.

.

“The Battle Scars of One Vinyl Record,” a story by Anita Overcash, was a short-listed entry in our recently concluded 56th Short Fiction Contest. It is published with the permission of the author.

.

.

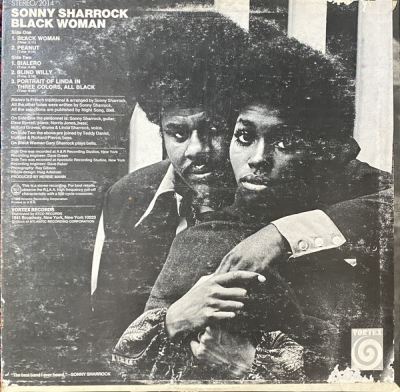

(Vortex/Rhino Atlantic)

The back cover of Sonny Sharrock’s 1969 album Black Woman

.

___

.

.

The Battle Scars of One Vinyl Record

By Anita Overcash

.

.

THE HUNT

Brent didn’t really go to Japan as a tourist. He went to Japan as a record hunter. The “Land of the Rising Sun” was known to house some of the best record stores for free jazz and that, my friends, was more important than any shrine, temple or giant Buddha statue. It was more important than devouring okonomiyaki (the Japanese pancake), slurping real ramen, or savoring the sweet anko pies. It was more important than weird cultural experiences that could have involved visits to maid bars, hedgehog cafes or quests to find the strangest vending machines. Instead, he’d gone to Japan to shop for records and make no mistake, Japan had him covered.

His itch for vinyl started in Kyoto and continued on to Matsumoto, finally climaxing in Tokyo. In Kyoto, he wandered into his first record store only to come out with an original pressing of Sonny Sharrock’s Black Woman. The album, released in 1969 on Vortex, was recorded in New York City and somehow made it to what’s dubbed as Japan’s “Eternal City.” Brent, who’d coveted the record for a while, imagined the record spinning loudly in an old shrine, the shrills of Linda Sharrock’s femme fatale expressions being absorbed by spirits like foreign candy.

Brent liked to imagine the journey of the records he added to his collection and he always bought them in person. Online orders were “cheating.” You had to find a record in the wild or die trying. Now how did Sonny Sharrock’s Black Woman come to be in Japan? A record filled with bells, keys, guitar and drums gone wild in true improvisational fashion. The journey of this particular vinyl was a mystery, but one he liked to entertain in detail. The intricacies would lead to an enlightenment of how a small scratch came to be on side two and how a small coffee stain came to be in the right hand corner of the record sleeve. As for the latter, he himself would never dare to have coffee or any other beverage near his records. He didn’t mind that someone else had done so prior to his ownership though. Those outer sleeve flaws gave the record character. They showed it had lived … and survived.

.

THE SCRATCH

When Kiyoshi wasn’t fishing, he was listening to music. He was tired a lot. He couldn’t listen to the music that he’d listened to years before back before the war. In fact, he avoided it at all costs. Listening to music from those days reminded him of a time when he was carefree, a time before his life unraveled, a time before bombs were dropped and lives turned upside down. Now he wanted a touch of chaos in his music. As he aged, it made him feel whole. He’d discovered free jazz and purchased some records, including Sonny Sharrock’s Black Woman, while on a trip to Berlin, Germany. The vinyl had touched his soul. It begged him to not just go with the flow, but to be the flow – a flow that at times was turbulent. That was so true to his village, which was subject to typhoons and other natural disasters annually.

Black Woman was released in the United States in 1969. How it made its way from the United States to Berlin, he’d never know but Kiyoshi was curious. He visited Berlin in 1972 and he fell in love with it’s gritty graffiti ridden street corners. Where he resided in Japan there was nothing of the sort and the nearby cities were clean and clear of defiance. No graffiti, no street art, and definitely no free jazz – or so he thought at the time. He was unaware of a small but growing number of Japanese avant-garde musicians that incorporated free jazz into their musical formations in Tokyo.

In Berlin, Kiyoshi stumbled upon a peculiar record that had a picture of a black man and woman on the cover. The photo was in black and white. More and more amazing music was coming to the country adding diversity, but it was a gradual process of vinyl invading the islands. Kiyoshi bought the album and brought it back to Japan. He’d played the hell out of it, listening to “Peanut,” a tune that starts off as a gnarly anthemic lull that’s driven into chaos with the spastic nature of keys, guitar and drums all alongside with the enchanted moaning of Linda Sharrock. Kiyoshi was always careful to use the best needles and the most technologically advanced record player, which he’d purchased on a trip to Tokyo, the land of any and every electronic gadget you could and would ever need. Listening to the record transformed him. It felt as if it were not of this world, the energy of free improv transforming his very ears. Of course, he had to keep the volume low. Elders in the village wouldn’t understand. Their river flowed in one direction – a direction of calm and comfort. One night, Kiyoshi fell asleep while listening to the record. He never thought that was possible but he’d had a long day of fishing and with the volume down he had dozed off listening to what brought him joy. He woke up just as the needle was penetrating the vinyl in a sharp ripping sound. It left a small scratch on side one, but it could barely be heard. Instead there was just an extra crackle swallowed by the jazz induced shock that the record’s raw sounds expelled.

.

THE STAIN

Berlin had risen from the ashes, but the ghosts of its past loomed overhead. Music had become Max’s coping mechanism. He picked up whatever psychedelic rock records he could find and when he learned that jazz went beyond its original smooth forefathers, he’d reached for any free jazz records he could find – the noisier, the better. The record of note, Sonny Sharrock’s Black Woman, he’d found at a shop in Berlin. It was actually a rental shop and he’d rented it. He just never returned it. The screaming, the instrumental chaos, he loved every second of it and supposed the underworld might merit such offerings. He could take it all at night with some shots of vodka or in the morning with a fresh cup-of-joe. On one occasion, he’d had a lady friend over who had woken to the instrumental anarchy. His latest conquest had walked into the room wearing whatever large T-shirt she’d found on the floor of his modest flat.

“What is this?” She’d asked with a sort of mix of alarm and intrigue.

“Ah,” Max had said. “Come closer.”

She’d walked closer to Max who was holding a cup of coffee in one hand and the album sleeve in the other. Once she got closer, he sat the album down on the table next to him and snatched her playfully so that she fell onto his lap.

“This is the new future of jazz. It too is rising from the ashes. It too is ready for change. Don’t you hear it crying out to you?”

At this point, he’d begun to tickle her so much that she playfully jerked thus causing Max to spill some of his coffee onto the record sleeve that sat adjacent to him on the table.

“Opps,” Max had noticed the stain but he didn’t care. Living in a country that had survived a war and was still building itself up from the rubble meant not caring so much about the little things. Every day bombs from the war were still being found, some even occasionally went off unexpectedly. It was tragic, but it became the new normal. Max had learned that life was fleeting and that there really were no guarantees. He was free and he liked his jazz the same way. He did not grab a handkerchief but instead he tickled his lady friend some more. He got up, turned off his record player – he was disciplined enough to never leave it on and unattended – and went back to the bedroom to make love to the lady before him. The stain seeped into the record sleeve causing a mere cosmetic flaw that would stand the test of time.

.

THE REFUGE

When Kiyoshi passed away, his granddaughter, Amira, didn’t know what to do with all his old records, but one thing was for sure, she didn’t want them. She appreciated that her grandfather had a passion for music and for experimental, avant-garde sounds, but she preferred classical music. It soothed her soul in a way that no other music could – especially not free jazz. She took his old records to a small shop in Kyoto. She watched as the shop owner looked through the records, his brows occasionally rising, his eyes looking at times as if they might be having some sort of optic orgasm. Afterwards, he looked at her dully as if he’d seen a ghost.

“Yes, we can take these. How about 5,000 yen?”

“Is that it?” asked Amira.

“7,000 yen. Final offer.” It wasn’t his final offer and Amira knew that but she didn’t feel like being in the shop any longer. There were too many people in the store flipping through records like flies at a picnic. The shop owner was inspecting a record at the time that appeared to be in good shape, but she noticed a stain on the outer sleeve. She wasn’t really sure what kind of shape all the records were in.

“That’s fine,” Amira said. “I know some of them probably aren’t in the best shape. Some even have stains.”

.

THE UNKNOWN

After purchasing the record for 5,000 yen in Kyoto, Brent faced a new challenge. What to do with the record while sightseeing – well, because he did actually have to do some sightseeing with his family. He carried his newly acquired vinyl treasure with him on strolls through some of Kyoto’s many shrines and then the next day he made his way up the steep steps of Crow Castle in Matsumoto with a bag holding his record. He didn’t want to leave the record in the rental car for fear it might warp, so instead the vinyl became a tourist itself.

Back in Tokyo, the record stayed nestled in a hotel before meeting new vinyl friends – Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity, Anthony Braxton’s For Alto and Burton Green’s self-titled Quartet album among others – purchased in several more impressive record shops around the city. The Japanese seemed to flip through the records quicker than anyone he’d ever seen. The free jazz sections were substantial and well curated. He loved every minute there.

Zig zagging Shibuya crossing with a bag full of vinyl records looked like a challenge, but like free jazz itself there seemed to be some order to the chaos, at least some of the time. The next morning, the records would board a plane to the United States. For some, like Black Woman, it meant going home. Yet it still meant heading towards a new turf, a different needle, ending and flowing through its reams. What scratches, stains and warps were to come were unknown, but there were screams to be heard. The world would not cease it’s violence. There would be more casualties and more revolutions, but with proper care and luck, the vinyl would keep on spinning.

.

.

___

.

.

.

.

.

Listen to guitarist Sonny Sharrock play “Peanut” from his 1969 album Black Woman, with Dave Burrell (piano); Norris Jones (bass); Milford Graves (drums); and Linda Sharrock (voice).

.

.

___

.

.

Click here for details on how to enter your story in the Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

.

Click here to read “Celestial Vagabonds” by Max Talley, the winner of the 56th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

.

.

.