Brown University professor Michael Harper, the first Poet Laureate of the State of Rhode Island, and author of the National Book Award nominated collection, Dear John, Dear Coltrane, discusses John Coltrane and reads his poems.

_______________________________________

JJMI am aware of your work around Coltrane, and welcome your participation in this discussion. Coltrane’s music, and the music of free jazz, helped broaden reality and the canvas on which artists could now express themselves grew. How did Coltrane’s music open the world of poetry for you?

MH Well, first of all, his stance. After Parker, there is Coltrane, and then there is nobody else. I am a guy who grew up loving tenor music. I loved Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins and Sonny Rollins. I went to high school and college in Los Angeles, and Charles Mingus and Dexter Gordon were my role models when I was a kid. I graduated from high school when Charlie Parker died, and nobody in my class knew who Parker was with the exception of a handful of musicians. Eric Dolphy went to the same high school as I did, but he is not a contemporary of mine, he is older than me. So I didn’t know him. Don Cherry and Billy Higgins were classmates of mine – guys I went to school with. One of the reasons why I didn’t become a musician was because there were so many musicians who were better than I was. I knew I had better find another job. I certainly couldn’t compete with them. I was young enough to know that I couldn’t do those kinds of things.

JJM You wish to share your poetry with us?

MH Yes. I would like to read three poems on Coltrane, and then I am going to read Dear John, Dear Coltrane, which is where I started. When I am done reading them, you come back and ask whatever questions you wish.

The first poem is called, A Narrative in the Life and Times of John Coltrane, Played by Himself. The poem takes place in Hamlet, North Carolina, where he was born, and it talks about all the things that got him from North Carolina to New York City and all that time he spent in Philadelphia.

A Narrative in the Life and Times of John Coltrane,

Played by Himself

Michael Harper Reads the Poem

I don’t remember train whistles, or corroding trestles of ice

seeping from the hangband,

vaulting northward in shining triplets,

but the feel of the reed on my tongue

haunts me even now, my incisors

pulled so the pain wouldn’t lurk

on “Cousin Mary;”

In High Point I stared

at the bus which took us to band

practice on Memorial Day;

I could hardly make out, in the mud,

placemarks, separations of skin

sketched in plates above the rear bumper.

Mama asked, “what’s the difference

‘tween North and South Carolina,”

a capella notes on our church choir

doping me into arpeggios,

into sheets of sound labeling me

into dissonance.

I never liked the photo taken with

Bird, Miles without sunglasses,

me in profile almost out of exposure;

these were my images of movement;

when I hear the sacred songs,

auras of my mother at the stove,

I play the blues:

what good does it do to complain:

one night I was playing with Bostic,

Blocking out, coming alive only to melodies

when I could play my parts:

And then, on a train to Philly,

I sang “Naima” locking the doors

without exit no matter what song

I sang; with remonstrations on the ceiling

of that same room I practiced in

on my back when too tired to stand,

I broke loose from these crystalline habits

I thought would bring me to that sound.

_________________________

Driving the Big Chrysler Across the Country of My Birth

Michael Harper Reads the Poem

I would wait for the tunnels

to glide into overdrive,

the shanked curves glittering with

truck tires, the last four bars

of Clifford’s solo on “`Round Midnight”

somehow embossed on my memo stand.

Coming up the hill from Harrisburg,

I heard Elvin’s magical voice

on the tines of a bus going to Lexington;

McCoy my spiritual anchor–

his tonics bristling in solemn

gyrations of the left hand.

At a bus terminal waiting to be taken

to the cemetery, I thought of Lester

Young’s Chinese face on a Christmas card

mailed to my house in Queens: Prez!

I saw him cry in joy as the recordings

Bird memorized in Missouri breaks

floated on Bessie’s floodless hill:

Backwater Blues; I could never play

such sweetness again: Lady said Prez

was the closest she ever got to real

escort, him worrying who was behind

him in arcades memorizing his tunes.

Driving into this Wyoming sunset,

rehearsing my perfect foursome,

ordering our lives on off-days,

it’s reported that I’d gone out like Bird

recovering at Camarillo,

in an offstage concert in L.A.

I never hear playbacks of that chorus

of plaints, Dolphy’s love-filled echoings,

perhaps my mother’s hands

calling me to breakfast, the Heath

Brothers, in triplicate, asking me to stand

in; when Miles smacked me for being smacked

out on “Woodn’t You,” I thought how many

tunes I’d forgotten on my suspension

of the pentatonic scale; my solos

shortened, when I joined Monk he drilled

black keys into the registers of pain, joy

rekindled in McCoy’s solo of “The Promise.”

What does Detroit have to give my music

as elk-miles distance into shoal-lights,

dashes at sunrise over Oakland:

Elvin from Pontiac, McCoy from Philly,

Chambers from Detroit waltzing his bass.

I can never write a bar of this music

in this life chanting toward paradise

in this sunship from Motown.

_________________________

Peace on Earth

Michael Harper Reads the Poem

Tunes come to me at morning

prayer, after flax sunflower

seeds jammed in a coffee can;

when we went to Japan

I prayed at the shrine

for the war dead broken

at Nagasaki;

the tears on the lip of my soprano

glistened in the sun.

In interviews

I talked about my music’s

voice of praise to our oneness,

them getting caught up in techniques

of the electronic school

lifting us into assault;

in live sessions, without an audience

I see faces on the flues of the piano,

cymbals driving me into ecstasies on my knees,

the demonic angel, Elvin,

answering my prayers on African drum,

on Spiritual

and on Reverend King

we chanted his words

on the mountain, where the golden chalice

came into our darkness.

I pursued the songless sound

of embouchures on Parisian thoruoghfares,

the coins spilling across the arched

balustrade against my feet;

no high as intense possessions

given up in practice

where the scales came to my fingers

without deliverance,

the light always coming at 4 A.M.

Syeeda’s “Song Flute” charts

my playing for the ancestors;

how could I do otherwise,

passing so quickly in this galaxy

there is no time for being

to be paid in acknowledgement;

all praise to the phrase brought to me:

salaams of becoming:

A LOVE SUPREME:

____________________________________________

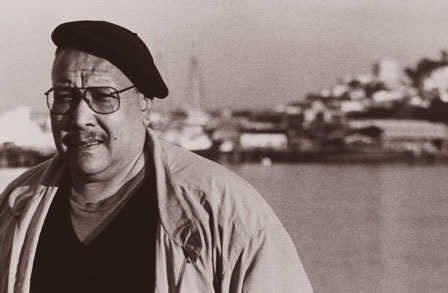

The Five Spot

by Kevin Neireiter

*

MH I wrote Dear John, Dear Coltrane in 1966, just before Trane died, and I didn’t publish it until 1970. When I first wrote it, I thought to myself, are you writing this man’s death warrant? The poem begins with Coltrane himself singing. The first three words in the poem are the fingers and toes of Sam Hose, who was lynched and dismembered. Sam Hose is a very important person. A guy named Steven Henderson once asked me if I were making an allusion to Sam Hose at the beginning of Dear John. I said, yes, I was. He said I was the only person who ever put that in its proper context, and of course there is a section here that simulates the black church and that particular section has the same answer to every question, so I just want you to know its coming.

Dear John, Dear Coltrane

Michael Harper Reads the Poem

a love supreme, a love supreme

a love supreme, a love supreme

Sex fingers toes

in the marketplace

near your father’s church

in Hamlet, North Carolina–

witness to this love

in this calm fallow

of these minds;

there is no substitute for pain:

genitals gone or going,

seed burned out,

you tuck the roots in the earth,

turn back, and move

by river through the swamps,

singing: a love supreme, a love supreme;

what does it all mean?

Loss, so great each black

woman expects your failure

in mute change, the seed gone.

You plod up into the electric city–

your song now crystal and

the blues. You pick up the horn

with some will and blow

into the freezing night:

a love supreme, a love supreme–

Dawn comes and you cook

up the thick sin ‘tween

impotence and death, fuel

the tenor sax cannibal

heart, genitals and sweat

that makes you clean–

a love supreme, a love supreme–

Why you so black?

cause I am

why you so funky?

cause I am

why you so black?

cause I am

why you sweet?

cause I am

why you so black?

cause I am

a love supreme, a love supreme:

So sick you couldn’t play Naima,

so flat we ached

for song you’d concealed

with your own blood,

your diseased liver gave

out its purity,

the inflated heart

pumps out, the tenor kiss,

tenor love:

a love supreme, a love supreme–

a love supreme, a love supreme–

____________________________________________

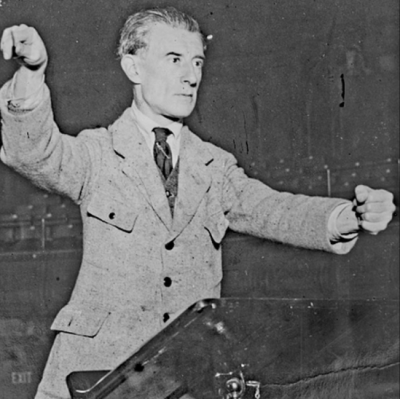

Drummer Elvin Jones

by Kevin Neireiter

JJM Tell me about these poems You were nominated for awards, weren’t you?

MH My first book was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, and it was nominated for the National Book Award, but it didn’t win. When Ralph Ellison wrote that famous essay, “What Would America Be Without Blacks?”, which was in a special issue of Time, April 6, 1970, with Jesse Jackson on the cover, there was Ralph’s centerpiece essay and there was a number of people who also had reviews – people to look for the possibilities of development, etc – and Dear John was reviewed in that same issue. I had my review in the magazine without a picture, and I didn’t expect anyone to pay attention to it from then on. Although I have won some awards, none of them were big. I am not undercompensated. First of all, when you write poetry, you aren’t writing it for money, anyway. There is no room in the marketplace, unless you are Rod McEwen or Rita Dove. I am a guy who has to teach for a living. I thought it was a bonus when somebody published my poems.

JJM In your poem “Peace on Earth,” you wrote:

In interviews

I talked about my music’s

voice of praise to our oneness,

them getting caught up in techniques

of the electronic school

lifting us into assault;

My question is, was Coltrane successful in his attempt for using music as a medium for transcending the divisions of our society, or was it considered by mainstream America as more of an assault on our culture?

MH First of all, everybody said about Coltrane’s music, even when he was playing “Chim Chim Cher-Ee,” that because there was such energy in the performance that he was angry. This is a typical way that Americans misread intensity. They hear intensity and particularly intensity in a Black American formulation which has a certain kind of repetition in it, and they translate that into anger, which is to misunderstand all the sacred conventions that black people come out of. For example, if you ever spent any time in a Pentecostal church, and you see people falling out, singing the sacred songs, nobody in their right mind would think this is about anger, this is about a whole lot of other things. It is about getting out of one’s pain. If somebody “falls out,” once you think about the affliction that they are under that they needed this kind of exorcism in order to get through their days. That is why church was so important, so fundamental.

JJM “Stomping the blues,” as Albert Murray would say…

MH Of course. When you hear intensity and you hear anger, there is something wrong with you culturally. We as Americans are basically cosmetic people. We like simple-minded things that can easily be repeated and memorized. An example is to watch kids walk around and after one or two listenings have the lyrics of a song down. When Lester Young was playing with Count Basie at the Savoy, and was watching these dancers for inspiration so he could solo and not be bored to death, what is it that the dancers were doing that inspired Lester Young, and why was he paying attention to the lyrics to these songs? The answer to that is that there was a transition between dance music and big band music of the 1930’s, and what the supposed devotees of bebop did in the 1940’s and what they were trying to do (no one really wants to talk about this), is get beyond the conventions of entertainment and the way in which entertainers were treated. That is to say as minstrels, in order to get to a point where they could perform and be themselves on their own terms, and basically to play for themselves. Anybody who wanted to listen was welcome to. This is more about the marketplace than anything else.

________________________________

Dear John, Dear Coltrane

by

Michael Harper

________________________________

John Coltrane products at Amazon.com

Michael Harper products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

Interview took place on January 24, 2002

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with John Coltrane pianist McCoy Tyner