.

.

.

The pianist and composer Cecil Taylor’s music could be described as “difficult beauty.” Whether playing a 60-minute solo or a short piece by a large ensemble, his work – which some would say is the ultimate in “free jazz” – stretched listener’s personal boundaries, challenging us to find relevance in his thunderous yet elegant imagination while also being thoroughly fascinated by his unique and obvious genius.

The bassist William Parker – who collaborated with Taylor for more than a decade – said that Cecil Taylor’s life “was a string of mysteries that made a beautiful necklace of precious sounds, dances, and poetry he called music.” That music was an entirely new musical language – and instantly recognizable. And, beyond what was seen on stage, part of Taylor’s genius was evident in his ability to teach that complex and difficultly beautiful language to members of his ensembles.

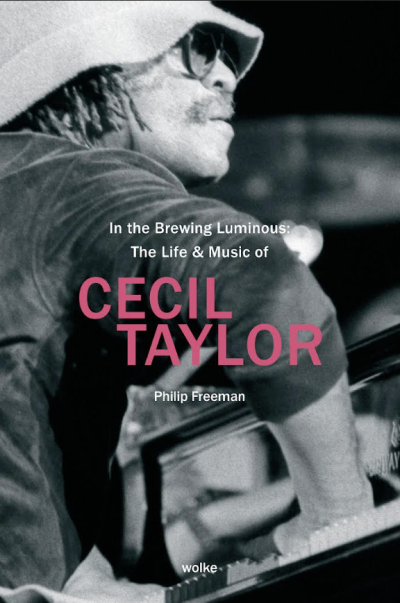

In anticipation of my soon-to-be-published interview with Philip Freeman, who authored the first full-length biography of Cecil Taylor, In the Brewing Luminous, the following is the book’s introduction. Many thanks to the author for providing this opportunity to readers of Jerry Jazz Musician.

.

Joe Maita

Editor/Publisher

.

.

___

.

.

In the Brewing Luminous: The Life and Music of Cecil Taylor

by Philip Freeman

.

INTRODUCTION

…..I met Cecil Taylor at the Whitney Museum in February 2016. I had been invited to interview him for the UK magazine The Wire on the occasion of a retrospective of his life and work, Open Plan: Cecil Taylor, which ran from February 26 to April 24 of that year. The show, partly an exhibition and partly a series of events, included performances by some of Taylor’s former collaborators, readings and lectures, screenings of videos, and displays of album art, concert posters, and other visual ephemera. Taylor himself played three times toward the end of the run, twice on April 14 and once on April 23, with three unique ensembles that included old and new partners: saxophonists Harri Sjöström, Bobby Zankel and Elliott Levin; cellists Tristan Honsinger and Okkyung Lee; bassist Albey Balgochian; drummers Jackson Krall and Tony Oxley, the latter playing electronics; and dancer Min Tanaka.

…..I spent a total of ten or twelve hours, probably, in Taylor’s company over the course of two days. In addition to a formal “interview,” we ate and drank together, hung around outside while he smoked American Spirit cigarettes, and generally enjoyed each other’s company. On the second day, we were joined by a pair of mutual friends: poet Steve Dalachinsky and his wife, poet and visual artist Yuko Otomo. When I left for the last time, he signed my copy of one of his CDs, The Willisau Concert, and I presented him with a gift: Rihanna’s Anti, which had been released a week or two earlier.

….. Before Taylor arrived on the first day, Jay Sanders, the curator who had arranged the whole thing, walked me through the space where the exhibition would be held. Museum staff were still crating up massive, colorful, oddly shaped paintings from a Frank Stella retrospective I had attended with my wife. He explained that the interior walls would be removed to create a giant loft-like space anchored by a Bösendorfer Imperial piano placed by the massive windows that offered a view of the West Side Highway and the Hudson River.

….. We descended to the museum’s lobby to greet Taylor when he arrived in early afternoon, chauffeured from his home in Brooklyn by his personal assistant. He seemed very short, dressed in a multicolored sweater, a heavy coat, and a bright green wool cap, and he moved slowly, due to arthritis in his hip. “I was a dancer. My mother was a dancer. I’ve gotta walk with a cane now,” he grumbled to me.

….. He gazed up at me in a manner at once philosophical and courtly as we shook hands, appraising me with wide, Yoda-like eyes that observed everything with a laser’s focus. We shared an elevator to the eighth floor, and had tea in the room where we would be spending most of our time.

….. Sanders left, and after a few minutes of friendly conversation, Taylor announced, “Now the boring part begins,” and leapt up, suddenly vigorous. He sat at the Yamaha baby grand piano set up by the Whitney’s large picture windows. I was alone in a room with Cecil Taylor and a piano. My heart jumped.

….. I sat at a conference table, facing the windows, and watched as Taylor contemplated the keyboard. Surprisingly, he barely touched the keys. After running through a few warm-up finger exercises, he stopped and stared at the instrument. Every few minutes, he’d strike a note or two, write something down on a piece of paper, and then return to contemplation.

….. He was thus occupied for nearly three hours, as I watched in silence, my attention occasionally captured by flocks of seagulls hovering and whirling around the buildings across the street. It turned out later that Taylor was watching them, too. “The birds that congregate on the top of these buildings here,” he said to me the next day, “the seagulls, man, it’s incredible. This afternoon at a certain point, about thirty of them just came off the top of that building. It was marvelous.”

….. When he left briefly, I crossed the room to glance at his notes; they looked like some sort of linguistic study, stacks of letters rising and falling in pyramidal patterns. A typical sequence might run AFGD/AFGD/CF#, the letters written on a sloping diagonal down the page, with a second set below them. Another sheet, to the left of the first, contained a poem full of references to evanescence and things coming unbidden. When I told him that the “score” reminded me of a Cy Twombly painting, he whispered, “Oh, that’s nice.”

….. After a late lunch in the Whitney’s cafeteria, Taylor and I returned to the conference room and talked for close to two hours about a broad range of subjects, from his philosophy of music, which could consist of as little as a single note, to his family history and his time living in Berlin in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

….. For decades, journalists found the experience of interviewing Taylor simultaneously a thrill and an exercise in futility. In his 2008 book Miles Ornette Cecil: Jazz Beyond Jazz, Howard Mandel wrote, “I’ve met Cecil Taylor but can’t say I know him…I’ve only fleetingly encountered the person behind the performer.” When Hank Shteamer profiled Taylor for Time Out New York, also in 2008, he blogged about his encounter with the pianist, saying, “I wouldn’t classify it as an interview at all, more as a monologue, or even a performance that I was witness to…I was there, in his presence, but I ceased to become a factor.”

….. My experience was somewhat similar, though we did have some focused and vital exchanges, particularly when I was able to provoke Taylor into a response by saying things with which he sharply disagreed. (I wasn’t baiting him; I meant everything I said, which made our conversation all the more fascinating.)

….. There are interviews with Taylor from the 1960s, ’70s and even ’80s that open a window into his artistic process. After a certain point, though, he seems to have decided to approach encounters with writers as a raconteur, drinking and smoking endlessly and ignoring questions, preferring to tell stories from the beginning of his career and share sometimes decades-old gossip about musicians he knew. Occasionally, one of these anecdotes would prove to be revealing of some broader point about art or creativity, but just as often it would turn out just to be a story that amused him, and he would cackle darkly like a boy telling tales out of school.

….. In many ways, evasiveness — or, more accurately, hiding behind a persona crafted as carefully as one of his compositions — was a signal condition of Taylor’s life. He treated every moment of his time onstage as part of the performance, famously telling Mandel in a 1984 Washington Post interview, “you don’t simply walk to the piano.” Indeed, his concerts often began with him reciting his dense, highly abstract poetry from backstage. Eventually, he would emerge into view, clad in the loose, soft clothing of a dancer, and would swirl around the stage with sweeping gestures in accordance with a rhythm no one else could hear, occasionally freezing in place in a dramatic posture. It might be several minutes before he actually sat down at his primary instrument.

….. Similarly, he often seemed to treat being “Cecil Taylor” as a performance. Only about 5’6” even before age shrank him further, he was a light-skinned Black man who dressed with great flair, favoring bright colors, the aforementioned soft, loose fabrics, sunglasses of varying degrees of opaqueness, rings, and a range of hats from baseball caps to knit beanies. He knew how to make himself the center of attention, and did so whenever possible.

….. This public persona, of a man entertaining himself and whoever might be assembled at the time while providing relatively little insight into his creative motivations, never mind the details of his actual art, was somewhat similar to the version of himself that saxophonist Ornette Coleman — a friend of Taylor’s for decades — presented to the press, and thereby the world. I interviewed Coleman twice, and we had two extremely pleasant conversations filled with aphoristic statements and insights into existence, but it was more like talking to a Zen philosopher than a musician. Some years later, after his death, I interviewed several former members of his band, and was told that Coleman would happily discuss the structures and compositional principles behind his work with them at length, but when speaking to journalists, he always reverted to philosopher mode. It was the mask he chose to wear.

….. So, you may be asking yourself — as I have asked myself — why should any writer peer behind Cecil Taylor’s mask? Why attempt to learn the “truth” about a man who made it clear, over the course of a career spanning almost six decades, that what was of primary importance to him was not his life, but his art? As a young and not-so-young man — into his thirties — Cecil Taylor took jobs that were far beneath him, working in a bank, as a record store clerk, as a deliveryman, and as a dishwasher in order to devote himself to the development and refinement of his art. As a mature artist, recognized by the establishment (among other honors, he received a Guggenheim fellowship in 1973, a MacArthur Fellowship in 1991, and the Kyoto Prize in 2013), he maintained a rigorous discipline, practicing the piano for hours each day in his Brooklyn brownstone. Of course, he had a vibrant social life as well. He was often in the audience when musicians he admired performed in New York, and he spent his nights in bars and after-hours clubs. But there was always much that Taylor kept to himself.

….. For that reason, this book will not be a rigorous investigation of the quotidian details of Cecil Taylor’s life. It does not matter where exactly he lived from year to year, where he worked before his art became financially sustainable, what kind of fees he received for his records or his performances, or who his romantic partners might have been. When a piece of biographical information has some bearing on his art — and there are many such connections — it will be discussed. But this is a book about one of the 20th century’s greatest creative minds, a man who unshackled his own music from all external limitations and in so doing inspired generations of other musicians to pursue their own paths. There is more than enough to learn from the work alone.

….. And the work, too, is often misunderstood. There is a romance to the idea of improvised music — florid brilliance flowing in the moment from the fingers and lips of Black instrumentalists — that often causes listeners and critics to lapse, unwittingly and perhaps with the best of intentions, into racist stereotypes. Cecil Taylor’s music, particularly when experienced live, swept over the audience like a tidal wave, coming too fast to be absorbed, and thereby created the illusion that it was arriving ex nihilo. It is only thanks to recordings, which we can listen to over and over until patterns reveal themselves, that his music is as clear and comprehensible as it is.

….. Taylor encouraged this misunderstanding, choosing to rhetorically blur the lines between composition and spontaneous creation partly to throw people off his trail and partly because he — and he’s far from alone among jazz musicians in this regard — believed the distinction was pointless if not harmful. He spoke disparagingly of the mental contortions required to translate notes on staff paper into sounds, claiming that the process sapped the immediacy and emotional power of the performance. He chose not to write his compositions out in standard notation, instead stacking the names of notes on the page in the manner I described above and teaching the music to his bandmates by reciting these strings of letters to them, or playing a figure on the piano and having them work it and rework it through hours of intense rehearsal until it became part of them. But make no mistake, Cecil Taylor — who poet and critic Fred Moten described as “[Duke] Ellington’s most radically devoted follower” — was a composer.

….. As I say, recordings tell the tale. Aside from the fact that he had a very personal and recognizable style, not just of playing but of constructing melodies, there are numerous examples of Taylor and his bandmates re-using specific phrases in various contexts. If one listens to multiple recordings from the 1969 tour of Europe, for example, one can hear Taylor, as well as saxophonists Jimmy Lyons and Sam Rivers, playing riffs and fanfares as frameworks for improvisation. The music of the 1978 sextet is tightly orchestrated, approaching the precision of a chamber ensemble at times. The eleven-member Orchestra of Two Continents made both a studio and a live album in 1984, and the music from the studio album can be heard being re-interpreted in concert. Even in solo performance, Taylor repurposed melodies, often working with a particular piece of material for a few years before setting it aside.

….. His work developed, year upon year, decade upon decade. His earliest recordings are deeply indebted to the players he idolized — Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Horace Silver and others — while pointing down the path he would follow in the years to come. The live recordings from his extended residency in Scandinavia in 1962 exhibit great freedom, but they were immediately preceded by some of his most precisely orchestrated material, and his mid-’60s Blue Note albums (and Student Studies, recorded in Paris) are just as tightly arranged and rehearsed. Taylor’s recordings from the ’70s are very different from his work in the ’80s and the ’90s, and while some of the most interesting music he made in the 21st century exists only in memory (there are recordings, but no plans to release them), trust that it too was very different from what came before.

….. The story of Cecil Taylor is one of resistance, of abandoning an easy path in favor of a more personally satisfying one. And it’s not over; as of this writing, his legacy is very much in flux. But when the dust settles, he will be remembered as one of America’s greatest artists. I hope that this book helps make that case. If nothing else, it exists as a testimony to a composer and performer whose music has brought me joy for more than 25 years.

.

© 2024 Philip Freeman/Burning Ambulance. Excerpted from In the Brewing Luminous: The Life & Music of Cecil Taylor, published by Wolke Verlag (https://www.wolke-

.

.

___

.

.

photo I.A. Freeman

Philip Freeman is a veteran music journalist and the author of New York Is Now!: The New Wave Of Free Jazz; Running The Voodoo Down: The Electric Music Of Miles Davis, and Ugly Beauty: Jazz In The 21st Century. He lives in Montana.

.

.

Listen to the 1966 recording of Cecil Taylor performing his composition “Enter Evening,” with Jimmy Lyons (alto saxophone); Ken McIntyre (alto saxophone, oboe, bass clarinet); Henry Grimes (double bass); Alan Silva (double bass); and Andrew Cyrille (drums). [Universal Music Group]

.

.

___

.

.

.

Click here to read other book excerpts published on Jerry Jazz Musician

.

Click here to subscribe to the Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter (it’s free)

Click here to help support the continuing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

.

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.