.

.

.

“Jazz Duet II,” by Leo Meiersdorff

.

Two of a Mind

Conversations on Creative Collaboration

.

….. Introducing a new Jerry Jazz Musician series, showcasing interviews with musicians about the collaborative process. Periodically, contributing writer Bob Hecht will talk with the principals of a variety of jazz projects, exploring their interactions and the intimate nature of their collaborations.

…..To launch this series—and we happily acknowledge the classic Paul Desmond and Gerry Mulligan album of 1962 as the source for our title: Two of a Mind—we present interviews with pianist Bill Charlap and vocalist Sandy Stewart. Because Stewart and Charlap are not only outstanding artists but also mother and son, this is an especially intimate portrait, as Bob explores with them the art of accompanying singers.

.

.

_____

.

.

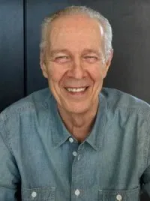

Sandy Stewart and son Bill Charlap

.

.

A Subtle Art

A Conversation On The Art of Accompanying Singers

with Pianist Bill Charlap and Vocalist Sandy Stewart

.

.

Introduction & Interviews by Bob Hecht

.

…..Accompanying a jazz-oriented vocalist is a subtle art, demanding a level of skill and sensitivity that can easily go under-appreciated. It can sometimes be a relatively thankless job—the spotlight is rarely on the person at the piano bench, nor do listeners typically buy a singer’s record because a particular accompanist is on the date. It has been said that as an accompanist you know you have done your job well if you have appeared to stay out of the way of the vocal, if all of the attention has been on the singer and the song.

…..Yet accompanying is a highly advanced, nuanced art. It is a process of musical and emotional attunement that has been likened to the intuitive interaction of two intimate dancing partners, able to anticipate one another’s every move. Some otherwise excellent pianists are good at it and others aren’t. As Carmen McRae told Art Taylor in his book, Notes & Tones, “An accompanist and a guy who can play the piano are two different things. Even if a guy can play his buns off, it does not necessarily mean he can accompany a singer. A guy must really love to do it.”

…..The pianists who are great at accompanying are able to merge with the vocalist, and to breathe as one at times. When one listens carefully to the best accompanists of the great jazz divas—Ellis Larkins with Ella Fitzgerald, for example; or Tommy Flanagan with Ella; Jimmy Rowles with Carmen McRae; Bill Charlap with Carol Sloane; Bobby Tucker with Billie Holiday; Ronnell Bright with Sarah Vaughan—you can hear the aural actions of subtle musical painters, offering the perfect, succinct introduction, remaining closely attentive to the singer’s breathing, inserting tasteful fills to augment the lines and the meaning of the musical story, adding bits of color here or a supportive foundation there—all in the service of creating the perfect setting for the vocal—so that the final result is a union, a true duet, a conversation between a singer and a pianist.

…..To begin to explore the dimensions of this special art, I talked with one of its most lauded contemporary practitioners, pianist Bill Charlap, and with a nonpareil vocalist with a deep appreciation for the art of accompanying, Sandy Stewart.

…..Charlap is a Grammy Award-winning jazz pianist and Director of Jazz Studies at William Paterson University. He has achieved widespread recognition as the leader of his own trio and has been an important sideman for the likes of Phil Woods and Gerry Mulligan. He also played as one-half of a remarkable piano duo on a critically-acclaimed recording (Double Portrait) with his wife, the highly regarded pianist Renee Rosnes. He has also accompanied such singers as the aforementioned Sloane, Tony Bennett, Barbra Streisand, Cecile McLorin Salvant, Ernie Andrews, Helen Merrill, Kurt Elling, Freddy Cole—and not least of all, Sandy Stewart.

…..Stewart has a special place in Charlap’s life, as she literally gave birth to him back in 1966. She was married at that time to Bill’s father, composer Morris “Moose” Charlap, best known for his work on the Broadway show Peter Pan, as well as for composing several enduring popular songs. Moose died when Bill was a young boy. Sandy had a notable career as a singer on many of the leading radio and TV shows of the fifties and sixties. During her long career she has been accompanied by many great pianists including Dick Hyman and Mike Renzi. She is admired for her spot-on intonation, her powerfully understated way of expressing the deep feeling of a lyric, and her sensitive phrasing and time.

…..Bill Charlap took to the piano at a young age and immersed himself in jazz and in the music of the Great American Songbook. It was perhaps inevitable that at some point he would accompany Sandy in performance and recordings. They have recorded several times together, with two duo recordings standing out: Love Is Here to Stay, and Something to Remember. It is not hyperbole to say that Sandy and Bill work together like hand-in-glove. Together, they embody a love and mastery of the Great American Songbook—their collaborations have been called a virtual master class in interpretation of the Songbook—and they perhaps best capture the intimacy of the art of accompanying, for this mother and son duo understand one another and respond to one another’s every nuance, with their unique DNA-based musical chemistry.

.

Bob spoke with Bill and Sandy in separate phone conversations in April, 2019.

.

.

Listen to “The Best Thing for You” by Sandy Stewart and Bill Charlap, from their 2013 album, Something to Remember

.

.

___

.

.

.

A Conversation With Bill Charlap

.

BH Today, Bill, we’re exploring the art of accompanying singers. It seems to me that while accompanying a horn player isn’t fundamentally different than accompanying a vocalist, at the same time it does seem that there is a very particular art to accompanying singers. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the process, on the interaction between vocalist and pianist. And to start I’d like to get your reaction to something the wonderful singer Carol Sloane—whom you have accompanied on several recordings—said once about accompanying. Referring to her accompanist at the time, Norman Simmons, she said, “Norman knows when not to play and that is perhaps the greatest attribute of an accompanist, in the exalted tradition of Jimmy Rowles and Bill Charlap.”

BC Well, that’s a very nice thing that she said, I’m glad to be included there. First of all, I affirm everything that you said, Bob, in your exposition, about there not being a big difference between playing with any other instrumentalist in any context, and accompanying, because you are always in conversation. But let’s get right to what you’re talking about, which is accompanying a vocalist.

“An accompanist needs to weave a carpet for the vocalist to get the story across.”

One of the things a vocalist has—the thing that a vocalist has that a horn player does not—are words. And words are the story, and words also have their own music. And an accompanist needs to weave a carpet for the vocalist to get the story across. The story of the words, the lyrics; and every harmony that an accompanist chooses is just like what a painter is doing when they’re choosing color for a painting. Every color has weight, and every color has value. And so, harmony has to do with the bass note and the melody note, and the quality of the harmony—whether it’s major, minor, diminished or augmented and any variant thereof of any of those type of chords. But it also has to do with the disposition of that chord. Is it a fire engine red? Or is it a maroon red? Or is it kind of a purple. They’re all reds. But first you need to choose your color and then you need to choose your shade. And all of this is extemporaneous and all of this should be in conversation with the vocalist. And all of these choices are made, of course, in a split second because we are jazz musicians, and so we create extemporaneously.

BH In an interview with Sandy Stewart, your mom, I heard her talk about your musical relationship, and she said that when you accompany her it’s like you know when she’s going to breathe.

BC Well I do. I mean, she’s my mom, so there’s something extra there and there’s some sort of DNA thing that happens. And that is true, I can sense how she’s moving. It’s a very natural thing. But really it’s just working with a really great musician whose phrasing of course I’ve grown up listening to—ever since I knew I was listening to it for any reason other than I’d just heard it. (Laughs)

But I think your intuition becomes very heightened as a jazz musician. [Drummer] Kenny Washington is one of the world’s greatest accompanists. We’re talking about pianists, and he’s a drummer. And he listens with the same type of attention to detail. I’ve heard him with singers, and within my trio and in many other contexts. So I’m just saying that any great jazz musician on any instrument uses all of those things, I think. It’s not just the pianist’s or the guitarist’s special relationship with the singer, although that’s a special relationship complete unto its own. But I believe that’s how we need to approach each other all the time. And I think the greatest players have a very wide-ranging scope that way.

.

A musical interlude: “Somebody Loves Me” Sandy Stewart with Bill Charlap from the 2013 album, Something to Remember

.

BH When you were growing up, and developing as a pianist, did you and your mom work on things at home, did she give you any specific kind of guidance, or was a lot of this by osmosis?

BC No guidance. And we didn’t play together at home at all. We worked when I was ready to work with her. I wasn’t really accomplished enough to play for her until I was about nineteen or so and then we started working together. And I learned by making mistakes! (Laughs) I learned by really listening…and I think it was very natural. I didn’t need anyone to tell me, ‘do this’ or ‘don’t do that.’ The following and the leading was very natural.

BH The pianist Mike Wofford, who has accompanied many of the great ladies of song, including Ella, Sarah and Carmen, told me he had learned so much about accompanying from playing for those great vocalists. So I wonder what certain singers have taught you about accompanying.

BC Each singer has their own way of approaching the drama of the story that they tell. So you learn all kinds of ways of approaching the drama of the song. Also, they have different ranges, so when you’re playing for Gerry Mulligan on the baritone saxophone it’s very different than playing for Phil Woods on the alto saxophone. So playing with Sandy Stewart is going to be a lot different than playing with Kurt Elling. So there’s ranges, and points of view, and attitudes: all of those things certainly teach you. And they would surprise you all the time. Carmen McRae could come in on any part of the bar, or any beat. There was nobody like her. And of course Sarah was the ultimate virtuoso.

“When I was in my early teens, I was already thinking like a singer.”

You know, a part of it is I grew up listening to those records a lot—I gravitated towards great singers. When I was very young, when I was in my early teens, I was listening to Carmen McRae and Sarah Vaughan and I loved their music so much, all different periods, so that I was already thinking like a singer, in a sense.

BH In an article you wrote a while back for Jazz Times you said that singers and their accompanists are like dancing partners…

BC Well that’s right, you know—the singer is perhaps a little bit more the leader, but not always. Sometimes you lead, I follow, sometimes I lead, you follow. And we react to each other, and two become one.

BH The great pianist Jimmy Rowles, whom I know you admire a lot, talked about accompanying and he talked about the need to subdue yourself, as he put it. He said, “If you don’t subdue yourself, the listener is going to get confused because the piano part will be competing for the listener’s attention.”

BC I can’t say I feel exactly the same way, because I don’t feel like I ever feel like I would want to compete for attention with anyone that I’m playing with. And I don’t feel like I’m doing anything but what seems right for the music. I never feel like I’m subduing myself with a singer, actually. I know what Rowles is talking about, and of course I respect him as high as any giant who’s ever been in this music. But I feel like if you’re doing what’s right for the music, then you are expressing yourself, exactly, perfectly. I’m sure that’s exactly what he’s saying too; I think he was talking about how maybe there are musicians who want to be the center of attention all the time. But that’s not my style, I wouldn’t even want that in my own band. I love the musicians who play for the entire group. You listen to the way that Teddy Wilson played, or Miles Davis played, or Gerry Mulligan played: that turns me on, that way of thinking.

“Working with a singer, you’re that much more alive to every moment, because everything you do matters in such a focused way.”

So working with a singer, you become a part of this beautiful collaboration where nothing is subdued, in fact, you’re that much more alive to every moment, because everything you do matters in such a focused way. The melody takes on its prime importance, which it has anyway. And the words, the story, the layers underneath the words. Sometimes a color on a harmony or a value of harmony, maybe two notes as opposed to three, as opposed to four, five, six or seven…that tells a story too. It creates the layers. It creates something that is not there necessarily on the face of the lyric but might be underneath it. Something like a great underscore does for a film: it might tell you something about what is really happening while you’re watching a scene. All those things.

BH Let’s talk a little bit more about Jimmy Rowles as an accompanist. Carmen McRae said that Jimmy was “the guy every girl singer in her right mind would like to work with.”

BC Well, Jimmy loved the melody. He loved the words. And he cared about the song, first and foremost. Also, Jimmy just never overplayed. He was never going to play something that focused your attention onto anything but the feeling of the music—he was all feeling. He came from Teddy Wilson and Duke Ellington but he had his own harmonic way of approaching things that was real genius. He was like a great painter who uses just exactly what’s necessary to fill in the picture.

BH And no one else sounds like him…

BC That’s true. That’s what a jazz musician wants. Not even wants, but what other goal is there, other than to be yourself? That’s what we celebrate: when we talk about someone we love it’s always, “Oh, I love the way that person plays,” you don’t say, “Oh I love the way he plays because I can hear this other person in his playing.”

BH Jimmy Rowles said this about accompanying: He said, “Don’t play too much, don’t play too loud, and don’t play the melody.”

BC (Laughs) Well, I think all of those things are good but none of them are rules. Sometimes it might be the right time to play too much. Or too loud. Or the melody. So I agree with half of that.

.

A musical interlude: “I Thought About You” with Sandy Stewart and Bill Charlap, from the 2013 album Something to Remember

.

.

BH You also commented in that Jazz Times article about the importance of creating introductions to set up the song, and of creating endings, too.

BC One of the great things that the greatest arrangers did, from Duke Ellington, to Bill Finegan, Nelson Riddle, and Slide Hampton—introductions. Hank Jones and Tommy Flanagan would improvise the most glorious set-ups for the songs that would have elements of surprise but would also absolutely set the tone. I remember feeling very complimented by Slide Hampton once on horn arrangements I had written. He said the introduction and the ending were great, and that’s so important. And that he liked that meant a lot to me. And it solidified in my mind how important those things are. So yes, those are key elements. Just listen to Hank Jones play an introduction on “Nostalgia” on the great Lee Morgan record, or to Duke Jordan’s lovely intro on “Embraceable You” by Charlie Parker.

All my favorite piano players are great accompanists. Tommy Flanagan, Hank Jones, Bill Evans, Jimmy Rowles…Oscar Peterson was a great accompanist: Imagine those things with Ella and Louis without Oscar Peterson in there. And with all the piano he could play, still, he knew what to do.

BH So what are a few of your favorite singer/accompanist combinations?

BC Well, Ellis Larkins and Ella Fitzgerald, that’s a magic one; the work that Bill Evans did with Tony Bennett is stellar, there’s nothing like it; Jimmy Rowles and anybody he worked with; Tommy Flanagan and Ella. My favorite accompanist of all, though, is Shirley Horn playing for Shirley Horn! That’s, I think, about the paragon of perfection in accompanists for a singer.

BH She talked once about how nobody else could accompany her, that she was in fact her own best accompanist.

BC Well, she was right about that. Although she did give me a chance on the record I did of Hoagy Carmichael songs, and I was very honored by that, to accompany her on “Stardust.”

.

A musical interlude: “Stardust” by Bill Charlap and Shirley Horn, with Peter Washington, bass, Kenny Washington, drums ; from the 2002 album Stardust

.

BH And how about Blossom Dearie as a singer and accompanist?

BC Blossom brought so many great songs and was such a uniquely original performer. She was wonderful, what else can I say? And had such great repertoire.

BH Bill Evans said some very favorable things about her piano playing. He was impressed.

BC Oh yeah. Well that’s saying something. That’s rather like saying Bach likes your counterpoint. (Laughter)

BH So in all the various accompanying that you’ve been doing, are there some that stand out for you, that you’re particularly proud of?

BC Well, the stuff with my mom is at the top, that’s the top. And playing for Carol Sloane is absolutely great. She was so easy to play for—a natural in every kind of way. I also love Ernie Andrews and Freddy Cole, two other fantastic singers I’m just crazy about, and I love to play for either of them.

BH And you’ve had some wonderful collaborations with Tony Bennett, on the Jerome Kern album…

BC Yes, well Tony’s wonderful and I thought that the Kern record was really very successful. There are some very beautiful moments on there, some special moments where he does one of those particularly special things that he does where he can almost sing operatically in terms of getting the point across, and then get quiet and intimate within the same performance. Tony’s always reacting to what he’s hearing around him, so in that sense he’s a jazz man. He’s a painter too, so he hears the colors; he will hear what’s in the chord and he has an incredible gift of natural taste to find the signature notes that illuminate the songs and put his signature on them.

I love the things on there, too, with Renee [pianist Renee Rosnes, Bill’s wife]. There are four tracks that are two pianos. And with all that, 20 fingers and 176 keys, it’s never cluttered because Renee is such a wonderful listener and there’s such a collaboration there, that it really became sort of an orchestral approach. She is absolutely as good as it gets.

BH Your rendition of “Long Ago & Far Away” on that album is amazing. It’s you and Renee with Tony, and there’s such evident joy in the inventions you’re involved with there.

BC I love that one, and I especially love at the end when Tony sings, “Just a moment and I knew that what I longed for,” and on the note “for” he reaches up for this high A natural and he just nails it. It only happened once, Tony is very extemporaneous, and it was a magical moment. I remember Renee and I looked at each other and our eyes bugged out. It almost sounds as if it was edited or something but it isn’t. He just nailed it. Bang! It was beautiful.

.

A musical interlude: “Long Ago & Far Away” with Tony Bennett with Bill Charlap & Renee Rosnes from the 2015 album The Silver Lining: The Songs of Jerome Kern

.

.

BH In listening to your playing on that album I was especially struck by your use of space, particularly on “Yesterdays.”

BC Everything that you play is against the canvas, and without the canvas it’s nothing. The canvas, the space, the sound of silence, is also one of the characters. A drummer who’s playing perfect time is only playing perfect time against the silences: you must use that ‘cause it’s another color in your palette. So you play the space. Apparently [saxophonist] Lee Konitz once stood up to play a solo but never played a note and sat back down. (Laughter)

BH Yes, I heard about that, I believe Lee referred to that afterwards as “a perfect solo.” (Laughter) I read recently that Lee’s motto was “Listen is an anagram for silent.”

BC You gotta love him.

BH When you’re working in the studio with someone like Tony, how do you come up with the routine for a piece, how do you work out the arrangements?

BC On that album it was very simple, we both work very fast, and he’d have a conception very quickly. First it was, ‘What songs do you want to sing?’ ‘Start singing it, let’s find a key.’ ‘I thought the approach tempo-wise could be like this.’ It was very collaborative.

BH In working with Tony, how much of his earlier, monumental collaboration with Bill Evans was a model or an inspiration for you?

BC Anything Bill Evans played has been a model throughout my life. But of course I’m not Bill Evans, and it would be awful to try to be somebody else. And at the same time those are monumental recordings and were monumental for me growing up. My teacher Jack Reilly, with whom I studied during high school, a great pianist and composer, gave me a cassette of Bill Evans and Tony Bennett. So those recordings certainly inform my way of playing with Tony, and perhaps more so on “All the Things You Are” than anything else on the album.

BH Are there any other aspects of the art of accompany you’d like to comment on?

BC I can only reiterate: knowing the song and knowing the lyrics, and being completely cognizant of the melody and the lyrics, and having them be paramount, is what is the most important thing. In playing a song, in accompanying a singer, and in the entire aesthetic of the Songbook. If you have those things as your paradigm and you understand the harmonic structure of the piece, then you’ve got everything you need to be a great accompanist.

.

A musical interlude: “A Ghost of a Chance” by Sandy Stewart and Bill Charlap from the 2013 album, Something to Remember

.

.

___

.

.

Sandy Stewart, with Bill Charlap

.

A Conversation With Sandy Stewart

.

BH Sandy, you’ve worked with some remarkable accompanists over the years…

SS Well, yes, in fact I have been spoiled rotten ever since starting in show business as a young girl—to a point that it’s ridiculous. The gentlemen who have accompanied me over the many years that I’ve been doing this range from Bernie Leighton to Erroll Garner to Mike Renzi, Joe Harnell, Frank Owens, Burt Bacharach, and it just goes on and on. And when I started in New York City at the age of sixteen and was accompanied right out of the gate on a live TV show by Bernie Leighton, I thought, quite naively, that anybody who accompanies a singer definitely knows how to do it, automatically. Ah youth! (Laughter) When I was seventeen I was on another live TV show at NBC, a morning jazz show, which I did before I went to my high school classes. The first day I walked into the studio, and the musicians were as follows: Dick Hyman on piano, Eddie Safranski on bass, Don Lamond on drums and Mundell Lowe on guitar. They had apparently all been talking about me before I got there, and had been imagining this sexy jazz singer who was coming to the studio. And I walked in wearing a pink and white gingham dress with a ponytail and my school books, and Mundell Lowe looked over at Safranski and said, “Forget it, Eddie—jail bait!” (Laughter) For years afterwards, whenever I would run into Mundell, he would say, “How you doin’ jail bait?”

Much later, in the 1980’s, Dick Hyman and I recorded together on an album of Jerome Kern songs. And then I worked with Mike Renzi, who is a fabulous accompanist, and was for many years my go-to guy—until I gave birth to Bill! (Laughs)

BH Although it took Bill a little while to get up to speed…

SS A little while, yes. (Laughs) We started to work together and try things out when he was, I guess, 18 or 19. And at that time, Gerry Mulligan had hired him, so he certainly knew his stuff at a very young age. It was also important that he knew the lyrics, because when an accompanist knows a lyric it takes you where you want to go emotionally.

So I was spoiled early on, because everybody who accompanied me in New York knew what they were doing, and anticipated where I was going vocally. But when I went on the road and sometimes had to use a local pianist, it wasn’t always at that high level.

“You don’t want to overplay when you’re playing for a singer.”

BH So in addition to an accompanist having a deep understanding of the lyrics, the meaning of the song, the drama of the song, what are the musical attributes that a great accompanist needs to have?

SS Well, the first thing is not to play the melody along with the singer. And there are accompanists who tend to do that, and as a singer you don’t want that to happen. It takes away from your performance, it’s a major distraction. And Bill and Mike [Renzi] always play the right changes. And it’s a wonderful thing, it’s like having a cushion, knowing that wherever you go emotionally or vocally, they’re there right with you. And that’s very important. You don’t want to overplay when you’re playing for a singer.

BH It seems to me that the singer-accompanist relationship is a very close, intimate one…

SS Absolutely.

BH And it must be even that much more so when the accompanist is your son. Can you tell me about that relationship?

SS Oh, gosh. It’s quite unusual and quite marvelous. We’re totally on the same wavelength, all the time, and on the same page insofar as how we want to approach a song. People will say to me, “When the two of you are working together, it’s like the umbilical cord was never cut.” I think perhaps we captured some of that feeling on a couple of our recordings.

I never expected this to ever happen in my life. But he showed interest in the piano at a very, very young age—when he was three he’d walk up to the piano and play melodies, one finger at a time, no banging the keyboard like young kids typically do. And I looked at Moose one day and said, “I think we have a musician on our hands here.” And he said, “I think so.” But he was always fascinated by the piano. That was the love of his life, growing up. And now the love of his life is a great pianist, Renee Rosnes.

BH She is indeed.

SS Oh, she is remarkable. First of all, she’s a remarkable human being, a great composer, a great arranger, a good cook—I mean, Bill’s got it all with her! And Renee has accompanied me several times, and she’s a wonderful accompanist, too, very sensitive. And when working with Bill, I just need to glance over at him, and he knows intuitively what I’m going to do and where I’m going to go. Emotionally, more than anything it’s a unique thing. It’s almost like singing a capella, except I have this amazing musicality with me. It’s all one.

BH In listening to “A Ghost of a Chance” with you and Bill from your Something to Remember album, I was thinking, “Boy, his fills are just perfect behind you…”

SS They are!

BH But then I realized, wait, it’s more than just ‘fills’—it’s really a sort of mutual creation that’s going on between the two of you, it’s really quite marvelous.

SS Well, thank you, Bob, I appreciate that very much. I just love working with him. It’s very special for both of us, and hopefully for the people that are there to listen.

BH I think Bill’s approach is very minimalist as an accompanist…

SS Very. Very minimal, BUT you know he’s there without a doubt. He’s a singer’s dream. Every singer I know says, “You’re so lucky. I wish I could work with him.” I say, “Well, I’m not getting into that!” (Laughs)

BH One of the most emotionally moving, even wrenching, of the ballads you two have done, is the Cole Porter song, “After You.”

SS I first sang that, with Bill on piano, at the Algonquin when we were doing a yearly stint there. And I remember the first time we did it, in rehearsal, we both burst into tears. We just get very emotional when we do certain things like that.

.

A musical interlude: “After You” Sandy Stewart and Bill Charlap from the 2005 album Love Is Here to Stay

.

BH One of Moose Charlap’s most beautiful songs is, “Here I Am in Love Again,” which you have recorded with Bill. That must be a very special to be working with your son and recording a song by his dad and your late husband…

SS Oh, absolutely. I love to do Moose’s music, of course.

BH I can only imagine what Moose would think, seeing this evolution…

SS You know, that’s the tragedy of life, when someone so talented and so young, and that goes through my mind on a daily basis. That he’s not here to see Bill’s success, with Bill as not only a great musician but a wonderful human being. It’s just tragic that Moose had to leave the planet so young. Bill was only seven years old when Moose passed. We talk about that; Bill will say, “Oh, I wish dad was here to see this.” That’s life, what’re you going to do?

BH Yeah, sadly, that’s life…and that must have been such a tragic loss for you and for Bill, who was still at such a young age.

SS Oh, it was devastating. It still is. It still is. That doesn’t go away. But Moose’s music is still here. Onward and upward. And Bill and Renee are carrying the torch, and it’s wonderful. And I’m certainly glad to be a part of this whole thing, that’s for sure. And I make great fried chicken, just ask him, he’ll tell you. (Laughter) Forget about the American Songbook….it’s all about the fried chicken.

.

Listen to Bill Charlap and Sandy Stewart on Moose Charlap’s song, “Here I Am in Love Again,” from the 2005 album, Love Is Here To Stay

.

.

___

.

.

Bob Hecht frequently contributes his essays and personal stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. He has a long history of producing and hosting jazz radio programs; his former podcast series, The Joys of Jazz, was the 2019 Silver Medal winner in the New York Festivals Radio Awards.

.

.

We are grateful to Carol Friedman for granting use of her photographs of Bill Charlap and Sandy Stewart.

Carol photographs and designs image campaigns for celebrated and emerging figures in the art, music and media worlds. Her classic portraits elegantly capture the allure, depth and idiosyncratic style of her iconic subjects. An avowed music lover, her images of jazz, soul and classical recording artists have been widely published and may be seen on hundreds of album and CD covers.

To visit her website, click here.

To read a 2019 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with Ms. Friedman, click here

.

.

“Jazz Duet II” by Leo Meiersdorff is published with the gracious consent of the Meiersdorff Estate. To visit Meiersdorff’s website and view much more of his work, click here. The original is currently in the collection of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, LA. Click here to visit their website.

.

___

.

.

.

“The Art of Accompanying” is a 50 song playlist featuring countless great performances, including by Shirley Horn, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Frank Sinatra, Mel Torme, and many others.

.

.

.

“Art of Accompanying” playlist credits

.

“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” Cécile McLorin Salvant: vocals; Aaron Diehl: piano; Rodney Whitaker: double bass; Herlin Riley: drums

“My One and Only” Ella Fitgerald, Ellis Larkin (p)

“Darn That Dream” Sarah Vaughan, Ronnell Bright (p), Freddie Green (g), Richard Davis (b), Sonny Payne (d), Frank Foster (ts), Snooky Young or Joe Newman (tpt)

Come Dance With Me” Shirley Horn (vcl, piano), Charles Ables (b), Steve Williams (d), 1990

“Lucky To Be Me” Monica Zetterlund, Bill Evans (p), Chuck Israels, (b), Larry Bunker (d), 1964

“My Ship” Mark Murphy, Francy Boland on piano, Jimmy Woode on bass, Kenny Clarke (d), 1967

“I Remember You” Jazzmeia Horn, pianist Victor Gould, bassist Ben Williams and drummer/percussionist Jerome Jennings

“The Night We Called It Day” Carol Sloane, Bill Charlap (p), Sean Smith (b), Ron Vincent (d), Frank Wess (ts), 2014

“Once In While” Freddy Cole, Bill Charlap (p), Peter Washington (b), Kenny Washington (d), 2006

“Porgy” Billie Holiday, Bobby Tucker (p) Mundell Lowe (g) John Levy (b) Denzil Best (d), 1948

“When Lights Are Low” Roberta Gambarini, Hank Jones (p), 2007

“Something To Live For” Carmen McRae, Billy Strayhorn (p)

“Nancy With the Laughing Face” Kurt Elling, Laurence Hobgood (p),

Clark Sommers: bass

Ulysses Owens: drums

Ernie Watts: Tenor Saxophone

“Naturally” Veronica Swift, Benny Green, flutist Anne Drummond, bassist David Wong, drummer Kenny Washington, and Josh Jones on percussion, 2018

“Skylark” Bill Henderson, Tommy Flanagan (p), Freddie Green, guitar; Milt Hinton, bass; Elvin Jones, drums; 1960

“As Long As I Live” Anita O’Day, Paul Smith (p), Barney Kessel (g), Joe Mondragon (b), Alvin Stoller (d), 1955

“The Shadow of Your Smile” Tony Bennett, Jimmy Rowles (p), Johnny Mandel (arranger), 1965

“There Will Never Be Another You” Nancy King, Fred Hersch (p)

“My Ideal” Freddy Cole, Bill Charlap (p), Peter Washington(b), Kenny Washington (d)

“Stardust” Shirley Horn, Bill Charlap (p), Peter Washington(b), Kenny Washington (d)

“They Say It’s Spring” Blossom Dearie (vcl, p), Ray Brown (b), Jo Jones (d), 1956

“One For My Baby” Frank Sinatra , Bill Miller (p)

“How Deep Is the Ocean” Dena DeRose (vcl, p), Martin Wind (b), Matt Wilson (d)

“Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most” Irene Kral, Alan Broadbent (p)

“Hi-Fly” Mel Torme, George Shearing (p), Don Thompson (b), 1997

“Softly As in a Morning Sunrise” Paula West, George Mesterhazy (p), Ed Cherry: guitar; Barak Mori: bass; Jerome Jennings: drums, 2012

“It Amazes Me” Tony Bennett, Ralph Sharon (p)

“Something I Dreamed Last Night” Veronica Swift, bassist David Wong, drummer Kenny Washington, and Josh Jones on percussion, 2018

“My Man” Ella Fitzgerald, Tommy Flanagan (p), Keter Betts – Bass; Bobby Durham – Drums, 1977

“Nobody Else But Me” Sandy Stewart, Dick Hyman (p), 1985

“But Beautiful” Tony Bennett, Bill Evans

“A Sleepin ‘ Bee” Nancy Wilson, Joe Zawinul (p), Sam Jones (b), Louis Hayes (d), Nat & Cannonball Adderley, 1961

“Ghost of Yesterday” Carmen McRae, George Shearing (p)

“You Say You Care” Rebecca Kilgore, Randy Porter (p), Scott Steed (b), Neil Masson (d)

“Trouble Is a Man” Cecile McLorin Salvant, Sullivan Fortner (p)

“Sweet Lorraine” Gregory Porter, Chip Crawford – piano, Tivon Pennicott – sax

Jahmal Nichols – bass, Emanuel Harrold – drums, Vince Mendoza – conductor

The London Studio Orchestra

“Lover Man” Carmen McRae, Norman Simmons (p), Mundell Lowe (g), Bob Cranshaw (b), Walter Perkins (d), 1961

“Exactly Like You” Helen Humes, Gerald Wiggins (p), Ed Thigpen / drums, Gerard Badini / tenor sax, Major Holley/ bass

“Turn Out the Stars” Meredith d’Ambrosio (vcl & p)

“Baltimore Oriole” Sheila Jordan, Steve Swallow (b), Denzil Best (d)

“Sunday” Carmen McRae, Jimmy Rowles (p), Joe Pass (g), Chuck Domanico (b), Cuck Flores (d), 1961

“Angel Eyes” Anita O’Day, Merrill Hoover (p), George Morrow (b), John Poole (d), 1981

“Some Other Time” (Bernstein) Monica Zetterlund, Bill Evans (p), Chuck Israels, (b), Larry Bunker (d), 1964

“Some Other Time” (Styne) Betty Carter, Harold Mabern (p), Bob Cranshaw (b), Roy McCurdy (d), 1965

“Soon” Ella Fitzgerald, Ellis Larkin

“Detour Ahead” Tierney Sutton, pianist Christian Jacob, bassist Trey Henry, and drummer Ray Brinker

“This Time the Dream’s On Me” Mel Torme, George Shesring (p), Din Thompson (b)

“Lullaby of Birdland” Chris Connor, Ellis Larkin (p)

“For All We Know” Janis Siegel, Fred Hersch (p)

“I’m All Smiles” Diane Reeves, Trumpet: Nicholas Payton, Piano: Peter Martin, Bass: Ruben Rogers, Drums: Gregory Hutchinson

Guitar: Romero Lubambo

“The Nearness of You” Nancy Wilson, George Shearing (p), Dick Garcia (g), Walter Chiaisson (vibes), Ralph Pena (b), Vernell Fournier (d), Armando Peraza (percussion), 1961

“Willow Weep for Me” Sheila Jordan, Barry Galbraith (g), Steve Swallow(b), Denzil Best (d)

“You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To” Helen Merrill, Kenny Barron (p), Rufus Reid (b), Victor Lewis (d), Wallace Roney, Roy Hargrove & Lew Soloff (tpts), 1994

.

.