December 5th marks the 41st anniversary of the bebop trumpeter Kenny Dorham’s death. Only 48 years old at the time of his passing from kidney disease, Dorham’s professional life enjoyed a great measure of respect from his fellow musicians, but, as Nat Hentoff pointed out in the liner notes to Dorham’s 1963 Blue Note recording Una Mas, “he has yet to break through to the kind of wide public acceptance which has occasionally seemed imminent.” His recordings are timeless – each and every one packed with delicious passion and brilliant playing that still sounds fresh — but Dorham never did “break through” in his lifetime, and continues to be classified by important jazz historians as “underrated.” In a Jerry Jazz Musician-hosted conversation on underrated jazz musicians, the most eminent jazz writer Gary Giddins said “when anybody wrote about [Dorham] it was de rigeur to preface his name with that word.” While the “break through” to a wider audience Hentoff wrote about was important to Dorham, to him, “if it’s going to happen, it’ll happen…However it goes, I’ll just keep playing. That’s where the basic satisfaction is at.”

His music remains more than basically satisfying to his listeners. It smokes! Check out Whistle Stop, a recording Giddins calls “one of the great jazz albums,” as well as Una Mas, on which tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson made his debut. Dorham is also found on many other records as leader, and in the bands of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Lionel Hampton, Thelonious Monk, Art Blakey, Sonny Rollins and Max Roach.

_____

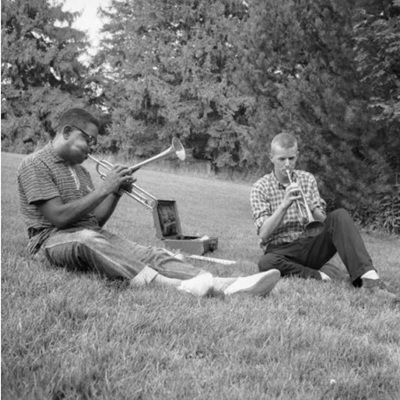

Kenny Dorham Quartet in Stockholm, 1963

“Whistle Stop”

_____

The following “Conversation with Gary Giddins” is from a January 5, 2004 interview, where the topic was underrated musicians. This excerpt focuses on underrated trumpeters, which Dorham was characterized as throughout his career

*

JJM In your final Village Voice column of December 15, 2003, you lamented about not having written columns on the likes of Booker Ervin, Charlie Rouse, Wardell Gray and others.

GG When I mentioned musicians like Wardell and Rouse in that column, I was very consciously limiting myself to dead musicians, because once we expand the dialogue and include living musicians, it can be an endless thing. Dave Liebman, for example, is somebody I never wrote a column about, though I’ve often thought about it. I wrote quite a bit about Anthony Braxton in the early years, but insufficiently about his later work. There are many others.

JJM Perhaps this is a good time, then, to discuss neglected and underrated jazz musicians in general. I thought we could go instrument by instrument, starting with the trumpet.

GG One musician I wanted to write about is Malachi Thompson — I must have started a column on him four or five times, but something always intervened. He’s a trumpet player from Chicago, not a great virtuoso, but a solid player who works within the bebop idiom but does so using a variety of avant-garde bells and whistles. He allows himself and those who work with him lots of freedom, yet it is disciplined. There’s usually some sort of harmonic predisposition in the way he plays. I would call him an inventive recording artist, because his albums are often thought through conceptually, and, of course, he’s an engaging soloist. I don’t always like when he gets into vocals and poetry and that kind of thing, but he’s been out there a long time, making a commanding series of records — mostly for Delmark — that haven’t gotten much attention. There are many musicians like that; you feel your way into their work and try to get a grip on it, and sometimes it takes longer than you would like.

Another trumpet player that I never actually did a whole column on — and it sort of spooks me that I didn’t because he’s one of my favorites — is Fats Navarro, one of the very pivotal players of the late forties. I wrote a number of times about Clifford Brown, who in some ways arrived as Navarro’s heir apparent, but he’s another musician I feel I never did justice to because he takes my breath away. I can’t imagine life without Clifford Brown. I rate him pretty close to the top. But I think I need to say here that the decision about what I wrote about was partly affected by circumstances and partly by my own craziness. For example, when the complete Navarro Blue Notes were collected, that would have been a good opportunity, but more pressing stories may have intervened, or maybe I had just done a couple of historical pieces and was focusing on newcomers — I always attempted to balance old and new. The craziness is more emotional — I have to get myself worked up by someone’s music to write at length about it.

JJM I think Brown is underexposed, at least to the present day audience.

GG At this point he may be, but certainly anyone who grew up with jazz knows that Clifford is practically a holy figure. I don’t think it’s unfair to say that his passing, some forty-eight years ago, is still mourned. When I listen to the tracks he recorded in a club in Philadelphia on the night of his death, “A Night in Tunisia” and “Donna Lee,” I am torn between utter exhilaration and tremendous sorrow for what he did not have the chance to become. Do you know his solo on “Delilah”? — the perfect trumpet solo. “I Can Dream, Can’t I” is another. And that opening solo on “Tunisia” is pure genius.

JJM Did you see Warren Leight’s play Sideman?

GG Absolutely. The scene I am sure you are reminded of is the one in which they play a tape of the “Night in Tunisia” solo. During the performance I attended, when that scene was over, the audience cheered and applauded. I was astounded by that. Here we were, watching a dramatic play, which basically comes to a stop while two guys sit at a bar and listen to a record for five minutes. That is unheard of in theatre. Yet the audience was enthralled, and when that solo was over, there was the kind of response you’d hear at a musical. That is so rare. Now, how many people in the theatre went out and bought a Clifford Brown album? That would be interesting to know, but I think the reaction indicates how powerful his music is.

JJM You were talking about Navarro before I got you sidetracked on Brown…

GG Yes. Navarro was one of the musicians whose influence you hear most predominantly in Clifford. He had an absolutely spotless sound and was a brilliantly inventive player. He was very different from Dizzy in that his phrases had a more cautious architectural structure that allowed him to sustain a luscious tone, and very different from Miles in that he was a solidly extroverted player. He was one of those musicians who, no matter what the moment called for, could come up with something creative, imaginative and exciting. Like Brown, he died terribly young — twenty-six — part of tragic cadre of trumpet players who died ridiculously early, including Sonny Berman, Clifford Brown, Booker Little, and Lee Morgan, who at least made it out of his twenties and died at thirty-three. Little was another unique trumpet player, who came along right after Brownie. The two trumpet players we usually think of from the early sixties are Freddie Hubbard, the great virtuoso, and Don Cherry, the great “free” player. Little walks between them. He is probably best known for his work with Eric Dolphy, but he was also an interesting composer. He never completely got his approach on track to the degree that Brownie and Fats did. But he was so imaginative, and when you listen to him now he still sounds modern in a suggestive way. He had a gorgeous sound, personal and supple.

JJM Nat Hentoff’s record company recorded Little if I recall

GG Yes, that’s right. Little wrote and recorded a suite for Candid, where Nat produced albums. Nat made a lot of good albums by Mingus, Phil Woods, a reunion of Hawkins and Pee Wee Russell, Otis Spann.

JJM What about Kenny Dorham?

GG Will Friedwald once wrote a piece for me in the Voice in which he said something like, if you look up “underrated” in the dictionary, it says, “See Dorham, Kenny,” because when anybody wrote about him it was de rigeur to preface his name with that word. Dorham was the other guy who came up during the late forties bop period who never quite achieved stardom. Yet, his Blue Note records — especially Whistle Stop, one of the great jazz albums — show that he had his own very sleek, very beautiful, and emotional sound. He loved long phrases that would kind of wind in and out of the changes, and he had a tremendous sense of time. He was a marvelous player. I’ll tell you a funny story about KD that involves another gifted and neglected trumpet player from the period of the late fifties and sixties, Ted Curson. Ted worked with Cecil Taylor and played beautifully on those Mingus Candid albums with Dolphy, and made a couple of very attractive albums on his own for Prestige and other small labels. In the sixties, he got a shot with Atlantic when his band had the equally underrated tenor saxophonist Bill Barron, Kenny’s big brother. So he made a really fine album called The New Thing and the Blue Thing, which shows off what an inventive tunesmith Ted was in that period, and KD was reviewing records for Down Beat. He reviewed Ted’s album and went on and on about how great it is, and gave it three and a half stars. Ted asked him, “Kenny, if you love the record so much, how come you gave it only three and a half stars.” And Kenny told him, “That’s what they gave [Dorham’s] Trumpeta Toccata, and that record’s just as good as yours.”

JJM Any other trumpet players come to mind that you feel were neglected or underrated?

GG There are so many players who are not written about anymore, especially from the swing period. When was the last time you read about Roy Eldridge or heard a representative reissue of his work in any period of his amazing career? Most of his recordings aren’t even available on American labels at the moment. He is someone I wrote a lot about at the Voice, so I don’t feel I overlooked him, but I can’t help but wonder what his name and music mean to a younger generation that is pretty much dependent on what is available on CDs.

There are many players from the thirties I enjoy. I was always fond of Bobby Stark, a big band player best known for his work with Fletcher Henderson. While I enjoy his work, he is somebody I wrote about only in passing. A lot of players like Stark get left by the wayside, and as time goes on, people forget about them. Bill Coleman, Benny Carter as a trumpet player (“More Than You Know” is a classic), Jabbo Smith, the great bluesman “Hot Lips” Page, even someone like Rex Stewart, who is remembered for his work with Ellington, but was such a striking, original, satisfying player on so many levels. Koch reissued the 1941 sides he and Johnny Hodges made leading Ellington small groups, and it created very little stir. When RCA-Vintage originally put that collection out in the 1960s, everyone was talking about it. In some ways, it’s even more powerful now. I wrote a long piece about it that will be in my next book, but I was surprised and disappointed that the reissue caused no stir at all. But in jazz, everyone is underrated. The majority of the people in this country don’t really know who Louis Armstrong was, so begin there

JJM Well, from a fan’s perspective, it is interesting to see who gets marketed most prominently. Among trumpet players, certainly Miles is up there, as is Dizzy. The person I keep running into in my studies of jazz is Red Nichols, so much so that I am left with the impression that the record companies have done an injustice to him in terms of marketing his music.

GG You’re going way back into jazz history now. It is hard to know what to do with Red Nichols. There are basically two groups of Nichols recordings, and those made in the twenties are the ones worth listening to — not so much for his playing but for the strange band he led, the “Five Pennies.” It had an unusual sound with Vic Berton playing tympani, and is still fun to listen to today. He used some great musicians, including Pee Wee Russell, who played a memorable solo on “Ida.” And I like Red’s solo on the Whiteman recording of “I’m Comin’ Virginia,” but he was not often an inspired player. Next to someone like Beiderbecke, he was decidedly second rate. Still, it would be nice if a label edited an anthology of the best of the early Five Pennies.

Then Nichols disappeared for a while and was rediscovered in the fifties as a consequence of The Five Pennies — a very silly biopic that starred Danny Kaye. Nichols became hugely popular because of it. At that time, he was recording for Warner Brothers, which had a jazz catalog in those years that consisted almost entirely of records by Nichols and other Dixieland musicians. The film and Nichols’s popularity spurred a revival of interest in that kind of music, but those records, despite featuring solid musicians, are pretty much by the numbers, second generation white Dixieland, and I don’t think they would find much of an audience today. But I do think there is enough material from his first group of records to justify a rediscovery of him.

*

I hope everybody eventually gets a chance to hear Kenny Dorham’s 1960 Quintet album called JAZZ CONTEMPORARY, Which featured Charles Davis and Steve Kuhn, unforgettable solos by all, great originals by Dorham, and arguably the definitive versions of “Monk’s Mood” and “In Your Own Sweet Way.” When I hear those, I feel like Monk and Brubeck are smiling in approval.

Thanks for the comment here, Terence. Not only is the music memorable but the cover art is terrific!

The truth is that Dorham is not a great soloist and has serious problems with his technique, his sound for instance is poor and very irregular.

I don’t know how you came to that conclusion bro!

Today is KD’s birthday, and that led me to this. What a pleasant surprise to see the two of you discussing the Night in Tunisia scene in Side Man.

I just listened to Jazz Contrasts and Quiet Kenny. For the commenter that thinks he is 2nd rate he just hasn’t a clue. Tone, phrasing, creativeness and eloquence permeates his trumpet playing. While he wasn’t a member of the near to 27 club, we still lost him too soon at 48 from Kidney failure.