.

.

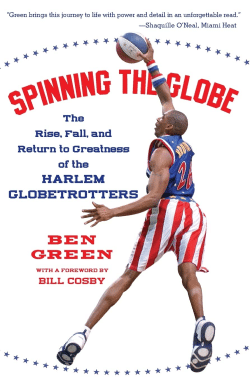

In this 2005 interview, Ben Green, author of Spinning the Globe: The Rise, Fall, and Return to Greatness of the Harlem Globetrotters, discusses the complex history of the celebrated Black touring basketball team.

.

.

___

.

.

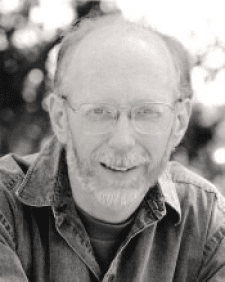

Ben Green, author of Spinning the Globe: The Rise, Fall, and Return to Greatness of the Harlem Globetrotters

.

___

.

Before Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, Julius Erving, or Michael Jordan — before Magic Johnson and Showtime — the Harlem Globetrotters revolutionized basketball and spread the game around the world. In Spinning the Globe: The Rise, Fall, and Return to Greatness of the Harlem Globetrotters, author Ben Green tells the story of this extraordinary franchise and iconic American institution.

Green chronicles the Globetrotters’ rise from backwoods obscurity during the harsh years of the Great Depression to become the best basketball team in the country and, by the early 1950s, the most popular sports franchise in the world.

Green chronicles the Globetrotters’ rise from backwoods obscurity during the harsh years of the Great Depression to become the best basketball team in the country and, by the early 1950s, the most popular sports franchise in the world.

Through original research, Green also uncovers intriguing controversies about the Globetrotters’ origins, their image in the African American community, and how they were used as a propaganda weapon during the Cold War. Green renders captivating portraits of founder Abe Saperstein and the players who defined the Trotters’ legacy, including Inman Jackson, Goose Tatum, Marques Haynes, Meadowlark Lemon, and Curly Neal. He also describes the Trotters’ struggles to overcome racial discrimination and internal dissension on their long road to glory as well as details their fall from grace to the brink of bankruptcy in the early 1990s, and the ultimate rebirth under owner Mannie Jackson.#

Green talks about the Globetrotters with Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita in a September 26, 2005 interview.

.

/

___

.

.

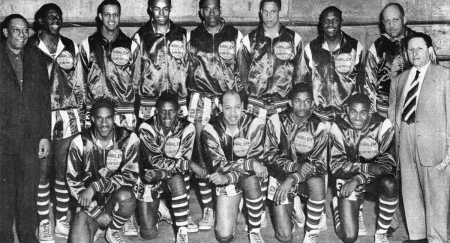

photo via Wikimedia Commons

The Harlem Globetrotters, c. 1950. The owner, Abe Saperstein, is on the right

.

“The Harlem Globetrotters were not just a great barnstorming team; they were a sociology class on wheels, bringing black hoops and black culture to a hundred Midwestern towns that had seen neither, and in the process transforming Dr. James Naismiths stodgy, wearisome game which was still sometimes played in chicken-wire cages by roughneck immigrants with flailing elbows and bloodied skulls, a sport more resembling rugby into an orchestration of speed, fluidity, motion, dazzling skill, and most improbably, inspired comedy.”

– Ben Green

.

_____

JJM You wrote, “Abe Saperstein is the most incongruous figure that one could conjure up to be the owner of this team. He and his players are a juxtaposition of opposites, as different as any human beings could be.” There are varying stories about how the Harlem Globetrotters began, aren’t there?

BG That was the big mystery going into this book, and I think I have come the closest anyone has in answering this question. It became clear early on in my research that the official story Abe told for thirty years was complete nonsense. He claimed that the team grew out of Chicago’s Savoy Ballroom, but that couldn’t have possibly happened because the dates were all off — for example, the Savoy didn’t even exist at the time he said the team began playing.

There is a version that makes sense, however. There is no doubt that a black basketball team called the Globetrotters existed in Chicago, begun by a man named Tommy Brookins. The team was in fact listed in the Chicago Defender as “Tommy Brookins’s Globetrotters.” Brookins’ story, told years later, is that his team needed a white booking agent because they wanted to get out of town and play in places like Minnesota and Wisconsin. Since Saperstein had done bookings for Negro League Baseball, they hired him. It is at this point in the story where it gets a little controversial because Brookins claims that Abe, in essence, stole the team because he started double booking the team — the second team of which was being booked under his name. But since Brookins didn’t want to be a player on the road anymore, he reconciled with Abe, gave him his uniform, and went back to Chicago.

JJM Your book reminded me that the Harlem Globetrotters were not from New York, but from Chicago.

BG When I started the book, I didn’t know any more about the Globetrotters than anyone else — all I knew was Meadowlark and Curly and, as a kid, watching them on CBS Sports Spectacular, Wide World of Sports, or Ed Sullivan. I just assumed they were from Harlem, and I also had no understanding about how long they had been around. I figured they were somewhat contemporary with my childhood, and was quite surprised to find out that they started in the late twenties.

JJM Why did Saperstein choose to attach the name “Harlem” to them when they were actually from Chicago?

BG. The most famous black barnstorming team at the time was the Harlem Rens, who were alternately known as the New York Rens. It is likely that Saperstein was trying to tag along on their glory a little bit. But more importantly, he wanted to be sure that when his team showed up in the little towns of Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Iowa and other states, everyone would know the Globetrotters were a team made up of black players. Because Harlem was the capitol of black America at the time, people would automatically know they were a black team.

JJM You wrote that in the early twentieth century, basketball was known as “the sport of Jews.” Talk a little bit about that, would you?

BG That was another interesting thing I learned while writing the book. When the Globetrotters started in the late twenties, and all through the sixties, baseball was considered America’s national pastime, while basketball was probably the third or fourth most popular sport behind horse racing and boxing — at least during the thirties. Baseball had a rural, pastoral ethos that required a lot of land on which to play it. Basketball, on the other hand, was a city game, and when waves of Jewish immigrants began arriving in New York and Chicago, the Jewish settlement houses and community groups who wished to assimilate young Jewish boys and girls into America through sports did so by playing basketball. All you needed to play the game was a makeshift hoop and a round ball. The game quickly caught on in the urban neighborhoods, particularly where Jews lived. Jewish community groups promoted it as a sport that Jews could play because a participant didn’t have to be some hulking Bronco Nagurski type — a player could be short, fast and quick. They were also very deliberately trying to counter the stereotype of Jews being people of books, and as intellectuals who couldn’t play sports. As a result, basketball became very popular. It is interesting that the most famous of all the basketball teams during the twenties was the original Celtics from New York, on which all the players were Jews.

JJM Did Abe Saperstein immediately see the business possibilities in basketball?

BG I really give Abe a lot of credit — he may have been one of the best sports promoters in history. He had a vision to see way beyond this little team from the south side of Chicago that traveled around in his Model T, struggling to survive for years and years. I think he realized that there was money to be made out there in the heartland, and it is a reason why the Globetrotters got in to the showmanship — he understood the importance of having a marketing angle that distinguished his team from any other run-of-the-mill barnstorming team.

JJM Given the era in which they began, it is pretty safe to assume the Trotters needed a white manager in order to set up games in rural America

BG Yes, I don’t think they could have ever survived in white America trying to book their own games. Abe was the front man who marketed and booked the team. In some sense, he was a one-man show for a long time as the team driver, promoter, and manager. For a while, he was even the sixth man off the bench when they needed him. An interesting thing about this is that from the time he started the team in 1928, and until 1934, the Globetrotters were not his team — it was a cooperative deal and they lived purely on the gate receipts that they split. The first big crisis in their history came in 1934, when Abe decided to make it his team, and make the ballplayers employees instead of partners.

JJM As a result of this move, the players went from making about fifty dollars apiece per game to around eight

BG Yes, and the entire team blew up on him. His star quit, the players quit, and Abe was forced to fold their tour and return to Chicago to recruit new players before going back out.

JJM When they went to these small towns of the Dakotas and Minnesota and Iowa and Montana, who did they play against?

BG The local team made up of guys from the local brake factory, the teacher’s school, the men from the Kiwanis Club. Whoever was there, the Globetrotters showed up to play them. The amount of territory this team covered is so very fascinating to me. I got an old United States highway map from the thirties just to see the back roads that they had to travel just to get to the towns in which they played. They played one hundred fifty games a year, non stop between November and April, traveling these back roads in an unheated Model T, in the dead of winter in the coldest part of the country. It is just unbelievable to think of how they lived, except when you put it in the context of the times — which was during the middle of the depression — and playing basketball seems like a pretty good way to try to survive. They could have been standing in some bread line instead.

JJM It is amazing that they survived the economic challenges of the Depression, not to mention that era’s racism.

BG That’s right. While they weren’t playing in the deep South, they still had incredible challenges. Where do they eat? Where do they sleep? There were not many hotels or restaurants to begin with in the middle of the wilderness in which they traveled, and quite often they couldn’t find a place to eat or sleep. They would have to find a grocery store, enter it through the back door, and quite often all they would get to eat was some cheese and crackers and sardines, and then get back out on the road. They called this way of life “living off the grocery.”

JJM Add to that the challenges of finding dependable transportation. As you said, driving in the dead of winter couldn’t have been easy.

BG I cant even imagine. Last October I went out to the Globetrotter training camp and asked five of the current players to simulate the experience of what it would be like for five of them — and a sixth in the form of Saperstein — to ride in a vehicle the size of a Model T. I measured out the dimensions and then stuffed them all basically into a chair. You can imagine the difficulty of that. The car’s top speed was about thirty-five miles per hour, there was no heat, no defroster, no shocks, no springs, and they were stuffed into it for hours and hours. When they finally got to their destination, they had to pile out of the car and play a basketball game, and when it was over, piled back in and take off to the next town. It was an incredible life.

JJM Saperstein always looked ahead, and a key to his survival was his relationship-building skills — not just with the people he booked games with and who his team played against, but also with the sportswriters, who were key in building interest for the game at the local level.

BG Saperstein sort of set the standards for a sports team owner building relationships with his customers. He befriended as many people as he could — promoters, high school basketball coaches, anybody that had a church basement or a barn with a hoop in it, the local Kiwanis Club — anywhere a game could be held, Abe built a relationship there. And as you say, he built relationships with sportswriters in every little town — relationships that lasted for decades. Sportswriters loved him, local promoters loved him, and they invited the Globetrotters back to their community year after year after year. They knew they could count on him, and they loved the guy. He had that kind of relationship virtually everywhere he went.

JJM Regarding that, you wrote, “The Trotters still wanted to win, but, more important, they wanted to give the crowd such a good show that they would be invited back.”

BG Yes, besides the obvious entertainment factor, their showmanship was also an important factor in their success because it allowed them to take a breather, as well as keeping the score down. While the crowd was entertained by the players’ passing abilities, what they may not have realized is that this gave them a chance to take a rest while also running time off the clock. They would typically get eight or ten points ahead and, because there was not a twenty-four second clock at the time, they could stall the entire game away from that point on if they wanted to. Since this strategy also kept the score down, the crowd remained entertained, the opposing players didn’t feel humiliated — and in fact left them believing they could beat them in a rematch — and they would get invited back to play again year after year.

JJM Two of the earliest stars of the Trotters were Runt Pullins and Inman Jackson, who, as you write, “ heralded the creation of two Globetrotters icons: the dribbler and the showman.” What were their trademark plays?

BG Inman Jackson was their first big man. He was only six-foot-three, but to put that into perspective, he was often described in old newspaper accounts as a “giant.” His size enabled him to dominate the game if for no other reason than because during that era they had a center jump at half court after every basket. He controlled most of the tips, and during one game he got every single jump ball. Jackson started the showmanship of the Globetrotter pivot men, and did a variety of ball handling tricks, including palming the ball, which was a difficult thing to do since the ball was bigger and the players were smaller then. He would do a windmill move and wave the ball around his head, putting the ball on his opponent’s head, and he would also roll it between the legs of the player guarding him, even going so far as stuffing it under his jersey. The Globetrotters of today are still doing some of the tricks that Inman started in the early thirties. Runt Pullins was the first great dribbler who did some of the things great dribblers of today do — bouncing the ball up high, then down to two inches off the ground, and then between his legs. He was also a great shooter, and could make shots from way outside. He was the player who began shooting the ball from half court. It is remarkable how the traditions these two players began carried on throughout their history, and are still being performed today.

JJM As Jackson and Pullin became more adept at entertaining, you wrote of the Globetrotters, “More and more, comedy was getting top billing over basketball.” It is clear that they performed during a time that whites laughed at their clowning, and some of their success can be attributed to how they ratified the stereotypes whites had of blacks of the era. How do you think the players felt about their comedy antics receiving more prominence than their basketball skills?

BG Unfortunately, all of the original players are long gone, so it isn’t really possible to know. The oldest Globetrotters who are still alive played during the forties, and I talked to many of them, as well as the players since then. One of the most fascinating aspects of this entire Globetrotter story is the minstrelsy they performed, and how it led to their Uncle Tom image. There was a great deal of discussion, particularly in the black press, about whether or not the Globetrotters were a minstrel show, and whether or not their work portrayed a degrading image of black athletes. Some thought that they were just a setup for whites to laugh at blacks.

In the book, I wrote a little about the history of minstrelsy — which goes back to colonial days, and which was one of the most popular art forms in America at the time the Globerotters started. Their popularity came at the same time as that of Amos ‘n Andy and Stepin’ Fetchit. Saperstein played up the minstrel, Stepin’ Fetchit image of the Globetrotters as a way to, in his view, give them an angle that differentiated them from other basketball teams. So, it is tough to know how the original Globetrotters felt about this, but some of the guys I interviewed who played in the sixties and seventies were aware of this, and they talked about trying to hold themselves up as ballplayers rather than clowns. One guy who played in the sixties and seventies with Meadowlark Lemon said that Meadowlark was a clown, doing all of his Amos ‘n Andy stuff, but the rest of the players did their best to hold themselves up with some dignity as ballplayers. But throughout their history, this was a very touchy issue.

JJM The Trotters became very popular on television, and viewers like me were left with the impression that they loved their work; yet you wrote, “The more popular they became the more disenchanted the players became.” So, it seemed as if the public perception of the Trotters was quite different from their private reality.

BG Yes, and that was certainly true by the late sixties and seventies, but the complexities of this issue developed in the thirties, when the entertainment value became more important than the basketball, and the question of their identity came up. What were they, a great basketball team or a group of clowning entertainers? I think you can argue that they were the best basketball team in the country when they beat the Minneapolis Lakers two years in a row. Following that — and throughout much of the fifties — they were playing legitimate games against College All-Americans, so the case can still be made that their primary identity was that of a terrific basketball team. By the sixties and seventies, as they got more television exposure, they got away from their basketball roots, which was that of being a great basketball team who could also put on a show toward the end of the game. It got to the point that the show as all that was left, and I believe that is what ultimately led them to the brink of bankruptcy.

JJM Another reason for their relying so heavily on the entertainment aspect is that it differentiated their product from that of the NBA. That may have been the only way for them to get the attention of the fans

BG Yes, and by the sixties and seventies they were only playing stooge teams — they weren’t even playing legitimate games anymore — and it didn’t matter if you were a great ballplayer, it only mattered whether or not you could clown around and knew the gags and the routines. What is ironic about this is if you look at the NBA of today, part of their success is because they began playing Globetrotter-style basketball. The Lakers’ “Showtime” style of ball during the ‘Magic’ Johnson era was really Globetrotter basketball. The weave, the fast break, the slam dunks — all of these things were what differentiated the Globetrotters from the straight white teams of the forties and fifties. By the seventies and eighties, that style was all over the NBA.

JJM People remember Julius Erving’s showman-like impact on the NBA, but the guy I remember as having an almost shocking effect on the fans was an ex-Globetrotter, Connie Hawkins.

BG Yes, that’s right. I remember that too.

JJM One of the Globetrotters’ biggest rivals of the thirties was the New York Rens. How did that rivalry develop?

BG Saperstein realized that if he was going to be successful, the Globetrotters would need a rival. At the time, the Rens — the original Celtics — were considered one of the best basketball teams in the country, and for three of four years, Abe challenged them to a game. By doing so, he would whet the appetites of the fans and raise the value of the Globetrotters.

As the time that these two teams got close to playing one another for the first time approached, the Rens really looked down on the Globetrotters. For the owner of the Rens, he took the Globetrotters challenge personally because he felt that the Trotters were nothing more than a bunch of clowns — that they were minstrels, basically. The press picked up on this, and also felt that the Globetrotters weren’t serious players, that they were nothing more than a bunch of showmen. So the controversy around these two teams built up until 1939, the year they first played against one another at the World Professional Basketball tournament in Chicago. While the Rens won, the game was much closer than anyone could have expected. The following year they played again, only this time the Globetrotters beat them right at the end of the game. After that game they established that they could play with just about anybody.

JJM Was the 1939 game between the Rens and the Globetrotters much of a story in the white media?

BG No. As I mentioned, in 1939 basketball was not that big of a deal. While the World Pro Tournament was being held in Chicago, the big story in the Chicago papers at the same time was the opening of baseball spring training, as well as a horse race and a boxing match that was taking place in the area. It was a time that professional basketball was still fighting for credibility, and black basketball was completely ignored by the white media, which is why my newspaper of record during my research was the Chicago Defender, with the Pittsburgh Courier as a backup source. The only way to get information about the Rens was through the black press.

JJM After the first loss to the Rens — a game much closer than anyone had really expected — Saperstein rebuilt the team. What kind of player did he look for?

BG He felt that in order to compete with the Rens, the Globetrotters had to get bigger, stronger, and faster. They basically needed better players. The Rens had a monopoly of sorts on the best black ballplayers on the East Coast, and the Globetrotters got their players mostly from Chicago, Detroit and the cities of the Midwest. With players from this area, he revamped the team, got himself better players, and actually beat the Rens the following year, 1940, at the World Pro Tournament.

JJM Their other great rivalry was with the Minneapolis Lakers, whose best player was the center George Mikan. Returning to this issue regarding racial stereotypes and minstrelsy, you wrote, “The rumblings of the civil rights movement are still faint, barely audible in the distance, but in another four years, in the upsurge of the Brown decision and the Montgomery bus boycott, Abe Saperstein and the Harlem Globetrotters will be pulled inexorably into that swirling vortex, will come under stinging attacks, from blacks and whites alike, for being Uncle Toms and Sambos, Stepin Fetchits in short pants.” Why didn’t the Trotters’ wins over the Lakers help break down this image of theirs?

BG In some ways it did. For one, the Globetrotters’ wins over the Lakers sealed the fact that they could play ball with anybody. From 1948 and throughout the fifties and early sixties, people knew they could play. Besides playing the Lakers, they played an entire series of games with College All-Americans, who were put on the road with the Globetrotters. The games sold out from one end of the country to the other.

Their image beyond basketball continued to take a hit because of what was happening in the civil rights movement, and by the sixties and seventies, the black community had fully turned on the Globetrotters. At that time, all kinds of issues of black identity — everything from hair styles to how to refer to the race itself — was up for grabs. So, the image of Meadowlark Lemon left an impression of the Globetrotters’ “Tommin’ for Whitey” that really haunted them at this point in time, and the black community turned against them. This is in stark contrast to the times they beat the Lakers in 1948 and 1949, when they were heroes to the race. The black community revered them in the same way they had for Jackie Robinson or for Joe Louis because the Globetrotters proved they could beat the best white team in the country. But later, when all the racial issues of the sixties came to the forefront, the Globetrotters were seen as a relic of the past.

JJM The Globetrotters faced a complex dilemma because while they broke down some of the fears whites had about blacks — which at the time was very essential — they did so at the expense of their image with black Americans. Basically, they were damned if they did and damned if they didn’t.

BG Some of the most interesting comments I heard on this subject were not from the ballplayers, but from their African American fans. I asked one guy who attended the 1948 and 1949 games against the Lakers if he felt like the Globetrotters’ show was at all demeaning, and he said that, to the contrary, they waited for the show because that was the affirmation of how good they were. But what eventually happened during the seventies is that the show was all that was left — the good basketball was gone because the best ball players were by that time playing in the NBA. The Globetrotters were left with the clowning, and the fans also knew that opponents like the Washington Generals were not legitimate, which meant they lost all credibility with their fans. They went from boasting about beating George Mikan so bad that they could put on their baseball routine at the end of the game, to only having the clowning played out in front of stooge teams. To the Globetrotters of that era, beating the Lakers was their final triumph.

JJM Everybody dumped on the Trotters. Even the novelist James Michener wrote, “What these blacks were doing for money was exhibiting proof of all the prejudices which white men had built up about them. They were lazy, and gangling, and sly, and given to wild bursts of laughter, and their success in life depended upon their outwitting the white man. Every witty act they performed was a denigration of the black experience and dignity In fact, I strongly suspect that the Harlem Globetrotters did more damage racially than they did good, because they deepened the stereotype of the lovable, irresponsible Negro.” While reading about this part of the Globetrotters’ history, I couldn’t help but think of how Louis Armstrong struggled with the same kinds of complexities they did. Like the Globetrotters, through his great art and charisma Armstrong was effective at breaking down fears and stereotypes the white audience had toward black performers of his era, which served to elevate the potential of other blacks but simultaneously limited his own.

BG That is a great analogy because there is no doubt that within the black community people knew Armstrong had great chops and they understood his importance, but the more he sang songs like “Hello Dolly,” it must have seemed he was playing for the acceptance of a white audience — but could this same audience accept John Coltrane?

JJM That’s right. Within a year of Armstrong recording “Hello Dolly,” Coltrane is recording A Love Supreme. It is difficult to imagine two more different perspectives of African American life at that time. It certainly doesn’t mean Armstrong’s view was unacceptable or should be considered demeaning, but what can be learned from this is that he set the stage for Coltrane to do things he himself could not.

BG That is a very interesting analogy. An athletic comparison can be made regarding events of 1968, which was the year Tommy Hines and the African American sprinters at the Olympics made their black power salute during the awards ceremony. At the same time, Meadowlark Lemon and Curly Neal are shuckin’ and jivin’ on Wide World of Sports, which led many in the black community to conclude that their clowning was not the image they cared to look up to. Television played to that, because they weren’t interested in showing a Globetrotter basketball game — they were interested in showing Globetrotter entertainment.

JJM Another interesting dynamic of this entire story is the growth of the NBA. How did Saperstein deal with the NBA once they began drafting black players?

BG As with every other issue involving racial questions with Abe, this is a very complicated story. I was amazed at discovering what an important role the Globetrotters played in keeping the NBA afloat during its early years. A case could be made, in fact, that before the arrival of Bill Russell, the NBA may never have survived if it hadn’t been for the Globetrotters. NBA owners were practically begging Abe to come in and play doubleheaders in order to draw big crowds. One game at Madison Square Garden drew nineteen-thousand people, and it was clear they came to see the Globetrotters and not the Knicks versus the Warriors, because when the Globetrotter game was over, the stands were practically empty. It was not uncommon for arenas to clear out after the Globetrotter pre-game exhibition — one former NBA player told me that when Trotter games were over, the only people left in the stands were the peanut vendors and the ticket takers. So, for years, the Globetrotters helped keep the NBA alive.

At the same time, when the NBA started drafting black ballplayers, the one person who had the most to lose was Abe Saperstein, because his monopoly on quality black ball players was gone. He was on top of the world, and had actually bought out his old rivals, the Rens. But once he started losing the best talent to the NBA, it became a competition with them that the Globetrotters lost.

JJM Bill Russell was such a critical figure in the future of the NBA and of the Globetrotters. You point out that Saperstein was having some success in luring Russell to the Globetrotters, but he messed things up when he showed him a porn magazine, thinking that would entice Russell in some way

BG True, but he got Wilt Chamberlain because Wilt realized that while the NBA was a big deal, the Globetrotters were more popular and playing for them could take him all over the world. Chamberlain played for the Globetrotters his first year out of college, and after he joined the NBA, came back for another twelve seasons during the summer months. Abe went after a number of players, including Russell, Oscar Robertson, Cazzie Russell — he lost them all to the NBA, but he could still outdraw them on television. Even as recently as the late sixties, the Globetrotters were getting a bigger audience share when they were on Wide World of Sports than the NBA would for their network television games.

JJM I am going to mention a handful of names, and would like for you to tell me the first thing that comes to mind about them. The first name is Sonny Boswell.

BG When we talked earlier about Abe rebuilding the team following their loss to the Rens, Boswell was the key addition. He was the best shooter in basketball, a long range bomber, and a complete ball hog who couldn’t play a lick of defense. Boswell was a one-dimensional player, but he took them to a world championship on the strength of his long range shooting. He was a pure shooter from “downtown,” as they say today.

JJM Bob Karstens.

BG While Saperstein played with the Globetrotters off and on as a substitute during the early years, Karstens was the first full-time white Globetrotter. When Goose Tatum — the greatest showman of them all — and many of his other players got drafted into the military in 1943, Abe just about had to shut the team down. He went after Karstens — a trickster who played with the House of David — because he could do all their ball handling tricks. In fact, Karstens invented a lot of the tricks they still do in the magic circle. Karstens played with them full-time for about a year and a half until Goose got out of the Army.

JJM Marques Haynes.

BG Marques was undoubtedly the best dribbler in Globetrotters history, and I could make the case that he may have been the best ball handler in the history of basketball. He created a whole style of ball handling no one had ever done before, and the great thing about his dribbling is that it was purely spontaneous. In essence, he would challenge his opponent to come get the ball. In the days of Curly Neal, everything was basically orchestrated — his opponents knew he was going to slide one way and then the other, and they would stay out of his way. But everything Marques Haynes did with a basketball was done spontaneously. His influence was felt by later generations of players, going all the way to Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas.

JJM Goose Tatum.

BG Goose Tatum is the most fascinating character in the whole Globetrotter story. Inman Jackson was the first showman, but Goose was the guy who invented Globetrotter basketball in the way people think of them today. He came up with all the great tricks and gags, and was spontaneous as a showman in the same way Marques Haynes was as a dribbler. Everyone who played for the Globetrotters after Goose — Meadowlark Lemon certainly included — tried to imitate Goose. While he was the great showman of the team, in some ways he was also its most tragic figure, particularly regarding his personal life after leaving the team. He took the Globetrotters to the promised land, got them to national television, and then walked out on them in the middle of the night, eventually starting his own team.

JJM Yes, his was a heartbreaking story

BG His sixteen year old son was killed in a car accident while traveling with Goose’s team, and at that point Goose just drank himself to death. He was dead the next year.

JJM Meadowlark Lemon.

BG Meadowlark Lemon’s story was one of the most surprising to me, because when I was a kid, I really looked up to him — so much so that I would even imitate his hook shot when playing the game myself. He was the showman of the team at that time, but I could find almost no one inside the organization who would say good things about him.

Two things about Meadowlark came across the strongest, the first being that he really couldn’t play basketball. Abe brought him in because he needed someone who could imitate Goose — which goes back to our conversation regarding minstrelsy. When Goose left the team, Abe grabbed on to Meadowlark because he looked like Goose and could imitate him on the court — but the move lost the respect of the other ballplayers. Meadowlark’s entire role was to imitate what Goose did, but the other players said he couldn’t do it nearly as well as Goose. The real resentment of Meadowlark occurred around television. While Goose took them to the TV stage, Meadowlark became the international celebrity — a worldwide figure of sorts because of all their exposure. The Globetrotters then turned into the “Meadowlark Lemon Show,” and the other players really resented that. He was a maniac, he was arrogant, he became the president, he became the coach, and he just dominated the whole show. He was, in a way, symptomatic of what led the Globetrotters to bankruptcy, because their entire existence was centered around the clowning. With Meadowlark, they got totally away from their roots.

JJM Yes, he had a massive ego, something that impacted the relationship between Saperstein and the players as well. At one time Abe was incredibly devoted to his players and treated them as equals, but as he became more popular and wealthy, he put himself way above the players. They must have resented that.

BG There was a lot of resentment around that. Some guys loved Abe until the day he died, but for others, they really felt the separation. The old days of Abe sleeping with them in the Model T or in some flea bitten hotel were long gone. He was now a millionaire and would stay in a different hotel. The players may have still been in the flea bag hotel, but he was in the fanciest place in town.

JJM You wrote, “In truth, the Globetrotters are more accessible to the average fan than other sports heroes. None of us can hit a fastball like DiMaggio, steal home like Jackie Robinson, or throw a right with the power of Joe Louis, but every kid in America who has ever picked up a basketball has tried to dribble like Marques and shoot Goose’s hook. We have all been Globetrotters.” When did that fantasy end?

BG I am not sure it has ended, although it certainly disappeared for a while. When I was a kid, I tried shooting a hook like Meadowlark, and tried dribbling like Curly, and I think that is where the “we have all been Globetrotters” image came from.

JJM The team was on its death bed ten years ago, wasn’t it?

BG Yes they were, and that is when Mannie Jackson — a former Trotter, but more importantly a Honeywell executive — brought them back in a big way. While they may not be on network television like they once were, today they are playing in front of millions of fans a year. They are once again incredibly popular all over the world — for example, they will be playing in sixty games this year in China alone.

While writing this book, I followed them around and went to many of their games, and that experience tells me there are likely many little kids out there imitating the moves of the Globetrotters today, which is because Jackson got them back to doing what they do best — playing good basketball. My six-year-old nephew went to see them this year and he was blown away by the basketball, the dunks, the behind the back passes. On top of that, he laughed his head off. The unique quality of the Globetrotters is that they play terrific basketball, make incredibly athletic plays, and make you practically fall out of your chair in laughter. They are the best of both worlds.

My sense is that there are kids all over the world trying to be Globetrotters. There was an article on Yao Ming in Sports Illustrated recently in which he said he was bred to play basketball, but he didn’t want anything to do with it until after he saw a Globetrotter game when he was about ten years old. It was then that he first realized the game could be fun.

JJM That reminds me of how the State Department used the Globetrotters during the Cold War years as a way of exporting all kinds of propaganda about how blacks have made it in America, as well as exporting the game of basketball

BG That was another fascinating aspect of this story. When America exposed them to the world as examples of African Americans achieving success in this country, the difference between the way they were treated overseas versus here in the United States was striking. They were paraded through the streets of Rome and Paris, where they were put up in the best hotels, but when they returned home, they couldn’t even get a hamburger or find a decent hotel to stay in. When they played in my hometown of Tallahassee, Florida in the mid-fifties, they couldn’t even find a hotel — they had to go sleep in the dorms of a black college. The disparity between the way the Globetrotters were used to represent America overseas to counteract Soviet propaganda, compared to the reality of Jim Crow was very striking.

JJM The great jazz musicians who made the State Department tours had many of the same experiences.

BG Yes, I remember reading a story about Dizzy Gillespie, and how the black musicians were used in the cultural propaganda war with the Soviet Union.

JJM The Soviets were pretty traditional when it came to jazz, and found modern jazz as played by the likes of Gillespie as being somewhat decadent. Did they have trouble with the kind of basketball played by the Globetrotters?

BG I wouldn’t say that they did. In the first game played there, no one laughed at the gags, but that is because nobody explained to the Soviet audience that they were going to do a “show.” Because the Soviets took basketball very seriously, they couldn’t figure out what the Globetrotters were doing, and they didn’t get it at all. As a result, from then on Abe had an announcer tell the audience before each game that, while the Gloebtrotters are a great basketball team, they are also great entertainers. After that, everyone understood and they became a huge success.

JJM We were talking about the NBA earlier, and how the Globetrotters played a major role in helping the league succeed during lean times. Given all the trouble the NBA seems to be having in connecting to its fans today, do you get a sense that there might again be an appeal made by the NBA to have the Globetrotters participate in league events?

BG Absolutely. They are talking to each other and doing some joint ventures. David Stern understands the importance of the Globetrotters, and once said that in all the years he has traveled over the world for the NBA, whenever basketball is mentioned, people often still say “Harlem Globetrotters” because they were the introduction to the game for many people. The NBA is definitely reaching out, and vice-versa.

JJM Does the NBA view the Trotters as competition?

BG Early on in their history, the NBA looked at the Globetrotters as competition, but once they got so incredibly popular during the Michael Jordan era, they saw the Trotters as has-beens — which they came very close to becoming. The big future of the Globetrotters is overseas, and I think they have a chance to be much bigger there than the NBA because of the character issues the NBA is constantly dealing with. The image of the NBA beyond basketball — the arrests, the drug problems, the fights in the stands — is not the image the rest of the world wants for basketball. This is a big reason why China invited the Globetrotters to their country, because, in addition to basketball, they want the players to come into their schools to talk about character-building, values, and good sportsmanship. After all, that is what the Globetrotters are — ambassadors of goodwill.

Mannie Jackson has really brought that back — they go to schools and hospitals, they attend community workshops, they teach black history, and they do thirty minute autograph sessions after every game. Basically, they are reaching out to families in ways that the NBA doesn’t. Mannie Jackson told me that in the global market basketball now competes in, the Globetrotters will be number one or number two, and my hunch is that he is thinking he will be number one — above the NBA.

_________

Spinning the Globe:

The Rise, Fall, and Return to Greatness of the Harlem Globetrotters

by

Ben Green

.

.

_____

.

.

About Ben Green

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

BG I was crazy about sports, and was a big Mickey Mantle fan, so he would have been high on my list.

JJM Did you grow up in New York?

BG No. I was an Air Force brat until I was nine. At that time we moved to Tallahasse, Florida, where I have been ever since. I lived right behind the Florida State University football field, and I started hanging out with the players, many of whom quickly became my heroes.

*

Ben Green is the highly acclaimed author of Before His Time (the subject of a PBS documentary), The Soldier of Fortune Murders (which sold more than 100,000 copies and was the basis for a CBS miniseries), and Finest Kind. A former Bread Loaf Fellow, Green lives in Tallahassee, Florida, with his wife, Tracie, and two daughters, Emily and Eliza. He is a graduate of Brandeis University and is on the faculty of Florida State University.

___

Praise for the book

.

“Captures the drama of this rags-to-riches-to-rags-to-riches story, and gives the reader the sense of being there.”

– New York Times

.

“…an ambitious, engaging book on the history of the team and how they endured a range of barriers…moves seamlessly between the past and present-day Globetrotters.”

– Black Issues Book Review

___

.

.

This interview took place on September 26, 2005, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

.

___

.

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Jack Johnson biographer Geoffrey Ward

.

.

___

.

.

.

Click here to view all Black History Month Profiles

Click here to view all interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to read The Sunday Poem

Click here for information about how to submit your poetry or short fiction

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it ad and commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

* Text from publisher

.

.

.