.

.

.

Eric Dolphy was perhaps jazz music’s first true multi-instrumentalist, and a pioneer of avant-garde technique. His life cut short in 1964 at the age of 36, his brilliant career touched fellow musical artists, critics, and fans of jazz music through his innovative work as a composer and bandleader, and performing with the likes of Chico Hamilton, Gerald Wilson, Gunther Schuller, Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, and John Coltrane.

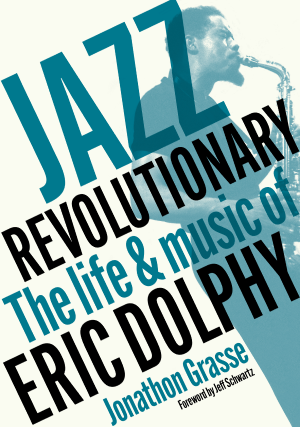

In his book Jazz Revolutionary: The Life & Music of Eric Dolphy – the first full biography of him – Jonathon Grasse examines Dolphy’s friendships and family life, and his timeless musical achievements.

I will soon be publishing an interview with Jonathon about this outstanding book on Dolphy, who was not only a groundbreaking artist, but a man who is also widely remembered by those who knew him as a kind and gracious human being. Meanwhile, he has generously consented to allow readers of Jerry Jazz Musician the opportunity to read the book’s introduction, which I present here.

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

Jazz Revolutionary: The Life & Music of Eric Dolphy

Introduction

.

…..This book chronicles the life of jazz musician Eric Dolphy, recounting the artistic range and creative depth of his work as a multi-instrumentalist, composer, and bandleader. The Los Angeles native and American original collaborated with some of the biggest names of the early 1960s avant-garde. A leader on seven albums released during the last four years of his tragically short life and several more posthumously, his innovative sound also appears on a remarkable number of recordings as a sideman. Dolphy famously worked with the John Coltrane Quintet, Charles Mingus’s Workshop and Sextet, and Ornette Coleman on his seminal album Free Jazz, recorded in 1960. The stylistic paths of these musical giants led from the hard-bop successes of the 1950s toward a diverse broadening of styles and an expanse of vital cultural references characterizing the early 1960s. Dolphy helped pioneer post-bop’s frontier with free jazz, though he regularly plied the tonal waters of standard tunes and brandished a license to play as he liked, in a style all his own, spicing up even ordinary sessions with floridly chromatic, expressive solos. His musical poetry spoke of what was possible.

…..The only child of Afro-Latin immigrants, Eric came of age in mid-century segregated Los Angeles immersed in adolescent dreams of performing classical music before awakening to swing jazz and ‘race music’ styles soon relabeled R&B. As a teenager, he consumed bebop, experienced the WWII-era jazz culture of Central Avenue clubs, and embraced a studious life of music. His multi-instrumentalism emerged from artistic curiosity and youthful plans of augmenting a career in modern jazz by becoming a professional musician, perhaps even a studio session player for film, radio, and television, though during a time when non-whites were very rarely considered for such positions. After serving three years stateside in the US Army during the Korean War, he returned to a rapidly changing Los Angeles, Central Avenue’s bright lights fading as his early career blossomed. Dolphy participated in rock’n’roll recording sessions, cutting-edge club dates, and innovative after-hours jams of an experimental nature. There he met and played with Mingus, Ornette, and Coltrane, and counted Southern California jazz legends Gerald Wilson and Buddy Collette among his closest friends and musical mentors.

…..At twenty-nine, Dolphy joined the Chico Hamilton Quintet with its nationwide touring schedule of club dates, festivals, and recording sessions, landing in New York a mature player in late 1959. He emerged on the East Coast from the West Coast’s shifting tides of cool jazz and experimentation as a late bloomer, recording his first album as leader, Outward Bound (Prestige, 1960). His star shined for the next four and half years, until his death from undiagnosed diabetes barely two months after relocating to Paris to start a new chapter and to marry his fiancé, American dancer Joyce Mordecai. He left the USA for Europe to make a career playing his own music and never came back, a sad and shocking end to a short life full of promise. Accompanying his recordings and compositions, the Dolphy legacy includes a deep and positive impact upon many friends and colleagues who uniformly recall a quiet, giving individual offering support and gratitude; one who smoked and drank socially while avoiding the pitfalls of substance abuse, alcoholism, and heroin addiction that plagued some of his closest friends in the music community. In contrast to his kind, low-key offstage personality, this introspective musician was, onstage and in the recording studio, a fiery preacher, a sublime magician, and a renegade fugitive all rolled into one rebellious artist playing three instruments.

…..Jazz historian Ted Gioia summarized the 1950s West Coast jazz scene by stating that ‘no other place in the jazz world was as open to experimentation, to challenges to the conventional wisdom in improvised music, as was California during the late 1940s and the 1950s,’ spotlighting ‘The Chico Hamilton Quintet’s swinging chamber jazz to Ornette Coleman, and big-band writing as diverse as Roy Porter’s bop band, Gerald Wilson’s harmonically rich and Latin-influenced charts.’ Dolphy was deeply involved with all four of these iconic artists: an essential voice in one of Hamilton’s best groups, he jammed with Ornette in 1954–55, was an original member of Porter’s 17 Beboppers, and became one of Gerald Wilson’s closest friends and musical associates. ‘It is the enormous diversity of the music, the ceaseless churning search for the different and new,’ Gioia continues. ‘It is this characteristic that unites a Stan Kenton and an Ornette Coleman, a Charles Mingus and a Jimmy Giuffre, a Shelly Manne and an Eric Dolphy.’ Jazz scholar George E. Lewis also places Dolphy squarely within the late 1950s avant-garde Los Angeles, brimming as it was with radical approaches to improvisation and experimental sensibilities, partly transplanted to New York’s expanding vortex of progressive jazz. There, he and his close friend and musical partner John Coltrane influenced each other as they broadened their solos in live performances together beginning in 1961, launching extended journeys of epic durations into the unknown. Dolphy engaged Mingus’s embrace of the radically new in his suite-like works, in studio recordings, and in monumental excursions captured live, a major driver in jazz’s push forward from cool and hard bop into post-bop and the uncharted territory of free improvisation.

…..Jazz Revolutionary approaches the artist’s recordings as essential cultural artifacts, as primary texts. Beyond live performances, first-issue vinyl albums and reissues in the years and decades following his passing were the principal means by which his music was shared and appreciated. These recordings are here identified chronologically and placed within the context of his development and collaborations, balancing descriptive narrative and accounts of artistic growth with select discographic detail in footnotes. Live performances including bootlegged radio and television broadcasts and illicit club recordings trickled out over the decades, vital live concert recordings of Dolphy’s groups, the Coltrane quintet, and outfits led by Mingus offering some of his most stunning solos.

…..Impulse’s 1997 release Coltrane: The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings from November 1961 offers revelatory examples of Dolphy’s playing, far outshining what listeners originally heard of him from those dates on Coltrane Live At The Village Vanguard (1962) and Impressions (1963). Over a half-century following its recording, Musical Prophet: The Expanded 1963 New York Studio Sessions (Resonance Records, 2018) provided the complete set of FM Record’s substantial July 1963 sessions resulting in the albums Conversations (1963) and Iron Man (Douglas International, 1968). In July 2023, Impulse! released the double-LP album Evenings At The Village Gate: John Coltrane With Eric Dolphy, capturing the quintet’s first club appearances. Many albums enlist his sideman skills—a job for which he never failed to give his all—and there exists a broad range of such supportive work, from that of a featured guest voice lending a major improvised sound as soloist to that of a background or secondary player reading parts. Jazz Revolutionary examines the full scope of this recorded work and focuses on his most important achievements.

…..Dolphy’s musical vocabulary was imbued with the phrasing and contours of human speech, bird calls, animal sounds, and timbral excursions employing extended techniques. Dolphy used microtonal inflections and multiphonics resulting from special fingering and embouchure methods. To his mastery of post-bebop technique he added unconventional yet disciplined sonic worlds, making room for extreme melodic leaps, non-pitch-related phenomena, and unusual sounds. His solos frequently make use of uncommon formal schemes employing unique gestural repetition, groupings of free-ranging melodic figures and multi-directional statements, and sound shapes demanding fresh interpretation. He could wrestle a solo away from a tune’s confines, foregrounding compositional notions of improvisational freedom. His reimagining of the solo’s role in the jazz tune often avoided routine form, conventional phrasing, and development based solely on harmonic progressions and thematic variations. Yet, while arguably striving to defeat audience expectations, Eric always said that his playing and hearing followed the harmony, speaking of his solos in terms of chordal tones and scale degrees. His music contains sophisticated reflections of Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Sonny Rollins, as well as the blues, and honking R&B—a playful, sometimes humorous vision at once futuristic and primitive, space-age puzzles draped in an African American–derived spiritual past, championing the human voice, sounds of nature, and modern jazz aesthetics. The octave displacement found in Baroque-era compound melody, and wedge-like alternations of moving lines against reiterated pedal points, are here achieved masterfully on three instruments in the atomic age of Dolphy’s shamanistic Iron Man.

…..Hard-driving numbers such as ‘G.W.,’ ‘Les,’ ‘Miss Ann,’ and other original compositions such as the blues-noir classic ‘245’ and ‘Serene,’ from his first albums as a leader, remained on his set lists until his passing. He recorded compelling duets with bassists on each of his instruments, creating absorbing, chamber-music-like pieces often transcending jazz. Flutist, composer, and Dolphy scholar James Newton writes, ‘Eric was developing multiple styles of music simultaneously. . . . There was this highly chromatic post-bop; then music that combined elements of jazz and contemporary classical; and jazz combined with world music.’

…..As Eric’s virtuosic musical prowess earned praise from progressive jazz audiences eager for the ‘new thing’, his skills and interests also gained entry into the third stream crossover world combining jazz with contemporary concert music. With composer and conductor Gunther Schuller, his closest supporter and collaborator in this milieu, Dolphy engaged in third stream modernist conflations of jazz and twentieth-century concert music of European descent, broadening his celebration of creative freedom.

…..Jazz Revolutionary also examines this innovative musician’s critical reception, both good and bad, to illustrate his world as seen through the pages of, among other periodicals, DownBeat magazine. Championed by a circle of collaborators, connoisseurs, and those with an ear for innovative playing, Dolphy also faced stiff resistance from high-profile music journalists, critics, venue owners, and fellow jazz musicians. Today, some of that negative criticism appears painfully dated, proof of his status as a cultural subversive bridging polarized aesthetic camps within a moving musical landscape. This book balances an understanding of Dolphy’s charisma of aesthetic deviance and cultural Blackness with the value and nature of his artistic genius while considering a surrounding world of change. Framed by a clear timeline of events and developments, the ebb and flow of this book stays close to Dolphy’s development as an artist, his recording sessions, performances, and collaborations, its pace slowing to reflect on his influences, evolution, and accomplishments, quickening to catch up with that changing world.

…..Jazz has always been defined by the eloquence and power of collective expression and individual improvisation. In Dolphy’s uncompromising solos on alto saxophone, flute, and bass clarinet, and in his dynamic original compositions, audiences heard a revolutionary voice that helped launch a new era of expressive freedom in jazz. He forged a unique style within an emerging climate of post-bop, experimentalism, and free jazz, at a time when African Americans were engaged in intense political struggles for freedom and equality. These vitally important Black Americans were his contemporaries: Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. Dolphy died less than two years before Stokely Carmichael’s introduction of the ‘Black Power’ slogan, yet it is clear to many that his music channels a similar vein of dissent and liberation challenging America’s deep stain of inequality. Those political battles for change were only the beginning, and this harrowing era of violence, and protest in the United States historically weaves into the global crossroads of the Cold War and postcolonial liberation within parts of the so-called developing world, including African nations finding their independence. This current of Black pride and Pan-Africanism empowered anew some corners of the jazz world.

…..Dolphy appeared on the emerging radicalized stage of the Civil Rights Movement’s push against the injustices of racism and racial segregation, and his revolutionary voice speaks to a self-awareness perhaps best described by James Newton:

Eric understood so well that an artist has a responsibility to the past and the future. His studies led him as far back as the timeless beauty of the music of the African Pygmy. (Sometimes I wonder if his constant use of octave displacement didn’t come from the register modulations of vocal pygmy music.) In his music one can hear the crying, moaning, and wailing that has characterized the hopes and dreams of the first Afro-Americans who came not through Ellis Island, but through the stench of the bottom of a slave ship. In his music, one can hear a vocal quality that can be traced back to the tonal qualities and nuances of the Western African languages and transferred through the tributaries of gospel music and blues.

Transcending polite jazz entertainment’s traditional roles, he moved toward a new musical kingdom of artistic creativity, conflating notions of socio-political justice, independence, and musical individuality.

…..Freedom obviously encompasses areas vaster than music, and as Albert Ayler said in the context of surviving a harsh, inner-city Cleveland upbringing, ‘I’ve lived more than I can express in bop terms.’ These words are no less true for Dolphy, whose life experience and universalist aesthetic that embraced bird song, Indian music, and Stravinsky, comprised a warrior-monk dedication to exploring diverse musical resources beyond what the extant jazz vocabulary provided. His sound proved a catalyst for other musicians, a contemporary voice of both revolution and reconciliation.

.

© 2024 Jonathon Grasse. Extracted from Jazz Revolutionary: The Life & Music Of Eric Dolphy, published by Jawbone Press (www.jawbonepress.com).

.

.

___

.

.

Jonathon Grasse is a professor of music at California State University, Dominguez Hills, where he teaches world music, music theory, and composition. His work Hearing Brazil: Music and Histories in Minas Gerais is the definitive English language study on that region’s musical traditions, a book complimented by The Corner Club, in which he examines the 1972 album Clube de Esquina by Milton Nascimento and Lo Borges. His articles have appeared in Popular Music and the Yale Journal of Music and Religion, among other publications. He lives with his wife Nanci in Los Angeles.

.

.

Listen to the 1960 recording of Eric Dolphy performing his and Charles Mingus’ composition “Out There,” with Ron Carter (cello); George Duvivier (bass); and Roy Haynes (drums). [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

.

Click here to read other book excerpts published on Jerry Jazz Musician

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

.

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.