admit.” One could argue, states Richard M. Sudhalter in Lost Chords: White Musicians and their Contributions to Jazz, 1915-1945 that” the roots of jazz are just as much in marching band music, American musical theater, American vaudeville music, and Jewish Klezmer music as they are in African-American culture.” As Wynton Marsalis put it, “Jazz symbolically is a unifier, the result of hybridization of cultures.”

**The recording session took place some six months later with Marmarosa on the piano, Richard Evans on bass, and Marshall Thomas on drums, resulting in a full LP of unissued material.

.

.

___

.

.

Michael Zimecki is a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based author whose work has appeared in Another Chicago Magazine, Cleaver Magazine, Harper’s Magazine, and The National Law Journal, among other publications.

.

.

Listen to Dodo Marmarosa play piano on “The Moose,” with Charlie Barnet and His Orchestra [Universal Music Group]

.

.

Listen to the 1946 recording of Charlie Parker play “Ornithology,” with Dodo Marmarosa on piano

.

.

Click here to listen to Dodo Marmarosa play “I Thought About You,” from his 1961 album Dodo’s Back

.

.

___

.

.

Click here for information about how to submit your work

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here to read “A Collection of Jazz Poetry – Spring/Summer, 2024 Edition”

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.