.

.

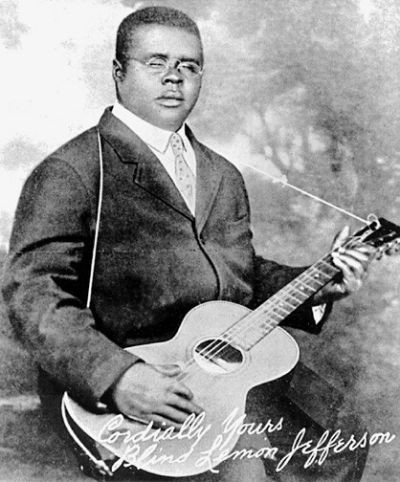

“Ways to Look at Blind Lemon Jefferson” a story by Larry Smith, was a short-listed entry in our recently concluded 57th Short Fiction Contest. It is published with the permission of the author.

.

.

_____

.

.

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Blind Lemon Jefferson, c. 1926

.

___

.

Ways to Look at Blind Lemon Jefferson

by Larry Smith

.

…..One of the best things about my life is that in the course of it I had the chance to see the great Blind Lemon Jefferson on eleven different occasions. This was especially gratifying because for me he was the finest blues singer who ever lived, even better than Robert Johnson or Charlie Patton or Bessie Smith.

….. But there was something else too. Each time I saw him he seemed a little different, his face somehow a different shape, the very style in which he carried his body–the way his legs moved, or the way his haunch sat on his thighs–very different from the time before. It was extremely mysterious.

….. And I’m not lying when I tell you that on more than a few of those eleven occasions there was tremendous and sometimes wonderful drama going on all around him. For example, the first time I saw him, it was right in the middle of a flood. I was working for a Memphis meat packer, driving a truck and heading toward the river from the east, my final destination Houston. It was about three in the morning when the banks overflowed. I was sitting in a diner at the time. There was no one there, just me and the cook and a waitress when suddenly we heard distant shouts that hung strangely in the pouring rain. There seemed to be many men calling to each other in voices that were desperate and tired.

….. I put my hood over my head and ran in the direction of the hubbub. I found it only a few hundred yards down the road. There were ten or twelve men there, all coloreds, along with a few women in stiff raincoats that nearly disguised what sex they were. They kept humping sandbags on top a feeble-looking stone water breaker. Someone had driven truckloads of bags over on Route 1 to the river. These people had been through this before; they had known, from the very first thunderclap, that a storm was coming, and probably a flood. There was plenty of material here to stanch the deluge but hardly enough hands to pile it high enough to do much good.

….. We worked past dawn and around seven were joined by another half-dozen men, but there wasn’t much we could do. Though we were able to stop the water pouring across the road for some yards on either side of us, there were huge accumulations of mud built up, I’d guess, from a hundred past floods, further down on the south end of the road. The water pummeled these heaps at their base, slowly at first, but before we could shift our positions the hard undertow dislodged the mounds and more water swirled our way, dark and steady. It wouldn’t have done any good to stand fast. I heard the men say the best thing to do was to fall back to the town behind us and try to barricade the stores and houses over there if things got really bad.

….. I ran for my truck at the diner. The water was to the door but I was able to hop in and drive to dry ground. I kept backing up as the water lapped at my tires. By nine I got to a hillock and barreled to the top. I had never seen an actual Mississippi flood before. I had only heard about one from an uncle of mine who was raised in Church Hill, and, to tell the truth, I was willing to endanger my truck and its cargo for a good vantage point.

….. By ten that morning the water was pouring in torrents at the foot of the hillock. I sat in the truck and watched scraps of roofs and pieces of furniture swim by a half-mile further down. I saw a dead dog or two. Then there was a boat. A couple of cops were riding in it, apparently out to survey the situation. In another twenty minutes a smaller row boat came by. At first I just saw the rower, a young black in a torn t-shirt and blue jeans working furiously to keep abreast of the flow.

….. Sitting behind him in the boat was Blind Lemon Jefferson. I knew it was him. I knew it instinctively. He was impassive. His arms were folded. He seemed to be completely balanced in the boat and confident that it would reach safety. He was dressed in a dark brown vest and tweedy gray pants. I was astonished. Where had he come from and why was he hazarding the storm? Had it not been possible for him to fall back to dry ground? He didn’t twitch, his torso remained immobile as the turbulent water whipped around and under him. The oarsman was sweating and looked scared. As the boat rode past, I kept my eye on its illustrious passenger and never saw him flinch or bob or sway until the vessel was out of sight and it wasn’t even a speck on the darksome horizon. Then there was more lightning and the rain fell sideways and blew against my window like wind on an open plain.

….. I was eighteen at the time. I finished my run to Houston and the foreman there–it was a company my Memphis man’s brother owned part of–said, “Boy, you got a job here anytime.” And I was very tempted to move my whole life to Houston because there was a girl there named Louise who was the first girl I had had. She was a very good girl, and I loved her. But I finally decided to go home first and see my Mom in Selma, where I’m from.

….. The first Thursday after I got home Mama said to me, “Son, there’s someone here you have to talk to.”

….. I didn’t know how my mother knew this man, and, although his manner to me was kindly from the start, I can’t say I liked him much. He had a way of staring at me like I was a mysterious brand of bug and that I had a way of crawling he’d never seen before.

….. “You don’t know me, do you?” he asked.

….. “No sir, I don’t think I do.”

….. “I’m Reverend Davenport from the Lutheran Church in Perryville, and I’ve been lookin’ at you for many years now.”

….. “Yes sir.”

….. “I’m sure you like to do your Christian duty,” he said, and I nodded. “Well I like to do mine too,” he said. I was a little nervous and glanced at Mama, who was sitting in the stiff brown chair with her hands folded on the red-striped green apron that always felt so warm and full of talcum. She smiled as if to say it was okay. The Reverend Davenport was a strange one, no doubt about that, but he’d do me no harm at all. “Spell `irritation,'” he said.

….. “I-R-R-I-T-A-T-I-O-N.”

….. “I’ve never known a colored could spell like that,” he said. “You didn’t even have to think twice about it, did you? Now tell me, who invented electricity and the kite?”

….. “Benjamin Franklin.”

….. “My goodness! Boy, I want to see to it that you go to Alabama Lutheran. Would you like that?”

….. “Thank you, sir.”

….. “One thing. Don’t ever tell nobody that you’re colored. No one can see. You sure look white to me and, if you act white, I’ll handle the rest.”

….. It was just behind the school one day during the middle of my second year at Alabama Lutheran, which is a junior college in Selma. He was over by the road, in the shade of a clump of trees. Blind Lemon Jefferson was sitting quietly by himself when a few of the students gave him a quarter and asked him to sing. His face was heavier than I remembered it, and his body was poised beside the elm tree like a stone wall. His eyelids were heavy. He nodded without smiling when the students asked him, and he sang a few verses of “Eagle Eyed Mama.” Then he fell silent and the students chuckled in appreciation, nice folks, but not knowing who this man really was. As they started to walk away I saw Lemon’s squat body lurch spastically forward. “Where am I?” he called out, to no one in particular. I didn’t answer. I backed away and went off to class.

….. I was back in Houston visiting Louise the next time. By then Lemon’s famous friendship with Leadbelly had already matured. Everyone knows the story of how the two men had met on a train, had argued over something, and then drew knives. I assume Leadbelly had been impressed, almost amused in an admiring sort of way, despite the danger, by the blind man’s prowess: the deftness with which he pulled the knife, the nimbleness with which he wielded it, and his extraordinary ability to sense and smell his opponent’s presence and movement. No doubt singing wasn’t the only talent by which Lemon made up for being blind. I have to admit, there’s something about blind folks that spooks me. They seem to be totally helpless and yet at the same time able to do and know much greater things than the rest of us. I want to pick them up in my arms and save them from the world, but were I to do so I’d be afraid of what might be going on inside their heads all the while.

….. It was at an integrated bar called the Chateau Mediterraneo. I say integrated, except the white men who hung out there were gamblers mainly. They were dangerous sorts for the most part but I kind of liked them because they were good to coloreds, maybe because they were outcasts themselves from other whites, even from other white gamblers. Lemon and Leadbelly were both there that night and you should have seen the way they were being treated. Folks were buying them drinks and the whites were joking with them and calling them “Sweet Lemon” and “Easy Mr. Huddie.” So Leadbelly got happy and decided he wanted to sing. “You want to sing, Lemon?” he asked.

….. “Naw, I don’t want to sing.”

….. Leadbelly started singing “New Iberia,” which he often did when he didn’t have his guitar handy. A tall fine lady, a black one, in a red dress with carnations at the bosom was loving it and sort of stood and swayed between where Leadbelly was singing and where Lemon was sitting and listening. As the song wound down Lemon reached out and grabbed the woman’s rear end with both his hands and wouldn’t let go.

….. “I got me one, Huddie, I got me one,” he called out, and the whole place laughed and the poor lady tried to smile. “I got me one, Huddie,” Lemon called out again, “I got me one.” I’ll always remember how Lemon’s whole head had fallen backward when he reached out his hands. He was wearing dark oval spectacles, small and distinguished, and, as his chin rose, I saw the flesh of his eyelids pointing upward like he was praying. Those lids were unmarked. They were smooth little black coverlets.

….. Of course Lemon was hell on women, which reminds me of a time in a black hotel in Bay City. I was driving meat again and pulled in on my way to Houston, dog-tired. I signed the register and chatted a bit with the clerk who was very friendly. “You know Blind Lemon Jefferson is here,” he said as I was starting away.

….. I turned back. “Staying here right now?”

….. “He came in with this little woman, and I mean little! She wasn’t no more than four foot four. And a nervous one too. She kept mumblin’, `What you gonna do to me? What you gonna do?’ Lemon signs in with his mark and asks me if I’ll take a song or two in place of money. `Hell,’ I said, `I can’t take no song.’ So he puts his hand on the woman’s tits and says, `Maybe you want a slice of this here.’ I didn’t answer him a word so he shrugged his shoulders and reached into his pocket for some cash.” The clerk smiled philosophically. “Stick around if you want. You’re bound to get a glimpse of him.”

….. I woke up at dawn in hopes of seeing him leave the hotel. How bright it was that morning! There were big drops of dew everywhere, floating in puddles, hanging from twigs and from the edges of the buildings. The sun streamed through so that there was a soft blue light everywhere. Into this magical brightness came Blind Lemon Jefferson and the little woman. He had a powerful stride on him that day like the fat on him was all muscle. And his neck was very stiff, so that his head seemed to be held up unnaturally high as if he were a king. The woman, on the other hand, looked even smaller than she was. God knows what they must have been doing that night but she scampered in front of him like a puppy dog and her eyes never left the ground.

….. The next three times I saw him were all in Chicago. I had gotten a job driving from the meat plants to the suburbs. I’d even go out to Cicero once in a while since I could still pass. Occasionally I’d do a route to Gary or Cleveland. I didn’t mind it. Where I was living you could hear some of the best singers who’d come up from Memphis or Mississippi or Texas. And I got to like jazz too, and I developed an appreciation for the way white men were learning to play it.

….. It was Paramount Records that brought Lemon up. He’d be on the South Side almost every night, particularly after a recording session. I saw him once at the Club Delight sitting with a woman that looked to me like a prostitute. At first I hardly noticed him. When I did his back was to me, then he whirled around toward the small stage close to my table when the singer came on. I didn’t know the singer, but remembering now I could swear it was a young Tampa Red. He was playing bottleneck and would punctuate it with dirty little runs on the kazoo. That night I saw something in Lemon I’d never forget. His face was concentrated yet softer than I might have expected as he sat back appreciating the music. Tampa Red and Lemon could have been alone for that hour, alone and somewhere else.

….. Then Louise came for a visit and we saw Lemon one day standing on Clark St. in the pouring rain. It was the first time Louise had ever seen him and she was surprised and amazed. He was a pathetic-looking creature hunched over, hatless, his lips moving slightly in the manner of the very old or insane. His pants were ragged, muddied at the cuffs, and his shirt collar brown and frayed. I was taken aback as well. But it was funny; I got over the surprise quickly and was left with a kind of shame instead, shame in front of Louise that this wretch was the great man of whom I had so often spoken. Louise was embarrassed, more for my sake than for Blind Lemon’s.

…..We stood sheltered beneath an apartment awning across the way, unsure what to do. His body was so bent I thought he’d soon be having a hump. Then an incredible thing happened. A big black limousine pulled up to the curb just a half block past Lemon. A white man stuck his head out the back window and called, “Hey man, come on.”

….. “I’m comin’,” Lemon called back. Without even straightening his back he scurried across the pavement and disappeared into the car.

….. Of course the big city is like that. You’re never sure what’s happening or why. Now in those days Houston was nothing like Chicago; in fact, it still isn’t. Every day in Chicago was full of things to remember. One evening, for example, Louise and I went to hear Lemon sing at a little bar in the forties on the South Side that was jammed with coloreds and students from the nearby university. That night Lemon was the very opposite of what we had seen on Clark St. There were broad shiny golden cloth bands sewn across his shirt and his whole body was moving around like a jellyfish. His face was all afire with pleasure. Then the place quieted down and Lemon sang “Big Night Blues.” Something strange happened to me when he got to the end. Everybody was leaning forward and listening and Lemon’s voice was so clear; I’d even say distant, in an odd way. He sang

Wild women like their whiskey

their gin and their rock `n rye

and it was as if no one in the joint, least of all Lemon himself, could really have been thinking or caring about wild women or liquor or anything of the kind. I sure don’t know what they were all thinking of, or what was going on in my own mind for that matter, but to this day whenever I think of dim lights and funky whores I’m filled with a deep tranquility that I can’t quite explain.

….. That was in the dead of a long and wearisome summer. By October I had saved up money and moved back to Houston. I figured with all the meat I’d been toting around in my life I’d might as well open a restaurant. Louise isn’t much of a cook, but I wasn’t planning on serving much else besides hamburgers and coffee. I figured it would be my friendly personality that would bring in the business.

….. One night after I closed up a driver who had known me as far back as Memphis came up to the door outside and started banging on the glass pane. He was smiling broadly, and when I unlocked he told me that Lemon had been spotted in a bar just off the main drag in Juliff. That was a hell of a drive at that hour so I rang up Louise and told her to go to bed and off I went. I got there about half past three and the bar was empty but it was still open. I ordered a beer and asked, “You know if Blind Lemon Jefferson’s been here in the last couple of hours?”

….. The bartender didn’t say a word and just pointed with his shoulder toward a side exit. Then he turned away. I drank down the beer and went out that door. It opened on an alley and, some fifty yards down, there was a naked woman. I saw her from the back. She was dancing very wildly and uttering no sound. In fact, the quiet was enormous. She was thin and her arms were long and they flew above her head like trains of flies. In another moment I saw him sitting there on the ground: Blind Lemon Jefferson, squat, meditative, his hands folded politely on his lap. His head was jerked forward toward the woman as if he had eyes to see. And what could she have been thinking, realizing that this man who was pretending to watch her dance was blind? Maybe she was only dancing to please herself. Or did she know, was she actually smart enough to know how intently Lemon could probably feel each hot grind just by sniffing the inches the sweat on her flesh was flying from left to right and back again? I tiptoed away and circled around to the main street where my car was parked. I stood there another moment or two listening for a howl or a laugh or a groan. But there was nothing.

….. The next time I saw him was, I suppose, miraculous. It was in the heart of Houston some months after that night in Juliff. I was in a bar frequented by musicians. Lemon came in that night on a woman’s arm and dressed to kill, a little like that time in Chicago but, instead of colorful threaded inlays, a big green jewel, maybe an emerald, was pinned to a strap across his shoulder. I had never seen him smiling so broadly. He and the woman sat a table or two away. Soon she started licking his face and rubbing big sexy circles across his chest with her hands. She finally let out her tongue like a bitch in heat. I couldn’t take my eyes off the scene. But before I knew it, the woman turned a half-circle and faced me. “What are you staring at, white man?” she snapped with contempt in her voice.

….. “He ain’t a white man,” said Blind Lemon Jefferson, the broad smile still glued on. “He just looks that way.”

.

….. A year later there was hard times everywhere as people lost all their money and their homes, although I myself didn’t wind up too bad; I still kept my restaurant. One day that summer I was driving to Austin to visit a friend of my mother’s. It was an empty road for miles to the northwest and the dry sky was empty blue as far as I could see. Halfway there I finally saw another car approaching from the opposite direction. At first it was a dot in the distance. Then I heard a faint rumble and soon I could make out the headlights. I remember I was humming something to myself as the vehicle got nearer, some ditty like “Give My Regards To Broadway.” I was going a good clip; so was the other car. We came within a few yards of each other and in that brief flash I saw Lemon sitting in the passenger seat, his head resting back on the seat, one of his arms pulled up in a lazy V. I remember only how bored he seemed in that instant. I never saw the driver.

….. It was the last time I saw him alive. There were all sorts of stories as to how he died. Some say a jealous husband gunned him down, and that he died like Robert Johnson, only Johnson was poisoned. Others say some cowboys traveling east didn’t like the look of him. I’ve even heard he put a gun to his own head. One guy says a jilted girlfriend mowed him over with a pickup truck. There’s one thing though that everyone’s in agreement on, and that’s that Lemon didn’t go from natural causes.

….. I took a drive to Wortham, where he had died, for a final farewell. It was very strange at first. I thought I had tumbled into a foreign country because no one there really knew who he was. The hell with it, I thought; I’ll pretend I’m white and just ask the police.

….. I flagged down a patrol car. “How are you?” I asked. “I’m with Paramount Records and I understand one of my niggers perished in these parts.”

….. “Sure, you mean Jefferson. Few months back.”

….. “How did it happen?”

….. “If it don’t concern us, we just tell `em to bury their dead and don’t be botherin’ the townspeople.”

…..“Where do they bury `em?”

….. “You’ll see a low ridge about two miles outside town past the traffic light. Just on top of that ridge there’s a patch of five hundred yards or so of dirt. He’s under there somewhere.”

….. “How many others would you say are under there with him?” I asked, out of curiosity.

…..“I know of about ten or fifteen, but that’s only since I’ve been working here. I came not long ago from Beaumont.”

….. It was a wonderful deep brown, that dirt. I walked over it thinking how Lemon was there, but no one could say exactly where. The wind kicked up a bit and the sky darkened. Bits of the soil were swirling at my feet. I had a pretty good idea as to who was buried there with him; I could tell you some of their life stories and be wrong only in the details. It’s always the same song we ask for, the same song over and over. And it kind of thrilled me to know that maybe no one else, not even his good friends like Leadbelly or Lightnin’ Hopkins, would find this mass grave of his or think to look. I can still smell the damp loam. I can conjure up its smell at will, and whenever I do it occurs to me that I was probably the last man who ever looked on Blind Lemon Jefferson.

.

.

___

.

.

Larry Smith’s story collections, A Shield of Paris and Floodlands were published in 2019 by Adelaide Books. His novella Patrick Fitzmike and Mike Fitzpatrick, was published in 2016 by Outpost 19. A Pushcart-nominated writer, Smith’s stories have appeared in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Serving House Journal, Sequestrum, Exquisite Corpse, The Collagist, and [PANK], among numerous others. His poetry has appeared in Descant (Canada) and Elimae, among others. Smith lives in New Jersey. Visit Larrysmithfiction.com.

.

.

Listen to the 1929 recording of Blind Lemon Jefferson playing “Eagle Eyed Mama”

.

.

Click here for details on how to enter your story in the Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

.

Click here to read “Constant at the 3 Deuces” by Jon Zelazny, the winner of the 57th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

.

.

.