.

.

.

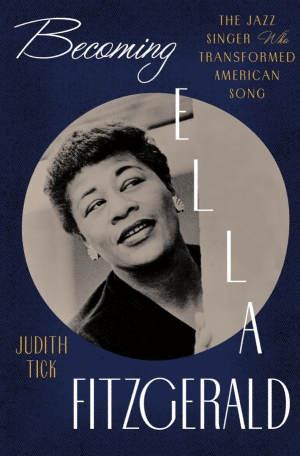

In this excerpt from the Introduction to her book Becoming Ella: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song, Judith Tick writes about highlights of Ella’s career, and how the significance of her Song Book recordings is an example of her “becoming” Ella.

.

(Click here to read our interview with Ms. Tick)

.

.

Excerpted from Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song by Judith Tick. Copyright © 2024 by Judith Tick. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

.

.

___

.

.

…..My fond girlhood memories of Ella Fitzgerald would inspire a more personal—and decidedly ambitious—pursuit in 2010, when I read an interview with Fitzgerald in which she explained how those Song Books I used to listen to—recorded two decades into what was already a thriving career—had marked a significant transformation in her artistry.

…..In the Fifties I started singing with a different kind of style . . . picking out songwriters and singing their songs. Cole Porter was the first. It was like beginning all over again. People who never heard me suddenly heard songs which surprised them because they didn’t think I could sing them. People always figure you could only do one thing. It was like another education.

…..Those consequential Song Books represented a before-and-after demarcation in the long and colorful arc of Ella Fitzgerald’s career. They suggested the ideas of “becoming” and “transformation” as potential themes for a book. For twenty years or so before they were recorded (roughly from 1935 to 1955), Fitzgerald had established herself as a quintessential jazz singer.

…..She had started out as an impoverished young girl from Yonkers, who would later describe her boots as camouflage for her skinny legs. She achieved recognition through an amateur night contest at the Apollo Theatre at age seventeen and then in February 1935 got a real job through a week-long engagement at the Harlem Opera House. After being signed by Chick Webb, who initially said, “I don’t want no girl singer,” she began to transform the role of “girl singer” into a position of leadership. Her success at the microphone transformed not only her career but also the status of other female vocalists throughout the music business.

…..Before Fitzgerald, girl singers were typically relegated to a single chorus of a song; following Ella’s example, the “canaries”—as the girls were called—flew higher, especially after Fitzgerald’s swinging rendition of a classic children’s nursery rhyme, “A-Tisket A-Tasket,” became a global hit in 1938. Yet management dressed her up in schoolgirl clothes, boxing her into an image that overstated her innocence and compromised the achievements of a budding artist and innovator. Nevertheless, Fitzgerald’s drive to break new musical ground won the day as she programmed more adult fare into her act: after Webb died in 1939, she became the official conductor of the orchestra. In 1940 she said, “I used to sing nothing but jittery stuff but now everybody likes me to sing sweet songs, so I give ’em a little of each.”

…..Fitzgerald’s sweet and jittery musical transformations kept coming. In the mid-1940s she swerved into improvisational bebop as her personal avenue for change, digging deeper into scat and inventing complex fantasias on single tunes almost at will. Her phonographic memory allowed her to become a one-woman jam session. “That’s what gave us females permission to dig in and do some improvising ourselves,” said Betty Carter, a sister improviser. “It was no longer a man’s world.” She treasured her stylistic breadth. “What is the Ella Fitzgerald style today?” Ebony magazine asked in 1949. In the 1950s, touring as a member of the popular Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP) ensemble, Ella joined a troupe of soloists, seizing the stage and announcing her arrival as a vocalist of astonishing agility. As keyboard legend Oscar Peterson recalled in his 2002 memoir, in the joint finales of a JATP concert, competing with the horns, she gave no concessions, she played “rough”: at one of these performances, tenor saxophonist Lester Young turned to Peterson and said, “You stay out there long enough and Lady Fitz will lay waste to your ass!”

…..And yet her soaring popularity notwithstanding, it was with those Song Books that Ella surpassed even herself, performing an artistic feat that would have been remarkable if attained by any artist, let alone a Black woman. She transformed the culture of an entire repertoire, deftly infusing with swing the sophisticated show tunes from the golden age of Broadway musicals from the 1920s and ’30s—shows that had left their mark on the Great White Way, an apt nickname for a cultural institution that had routinely excluded Black artists from its stages. Through those eight Song Book albums, Fitzgerald dominated a category of standards, recording more than 250 of them. What lent the Song Books special authority was the way they enabled Fitzgerald to ignite a double transformation: by reinventing herself as a singer, she transformed a vintage repertoire; and by modernizing it, she laid the foundational stones for what would soon be known as the Great American Songbook. One transformation begat another.

…..In the wake of her Song Books breakthrough, Ella enjoyed worldwide acclaim—not just as a popular singer whose appeal easily crossed geographical and cultural borders, but also as a classical artist who provided a creative paradigmatic model for others, especially for the female singers populating the field, and even more especially for African American artists.

…..This brings me to the title of this book, Becoming Ella Fitzgerald. Over the course of my research, my purpose underwent its own transformation. When I initially conceived the title Becoming Ella, I thought that the Song Books had vaulted Fitzgerald into that rare sorority of single-named artists. But that premise changed when I realized that, prior to the Song Books, she had already been “Ella” among Black Americans and the jazz world. Between 1933 and 1950, she performed mainly but not exclusively for Black audiences in ballrooms and then in Black theaters (in “colored show business,” as it was widely known during the Jim Crow era), then moved into jazz clubs catering mostly (but not exclusively) to white audiences in the latter part of that era. The same model of diversity applied in her post–Song Book decades. In the 1960s, she continued her artistic evolution as she perfected the hybrid idiom of jazz-pop, experimenting with adaptations of soul while also deliberately engaging with a new generation of songwriters whose work she believed deserved the appellation “standards.” She insisted on reaching out to younger audiences, her lifeline to relevance. “I’m not going to be left behind,” she said throughout the decades. “If you don’t learn new songs, you’re lost. I want to stay with it. And staying with it means communicating with the teenagers. I want them to understand me and like me.”7 Across her entire career, the artist was always “becoming Ella Fitzgerald.”

…..Though her trajectory made her a “mixed singer,” as she once described herself, she flourished in collaboration with the great jazz instrumentalists of her era. In this stretch of her career, in the late 1960s Fitzgerald reached a peak of excellence touring with Duke Ellington, pushing many of his lesser-known songs into the jazz playbook. (Her stature as the foremost interpreter of Ellington’s vocal repertoire is only now, in the twenty-first century, being fully appreciated.) When age changed her voice in the 1970s, her decades of cumulative interpretive wisdom allowed her to adapt and innovate through new collaborations, particularly with Count Basie and the guitarist Joe Pass.

…..Becoming Ella Fitzgerald thus chronicles a continuum of self-invention and resistance to a “category,” to use Duke Ellington’s favorite term. She embraced hybridity. Diversity became her core identity, and surprise the wings of her imagination. Over a remarkably long career of sixty years or so, she fearlessly explored many different styles of American song through the lens of African American jazz. She treated jazz as process, not confined to this idiom or that genre. And through her own transformative quests as an artist, she changed the trajectory of American vocal jazz in this century.

.

,

___

.

.

Excerpted from Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song by Judith Tick. Copyright © 2024 by Judith Tick. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to read other book excerpts

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.

.

.