.

.

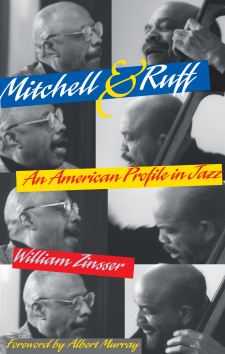

Mitchell and Ruff:

An American Profile in Jazz

by

William Zinsser

.

Since 1955, Dwike Mitchell and Willie Ruff have been performing, teaching, and sharing jazz with the country and the world. William Zinsser, best-selling author of On Writing Well, follows the duo to China, to the American Midwest, to New York City, and to Venice (where Ruff travels back to the roots of Western music in order to explore jazz’s heritage).

Zinsser tells how these two men, raised in small towns in the South in the 1930s and 40s, struggled and persevered to become masters of their craft–and how they came to embrace the tradition of jazz as it is handed down from one generation to the next.

The New York Times called it “satisfyingly unusual.”

“It’s a revelation,” said Studs Terkel.

In an interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, Zinsser discusses his special friendship with Mitchell and Ruff, their background, and the incredible journeys he accompanied them on throughout the world.

.

.

_____

.

.

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

WZ Everybody on the New York Giants during the early 1930’s. Mel Ott, Bill Terry, Carl Hubbell were among them. My other first heroes were the sportswriters, mainly the baseball writers for the New York Herald-Tribune and the New York Times. Also, the New York Sun, a paper that was obsessed with baseball.

JJM Did these writers inspire you to want to become a writer yourself?

WZ Yes, to become a newspaper man.

JJM Is that part of your background?

WZ Yes. I served in WWII overseas, and the paper I always wanted to grow up to work on was the New York Herald-Tribune. I got a job on that paper as soon as I got home from the war. The first 13 years of my life were spent on that paper, as a writer, and as an editor. I spent ten years as a drama editor and as a movie critic there. So, I have a journalistic background.

JJM When you say you were the drama and music critic of the Herald-Tribune, what is your first significant memory witnessing a jazz event in New York, or anywhere around the world?

WZ I am not a “jazz” person, per se. I am a “show tune” person. Besides baseball, my other passion in life has been American popular songs, specifically those written between Showboat in 1927, and the rise of rock in the 1960’s, which is a 40 year “golden age”. My parents used to go to Broadway shows, and bring home the sheet music which was sold in the lobby of the theatre, and play them on the piano. At a very early age, I became addicted to the songs of Harold Arlen, Cole Porter, the Gershwin’s and I had the good luck to be born with a musical ear, so I have always been able to play whatever songs I heard. I play them quite a lot around New York now as a pianist in clubs. I play standards, and I know thousands of them, have known them since I was a small boy. I have never been a particular jazz fan, but of course, all these standards I play are standard repertoire for jazz musicians, singers and cabaret artists. Sinatra sang almost nothing other than standards for six decades.

So, despite having written this book on two jazz musicians, I am not a person who knows an awful lot about the great jazz heroes. My interest has always been in jazz musicians who were story tellers, like Ella Fitzgerald, who would sing the lyric and tell the story.

JJM And they sing these standards that you love so much…

WZ Yes. In the 1970’s I spent at Yale as a teacher of writing. I was also Master of Branford College, a residential college of Yale. One of the faculty members I worked with at Branford was Willie Ruff, a great french horn player, who was also a member of the Yale School of Music at the time.

Willie Ruff was able to persuade the president of Yale University to establish a Duke Ellington fellowship, whereby many of the great jazz musicians of the era would become “Ellington Fellows” at Yale. The unspoken arrangement was that these great musicians would come back to Yale periodically to teach. When they came, Willie would trot them out into the local high schools, almost entirely African-American attended schools. Thus, he would take people like Dizzy Gillespie out into the high schools to speak. At the time, the 1960’s, young African-Americans really had no knowledge of the great tradition of their ancestors as jazz musicians because rock and roll had displaced jazz as the music of the country, and also, blacks at that time were rarely seen on prime time television. Willie believed it was important that the story be told. The kids responded to these visiting musicians in a very positive way.

I lived with Willie Ruff in Branford College and he and I put on many musical shows together there. Every time he invited one of these great musicians to come to Yale, he also invited his long-time pianist Dwike Mitchell. I played the piano all my life, and I played it well, but I think anyone knows when his “teacher” comes along, and the sound that Dwike Mitchell created on the piano was exactly the sound that I aspired to play myself. It was a cranking up of my own harmonic sensibility to a higher level. His taste was impeccable, his harmonies were awesome, his technique was astounding – but the main thing was that he was always perfectly in tuned to the heritage of the person he was accompanying, whether it was Dizzy, the tap dancer Honey Coles, or whoever…Any time this man came from New York to play in New Haven, I would go up and listen to him play. I would take any opportunity to listen to him play. When I moved back to New York in 1970, I asked him if he would take on a new piano student, and he said “sure. I went to his house once a week for the next 20 years.

I got to know him extremely well, and we talked about many things besides music. I learned more than what it was like to be just a piano player but also an artist. The sensibility of this man as an artist quickly took me over and my Saturday morning lessons were the high point of my week. It greatly expanded my life, and of course it made me a much better player.

I began to wonder about Mitchell and Ruff in terms of where they came from, and I thought it would be fun to write about their childhood. It was about that time that Mitchell told me Willie Ruff was taking lessons in mandarin at Yale, which was the eighth language he had taught himself, and that he now felt fluent enough to go to China. He wanted Mitchell to go with him and the two of them would introduce jazz at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. I asked if I could go along and they allowed me to do so. This trip is described in the first chapter of the book, and the last chapter of the book is my going to Venice with Willie Ruff when he played Gregorian Chants on the french horn at St. Mark’s cathedral at night, when there were only three of us in the church. He wanted to get back in touch with the Venetian school of music that Paul Hindemith had put into his mind when he went to Yale to study music as a kid.

These two chapters became the exotic bookends for this book, “Mitchell and Ruff: An American Profile in Jazz”. But what was more important to me at that point was to tell a story of who they were. So I went down to Sheffield, Alabama, where Willie Ruff grew up, and to Dunedin, Florida, where Dwike Mitchell grew up. I was really blown away by the fact that these two men’s lives, both coming from poor families, who had no opportunities at all, were repeatedly crossed by someone who taught them what they needed to know. That seems almost miraculous, except I believe in those miracles.

What became important to me was to tell their stories, first separately through their childhoods, and then going into the Army, where they met at this remarkable Air Force base outside Columbus, Ohio, Lockborne Air Base, which is a conservatory, really, for great black musicians.

JJM In that chapter what was interesting to me was the luck Willie Ruff had there…He taught himself french horn after he was displaced as the band’s drummer.

WZ This is an amazing thing that he did…

JJM They created so many opportunities for themselves. They didn’t allow themselves to be victims of segregation.

WZ Absolutely. So, what I was really trying to do in writing this book was simply to tell their stories. It is a book filled with wonderful stories that I elicited from them and the other people. I am not trying in the book to make impassioned stories myself, I am trying to tell the stories as cleanly as well as I can, and let the readers say, “Isn’t that amazing!”

I think it is a very American book, a very life affirming book. It’s a book, to me, about possibilities in America, how these two people, who started with nothing, have taught themselves. What made me want to write a book about them is that they seemed to have a teaching bent themselves, as if having been the beneficiaries, when they were young, of so many people taking an interest in them. They in turn passed that along themselves, not only as Willie teaching at Yale, but most of the gigs they have done have been at colleges, especially at poor black colleges, where they not only play, but talk a little about jazz.

JJM To me, it was clear that they believed that their work can make the difference in the quality of the lives they touch. That’s a major theme of the book to me. Their lives crossed quite a bit…

WZ They first played together when Willie was 15 and Dwike was 17. They have played together ever since. I heard them in New York just last week (February, 2001) at the Yale Club. They are the oldest continuing group in jazz without personnel changes! They have been playing together since 1948 or so.

JJM Dwike Mitchell played with Lionel Hampton?

WZ Yes. Following the Army, he played with him for two years. Hampton, as the story goes, came with his band to the Lockborne Air Base and heard Mitchell, this “kid”, playing the piano there, and said “I want you as my pianist!” Hampton was so impressed by Mitchell, that he told him to call him when he got out of the Army. Mitchell instead went to study at a classical conservatory in Philadelphia for a couple of years and got himself a classical education. But then one day he was in a town in Florida, and he went to a Hampton concert in Jacksonville. Following the concert, he went up to Hampton with great shyness, and immediately Hampton told him he wanted him in the band. Hampton made room for him immediately. Mitchell joined the group two weeks later and toured with him for two years, all over the world. Hampton taught Mitchell how to pace a concert, how to gauge the audience, and a lot about travel and getting along in life.

JJM Tell me about this Venice trip you took with Willie Ruff. When he was attempting to get permission to play in St. Mark’s Cathedral, he had a couple bumps in the road, and at that time the two of you went out to visit the grave of Stravinsky, where he pulled out his french horn and played there…

WZ Yes. That chapter describes why Stravinsky is such a god to jazz musicians, especially to bebop musicians. He was playing what the bop musicians then called “weird” or “far out” music. He was rebuffed at first to play in the church, and then one day he remembered that Stravinsky was buried there. We went out to this island, which is Venice’s cemetery, and played an ancient Gregorian Chant for Stravinsky. It was deeply moving.

That Venice trip had so many interesting connections. The fact that the ancient Catholic Church’s music is almost identical to black Negro spiritual music. It has the same basis…the fact that Stravinsky is buried in Venice.

Willie Ruff has given me two of the most emotional moments of my life. In the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, when Dwike Mitchell improvised on the theme of a Chinese boy playing the piano, thereby proving to the Chinese, who don’t even have a word for improvisation, that jazz is a point of departure no matter what the tradition. So, music that day was the bridge between worlds totally opposite; east and west, oral and written, black and Asian. When Willie Ruff said to a Chinese student, “Come up here and play some music, and we will make a piece based on that”, and they did, that just totally blew the Chinese away. Everything they do musically is written down. To be in the room with that many antithesis at play was incredibly moving, and to have music transcend all those differences was something that Willie Ruff brought about by getting us there, and that Mitchell brought about by doing the improvisation.

Being in Venice with Ruff that night he was playing at St. Mark’s was the other emotional high point of my life. St. Mark’s is a cathedral that hosts 25,000 tourists a day, and that night there was nobody there but me, the sacristan, and Willie Ruff playing on the french horn – these ancient chants that have been part of the liturgy of that church since 1026. Inevitably, it was one of the most moving events of my life. There is something very emotional when you feel as if you are made part of a tradition that is unimaginably old, rich and complex. He is the single most interesting man I have ever known. Every time I see him he is doing something new and different.

JJM This is a deeply spirited book. We see lots of interesting books on jazz come through this office, all wonderful in their own way, but this is a unique book because it washes over the unnecessary. It doesn’t deal in meaningless facts, but instead deals in benchmarks in people’s lives whose philosophy is enriching those they leave behind.

WZ Albert Murray wrote the foreword to this book and he makes the point that what I was trying to find out is how an aesthetic sensibility is formed in this country, and that the book has nothing to do with social issues. It is a book trying to get two lives down in narrative form.

JJM Yes, in the foreword of the book, Murray wrote that the book’s fundamental concern is with the development of an American aesthetic sensibility, of how an American personality develops. “The book is an excellent natural history and in the development of our sensibility as indiginous American artists”. That’s one hell of a compliment, and I think that it’s truly the theme of the book.

WZ I do too. The book would not have succeeded if I had not really just set out to write this story. I am not in the book except as a guide. I am letting the people who are involved in the book tell the story.

JJM You are now writing a book called Easy to Remember. Tell me a little about that?

WZ The book is about the great American songwriters and their songs. Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein and Showboat, and goes up through the great songwriters of forty years later. The book tells their stories mainly through the lives of these songwriters – not only the composers but the lyricists – people like Dorothy Fields, Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Jules Stein, Frank Lesser, Steven Sondheim. It is really a story of my lifelong love affair with these songs. I describe who the men and women were who wrote the lyrics, and what shows, films or musicals they wrote the songs for, and what makes the song so good. I know the songs very well as a player and I know all the lyrics. I got hooked on these songs when I was a small boy, and have been playing them on the piano all my life. These songs are important to me, but also to many other people, because they are very rich in their associations. When I play these songs, people come up to me and recall their own experiences with them. When a pianist signs up to play these songs, you do more than just play them. I can see people’s faces change, their cares and worries drop away when these songs are played, because they are carried back to times that have warm and happy associations.

JJM I believe that our culture today is “melody starved”. I think that today’s pop music is more “message” rather than “melody” oriented. Easy to Remember may help remind us of the importance of melody in our lives…

WZ That is very true!

.

.

_____

.

.

Mitchell and Ruff:

An American Profile in Jazz

by

William Zinsser

.

.

.

Thank you for sharing this interview. William Zinsser is a person and a writer I admire.