.

.

photo by David Schull

.

Dunstan Prial,

author of

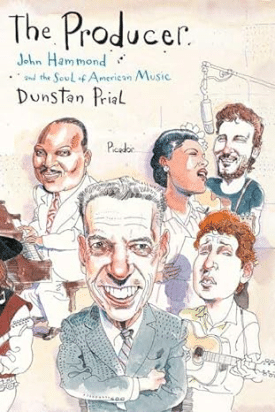

John Hammond and the Soul of American Music

.

.

___

.

.

John Hammond is one of the most charismatic figures in American music, a man who put on record much of the music we cherish today. A pioneering producer and talent spotter, Hammond discovered and championed some of the most gifted musicians of early jazz — Billie Holliday, Count Basie, Charlie Christian, Benny Goodman — and staged the legendary “From Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall in 1939, which established jazz as America’s indigenous music. Then as jazz gave way to pop and rock Hammond repeated the trick, discovering Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen, and Stevie Ray Vaughan in his life’s extraordinary second act.

Dunstan Prial’s biography The Producer: John Hammond and the Soul of American Music, presents Hammond’s life as a gripping story of music, money, fame, and racial conflict, played out in the nightclubs and recording studios where the music was made. It shows Hammond’s life to be an effort to push past his privileged upbringing and encounter American society in all its rough-edged vitality.

Dunstan Prial’s biography The Producer: John Hammond and the Soul of American Music, presents Hammond’s life as a gripping story of music, money, fame, and racial conflict, played out in the nightclubs and recording studios where the music was made. It shows Hammond’s life to be an effort to push past his privileged upbringing and encounter American society in all its rough-edged vitality.

A Vanderbilt on his mother’s side, Hammond grew up in a mansion on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. As a boy, he would sneak out at night and go uptown to Harlem to hear jazz in speakeasies. As a young man, he crusaded for racial equality in the music world and beyond. And as a Columbia Records executive — a dapper figure behind the glass of the recording studio or in a crowded nightclub — he saw music as the force that brought whites and blacks together and expressed their shared sense of life’s joys and sorrows.

This first biography of John Hammond is also a vivid and up-close account of great careers in the making: Bob Dylan recording his first album with Hammond for $402, Bruce Springsteen showing up at Hammond’s office carrying a beat-up acoustic guitar without a case. In Hammond’s life, the story of American music is at once personal and epic: the story of a man at the center of things, his ears wide open.#

Prial discusses Hammond’s life with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a November 20, 2006 interview.

.

.

___

.

.

photo via Wikimedia Commons

John Hammond in 1940

.

“I am still a New Yorker who owns no house, who thrives on city weekdays and country weekends. I still would change the world if I could, convince a nonbeliever that my way is right, argue a cause and make friends out of enemies. I am still the reformer, the impatient protester, the sometimes-intolerant champion of tolerance. Best of all, I still expect to hear, if not today then tomorrow, a voice or a sound I have never heard before, with something to say which has never been said before. And when that happens I will know what to do.”

– John Hammond

.

.

___

.

.

JJM Why did you choose John Hammond as the topic of your first book?

DP I wanted to pick a topic I was passionate enough about that would allow me to maintain my enthusiasm for a long period of time, and music is a great passion of mine — specifically the music of Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and Stevie Ray Vaughn. Once I found out that Hammond was involved with so many other great musicians in addition to them, I figured he was someone I could spend however long it took to get the book done.

JJM How long did it take for you to complete the book?

DP About five years.

JJM So, you knew Hammond through his connection to Dylan, Springsteen and Vaughan

DP That’s right.

JJM What did you know about jazz, and about Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, Count Basie and the other jazz musicians he worked with?

DP Absolutely nothing. I wouldn’t have known Benny Goodman from anyone. If you played a recording Goodman’s, Charlie Parker’s, and then Miles Davis’, I probably could have picked them apart, but I couldn’t guarantee it. That’s how little I knew about jazz prior to beginning this project. But that was part of the beauty of it, because I wanted to do something that would help me grow. I didn’t see the point of writing a book on someone like Springsteen or Dylan, who are artists I already knew a great deal about and so much has already been written about. One of the things that fascinated me and kept me enjoying this process was buying Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and Charlie Christian recordings, listening to them over and over again, and learning something about them and their music that I didn’t know before.

JJM So much of Hammond’s life was devoted to encouraging social reform. Who was his model for this?

DP There were two key people in his life concerning this. One was his mother, who was Cornelius Vanderbilt’s great granddaughter. There was a lot of money in his family, and as time went on, there was a sense among some of the Vanderbilt’s of wanting to give back. This feeling was particularly prevalent in his mother, who was involved in a number of social causes. The other key influence was his uncle, Henry Sloane Coffin, who at the early part of the twentieth century was one of America’s great protestant academic thinkers. As head of the Union Theological Seminary, he had a tremendous influence on Hammond. These family members helped promote his sense of progressive reform — it wasn’t like he looked at Teddy Roosevelt for this kind of awareness. It was handed down to him from members of his own family.

JJM An early experience with social reform came while he worked as a newspaper reporter in Maine

DP That job was where he was first able to combine a passion and a talent, which is really what his whole life was about. He was an excellent writer, and he often wrote best when he was angry. In this particular case, he went out to do a story on one of the Native American Indian tribes in Maine. Once he got to the reservation where they lived, he was deeply disturbed by their living conditions, which got him sidetracked from the story he was assigned to do. He was especially annoyed with the Catholic priests who were running the reservation and living like kings — they had plumbing and electricity while the Native Americans were essentially living in squalor. This offended Hammond, and the article he wrote about it landed on the front page of the Portland Evening News.

JJM Hammond is best known as a talent scout and producer, but he was also a journalist — a jazz critic for Downbeat and Metronome, as well as a writer for The Nation.

DP That’s right. His editor for the Portland Evening News was Ernest Gruening, who eventually went on to become a United States Senator and was a reformer in his own right. He was Hammond’s connection to The Nation.

During the Scottsboro trials, he called Hammond — who was in his early twenties at the time — and asked him to cover the trials for The Nation. He went down and wrote very articulate articles that described how the State of Alabama prosecutors could have put the case away in a manner that would have made everyone associated with the trials happy. Anyone in their right mind could have seen that a couple of the Scottsboro defendants were innocent. Hammond’s point in these articles was that anger and racism was so profound in the South that people were unwilling and essentially unable to let this thing go — that they had to keep the trial going until they got a result they felt vindicated their persecution of these kids. It ultimately led to them having a lot of egg on their face, because by the time everything was said and done, everyone in America realized what was going on. Hammond pointing out the racism that existed in the justice system took a lot of courage, especially considering he was all of about twenty-two years old. His work was not straight reporting, it was thoughtful opinion about what was going on and the ramifications this trial had for the South.

JJM How much did his political views impact his decision-making concerning music?

DP Quite a bit, but I don’t think he ever allowed his political agenda to sway him in terms of taste. One of the reasons we talk about John Hammond today is because he put Benny Goodman and Teddy Wilson on the same bandstand. He groomed Wilson to be the first black musician to play with white musicians in public — basically, Wilson was Hammond’s Jackie Robinson. He could have pursued this agenda in a way that politics overtook the music, but part of Hammond’s genius was that the combination worked. Matching Teddy Wilson with Benny Goodman not only made social history, it also made beautiful music. He was able to balance the political and musical aspects so successfully that we still talk about it today.

JJM He spent a lot of time as a young man in Harlem. What was his introduction to Harlem?

DP His sister confirmed that his introduction to the blues, jazz and, essentially, jazz music was through the servants in his house on the Upper Eastside of Manhattan. At some point, he probably learned from them that the music he enjoyed listening to on the radio or record player in their quarters was being played in clubs up in Harlem, which was only a fifteen minute bus ride from 91st Street. So, beginning around the age of nine, he took the bus and wandered all over Harlem, probably making a loop up from 5th Avenue, then west to 6th and 7th Avenues and about 134th Street, walking down a few blocks, and then coming back by 125th and passing by the Apollo, where he befriended the club’s doorman. His sister said this doorman took Hammond under his wing, and if it got too cold, too dark or too late, this guy would make sure that Hammond got back on the bus that would take him back to East 91st Street.

JJM Would he tell his parents where he was going?

DP Absolutely not. He would just walk around or stand outside the clubs and watch the musicians come and go. Toward the end of the evening he would go back to the Apollo and talk with the doorman awhile, then get on the bus and go home. He was clearly a precocious young fellow.

JJM Why did James P. Johnson’s recording of “Worried and Lonesome Blues,” in Hammond’s words, change his life?

DP I understand he said that about a few songs. He talked about that one, and he also talked about some Bessie Smith songs, and a Garland Wilson song. Different songs were mentioned as life-changing throughout his life. Stride piano like that played by Johnson was something Hammond loved all of his life.

JJM Garland Wilson was his first recording artist. What did he learn from the experience of working with him?

DP I don’t think he learned anything more than persistence. He handpicked Garland Wilson because he met him at one of the club’s that he was hanging around. By this time he was maybe nineteen or twenty years old, had dropped out of Yale, and was using his own money to sort of buy his way into the music industry, and Wilson was the first person he could get to record. While Wilson had recorded before, he was basically a “B” list pianist on the Harlem circuit, and he was the kind of artist Hammond could reasonably expect to work with at that stage of his career. He recorded a few sides, but I don’t think they were good enough for a record company like Columbia to pickup. This didn’t deter Hammond at all, because about six months later he went back to the studio with Wilson — using his own money — and recorded a couple sides that this time were good enough for Columbia to distribute. By now, Hammond had obviously learned something, because his next recording session was with Fletcher Henderson’s band, which was a very big leap even though Henderson was down on his luck at the time. So, Hammond was moving along quickly in his evolution as a producer and a figure in the music business.

JJM Not only was he learning the business, but he was learning how to advocate for himself as well, even if his actions were clear conflicts of interest — which was pretty obvious regarding the way he promoted the Henderson recording.

DP That was just the earliest example of what he did many times over the next ten or fifteen years.

JJM Specifically, concerning this 1932 recording by Henderson — produced by Hammond — he wrote in Melody Maker, “Not so long ago Fletcher and his band made ‘King Porter’s Stomp’ [sic] If that comes out, it may rightly be considered one of the most important discs ever made.”

DP Right, and he neglected to say that he produced that recording

JJM It seemed as if he felt he was above reproach

DP There is no question that he was an arrogant guy. When Hammond felt he was right, he simply felt he was right, and that’s that. In hindsight he was right a lot of the time, because when you listen today to the recordings he touted in the pages of the Brooklyn Eagle, Downbeat, and Metronome, you realize this is indeed great music. Does that make it right? Absolutely not.

An obvious objective of touting your own artists would be for monetary gain, but since Hammond didn’t need the money, he felt he was promoting them because he genuinely felt they were making the best music out there. I’m not arguing that it’s right, I’m just saying that’s how Hammond interpreted what he was doing.

JJM He may have also been doing it to create a certain stature for himself within the music business that money can’t buy.

DP He was not above self-aggrandizement.

JJM Hammond originally described Benny Goodman’s band as “merely another smooth and soporific dance combination.” A year later, he acted as Goodman’s agent for a recording contract. What changed his opinion of Goodman during that time?

DP Probably the fact that he started working with Goodman.

JJM How did he get in a position to work with him?

DP During the worst part of the Depression, the record industry in America was essentially down the toilet, so he went to England and put together a contract with the English unit of Columbia Records to record six American artists, five of whom he already had some contact with. Needless to say, he negotiated these contracts without telling any of the artists that he was doing this. The only wild card was Goodman.

When he returned to the United States with these contracts, he had to convince Goodman that they were real, and for him to make the recordings. As the story goes, Hammond chased Goodman down on 52nd Street and told him he had contracts for him to record some sides for the English unit of Columbia, to which Goodman responded by saying to Hammond, “You’re a goddamn liar.” Goodman thought he was being lied to because he couldn’t believe anyone was giving contracts for relatively unknown session men at the time, which is what he was at the time. It took Hammond a bit of time to explain to Goodman that he had gone to England, and through the contacts he had as a result of writing for Metronome, entered into legitimate contracts. Hammond was pretty persuasive and got Goodman on board. He soon began replacing a lot of Goodman’s band members, and one of the first people he brought to Goodman was the drummer Gene Krupa, who had been a favorite of his.

JJM At what point did he see that Goodman’s band could act as a catalyst for social change?

DP Hammond saw the growing popularity of Goodman’s band, but using his band as a catalyst for social change was sort of an odd pick because Goodman was two things, essentially; a businessman, first, and a musician, second. He was a businessman whose business happened to be music. But Goodman was not a risk taker. He grew up dirt poor on the south side of Chicago and had to drop out of high school to work and help his family make ends meet. In his early twenties, he was able to support his family by doing session work in New York, and his fledgling band was gaining popularity, so the last thing he wanted to do was rock the boat by adding black musicians to his band. He was not someone given to social experimentation.

The question of when Hammond saw Goodman’s band as a catalyst for social change is not something I can answer. Knowing that Hammond loved a challenge is an impractical reason — the practical reason is that Goodman was who he was closest to at the time. It took him the better part of two years to convince Goodman that this was the right way to go. The results were that bringing Teddy Wilson and, eventually, Lionel Hampton, into the band were not only good socially, but they made great music together. The argument Hammond used was that people wanted to hear great music, and they don’t care who makes it. Goodman wasn’t convinced at first but eventually saw that Hammond was right. This showed pretty quickly, because the music they played together both in recording sessions and live was widely accepted by the American public, who demonstrated they didn’t care that blacks and whites were playing together.

JJM What sort of relationship did Hammond and Goodman have during this time?

DP Goodman clearly trusted Hammond to make decisions about his music during this time, which is interesting because Goodman was a very controlling guy. They always had an up-and-down, mercurial relationship that could be described as a fraternal rivalry. It’s interesting that they got along and were able to do as much as they did because they often fought, and would swear to never work with one another again, but I believe when Hammond’s decisions proved to be correct, Goodman had a change of heart. From the beginning, when Hammond informed Goodman about the recording contract — during a time when very few American musicians were getting contracts — he could see that regardless of his methods, Hammond had the ability to get things done.

JJM Hammond had conflict with many of the great musicians of the era — those he managed and those he didn’t. A famous encounter was with Duke Ellington. Regarding Ellington’s “Reminiscing in Tempo,” Hammond wrote, “Ellington’s music has become vapid and without the slightest semblance of guts The Duke is afraid even to think about himself, his struggles, and his disappointments and that is why his “Reminiscing” is so formless and shallow a piece of music.” Why did he take on Ellington?

DP As Hammond’s biographer, I don’t defend his methods as much as his motives, and at times Hammond’s hubris caused him to be extremely heavy-handed. This is arguably the biggest instance of that. At the time he wrote this — in 1934 or 1935 — he was only in his early twenties and had recently dropped out of Yale. And, as a member of the powerful Vanderbilt family, he was basically given a yearly allowance the equivalent of what a business executive’s salary was at the time, so he had plenty of money to do whatever he wanted to do and to say whatever he wanted to say. In Ellington he took on one of the most successful black businessmen/entertainers of the era, who earned his success in a completely segregated society. Hammond was criticizing Ellington essentially for not taking a stand for other blacks, or for providing opportunites for them. While Hammond’s motive was to expand opportunity for other black musicians, his method for doing this — through criticizing Duke Ellington — was appalling. There is no other way to explain this than to say that was John Hammond, and that was the way he conducted his business. It wasn’t always pretty.

JJM There is no question he is a controversial figure who often twisted facts to make a point. In one instance, he fabricated a tour of England that was to include a number of well-known white and black musicians — Benny Carter, Teddy Wilson, and Gene Krupa among them — and when the tour didn’t happen, he falsely blamed an English promoter by the name of Jack Hylton for its failure. How could he get away with this?

DP Probably because he had a lot of money and because he was a prolific, good writer, so when the editors at Downbeat discovered that the tour was a farce, they just basically overlooked it and told him to write about something else. I don’t think anybody took it all that seriously, and everybody just went about his or her business.

JJM Sure, but why would he make this tour up in the first place? It is as if he just wanted to bring all this attention to himself without regard for his or Hylton’s reputation.

DP Absolutely. He wanted to pretend that he was in a position to make this integrated tour happen. Again, it is a case of method versus motive. Who was going to make a mixed race tour of this magnitude happen? Who would arrange to have all the players change their schedules in order to participate? Who would get the visas? The logistics of it were unthinkable, but here is John Hammond, pretending it is going to happen, writing about it and promoting it, and then the whole thing falls apart — although it really couldn’t fall apart since it never existed in the first place!

JJM He had an incredible eye for talent, was a great promoter, and a good writer, but he was a lousy reporter.

DP He wasn’t a reporter

JJM Well, he certainly reported things as fact. For example, he reported the false circumstances of Bessie Smith’s death as fact in Downbeat, and continued to do so even years later

DP If he was a great guy from start to finish, he’d be uninteresting and I wouldn’t have written about him. These kinds of stunts were attempts to further his own agenda. In the case of Bessie Smith’s death, he didn’t like facts getting in the way of a good story. From what I understand, some black musicians with their own agendas told Hammond that she died because she was not admitted to a white hospital. As you say, a good reporter would go out and find out if that really happened, but instead, he decided not to do that — he took their word for it and wrote about it. The question is why didn’t he change his tune about the story decades later, after Smith’s biographer Chris Albertson clearly proved it to be wrong? Why didn’t he admit the story was a lie? It’s because he was Hammond and he had a lot of money and he wasn’t going to back down from what he originally wrote. He felt that it was more important to get this false story out there to raise awareness of a social injustice in the South rather than tell the truth, which was far more boring.

JJM Sure, but he could have raised awareness without fabricating a story like this, and surely his life would have still been interesting …

DP I work in journalism, and this kind of thing still goes on today. He added a little spice to the story, which he was completely capable of doing.

JJM You write about Hammond’s influence on Count Basie, which obviously was really important. Chuck Haddix, who wrote a history of jazz in Kansas City, believes that Hammond would not have known about Basie had it not been for local Downbeat writer Dave Dexter goading him into coming to Kansas City.

DP Yes, Haddix told me that story too, but I don’t believe it. Hammond heard Count Basie on the radio and went out there. If he met Dave Dexter while he was out there, then that’s fine.

JJM What were Hammond’s ideas for Basie’s band, and why was Basie receptive to them?

DP Basie saw what Hammond could do after setting up dates for him in Chicago, where he made the kind of money he never dreamed possible before meeting him. He then took him to New York, where he played in the city’s biggest ballrooms, as well as getting him recording dates. Basie developed a level of trust for Hammond as a result. Perhaps an argument can be made that he pushed the relationship too far by replacing some of the musicians in the band, which engendered some bad feelings for him. The most significant replacement was of the guitarist Claude Williams, whose place in the band was taken by Freddie Green. Green was a New York player who Hammond used to see play at a club in the Village called The Black Cat. There’s a great story about Hammond bringing Basie, Goodman, and Lester Young to this club one night to meet Green, and they all started jamming together. A week later, Green joined the band, went on tour with them, and stayed for fifty years, becoming arguably one of the greatest rhythm guitarists in the history of jazz. Again, perhaps Hammond’s methods were not the best — he was a heavy-handed guy who felt that when he was right, he did what needed to be done. No one can argue with his results, though.

JJM In 1938, Hammond produced the “Spirituals to Swing” concert performed in Carnegie Hall, which to this day is considered to be one of the most ambitious and creatively conceived concerts ever. What was his vision for this concert?

DP Hammond believed that a lot of popular music in America during that time — especially swing jazz, which was arguably the most popular music at the time had its roots in African American culture, going all the way back to the African rhythms that were brought here, and to the slave chants that evolved out of that. Little by little, this turned into the Delta jazz and Delta blues, and into the jazz that came from New Orleans. He felt that the highest evolution of that music was the Basie band, and he wanted to create a show that displayed the music’s evolution to a well-heeled white audience in New York City. He went down south with Goddard Lieberson — who later ran Columbia Records — and together they found eight or nine acts there and brought them to Carnegie Hall to perform in the concert and help display the evolution of American music from African Rhythms, to field chants, to spirituals, to Gospel, to Dixieland jazz, to the Kansas City sound of Basie’s band. The concert was a huge success, and the CD remains one of the finest collections of music a jazz fan could own.

JJM It is interesting that Hammond didn’t get involved in the bebop period following World War II. Why was his influence on bebop so minimal, especially given what you describe as “the rebellion inherent in the music,” a characteristic seemingly well-suited to Hammond?

DP There are different trains of thought on that. Hammond felt the music was unnecessarily challenging and therefore pretentious, and he stuck by that. Conversely, the school of thought is that the people who were making that music — the Charlie Parker’s, the Thelonious Monk’s, the Charlie Christian’s — were the kinds of personalities unlikely to allow themselves to be led around by the nose by a guy like John Hammond. That’s the point often made, that even if Hammond had wanted to participate in bebop in a fashion suitable to his liking, the musicians wouldn’t let him — the door was locked. And, since he claimed that the music was pretentious, they didn’t want to have anything to do with him anyway.

JJM Why did he feel bebop was pretentious?

DP He thought that the music was written by a small group of jazz musicians solely for a small group of jazz musicians. Hammond liked his music to be inclusive — he wanted everyone to hear Benny Goodman, Charlie Christian, and Lionel Hampton — he didn’t want only fifteen people to appreciate the music that was being performed. He felt in some cases the thought processes around the making of early bebop was to preclude rather than include.

JJM So he was uncomfortable that bebop was not a popular music — not something large groups of people could dance to.

DP Very much so. The music didn’t swing.

JJM By the mid-fifties, you wrote that Hammond had a reason to feel older. “The music landscape had changed dramatically in the ten years since he had been released from the Army. Benny Goodman, Teddy Wilson, and Count Basie, Hammond proteges and stalwarts of the swing era, were now regarded more as legends than as vibrant contributors to the contemporary scene. Hammond’s reputation had similarly faded over time.” How was he determined to change his reputation?

DP I don’t know whether or not he was determined to change his reputation. He spent about ten years in the quasi-jazz wilderness of Vanguard Records, which was a very small, independent label that had really earned its chops as a classical label. Hammond was hired to build up their jazz library, which is what he did for most of the fifties. He recorded musicians like Mel Powell, Ruby Braff and Buck Clayton, whose music was a mix of the swing he was producing in the thirties and the bebop that was popular in the fifties. It is akin to the chamber jazz that he made with the Goodman Trio and the Goodman Quartet, that sort of stuff. Nice recordings that were basically done well under the radar.

In 1959, his friend Goddard Lieberson — who was running Columbia Records — called and asked Hammond to go to work for him. He agreed, and it was at this point that he made the leap from jazz to folk, and the first artist he signed to Columbia was Pete Seeger, who couldn’t have been further away from the jazz music he had been a part of during the first thirty years of his career. Though Seeger was not a jazz musician, he represented the kind artist Hammond had always worked with — he was a great musician whose music possessed a social message. And, on top of that, he had a feeling that Seeger would sell a lot of records for Columbia, which he did. In addition, Seeger’s presence on Columbia opened the door for Hammond’s third signing for Columbia, which was Bob Dylan. People often ask me how Hammond had this ability to find these genius artists, and I can’t answer that other than to say that he just knew.

JJM Yes, and whether he was able to plot the signings or not, it is possible that without Seeger on the label, Dylan wouldn’t have signed with Columbia.

DP There are so many stories about Dylan. I was fortunate to interview Harold Leventhal, who was the guy young folk musicians in New York City consulted at the time, and he told me that Dylan signed with Columbia because Seeger was there, and that he heard Seeger was given free rein to do what he wanted to do.

JJM Concerning the signing, Dylan wrote, “John Hammond put a contract down in front of me — the standard one they give to any new artist. He said, ‘Do you know what this is?’ I looked at the top of the page which said Columbia Records, and I said, ‘Where do I sign?’ Hammond showed me where and I wrote my name down with a steady hand. I trusted him. Who wouldn’t? There were maybe a thousand kings in the world and he was one of them.”

DP That’s right. Dylan did me a big favor. He wouldn’t speak to me in person but he published his memoir right around the time that I was finishing up my book. Dylan is not one to flatter an awful lot of people, let alone people who helped him in his career along the way, but he made that unbelievably flattering reference to Hammond near the end of his book. He also wrote about how much of an influence he had over him, and how he gave him unreleased recordings of Robert Johnson because Hammond felt he was the “real deal.” Dylan claims to have carried these all over Greenwich Village with him.

JJM Did Hammond immediately recognize that Dylan’s music could be the catalyst for social change?

DP I think saying that he recognized that ability in Dylan immediately would be overstating things. In Dylan, Hammond saw a rare combination of many things, in particular an almost provocative charisma he witnessed during his live performances. He also saw that Dylan was taking risks few other performers were willing to; for example, putting in twists to popular songs other artists were performing basically note for note. Hammond was intrigued by that. Could he have predicted in 1961 that Dylan would rewrite the rules to popular music? Hardly. But was he surprised when he did? No.

JJM He didn’t have much support at Columbia for Dylan, who was referred to in-house as “Hammond’s folly.”

DP That was early on. Hammond was an old friend of Lieberson’s, so he had a lot more rope, and because he wasn’t shy, he had no qualms about going directly to the top and asking for he what he wanted. Naturally, that engendered some resentment on the part of some of the other A&R guys he was working with. Hammond loudly promoted Dylan at Columbia and made it clear that the label should keep him, even after his first album did not sell well.

Dylan proved to be a pretty savvy young man, having hired Albert Grossman — one of the more notorious figures in rock and roll — as his manager. He insisted that Hammond and Columbia renegotiate his entire original contract, claiming it to be void after the release of his first album. Hammond had to sell the idea of renegotiating Dylan’s contract to his superiors, who saw nothing remarkable about him and questioned the wisdom of giving him more money. In fact, they were not even sure they wanted to put another album of his out, and discussed releasing him from the label. To this, Hammond basically said, “Over my dead body.” He told them Dylan was powerful and he needed more time to develop and become the artist he can become — which is what Hammond said about many of his artists. Luckily for Hammond, at some point during this period Dylan wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which quieted everyone’s concerns about whether he was going to have a lasting impact, not only as a songwriter but also as someone who could make money for Columbia. This is another example of Hammond’s ability to spot artists who would not only appeal to a broad number of people in an aesthetic way and commercial way. That is what happened with Dylan, and “Blowin’ in the Wind” was the turning point for “Hammond’s Folly.”

JJM How did he get connected with Bruce Springsteen?

DP By the time Springsteen came along, Hammond was a living legend and artists wanted to get their tapes to him, hoping to be the next Bob Dylan, Billie Holiday, Leonard Cohen, or whoever. Springsteen’s manager and producer at the time, Mike Appel, was somehow able to convince Hammond’s secretary to tell him he should see this twenty-two-year-old rock n’ roller from New Jersey perform. He was armed with no more than an acoustic guitar, but after three songs, Hammond very famously informed Springsteen that he had to be on Columbia Records. Again, I can’t begin to quantify how Hammond was able to see this kind of talent. One explanation is that Hammond touted hundreds of artists over the years who did not turn into the next Bruce Springsteen; along with the dozen or so we are familiar with, there were many dozens more who didn’t get past the demo stage or may have only had a minor hit. But his track record for turning unproven quantities into icons is unmatched.

JJM Given Hammond’s sensibilities, how did he deal with the artists who, despite his interest and involvement in their careers, experienced failure?

DP I interviewed several people like that and they all spoke about his enthusiasm for their work, but then the phone would ring and he would say it’s not going to work out, that he couldn’t get them past the demo stage. He would remain committed to them but pass the buck, saying he couldn’t convince the “suits” at Columbia to move the project beyond the demo stage. These people all took Hammond at his word and were still very grateful for the enthusiasm and the passion that Hammond had put into their work. Were they bitter that they didn’t become the next Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen? Not really. Those who I spoke with were all thrilled by the fact they had been brought under the Hammond umbrella.

JJM You wrote about one of these players, Roy Gaines, a blues guitarist who landed on his feet and ended up having a nice career

DP He sure did. When George Benson was down, Hammond offered to lend him money of his own, and he called clubs up and down the East coast, he called music writers — whoever it may have been to help get him work.

JJM There is a perception that he could spot raw talent, but he didn’t know what to do with it in the studios.

DP I would say that is an accurate perception.

JJM According to Columbia producer Robert Altshuler, “ although he had these incredible ears and the ability to recognize talent at its earliest stage, at its embryotic stage, he was not very good at producing.”

DP Ahmet Ertegen, the founder of Atlantic Records, may have had the best explanation for this. He told me that the artists Hammond touted early in his career — Goodman, Teddy Wilson, Gene Krupa and Benny Carter among them — were virtuoso musicians and confident professionals who didn’t need to be “produced.” They knew what they were doing, and Hammond’s job was merely to bring these people together and get them in the studio, and while they played, he would read the New York Times off in the corner. Later on, it was his idea to do the same thing with artists like Dylan, Springsteen, and Leonard Cohen. He put them on a stool, hung the microphone over their head and had them sing their songs, but none of them wanted to do that. They were much more ambitious than that. They all wanted a bigger sound, and they wanted opportunities to do different things, and when they began to express this, it clashed with Hammond ‘s approach. In that sense, at least, their professional relationship would end, and he had a pattern of that. The personal relationships didn’t end — Hammond remained friends with most of the musicians he worked with — but he was an old school producer. He was not someone who fiddled with dials and created a Phil Spector-like sound. That was not Hammond’s role as a producer.

JJM He was not into new technology …

DP No, he saw it as gimmickry. He felt technology was for those who weren’t talented enough to make real music of their own.

JJM How do you measure his influence on our culture?

DP His influence is huge. My wife and I will sometimes move up and down the radio dial and try to find a song performed by someone who was connected to Hammond, and it never takes us more than a few minutes. Look at all the artists whose career he influenced: Aretha Franklin can be found on the oldies station; ten years ago, Dylan was seen as an over-the-hill flake, but he is now arguably the preeminent icon of pop of the Baby Boomer generation; Springsteen is more popular than ever, having just been part of an album of songs made famous by Pete Seeger, who was another Hammond guy! I would argue that someone like Billie Holiday is more popular now than she was when she was alive, and, when asked about their influences, people like Nora Jones and Diana Krall will list Billie Holiday. His influence is as broad as the American landscape.

There were so many variables to John Hammond’s life. If he had been all good, he would have been boring to write about, and if he had been all bad, I surely wouldn’t have chosen to spend five years of my live with a despicable guy. If he had just been influential in the jazz world, I wouldn’t have wanted to write this book, nor if it had just been folk or rock and roll. But, Hammond had his fingers on many different pulses — not just the pulse.

.

.

“Was it merely a coincidence that the same man provided the springboard for such a diverse and lasting array of talent? Hardly. Time and again Hammond proved eerily prescient in his awareness of seismic change that loomed ahead for American society, and in how that change would manifest itself through popular culture, in particular through music. He seemed to know what America wanted to hear before America knew it.”

– Dunstan Prial

The Producer:

John Hammond and the Soul of American Music

by

Dunstan Prial

.

.

___

.

.

About Dunstan Prial

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

DP Paul Newman.

JJM Why?

DP Hud. Cool Hand Luke. Do I need any other explanation? Those characters are the iconoclastic anti-heroes. I like that sort of stuff.

.

.

___

.

.

Dunstan Prial, born in New Jersey in 1970, has worked as a reporter with the Associated Press, and was led to Hammond’s career by his admiration for Bruce Springsteen. He lives in Bristol, Rhode Island.

.

.

This interview took place on November 20, 2006, and was hosted and produced by Jerry Jazz Musician editor/publisher Joe Maita

.

# Text from the publisher

.

.

___

.

.

.

Click here to read other interviews published on Jerry Jazz Musician

Click here to subscribe to the (free) Jerry Jazz Musician quarterly newsletter

Click here to help support the ongoing publication of Jerry Jazz Musician, and to keep it commercial-free (thank you!)

.

___

.

.

Jerry Jazz Musician…human produced (and AI-free) since 1999

.

.

.