.

.

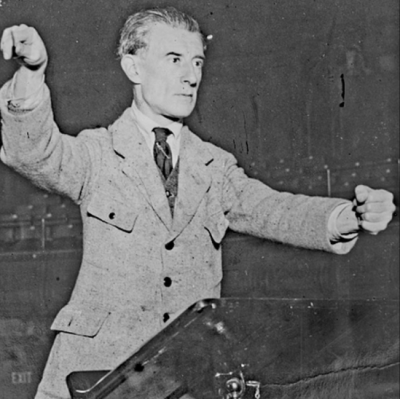

photo by Steve Schapiro, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Publicity photo of American jazz pianist Bill Evans in 1961. Photographed by Steve Schapiro for Riverside Records

.

.

___

.

.

The Compositional Genius of Bill Evans

—A Brief Overview & Playlist—

by Bob Hecht

.

…..When Riverside Records released Bill Evans’ second album as a leader in 1959, they titled it—unknown to Evans in advance—Everybody Digs Bill Evans, and filled the cover with laudatory quotations from several high-ranking jazz artists, including Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley and George Shearing. Evans was reportedly upset by it, and cracked, “Why didn’t you get a quote from my mother?!”

…..I have been a fan of Evans’ unique approach to playing jazz piano from the time of that release, and while it may be true that not everybody digs Bill Evans, I have seen over the years that for those jazz fans who do dig him, they really dig him, dig him very deeply, and feel a profound emotional/spiritual connection with his music. Most of that is the result, I believe, of his extremely personal, vulnerable, lyrical style. The man was a poet of the piano.

…..The contours of his career, personal life and ultimate self-destruction have been well documented, and he is rightly respected, and revered, as a giant of the piano.

…..However, in addition to being the marvelous pianist he was, he was also a remarkable composer. And while much has been written about his playing, there has been, I believe, insufficient focus on his compositions and his composing style. This is in spite of his having written some fifty tunes, many of which have been recorded by other jazz musicians and have become jazz standards. (“Waltz for Debby” is of course one of the best-known.) True, Evans was not a prolific composer, and did not reportedly think of himself as a dedicated, full-time composer—rather he considered himself a jazz player who sometimes composed. Yet his compositions are among the most original in jazz, marked by sensitive, beautiful melodies with rich harmonies owing no small debt to his appreciation of classical composers such as Bach, Chopin, Scriabin, Ravel and Debussy.

…..As Jack Reilly, the noted pianist, composer and Evans scholar has observed, “Besides his amazing playing, Bill Evans’ compositional legacy is set for centuries. Like all the masters, Wagner, Chopin, Rachmaninoff, et al, his music is timeless.”

…..Evans did study composition, and took very seriously his own efforts in that arena. He once told Brian Priestly in an interview, “I’ve always had a compositional ambition and desire. So I would like to get busier writing.” He was known for giving new life to old or overlooked standards by the composers of the “Great American Songbook,” and he looked to them for inspiration in his own composing. “I read somewhere,” Evans once said, “that Gershwin had to write twelve bad tunes to get a good one. That gives me confidence.”

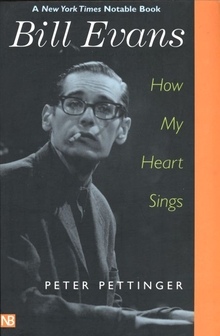

Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings, by Peter Pettinger [Yale University Press; 2002]

…..Pianist Warren Bernhardt, Evans’ pupil and friend, observed first-hand the seriousness of Bill’s approach to composing. As noted in Peter Pettinger’s indispensable biography, Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings, he consulted Bernhardt while writing a new composition dedicated to his son. “He would play it over and over in various keys and ask my opinion,” Bernhardt recalled. “Then he’d ask me to play it and transpose it and see what I thought. He really loved hearing these tunes of his over and over again.”

…..Pianist and educator Harold Danko has noted about Evans’ compositional output, “Nowhere can we learn more about the musical language of Bill Evans than from his own compositions.”

…..But composition for Evans was a means to an end—and that end was improvisation. His tunes, however rich and beautiful in and of themselves, were created to be springboards for “spontaneous composition,” the essence of jazz. He often referred to jazz as the art of playing “a minute’s worth of music in a minute!”

…..One particularly fascinating aspect of Evans’ compositions is how many of them had strong personal associations and dedications. For example, “Waltz for Debby” was written for his young niece, the daughter of his older brother Harry, with whom he was very close. “We Will Meet Again” was a tribute to his brother following Harry’s suicide; both “Song For Helen” and “One For Helen” were dedicated to his longtime manager Helen Keane, and “Peri’s Scope” was named in honor of a girlfriend, Peri Cousins. In his biography of Evans, Pettinger notes that when Cousins learned that Evans had recorded the tune named for her, she said, “It was a great feeling. I felt immortal.”

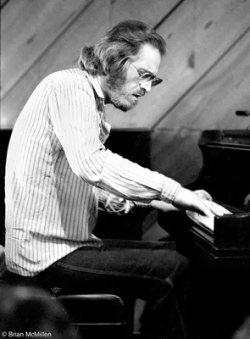

photo by Brian McMillen

Bill Evans at Montreux Jazz Festival, Switzerland;

July 13, 1978

…..Evans loved anagrams and created several extremely clever ones as titles to tunes dedicated to important people in his life. His extraordinary composition “Re: Person I Knew” was an anagram for the name of his Riverside Records producer, Orrin Keepnews; the brooding, emotionally-searing “N.Y.C’s No Lark” was dedicated to fellow pianist, friend and heroin addict Sonny Clark, following his death from an overdose; and “Yet Ne’er Broken” was written and named for his cocaine supplier Robert Kenney.

…..Other significant people in Evans’ life he honored in his compositions included girlfriend Ellaine Schultz, for whom he first wrote “There Came You.” About that tune, Bernhardt said, “This song is actually about that first moment he laid eyes on her; they fell immediately in love.” Tragically, Ellaine later committed suicide by throwing herself in the path of a New York subway train. Evans subsequently wrote “B Minor Waltz” in her memory.

…..In addition, among others, he composed “For Nenette” (aka “In April”) for his wife Nenette Zazarra, whom he married in 1973. Evans said about this tune that, “There was a danger of the melody being too sweet, and so I worked on this with a great deal of control and thought. The result, I hope, is a delicate balance of romanticism and discipline.”

…..“Maxine” was composed for his stepdaughter. “She’s happy, full of life,” Evans said. “The song has that spirit.” “Letter To Evan” was composed for his then four-year-old son Evan, born in 1975; and “Laurie” was created for his last girlfriend, Laurie Verchomin.

…..Bassist Chuck Israels, who played with Evans for several years in the 1960’s, observed in a 2014 All About Jazz interview, “Evans’ compositions are each constructed around one main idea. ‘Re: Person I Knew’ is built on a pedal point; ‘Walkin’ Up,’ on major chords and disjunct melodic motion; ‘Blue in Green,’ on doubling and redoubling of the tempo; and ‘Time Remembered,’ on melodic connection of seemingly unrelated harmonic areas.” Further, Israels noted that each of his compositions, “is so committed to a central idea that a program of Evans’ music is foolproof in its variety from composition to composition.”

…..Jack Reilly expressed the opinion that “Time Remembered” was Evans’ crowning compositional achievement, “because there are no active (dominant) harmonies in the progression. A miracle of major proportions! No one has achieved this, no one; no other composer from the 1600’s up to the 1980’s. That’s magic!”

…..Evans loved waltzes, and in addition to recording several by composer Earl Zindars (who wrote “How My Heart Sings”), he composed numerous 3/4 tunes himself, including “Very Early,” about which Pettinger wrote: “It exemplifies a fundamental lifelong characteristic—the application of logic to a creative musical process. It is a highly disciplined piece of writing.” And for his tune “34 Skidoo,” as Pettinger notes, “he also adopted Zindars’s idea of changing the time signature from three-time to four-time on the bridge.”

…..Most of Evans’ compositions were built on original structural harmony, rather than being based on existing chord changes of standards. A notable exception was “Five,” based on “I Got Rhythm.” But even then, Bill took creative license. As Pettinger notes, “The clever tune takes on the nature of an arithmetical puzzle. It is in four-time, but quintuplets occupy each of the first sixteen bars. It was, in short, as Bernhardt notes, “a bitch to play.”

…..According to Pettinger, Evans always carried with him a small composer’s notebook for writing down ideas. “A new tune was as likely to well up inside his imagination and be set down on a New York subway as it was at a piano.” Evans said that his “Show-Type Tune” was a case in point. “Songs usually required a lot of work later at the piano but this one came out nearly complete.”

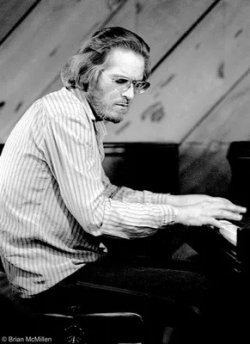

photos by Brian McMillen

.

Bill Evans at Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society, Half Moon Bay, CA; May 4, 1980

…..And then there was “Peace Piece.” One of Evans most unique and personal ‘compositions,’ this ruminative solo exploration was largely improvised in the studio, based on an ostinato figure he drew from the Bernstein classic, “Some Other Time.” (Some also believe it had a likely precursor in a Chopin piece.) Evans said of it, “Except for the bass figure, it was a complete improvisation. It’s completely free-form.” He never played it in public again.

…..Evans’ association with Miles Davis in the late fifties was an artistic high point for Evans, and one that gave him high visibility in the jazz world, particularly his involvement in the classic Kind of Blue recording. While Davis, infamous for stealing composer credits on tunes by others, claimed authorship of “Blue in Green,” it was in fact Evans’ creation. He explained, as Pettinger writes: “One day at Miles’ apartment, he wrote on some manuscript paper the symbols for G-minor and A-augmented. And he said, ‘What would you do with that?’ I didn’t really know, but I went home and wrote ‘Blue in Green.’” Similarly, Evans should have been credited as co-composer on “Flamenco Sketches” from that album, as it was built on the same pattern as his “Peace Piece.”

…..The reflective “Turn Out the Stars” remains one of his loveliest compositions and, as Pettinger notes, “was to endure and become arguably Evans’ second-greatest classic after “Waltz for Debby.”

…..His gentle ballad, “Sugar Plum” had a fascinating genesis. During the Evans-Jim Hall collaboration Intermodulation, on the tune “Angel Face,” Bill plays a sublimely lyrical phrase, which later caught the ear of songwriter John Court. Court “became obsessed” with this fragment, as Pettinger writes, “and created a lyric to accommodate several repetitions of the theme, thus delivery the pianist of a ‘freebie’ original. Evans was delighted.”

…..Two of his compositions were “finished” posthumously by pianist-singer Eliane Elias. “Here Is Something for You” was discovered on a cassette of Evans playing the new tune for bassist Marc Johnson shortly before Bill’s death in 1980. (Johnson was later to become Elias’ husband.) Elias wrote the lyrics to the tune. And “Evanesque” was developed from fragments of an unfinished Evans piece she discovered.

…..Over the decades, Evans’ compositions have captivated and challenged so many other jazz musicians. Pianist Bill Charlap, for example, said in a 2012 JazzWax interview: “Bill’s music was incredibly challenging and technical. As a composer, Bill was such a strong ‘architect’ that his ‘buildings’ never fall.”

…..To highlight his enduring compositional genius, I’ve assembled a Spotify playlist of almost all of his tunes. In most instances, it includes a couple of versions of each tune by Evans and the many others who have covered, and continue to cover, this unique repertoire. Consider it a kind of ‘endless loop’ tribute, honoring one of jazz’s finest composers.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Bob Hecht frequently contributes his essays, photographs, interviews, playlists and personal stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. He has a long history of producing and hosting jazz radio programs; his former podcast series, The Joys of Jazz, was the 2019 Silver Medal winner in the New York Festivals Radio Awards.

.

.

The photographer Brian McMillen has been documenting the jazz scene since the mid-1970’s. To view his work, visit his website by clicking here.

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to learn how to submit your work

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

One comments on ““The Compositional Genius of Bill Evans — A Brief Overview & Playlist,” by Bob Hecht”