.

.

.

Jazz in Available Light, Illuminating the Jazz Greats from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s is one of the most impressive jazz photo books to be published in a long time. Featuring the brilliant photography of Veryl Oakland — much of which has never been published — it is also loaded with his often remarkable and always entertaining stories of his experience with his subjects.

With the gracious consent of Mr. Oakland — an active photojournalist who devoted nearly thirty years in search of the great jazz musicians — Jerry Jazz Musician regularly publishes a series of posts featuring excerpts of the photography and stories/captions found in this important book.

In this edition, Mr. Oakland’s photographs and stories feature Art Pepper, Pat Martino and Joe Williams.

.

.

All photographs copyright Veryl Oakland. All text excerpted from Jazz in Available Light, Illuminating the Jazz Greats from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s

.

You can read Mr. Oakland’s introduction to this series by clicking here

.

.

_____

.

.

© Veryl Oakland

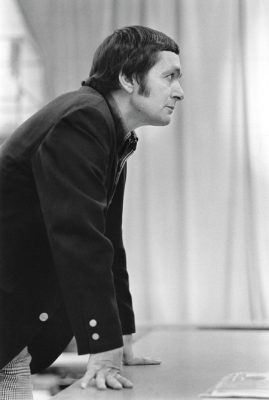

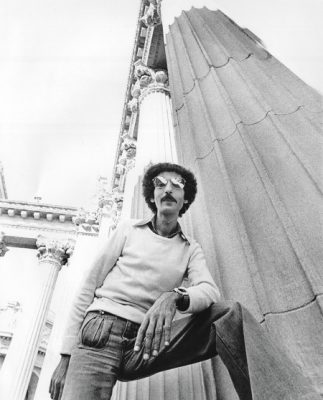

Careers Saved by Significant Partners (Take 1)

Art Pepper

San Francisco, California

‘

For the longest time, Art Pepper’s career had been going nowhere – throughout much of the 1950s and ‘60s, he had been imprisoned because of heroin addiction.

My introduction to Pepper’s raw talent came with the release of his 1957 Contemporary Records album, Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section. From the time I acquired that disc, I too, became hooked, marveling at how the hard-edged alto saxophonist was able to mesh so passionately with Miles Davis’s impeccable timekeepers from that period – pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Philly Joe Jones.

I longed to see and hear the man in person, yet never thought I would get the opportunity. But then in 1974, after he married his third wife, Laurie, I began seeing the reports that Art Pepper’s life was beginning to change…that he was about to make a genuine resurgence on the scene.

It was March of 1975 when I learned he would be serving as clinician and guest artist at the University of Nevada’s annual jazz festival in Reno hosted by the school’s jazz studies department.

Art Pepper had begun a revival. Not only was he now a popular and in-demand clinician for universities across the country, but within a few months Contemporary would release his “comeback” recording, Living Legend, featuring pianist Hampton Hawes, bassist Charlie Haden, and drummer Shelly Manne.

The morning of the event, I headed east over The Sierras. There, I spent most of the day in his midst at the soundcheck, and later, while he conducted classes for the enthralled students. That evening, in a solo performance with the University jazz band, Art Pepper brought the house down. Watching the man at work, I would never have guessed that he had been in such torment early in his career.

From that time forward, with Laurie’s nurturing and constant attention, Art simply bloomed. For the next six years, Pepper fronted or co-led several dozen acclaimed recordings, as well as proved to be a solid draw on the international festival circuit. For a time, he was the hottest property in Japan, literally revered by his many jazz fans.

In October of 1981, I caught him one final time as featured soloist with the Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra at the San Francisco International Jazz Festival. Backstage in his dressing room with his wife Laurie, Art was in good spirits. Outwardly, he didn’t appear to be placing much importance on his apparent “rebirth” as a musician. The fact that he was back performing at such a high level was simply as it should be. In my eyes, he was living completely in the moment, content knowing he was right alongside the person he considered his savior.

At one point before the show, he found himself without a neck strap for his alto, and the backstage hands ran around trying to find something that would work as a substitute. Eventually, someone produced a handful of twisted plastic wire, and Laurie fashioned some sort of hook to it so Art would be able to keep his horn in place.

While he was waiting to be called onstage, I took several candids of Pepper as he was warming up. Then, after placing his horn back in the case, Art leaned over and said to me, “Hey, you’ve gotta catch this. I’m going to pretend to be giving my last concert while having a heart attack.”

]

.

© Veryl Oakland

Dutifully, I snapped away.

After getting back up from the floor, Art and Laurie shared a big laugh over his joke. Ever in the moment, Art Pepper could make light of where he was and who he’d become.

Sadly, in June the following year, Art passed away at age 56 from complications following a stroke.

Critic Larry Kart, who witnessed the alto saxophonist in performance just days before his passing, wrote this of Art Pepper in his book, Jazz In Search of Itself: “On any given night until the very end – his last Chicago performance, which took place only two weeks before his stroke was typical – Pepper challenged himself to the utmost. In his life, Art Pepper seemed to be skating at the edge of an abyss. And yet his music managed to encompass that sense of danger, seeking and finding a wholeness that was, so it seems, denied to its maker.”

.

.

© Veryl Oakland

Arthur Edward (Art) Pepper, Jr.

alto saxophone; also tenor and soprano saxes, clarinet, flute

Born: September 1, 1925

Died: June 15, 1982

.

.

Click to listen to Art Pepper play the 1980 recording, “Blues in the Night”

.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

© Veryl Oakland

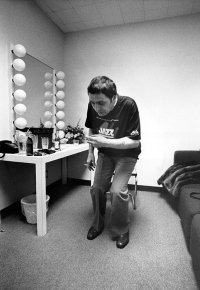

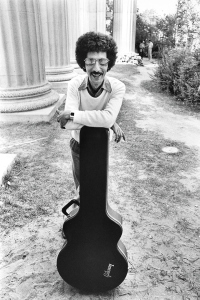

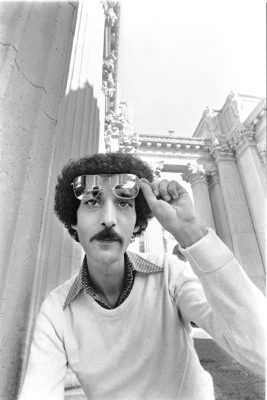

Calm Before the Storm

Pat Martino

San Francisco, California

.

Every once in awhile, I wonder what it might be like to reach out to the man again…to reconnect, and possibly even relive those enjoyable moments we had together that late 1976 weekend in San Francisco. After all, I was sharing the afternoon with one of a handful of my all-time favorite jazz guitarists, Pat Martino.

But, of course, that could never have happened. Even if it had been one of his greatest experiences ever, Pat wouldn’t remember me or our afternoon together. That’s because just a few years after our visit – in 1980 – Martino’s lifelong, but misdiagnosed, struggle with AVM (arteriovenous malformation) would culminate in a brain aneurysm and near death.

.

© Veryl Oakland

Life for Pat Martino would have to start all over again.

The guitarist was four years younger than me, just a skinny kid in his early twenties, when I first saw him perform with alto saxophonist John Handy and vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson at the inaugural University of California, Berkeley Jazz Festival in 1967. Despite clearly being the youngest, smallest person onstage, he caught the audience by surprise when he took one solo, weaving together a meticulous flow of blistering eighth note phrases. It was amazing.

Handy recalled those times, saying, “He was a tiny guy, but he played big music. He could play his little ass off, man.”

Every time I witnessed Martino’s future performances, he did things that were totally surprising, even revelatory. He never disappointed.

When we met for our photo session that afternoon at the Palace of Fine Arts, Pat was joined by his newest pianist, Berklee College of Music alum Delmar Brown. The two were in the midst of an international tour promoting their Warner Brothers release, Joyous Lake, which would become one of the finer jazz-fusion recordings from that period. The guitarist was jovial and upbeat our whole time together. It was obvious that Pat Martino was enjoying the fruits of his ever-expanding career.

It was only many years later, following his miraculous surgery, that I learned the details of Martino’s life-altering course through his revealing autobiography, Here and Now! In it, Pat chronicled how he overcame the devastating effects of memory loss, depression, anxiety, and overwhelming negativity throughout an arduous recovery period. I discovered how it took years for him to re-learn his art and re-emerge as one of today’s most vibrant and inspiring performers.

It occurs to me that all of us in the jazz community have been truly blessed, given a second chance to see and hear two highly-productive – and beyond talented – walking miracles: Pat Martino and Quincy Jones, who also survived a brain aneurysm and surgery in 1974. Both escaped near death and just kept on contributing, kept on creating some of the greatest music for us all to enjoy.

.

.

© Veryl Oakland

Pat Martino (Pat Azzara)

guitar, composer

Born: August 25, 1944

.

.

Click to listen to Pat Martino play the 1976 recording “You Don’t Know What Love Is”

.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

© Veryl Oakland

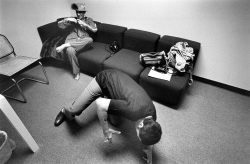

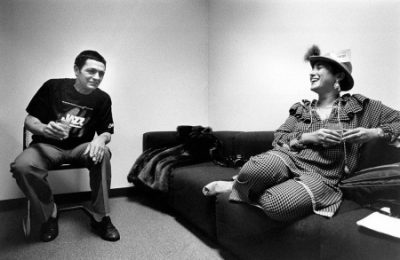

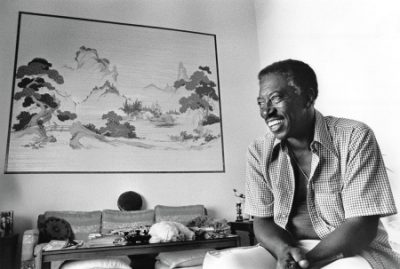

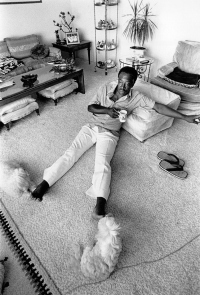

Some Rare “Down Time”

Joe Williams

Las Vegas, Nevada

.

.

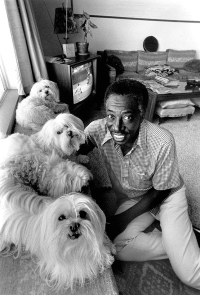

It was a late morning in August, 1977, when I finally caught up with the popular, globetrotting jazz and blues singer at his home in Las Vegas. Joe Williams had just returned the day before from his most recent junket, a multi-city tour of Japan where he had been sharing the stage with the popular vocalist Nancy Wilson.

When I arrived at his door, I was greeted by both Joe and his British-born wife, Jillean. After we introduced ourselves, Joe was quick to say, “I hope you don’t mind, but this is going to be a relaxed session.”

Joe poured coffee and we talked about his ever-busy, but always enjoyable, life on the road. He reminisced about some of his most memorable engagements over the years, particular those involving the high-profile big bands.

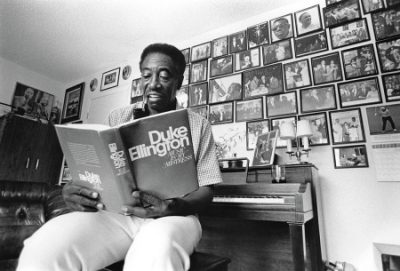

Having broken in during his early days with the likes of Coleman Hawkins’s and Lionel Hampton’s Bands, he lit up when he shared what it was like to perform with such giants of the day as Duke Ellington, Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson, the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Band, and especially, Count Basie, with whom he worked for seven years.

Joe Williams, with Duke Ellington at the 1970 Monterey Jazz Festival

.

© Veryl Oakland

It was always a most reciprocal arrangement. While he was quick to praise the great bandleaders who hired him, they too basked equally from the adoration of the crowds. The leaders understood perfectly that Joe Williams’s resonant baritone and engaging stage demeanor would always be a big hit, adding much to the ensemble’s overall presentation, as well as the box office receipts.

Joe explained that Las Vegas was a good place to call home. It allowed him the opportunity to get in some rounds of golf “…so I can maintain my respectable eight handicap.” On this trip, he would also get the latest news from bassist Monk Montgomery and the Las Vegas Jazz Society, as well as sit in with singer-songwriter Jon Hendricks, who was performing at the area’s only jazz club, The Tender Trap.

At one point, while alternately sipping coffee and watching a baseball game on TV, Joe got up from the sofa and stretched out on the carpet. It was like a signal. His and Jillean’s Pekingese/poodle-mix dogs Tosh, Pookie, and Roo immediately jumped down from a ledge and took turns licking his feet.

.

© Veryl Oakland

Because I knew the strong bond that existed between Joe Williams and Count Basie, near the end of our visit I brought up the bandleader’s name, noting that he would be returning to the Monterey Jazz Festival stage in just a few weeks (Basie was a no-show the previous year because of a heart attack).

“My bags are already packed,” Joe exclaimed. “Base is in great shape and I can’t wait to see him.”

As I was about to head out the door, I noticed an opened, hard-bound book lying on the piano bench. It was Duke Ellington’s Music Is My Mistress. I asked Joe for a final candid of him with the book. Some time later, I read the Maestro’s glowing review of the great jazz and blues artist: “…(Joe Williams) sang real soul blues on which his perfect enunciation of the words gave the blues a new dimension. All the accents were in the right places and on the right words.”

Joe Williams truly enjoyed the best of both worlds. Even when the popularity of the big bands diminished, he stayed very much in demand, often working with his own groups or alongside such diverse headliners as Clark Terry, Cannonball Adderley, Dave Pell, and George Shearing. Steady bookings brought him to major jazz festivals, plus the name clubs and hotels across Europe, Japan, and the US. He kept busy an average of 40 weeks a year.

.

.

© Veryl Oakland

Joe Williams (Joseph Goreed)

singer

Born: December 12, 1918

Died: March 29, 1999

.

.

Click here to listen to the 1979 recording of Joe Williams singing “If Dreams Come True”

.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

Click here to read the edition featuring Stan Getz, Sun Ra and Carla Bley

Click here to read the edition featuring Art Pepper, Pat Martino and Joe Williams

Click here to read the edition featuring Yusef Lateef and Chet Baker

Click here to read the edition featuring Mal Waldron, Jackie McLean and Joe Henderson

Click here to read the edition featuring Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer and Johnny Griffin

Click here to read the edition featuring Thelonious Monk, Paul Bley and Cecil Taylor

Click here to read the edition featuring drummers Jo Jones, Art Blakey and Elvin Jones

Click here to read the edition featuring Monk Montgomery and the jazz musicians of Las Vegas

Click here to read the edition featuring Sarah Vaughan and Better Carter

.

.

.

.

.

All photographs copyright Veryl Oakland. All text and photographs excerpted with author’s permission from Jazz in Available Light, Illuminating the Jazz Greats from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s

.

You can read Mr. Oakland’s introduction to this series by clicking here

Visit his web page and Instagram

.

.

.