.

.

.

…..Jazz in Available Light, Illuminating the Jazz Greats from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s is one of the most impressive jazz photo books to be published in a long time. Featuring the brilliant photography of Veryl Oakland — much of which has never been published — it is also loaded with his often remarkable and always entertaining stories of his experience with his subjects.

…..With the gracious consent of Mr. Oakland — an active photojournalist who devoted nearly thirty years in search of the great jazz musicians — Jerry Jazz Musician regularly publishes a series of posts featuring excerpts of the photography and stories/captions found in this important book.

In this edition, “Keeping Jazz Alive in the Desert,” Mr. Oakland’s photographs and stories focus on bassist Monk Montgomery’s efforts to bring jazz to Las Vegas, and the notable jazz musicians who played in that city

.

.

.

All photographs copyright Veryl Oakland. All text excerpted from Jazz in Available Light, Illuminating the Jazz Greats from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s

.

You can read Mr. Oakland’s introduction to this series by clicking here

.

.

_____

.

.

Keeping Jazz Alive in the Desert

.

© Veryl Oakland

.

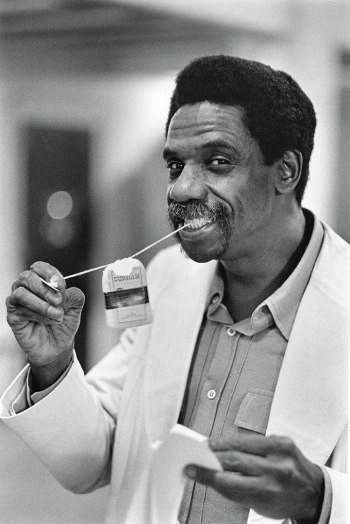

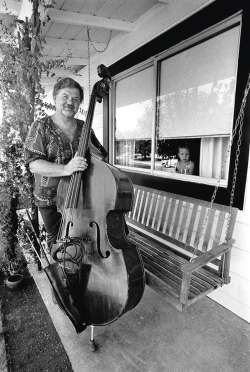

Monk Montgomery

Las Vegas, Nevada

.

…..Among the many blessings that jazz offers is the vast number of incredibly talented musicians who have come from the same families. For starters, there are the Jones brothers – pianist Hank, trumpeter Thad, and drummer Elvin; the Heath brothers – saxophonist Jimmy, bassist Percy, and drummer “Tootie”; the Marsalis family – father and pianist Ellis Jr., trumpeter Wynton, saxophonist Branford, trombonist Delfeayo, and drummer Jason; and the Montgomery brothers – guitarist Wes, vibraphonist-pianist Buddy, and electric bassist Monk.

…..Of the Montgomery brothers, it was Wes who, deservedly, commanded most of the jazz world’s attention. Using his thumb instead of a plectrum, the guitarist enhanced his already identifiable warm sound by implementing an impeccable octave technique (simultaneously voicing the melody line in two registers), even on the most difficult, extended solos. No one since Charlie Christian has been more imitated, or has had a greater impact on guitarists, than Wes Montgomery.

…..But it was Monk, the eldest of the Montgomery brothers, who I consider to be one of modern music’s most underappreciated and unheralded champions: in fact, I’d say that a more passionate, tireless, behind-the-scenes promoter of jazz and its outstanding artists would be hard to find.

…..Monk Montgomery could well be the most unlikely figure in jazz to have had a major impact on this music’s rich history. He didn’t even begin playing bass until age 30, yet within a few months had honed sufficient chops to make it in Lionel Hampton’s Orchestra, with whom he toured from 1951-’53. While with Hampton, Monk introduced to the public his pioneering skills by becoming the first to play an electric bass guitar, the Fender Precision.

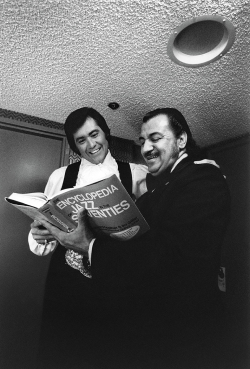

…..Writing in The Encyclopedia of Jazz in the Seventies, producer-arranger Quincy Jones, who played trumpet in the Hampton band at the same time, said, “…1953 locked up the incubation period for the granddaddies of electronics. Specifically, there was Charlie Christian, who established the electric guitar in 1939; and in 1953…Monk Montgomery was playing fender bass – the first musician ever to use one. Those two instruments turned the whole thing around…. Basically, the thrust of evolution was motivated by the electric guitar and fender bass.”

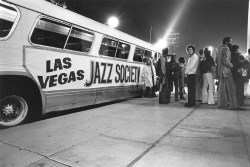

…..I got an up-close glimpse of Monk Montgomery’s passion for jazz promotion when I met with him for the first time in November of 1975 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. As founder of the Las Vegas Jazz Society (LVJS), he had booked a tour bus, filled it with his fellow jazz fans from the desert, and made the long haul to catch the “1st Annual World Jazz Association Concert” featuring the Quincy Jones Orchestra, plus an all-star lineup of jazz giants.

…..Following the afternoon soundcheck, I sat down with Monk and listened as he raved about all the things the LVJS was doing to promote jazz in the nation’s entertainment capital. The more he shared, the more animated he became. By the time we finished talking, I was convinced that his personal story needed to be covered.

…..Over the next several months, I reached out to various editors who I thought might be interested in publishing a photo report about Monk Montgomery and his devotion to making jazz music commercially compatible with Las Vegas. Finally, I got a note from the editors at Swing Journal magazine in Japan. They agreed that their readers would be interested in knowing the story about the Montgomery brother who was making jazz a significant part of the Las Vegas musical landscape. I was asked to photograph as many of the legitimate jazz artists who were still active and calling this city their home.

…..After sharing all this information, Monk told me he would find out when the majority of the Las Vegas jazz musicians would all be in town at the same time so as to maximize my coverage. A few weeks later, he called back and we agreed on a weekend in August of 1977.

…..When I reconnected with Monk, this time at his home, he had already put together a list of all the musicians who would be awaiting my call. Before leaving, we did a brief photo session, and because I was curious, I asked him to share how his hard-earned quest to put jazz on the Las Vegas map all came to pass.

…..Monk told me that after several years of touring and recording with brothers Wes and Buddy as the “Mastersounds,” he moved here in 1970 to take a job with vibraphonist Red Norvo and his trio. For the next year-and-a-half, he played steadily at the Tropicana Hotel on the Strip. Monk was happy to be in Las Vegas, believing his jazz future in this desert resort would be good.

…..But then the job abruptly ended. The cold reality came when Monk started looking for other jazz gigs. He went around to the clubs and lounges, talking with entertainment directors – yet there was nothing in the way of regular work to be found. For the next two years, he single-handedly met with the Las Vegas entertainment hierarchy to pitch the need for quality jazz. Without any compensation, he offered to book compatible players, arrange available dates, and literally do all the legwork to bring in top jazz talent. Still there were no takers.

…..It made no sense to Montgomery. As he questioned, “You can see top name jazz artists in Japan, throughout Europe, across the United States – many of whom live in LA, just 280 miles away – but they don’t appear here? What’s with that?”

…..Unwilling to accept defeat, Montgomery decided that some kind of non-profit jazz organization had to be formed. He invited two close friends representing the business and education communities who were well-connected with the local political scene in for a serious meeting. A week later, 35 other business professionals who had an appreciation for jazz came on board.

…..In April of 1975, Monk Montgomery founded the Las Vegas Jazz Society, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to bringing jazz to the attention of the Strip hotels, club owners, the education establishment, and music fans throughout the region. They started a membership drive, began printing stationery, made posters, and did all the other jobs necessary to get the society off the ground.

…..Right away they began booking concerts. Working with the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), Montgomery brought his first jazz act to town – trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and his quintet featuring tenor saxophonist Junior Cook, pianist George Cables, bassist Henry Franklin, and drummer Carl Burnett. Vocalist Joe Williams opened the show. The student union ballroom sold out.

…..Later that year, he brought the Dizzy Gillespie Quartet, then Milt Jackson, and the LA Four. Before long, such acts as the Louie Bellson Big Band, the Ron Carter Trio with Sarah Vaughan, Count Basie’s Orchestra, Max Roach, Phineas Newborn, Jr., and Herbie Hancock’s Quintet all came through on tour. Monk was also instrumental in bringing many jazz bookings to the Strip hotels: Maynard Ferguson and his band headlined at the Stardust; Stan Getz and Bob Brookmeyer performed at the Sahara; even such diverse acts as Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chick Corea, Herbie Mann, Jean-Luc Ponty, and the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra all made it to the big stages.

…..Always in search of new promotional opportunities, Montgomery took over as host of a Sunday evening jazz show on KLAV Radio called the “Reality of Jazz” to plug the many worthwhile activities of the Las Vegas Jazz Society. Presenting the best in jazz music, Monk also featured live, in-studio interviews with visiting jazz musicians, as well as open mic discussions with top artists to share what was happening with them while they were on tour. The ultimate compliment was paid one evening when – unannounced – Count Basie, Oscar Peterson, Tommy Flanagan, Joe Pass, and Louie Bellson all crammed into the studio with Monk for an animated discussion.

…..After our weekend together, we continued to stay in touch. The indefatigable promoter always had important jazz projects on the front burner, even helping to head up major events as far away as Lesotho, South Africa. Another person in his shoes taking on such a noble cause would likely have focused more on his own self-aggrandizement. Not Monk Montgomery. Putting jazz front and center was always the goal, the greater good. To me, he will always be remembered as one of the jazz world’s great ambassadors.

.

© Veryl Oakland

William Howard (Monk) Montgomery – bass, composer

Born: October 10, 1921

Died: May 20, 1982

.

.

Listen to the 1961 recording of the Montgomery Brothers (Wes on guitar, Buddy on piano, Monk on bass) play “Groove Yard”

.

.

_____

.

.

The Other Las Vegas Notables

…..During the remainder of my stay, I tracked down and photographed all nine of the working musicians on the list Monk had provided. Every one of them praised Monk Montgomery for his passion and perseverance in making “Jazz” and “Vegas” compatible.

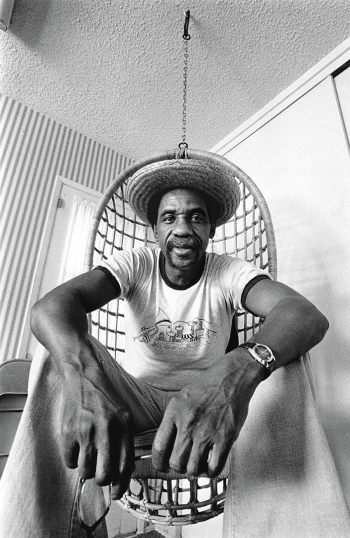

…..My first contact was with elder jazz statesman Garvin Bushell, perhaps the most musically-diverse of all the artists I met that entire weekend.

…..The multi-reeds specialist who was then just a few weeks shy of his 75th birthday, had first broken in with Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds in the 1920s. From there, he joined Fats Waller, followed by performances in the orchestras of Fletcher Henderson and Cab Calloway. Clearly proficient in any setting and a master of virtually all the woodwind instruments, he later went on to record with such contrasting stylists as John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, and the Gil Evans Orchestra.

…..Bushell told me that he had settled in Las Vegas about the same time as Monk Montgomery, and reiterated just how smart the man was as a businessman. Among the many gigs he enjoyed with Monk’s support included playing in the orchestra with Sammy Davis, Jr. at Caesar’s Palace, backing a variety of stars such as vocalist Carmen McRae at locally-produced jazz concerts, and subbing for other musicians in the big hotels whenever needed.

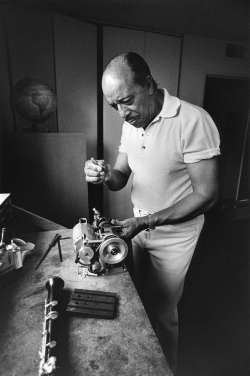

…..When he wasn’t performing, Garvin maintained the same kind of success he enjoyed when he worked as a woodwinds teacher in New York. Here, he was giving lessons to 50 students a week. In what little spare time remained, Bushell kept busy making repairs on his many reed instruments in the home workshop.

…..Joking about one of his earlier involvements here in the desert, Garvin shared with me what happened when Monk tried to land him a job in the relief band at the Dunes Hotel. “A friend of mine told me, ‘Garvin, they’re not going to hire you. First place, you’re black. Second, you’re old. Third, you don’t have hair.’”

…..Note: The ever-involved Bushell would go on to write a most highly-acclaimed autobiography, Jazz from the Beginning, that included his rich experiences performing with many of the world’s greatest musicians.

…..I connected with the remaining musicians in the comfort of their homes, or backstage at various Strip hotels while their respective orchestras were on break. Because of their special talents, each of the artists had successfully carved out particular niches and was enjoying steady work in the desert entertainment capital. They included:

.

© Veryl Oakland

Si Zentner

…..The bandleader-trombonist, who won an amazing 13 consecutive Down Beat “Best Big Band” polls in the 1950s and ‘60s, pretty much defied all odds by continuing to head up quality orchestras long after the big band era had faded. He held the distinction of being named musical director for the Tropicana Hotel’s Les Folies Bergere, which would become one of the longest-running floor shows in Las Vegas.

.

___

.

© Veryl Oakland

Tommy Turk

…..Trombonist Tommy Turk is remembered for his performances and recordings with bebop pioneer Charlie Parker, and his nearly two years with Norman Granz’s popular Jazz At The Philharmonic tours, playing with such greats as Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young.

.

___

.

© Veryl Oakland

Billy Root

…..Multi-reeds player Billy Root, relaxing backstage at The Frontier Hotel between shows, early on recorded with the Stan Kenton Orchestra, and later with trumpeters Roy Eldridge and Lee Morgan. In one of his early claims to fame – as the house tenor saxophonist at Philadelphia’s Blue Note club in the 1950s – Root played with the top soloists of every major act that passed through.

.

___

.

© Veryl Oakland

Carl Fontana

…..A mainstay in Woody Herman’s many Herds during the 1950s and ‘60s, trombonist Fontana – shown during a morning rehearsal – was serving as lead trombonist for the Paul Anka show at Caesar’s Palace. With his technically-brilliant mastery and ability to execute smooth, rapid-fire passages, the trombonist made any bandleader feel blessed to have such an anchor in the brass section.

.

___

.

© Veryl Oakland

Carson Smith

…..Among jazz followers, bassist Carson Smith was best known for his work with Gerry Mulligan, the baritone saxophonist who introduced the jazz world to his influential pianoless quartets. When I told Carson where my Las Vegas photo report would be published, he lit up, sharing the story of his 1964 tour of Japan with saxophonist Georgie Auld. “The Japanese are true jazz fanatics,” he said. “They know everybody. When I got off the plane, there were dozens of people all waiting in line to see us at the airport. As I walked by, they bowed and said, ‘Carson Smith, the bassist.’ It was an incredible experience.”

.

___

.

© Veryl Oakland

Elek Bacsik

…..Early in his career as both a violinist and guitarist, the Hungarian-born gypsy and cousin of Django Reinhardt worked throughout Europe with pianist Bud Powell and drummer Kenny Clarke.

.

© Veryl Oakland

…..My introduction to Bacsik came when I heard his distinctive guitar sounds on the 1962 Dizzy Gillespie album, Dizzy on the French Riviera. Soon after arriving in Las Vegas, Bacsik made such a strong impression on the popular headliner, Wayne Newton, that the singer chose Elek as his full-time concertmaster and leader of the string section.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

Click here to read the edition featuring Stan Getz, Sun Ra and Carla Bley

Click here to read the edition featuring Art Pepper, Pat Martino and Joe Williams

Click here to read the edition featuring Yusef Lateef and Chet Baker

Click here to read the edition featuring Mal Waldron, Jackie McLean and Joe Henderson

Click here to read the edition featuring Dexter Gordon, Art Farmer and Johnny Griffin

Click here to read the edition featuring Thelonious Monk, Paul Bley and Cecil Taylor

Click here to read the edition featuring drummers Jo Jones, Art Blakey and Elvin Jones

Click here to read the edition featuring Monk Montgomery and the jazz musicians of Las Vegas

Click here to read the edition featuring Sarah Vaughan and Better Carter

.

.

.

All photographs copyright Veryl Oakland. All text and photographs excerpted with author’s permission from Jazz in Available Light, Illuminating the Jazz Greats from the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s

.

You can read Mr. Oakland’s introduction to this series by clicking here

Visit his web page and Instagram

.

.

.