.

.

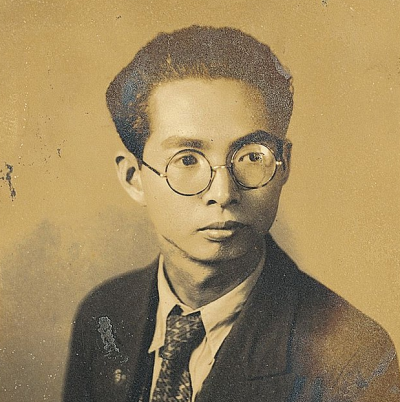

Photo: Brian McMillen

Elvin Jones at Keystone Korner, San Francisco CA 4/22/80

.

___

.

.

The Elvin Jones Standard

by Evan Nass

.

___

.

…..Elvin Ray Jones (September 9, 1927–September 9, 2004) was drawn to the drums at just two years of age, performing and recording up until the last few years of his life. He was the go-to drummer on many of the great jazz recordings that helped change the face of music, including John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, Wayne Shorter’s Juju, and McCoy Tyner’s The Real McCoy. His style is unique, expressive, bombastic, heavy and rolling. He became one of the most famous drummers, making vast contributions to the hard bop and post-bop jazz movements. He had great influence on all the jazz musicians he played with, but more importantly, they influenced him.

…..Acclaimed drummer Mark Guiliana once told me, “I think about him every time I sit down and play. Elvin is absolutely one of my heroes and what he’s done for the instrument and the drum set is incredibly inspiring to drummers every day. The things he played technically were fascinating, but it was more the spirit with which he played.”

…..Mark Shim, a tenor saxophonist who performed with Elvin for approximately two years told me; “Elvin first saw me play with Betty Carter in 1997 at the Blue Note . . . and we played ‘Body and Soul.’ Elvin shook my hand and told me that I sounded good. Four years later Keiko [Elvin’s wife and personal manager] got in contact with me and asked if I was the one who played ‘Body and Soul’ at the Blue Note!” The next thing he knew, Mark found himself performing with Elvin.

…..“He [Elvin] and Betty Carter come from the same school of nurturing future musicians and passing on wisdom to younger musicians,” Shim said to me. “Within this type of art form, jazz in particular has its history and foundation and roots in embracing community and learning from each other. Obviously, I’ve learned a great deal just being on the stage with him but now that I’m getting older, I’m always learning on the bandstand. I wouldn’t be surprised if Elvin felt like he learned from the sidemen in his bands as well.”

…..Shim’s thoughts on Elvin got me curious about the nature of his later releases. Elvin was prolific and certainly at a stage in his career where he could have played with anyone in the jazz world.

…..From 1970 until his death, Elvin released approximately 39 albums and seemingly hired younger and younger musicians as he got older. He released albums like Genesis (1971) with its spacey feel, and Merry-Go-Round (1972), with the pop/soul influenced tune “‘Round Town.” In 1975, Elvin’s quartet released Mr. Thunder, which made extensive use of Roland Prince’s forward-thinking progressive guitar comping and tones that bordered on distortion. Tracks like “Three Card Molly” included the 25-year-old Swedish percussionist Sjunne Ferger, thereby outsourcing even his own rhythm section to younger drummers. In 1975, he released On the Mountain that featured upcoming musicians — keyboardist Jan Hammer and bassist Gene Perla.

.

Listen to “Thorn of a White Rose”

…..I recently discussed Elvin’s later discography with Ed Gavitt, guitarist of Secret Mall, and how the album On the Mountain seemed to veer considerably from prior standard Elvin recordings. The track “Thorn of the White Rose” is an example. What was so interesting about On the Mountain was how “un-Elvin” it was. It deviated drastically from the classic masterpieces we all know. Released in 1975, the album was a first step into the then budding fusion era of jazz. “Thorn of the White Rose” ventures into the heavy bass of Gene Perla with Elvin slamming down on the cymbals like an early heavy rock drummer. Although his drumming style does not perfectly match the manicured fusion drumming of Steve Gadd, Danny Gottlieb, and other benchmark fusion drummers, it does express a desire to embrace the new potentialities rather than shy away from change. His percussive strikes cut through with a rock feel, powerful yet soulful, pounding polyrhythms against a backdrop of synth and sanitized fusion. Needless to say, this album was not a breakout success and went largely ignored by those beyond his fan base. However, it did pique our interest about Elvin’s mindset. He was seemingly more inclined to play with younger musicians, even if it meant a transition he was not yet particularly known for, or even necessarily suited.

…..When On the Mountain was released, Elvin was 48 years old. The album included only two personnel, Hammer and Perla, who at the time of the recording were 27 and 35 respectively—an average of 17 years younger than Elvin. Elvin’s average age throughout all his releases (from the date of his first recording as a lead, to the date of his last recording as a lead) was 49.8. The average age of his personnel, a mere 36.3; a 13.5-year age gap between himself as a leader and his co-musicians. The numbers diverge even greater if you include the latter half of his recording career. From 1975 until his death, his average recording age was 59.6 years, and his personnel was 38.8-years-old—a gap of 20.85 years between them. In other words, as he grew older, his use of younger musicians increased by a 6.8-year disparity.

…..We can further explore Elvin’s outlook by comparing him to similar artists of his generation such as Charles Mingus, Ahmad Jamal, Horace Silver, Hank Jones (Elvin’s brother), McCoy Tyner and Freddie Hubbard, who all released a similar number of albums as him, lived to a similar age, and were stylistically alike. None of these artists came close to the 20+ year age gap that Elvin had with his co-musicians (Ahmad Jamal had an age gap of merely four months on average).

…..Shim recalled that by the early 2000’s, “Elvin always closed every set with Duke Ellington’s ‘It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing’. But Elvin’s version was so modern and fresh. He played it without making it sound cheesy, made it so personal that I eventually looked forward to playing it! And he made everyone sound good. Elvin wasn’t just a great player; great players sound great, but legends make the whole band sound great.” In Elvin’s world, the band often included those much younger musicians with less experience.

…..Despite being a keystone in the hard bop era, Elvin went on to absorb, advance and change, and he did so while embracing younger musicians. David Freeman, drummer, percussionist and adjunct professor of Jazz History with the Department of Media, Communications and Visual Arts at Pace University, articulated the magnetism Elvin had perfectly. “Musicians in the non-commercial music pursuit want to find their sound and their feel and their voice—typically making money is secondary. Elvin’s sound and his technique is so easily felt by musicians who aren’t necessarily interested in the theory or the ingredients that make up technical composition, but in exploring a musician who embraced and pursued what made them unique.” Freeman went on to tell a story about how bandleaders who hired Elvin would hand him their charts upon his arrival, but Elvin would throw them aside because he was more focused on his sound and his feel, which is what he did best.

…..Perhaps this is why Elvin didn’t get the gig when he famously auditioned for Benny Goodman’s band in 1955, but it is what made his playing and compositions so universally accessible. His music drew in the younger musician with unquantifiable acceptance to explore that which you want to be, not what is expected. Perhaps this is what Coltrane saw deep within Elvin’s playing and what made him a perfect match for the famous Quartet.

…..“I went to go see him at the Blue Note in 1998,” Freeman recalls. “I was very early, and I saw Elvin pull up in his car and he got out with Keiko and they went inside the club…I went in and went upstairs with my Love Supreme album to get him to sign it. I’m hanging out there and his wife asks me to come in. I couldn’t believe it. And there is Elvin and he’s enormous and I say ‘hi’ and tell him that I play drums. He signed the record and shook my hand, so warm and so loving, and he didn’t even rush me out. It was just incredible. He had such an energy.”

…..Elvin always used the kit to enhance the musicians and the band as a cohesive unit. Once, drummer Bill Larkin complained about a sax player that kept reverting to 4/4 regardless of time signature. When he expressed his frustration, Elvin responded, “So? What if he changed time every other measure? Follow him. Follow him into hell and come back with smiles on your faces.” Elvin’s passion was following the musician regardless of their age or experience. He did what was best for the music, and ultimately, that outlook sculpted him more than anything else. Elvin thought the greatest contribution to American music was taking the conductor and placing him in the band itself. The very real belief in the democratization of music ironically elevated Elvin Jones above the rest.

…..In an era today where many younger musicians feel an age-gap divide, perhaps we can look once again to the legend for advice on how to shape the music we create, and the person we are to become. Elvin Jones clearly did not require a specific pedigree of his album personnel, he simply wanted to express what he created. His legacy as legend is well-deserved.

Interested readers can check out the Elvin Jones Songbook on Spotify, which contains over 33 hours of his music, all as leader.

.

.

“Round Town”

.

“Three Card Molly”

.

.

“It Don’t Mean a Thing (If it Ain’t Got That Swing)”

.

.

_____

.

.

.

Evan Nass is an attorney and the managing partner at Nass Roper & Levin, PC in New York City. He is a drummer, jazz fan, and in particular, Elvin Jones enthusiast. He worked in the music industry both in the recording and record label ends of the spectrum. Over the years he had the pleasure of being able to work for musicians such as Joe Satriani, Steve Vai and Keith Richards. He is a professor of argumentation and inquiry and resides in New Jersey.

.

.

.

Brian McMillen Jazz Photography

.

.

.