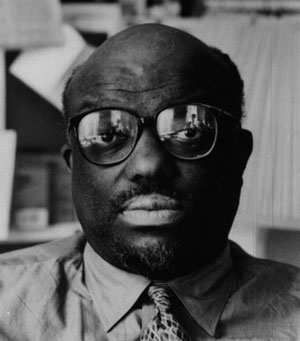

Stanley Crouch — MacArthur “genius” award recipient, co-founder of Jazz at Lincoln Center, National Book Award nominee, and perennial bull in the china shop of black intelligentsia — has been writing about jazz and jazz artists for over thirty years. His reputation for controversy is exceeded only by a universal respect for his intellect and passion. As Gary Giddins notes: “Stanley may be the only jazz writer out there with the kind of rhinoceros hide necessary to provoke and outrage and then withstand the fulminations that come back.”

Now, in a long-awaited collection, Crouch collects fifteen of his most influential, and most controversial pieces (published in Jazz Times, The New Yorker, the Village Voice, and elsewhere), and includes two new essays as well. The pieces range from the introspective “Jazz Criticism and its Effect on the Art Form” to a rollicking debate with Amiri Baraka, to vivid, intimate portraits of the legendary performers Crouch has known.

Now, in a long-awaited collection, Crouch collects fifteen of his most influential, and most controversial pieces (published in Jazz Times, The New Yorker, the Village Voice, and elsewhere), and includes two new essays as well. The pieces range from the introspective “Jazz Criticism and its Effect on the Art Form” to a rollicking debate with Amiri Baraka, to vivid, intimate portraits of the legendary performers Crouch has known.

The first, autobiographical essay reflects on his life in jazz as a drummer, a promoter, a critic, and most of all a lover of this quintessentially American art form. And the closing essay, about a young Italian saxophonist, expresses undaunted optimism for the worldwide vibrancy of jazz. Throughout, Crouch’s work reminds us not only of why he is one of the world’s most important living jazz critics, but also of why jazz itself remains, against all odds, an elemental component of our cultural identity.#

Crouch — who has appreared several times as a guest on Jerry Jazz Musician — discusses his book and other topics in a September, 2006 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita.

*

“Throughout everything that I have done in Manhattan since 1975, much of which falls outside of music, I have maintained my love for the unsurpassed variety of that inimitable sound, and have continued to evolve an ever-deeper feeling for what distinguishes it and how jazz became the uniquely great art form that it continues to be.”

– Stanley Crouch

______________________

JJM Considering Genius is a collection of your jazz writings from 1977 to the present. How did you determine which essays to include?

SC I actually had a number more, but the publisher wanted me to cut it down by about fifty thousand words, so I picked the essays I thought would work well. I initially intended to put the Sonny Rollins piece in, but it would have made the book too long.

JJM The essay that was in the New Yorker?

SC That’s right. But I hope to include that in the next collection.

JJM Are you still writing about jazz on a fairly regular basis?

SC Not in any particular publication, but I do things sometimes for Slate magazine.

JJM You wrote of Billy Higgins, “Higgins was so sympathetic to whomever he was playing with that he didn’t impose his beat upon anyone else; he remained characteristically himself but played their interpretation of the beat. This is major, not minor.” Why do you consider Billy Higgins to be the symbolic hero of your book?

SC Because he was so empathetic to other players that he could fit in with many people. He knew how to listen. Billy Higgins played with such buoyant feeling that it was a great pleasure for other musicians to have a guy on the bandstand whose fundamental goal was to play with you rather than impose his personality on you. He provided the kind of response to what you were playing that would make you better, while also satisfying him. Billy Higgins could do all of the things a musician hopes to achieve when playing, and he could do them in such a way that was so extraordinarily sympathetic that they worked with just about everybody he played with.

JJM So, he was a versatile musician

SC Yes.

JJM Is versatility something you try to accomplish with your writing?

SC Yes, if I can, but as a writer I don’t know if I am close to being able to do what Higgins can as a musician. But, let me say this — I hope to be someday.

JJM What best describes you; a writer, a critic or a philosopher?

SC A writer will do.

JJM Your writing stirs up a lot of emotion. Whenever I read your work, I tell myself that it is good he has the courage to say these things out loud because these are things that need to be said, and other times I find myself snickering at your opinions. You certainly wear your heart on your sleeve, which has to be a large part of your success

SC You never know.

JJM Your style and opinions have made you enemies, but I don’t imagine you got into this because you had fear that somebody might not like what you write.

SC I got over that quickly.

JJM Are there columns you’ve written in the past that, in retrospect, you would like to go back and change or set fire to?

SC I think every writer has written material that, in retrospect, he wishes had not been published, or maybe could have been articulated differently, but when you’re in this game as I long as I have been, and when you have been published in as many different places as I have, you just have to take it as it falls. Sometimes you get through what you want to get through, and sometimes the outcome is regrettable. But, you hope for a good batting average. That’s what I shoot for. I don’t assume that every piece will be perfect.

JJM How has your experience with jazz influenced your columns in the New York Daily News?

SC One of the things is that it has taught me how to pay attention and listen to people. What I try to do in my Daily News column is get the real feel of the city or an event or what in my interpretation seems to drive the people involved in the action, and I think that close listening to music of any kind probably helps to do that.

JJM Is communicating values in your writing important to you?

SC Yes. A writer is always communicating some set of values, even if he writes that he doesn’t have any values. A writer can’t make a statement that doesn’t in some way communicate what he believes — even if he is just reporting his vision of the world. His values will eventually come out.

JJM In the introduction to The Romantic Manifesto, Ayn Rand wrote, “Renunciation is not one of my premises. If I see that the good is possible to men, yet it vanishes, I do not take ‘Such is the trend of the world’ as a sufficient explanation. I ask questions such as: Why? — What caused it? — What or who determines the trends of the world?” Do you share this philosophy?

SC I grew up during the civil rights era, and the fundamental proposition at the time was that something wrong is going on, and it has been going on for a very long time. It was a time when there was no mercy at all — little kids were being blown up in church, and people were being shot in the streets. All of this was going on, but the will of the civil rights movement was that, regardless of the costs, we are going to do what needs to be done. So, I’ve always tried to follow my own sense of what was right, even if it caused me to come out in opposition to something that is generally accepted.

JJM You are not afraid to write about things as you see them

SC I just say what I think. It could be moral or it could be aesthetic, it could be political, it could be social — whatever it is, I just say it. I’m one of those people whom they describe as “calling them like they see them.” So, that’s it. If I think it’s good, I’ll say its good. If it’s bad, I don’t care.

JJM Are we in another era of what Rand called, at that time, “moral agnosticism?”

SC To some extent. I think a lot of people today are afraid of being called “old timers,” because when they were young, the “old timers” were the people who defended segregation, sexism, racism, McCarthyism, and a lot of negative elements that, in retrospect, were conventional forty or so years ago. Now that these people are in positions of power, many of them are absolutely terrified of being considered out-of-date or being seen as an “old-fogey” for supporting something that may be “old hat.” An example of the kind of result you get from this is that a song like “It’s Hard Out Here For a Pimp” — which essentially sympathizes with a pimp — wins the Academy Award for best song. I find it impossible to see how being a pimp is a virtue, but in this distorted time, a pimp is seen as a rugged individual, as somebody who makes it on his own by not playing by the rules and who fits conveniently into this obsession we presently have with rule-breakers.

JJM So he is revered for being an outlaw…

SC Yes, and I don’t buy that.

JJM In overcoming this kind of reverence for the outlaw, given the ease of access to information today, it would seem that people are in a better position to learn about the heroic figures of our past who can help us achieve a higher potential than a generation ago

SC I try to clarify who I think the heroic characters of the art are in Considering Genius, and in the introduction I discuss a certain kind of heroic embrace of the democratic imperative that you see in the works of Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray.

Part of what I do when writing a book like this is to seek a way to point out to readers what is in the material that makes these people heroic. Sometimes, particularly in the world of jazz, there are things about people like Miles Davis or Charlie Parker, for example, that are not particularly pleasant, but those things do not really intrude upon what made them both great musicians at the time that they were great. In other words, you can’t necessarily ignore people who do remarkable things just because there are elements in their personality that are not attractive.

JJM You have issues with Miles Davis, and how he led his life

SC Yes, he’s a perfect example, as is Charles Mingus, who I write about in the introduction. During a rehearsal I went to, he simply flipped out and fired the band, and while he acted like a lunatic for a moment, that didn’t intrude on his greatness as a musician.

JJM What is the role of the jazz critic?

SC The role of the jazz critic is the same as any other art form. A critic attempts to identify what the form is and then discusses what makes it a good or not so good performance. In my book I find myself writing about those kinds of qualities, but I also raise arguments in the collection of essays called “Battle Royal” with this kind of “how anything goes” aesthetic today. I don’t believe that. There are people today who become absolutely hysterical about the idea that jazz has any definition at all. They hate that idea. I don’t know of any other art form in which people spend the amount of time and energy they do in denying that jazz has a definition.

JJM This argument has been going on for a long time. In the forties, jazz critic Sydney Finkelstein wrote, “Experiment and change are in the essence of jazz.”

SC That’s all good, but that is not the problem. Some of my more simple-minded critics interpret me saying that there should be no experimentation, innovation or imagination, and that musicians today should just recycle old material. The thing that fascinates me about the “avant-garde” of today is that it seems to be more novelty than any kind of substantial interpretation of the fundamentals of the art. My contention is that once you recognize what the fundamentals of an art are, you can re-imagine it and understand where the deepest innovation comes from. I hear some people doing that, but I don’t hear a lot of people doing it. I think that a lot of people who write about the music today are really rock n’ roll people, and they just like the idea of what Robert Hughes calls “the shock of the new.” But sometimes the shock isn’t the news, the shock is something else.

JJM Let’s go back for a minute about the role of the jazz critic. It seems to me that the role and importance of a jazz critic is different than that of a rock n’ roll critic, for example, because jazz is so underexposed, while our culture is inundated with information about rock music. If I want information about rock n’ roll, I can get it by watching a show like Entertainment Tonight just about any night of the week, whereas if I want information about jazz, there are so few resources that I have to rely on a trusted critic, which elevates their importance.

SC As far as reaching the mass is concerned, the important critics are the ones who write for the widest distributed media. Gary Giddins or myself can write many things, but a one page article with a half page of photographs of someone in the New York Times can do far more than a long detailed essay by Giddins, by Francis Davis or by myself writing what we think about that same guy. The problem is that there is so much material out there that the public doesn’t necessarily know what to ask for, and they don’t know what to look for. People have access to so much entertainment that they are looking for someone to help them make choices.

JJM You write about a “car dealer” mentality that exists in jazz magazines. What do you mean by that?

SC In Considering Genius, I point out that a lot of these guys talk like car dealers do, who say things like, “This is our new model.” But in the world of the arts, “old” and “new” doesn’t really mean anything. Oftentimes, critics — or people who call themselves critics — are obsessed with newness and are looking for something like a new trend . It seems to me they are not really interested in the substantial weight of the idiom that the artists are working with, and this has a bad effect because it causes listeners to dismiss things that the critic has not mastered. For example, if a writer dismisses a musician by saying he has not mastered harmony, it very well could be that he is dismissing something that he’s not sophisticated enough to critique. Musicians like Joe Henderson, Wayne Shorter, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins and Thelonious Monk were sophisticated players, and what they were doing was not some random aspect stuff — although I feel that Coltrane lost his way

JJM Sure, but turn the clock back to 1946, and Monk’s music certainly turned some heads…

SC Yes, but what I am saying now is that’s the criteria. If you shock people, then that means you’re doing something good. Monk shocked people, but he was doing something good. People today can shock people by being inept at playing something, and they can be celebrated without having any kind of sophisticated authority. For instance, a guy like Anthony Braxton is a very sophisticated man, and you cannot compare him to a guy like Frank Wright as a musician. I think that’s a problem we have today, and I go into that in the book. I look at people like Al Foster, who added some innovative things to the playing of drums, and a pianist like Eric Reed — these are musicians who can play extremely well, but because they don’t go on the bandstand with a banner saying “I am now going to innovate,” they don’t necessarily get known.

JJM Like musicians, critics are trying to be on the cutting edge — their livelihood and reputation is often staked to being the first to recognize and recommend a new talent In your essay, “Jazz Criticism and Its Effect on the Art Form,” you wrote, “Like most American criticism, jazz writing is either too academic to communicate with any people other than professionals, or it is so inept in its enthusiasm or so cowardly in its willingness to submit to fashion that it has failed to gain jazz the respect among intelligent people necessary for its support as more than a popular art.” Are jazz critics too academic?

SC There is almost no academic discussion now at all. I feel like it is all about what critics like. Ok that’s fine. What I was talking about in that essay was that the public doesn’t know what a major third or what a minor third is, nor do they necessarily know what meter a song is in, and while the astonishingly academic level on which Gunther Schuller wrote is not something that would resonate with the public at large, at least he was trying to establish certain things in terms of music. When you step away from someone like Schuller, then you get the kind of criticism that is almost like rock criticism — basic descriptions of what the band played and what they said on stage — and I don’t think that is a sufficient assessment of the music, nor is it what the musicians want from the discussion.

JJM Regarding jazz musicians and critics, Dan Morgenstern wrote, “The jazz critic is at best tolerated and at worst despised by the great majority of jazz musicians.” Has that been your experience?

SC I don’t know if I’m despised by musicians. I never assume that anybody I don’t know is necessarily candid, especially if they think I can affect their career. So a lot of what a musician says may be based on whether or not they think what they say will help them, and if it will help the writer like him.

JJM In 1992, Sheldon Meyer — the leading jazz book editor of his time — called Martin Williams’ The Jazz Tradition, “the most influential book written about jazz in the last twenty years.” Would you agree with that?

SC Yes, I think I would. I wrote an essay called “Martin’s Tempo,” which is in the book, for his memorial. So many writers who attended his memorial thought of Martin as their intellectual mentor. He was very influential.

JJM How has new technology changed jazz and impacted its ability to be successful?

SC I don’t know. What I hear a lot is that the innovations of great engineers like Rudy Van Gelder, who understood how to deal with the nuances of sound, has not been followed up — really since the popularity of rock n’ roll. Many people I know don’t like the sound.

JJM While on the subject of people you know When did you first see Wynton Marsalis perform?

SC I saw him at the Bottom Line in New York City, which has since closed. As I write in the book, I had heard about him from Buster Williams, who told me about this kid from New Orleans who was going to shake everybody up when he came to New York. So when I saw him appear with Art Blakey, I said, “Oh, that must be what it is.”

JJM Did you introduce yourself to him at that time?

SC I don’t remember introducing myself to him then. I do remember introducing myself to him at a club that was on 97th and Columbus Avenue called Mikell’s. I invited him over to my house afterwards.

JJM In your essay called “Live at the Village Vanguard,” which is an account of your witnessing a performance of Marsalis’ there, you wrote, “As Woody Shaw told Maxine Gordon: ‘He’s going to go beyond all of us, not just on the horn but in the music. He’s going to take it some place else. I can hear it.’ Shaw was right,” you conclude. Where has he taken jazz musically that can be described as “someplace else?”

SC I think that something like All Rise is absolutely unprecedented. A work for jazz band and symphony orchestra of that length has never been written before. That’s one example. Now, sometimes with his playing, you hear him play all kinds of things no one else has played, and I talk about what some of those things are in that particular essay in Considering Genius. I also think that he has a lot in common with people like Charles Mingus and Duke Ellington, who were recognized as artists who could draw upon whatever came out of the idiom, and from any time period. He has done so many unique things but they’re not always obvious because he’s a disciple of the Duke Ellington of the Far East Suite, the Latin American Suite. He was really impressed by late Duke Ellington, but he’s not an imitator. The thing is that people don’t know Ellington well enough to know that there’s a remarkable difference between what Marsalis writes and what Ellington wrote, so much of the problem in assessing his music is that people don’t know what they are assessing.

JJM Ted Gioia, who has written histories on jazz and west coast jazz, wrote, “Marsalis the musician has been eclipsed by Marsalis the institution.” Is that a statement you would agree with and, if so, does that interfere with the jazz critics’ acknowledgment of his accomplishments?

SC What jazz critics think about him is in no way near as important as what he is doing. Nothing a critic has to say about John Coltrane is as important as he was. Nothing we say about Monk is as important as Monk was. Nothing we say about Charles Mingus is as great as what he accomplished. What I mean is that the event is the art — the criticism is no more than a footnote that is either good or bad, but it is not essential to the artist’s message.

JJM You also wrote about Wynton and the shape that jazz music was in during the seventies. “ things looked fairly grim for jazz because, in terms of aesthetic troops, younger musicians didn’t seem to have much interest in the true identity of the art.” Couldn’t it also be said that this was as much a measure of where the record companies were taking jazz?

SC Of course. In an essay called “The Presence is Always the Point,” I wrote that so many of these problems came about during the seventies because a large number of very great musicians had sold out. Sure, there were always commercial things throughout jazz history. In the late fifties and early sixties, for example, there was the soul movement, but with the exception of the bands of Art Blakey and Horace Silver, most of that was superficial claptrap. It wasn’t important music, and it wasn’t even intended to be important music — it was more like background music for a bar, which is okay, but it wasn’t as if any of those guys like Ramsey Lewis were trying to do what Monk or McCoy Tyner or Ahmad Jamal were trying to do. They were trying to fill a commercial spot and every now and then they made a good recording. As I point out in the book’s prologue, when I was coming up, I was so turned off by that kind of music that I became really excited when I encountered the music of people like Mingus, Monk, Coltrane, Miles Davis, the Modern Jazz Quartet, John Lewis’ work away from the Quartet, and George Russell’s work. There were so many exceptional players and composers who were trying to create substantially good music, and in their attempt to do that, would sometimes bend or ignore the conventions that had been put in place — to re-imagine the fundamentals of the art. That is what all these great musicians had in common, and it is what I think made them remarkable musicians.

JJM One of the earliest jazz records you listened to was by Lou Donaldson

SC Yes. I heard that when I was in high school.

JJM Was that a “soul jazz” recording?

SC Yes. The tune that got me was “Blues Walk,” and the other was “(I’m Afraid) The Masquerade Is Over,” which is the one most people played. I am not sure why it was popular — I mean, it sounded good, but when I think back on it, it was quite a leap from Smoky Robinson to James Brown to Donaldson’s “The Masquerade is Over,” which was delivered in a style that was inspired by Charlie Parker. But people played that song every day.

JJM How soon after you got interested in this music did you discover Charlie Parker?

SC Sometime in the early sixties.

JJM Are you still working on his biography?

SC The first volume will be out next summer.

JJM What is it about Parker that inspired you to spend so much of your own life studying his?

SC He was such a mysterious character, and his wild side outside of his music led to a substantial legend. Finding the real man has been very exciting. I have learned so much about him that has not been in any previous books about him.

JJM Do you remember the first recordings of Parker’s that you heard?

SC The first recordings I heard were in a compilation called The Essential Charlie Parker on Verve Records. Then I believe I heard Bird and Diz, but that was a little too advanced for me, because almost all of the tempos were extremely fast. I liked The Essential Charlie Parker because it included “Just Friends,” and the way they edited it, you could hear the Charlie Parker solo, then Oscar Peterson, then Ben Webster, and finally Johnny Hodges took it out. So, it was exciting. It was a down-home blues that Johnny Hodges and Ben Webster could really play, and it also had this super-refined, intricate, highly intellectual blues that did not sacrifice any blues feeling at all, which Charlie Parker played. It was something to hear all of those guys playing together.

JJM When I got into Charlie Parker, I remember being surprised at the poor quality of many of his recordings, and that discouraged me a little from digging deeper into his music. Did you have that experience also?

SC Yes, very much. You couldn’t hear the drummer, and while you could hear the sound of the cymbal, you couldn’t hear the beat — all you could hear was the sound of someone in the background crashing his cymbals. I couldn’t figure out the sound.

JJM What do you think the average American knows about Charlie Parker?

SC Very little. The average American has probably heard of Charlie Parker, but maybe they have never heard of Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington or Lester Young — we know they haven’t heard of Lester Young. That’s just how it is.

JJM Will it always be that way?

SC No. If we always thought it was going to be that way I don’t think we would have begun Jazz at Lincoln Center. That never would have happened if we thought it was hopeless. It’s a battle getting the works of these musicians heard, but I think in the long run, it’s going to be won.

JJM I do too. My sense is that the further away we get from the time in which they lived, the more important these artists will become.

SC But the other thing is that we don’t know which of today’s musicians will become standard bearers of the art. All we can do is go by our ears and the way that we respond to something, and react with the same level of responsibility that we feel for Armstrong and Ellington. I think that people like Marcus Roberts, Eric Reed, a real phenomenon like Wes Anderson, or a truly great bassist like Reginald Veal are people who will stand out over time.

JJM Yes, but for me, the difference is that Armstrong and Ellington performed at a time when their work not only had a significant impact on popular culture, but on society as well. Many of today’s musicians possess a virtuosity that could have put them on the bandstand with Armstrong or Ellington, but their music seems to have very little impact on culture or society.

SC Wynton Marsalis has, and on a higher level than anyone did. The difference between now and then is that there was a value to playing then. Today, on the other hand, the music scene is not driven by a desire to play well. I was talking with some people at the Village Vanguard recently about the number of young musicians who are concerned about the mechanical way jazz is learned, and how many of them go directly from an institution to the bandstand at the Vanguard, playing what Jimmy Heath likes to call “stickum,” which is just material that just sticks on something. They say there is no emphasis on the idea of melodic development or actual rhythmic complexities that deal with time as opposed to just playing in odd meters and stuff like that. So there are a lot of things that musicians have to get through in order to be able to play. The gene pool doesn’t change very speedily, so we know that the ability of people to play didn’t go away, it’s just that they haven’t been inspired to do the kind of things that would actually make them sound better.

There is a section in my book where I write about Charles Mingus. Through his work I encountered people like Mal Waldron, Charles McPherson, Jimmy Knepper, and Booker Ervin, and while not one of them could be considered an innovator or a pacesetter, they were all individual players whom you could recognize after you became acquainted with their style. These musicians were inspired to play as well as they could play, which is when you have a great art form. I am more concerned with musicians playing as well as they can play than I am about who the next Charlie Parker is going to be, because there is nothing we can do to determine that. We can’t have an international summit meeting and say when we come to the end of this meeting we will have figured out what it takes to produce another Louis Armstrong. That’s not going to work. I think those people just come up out of the ground — they always have.

People in the jazz world are so insufficiently sophisticated that they assume someone innovative is supposed to appear every fifteen or twenty years just because that happened a couple of times before, but it doesn’t mean anything. You can’t make a rule for an art form based on the arrival of innovation, because sometimes you have to go through periods of refinement. Every jazz fan knows that there was so much going on in the fifties, and there were so many people playing so many different ways, and it was unfortunate that Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane tended to take the music in two directions as opposed to the many directions that were available before 1960. For example, the bebop era that was being extended upon by Gerry Mulligan and Chet Baker was never developed, nor was Mingus’ music. Even the stuff that Herbie Nichols was playing wasn’t developed. There was a way in which Horace Silver was doing things, and that wasn’t developed either. When I talk about developed, I mean other musicians didn’t look at it and didn’t deal with it in ways they could be inspired by to create something else for themselves. Instead, guys either went into the direction of performing modal tunes like Coltrane’s band, or they went into playing tunes that didn’t necessarily have any predictable form or chord changes like Coleman’s band. I think those were only two of the directions the music could go at the time, but musicians felt that in order to be up-to-date, they had to go in either John Coltrane’s direction or Ornette Coleman’s direction.

JJM Another thing in their favor, of course, is that those men were seen as being outside of mainstream society, which was a key marketing strategy during the sixties

SC That’s part of it, but the unprecedented intensity of the John Coltrane Quartet had a charismatic effect on others players too. John Coltrane was playing so much saxophone and Elvis Jones was playing so much drums, and McCoy Tyner had invented a new piano style, and that whole rhythm section had a new way of playing rhythm. It was incredibly powerful to hear in person, and it just swallowed a lot of people up.

But, take Ellington’s Far East Suite as an example; he laid out an enormous array of musical possibilities, but, as I write in an essay on Ellington in Considering Genius, they went by like an invisible train in the night. People like to talk about how great Ellington was, but they don’t know his music, and I am sure most musicians don’t know his music either. Musicians know the same things that jazz fans do — “Sophisticated Lady,” “Take the A Train” — they know tunes, but they don’t necessarily know those super achievements that he created like Black, Brown and Beige, Anatomy of a Murder, or those incredible things on Ellington Uptown. I could go on and on about this because there are so many recordings of his that possess a musical breadth and depth which has never extended itself upon musicians. By no means am I saying that musicians today should be playing in the style that Duke Ellington’s band played in, or that of the people who performed his music played in. I’m just talking about addressing that degree of aesthetic success, and trying to figure out what it is that a musician can use out of that. I believe that has been Marsalis’ great achievement — he was able to recognize how great Ellington’s music was and how much could be learned from it and how much could be used for developing his own individual sound. I think Mingus was the same way.

JJM What do you consider your major life achievement to be?

SC I’ve never been asked that and I don’t think that I’ve thought about it. I believe the novel I wrote, Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome, is different and has something very unique about it, and I have written a number of books with essays that I’m proud of, and I’ve had an editorial column in the New York Daily News for over ten years that I believe has helped introduce some of the complexities of the local, national and international communities to the common man. Also, being one of the founders of Jazz at the Lincoln Center is something I’m very happy with.

JJM I can’t help but think that is a major source of pride. What are some of the challenges Jazz at Lincoln Center faces?

SC One of them is to raise enough money for an endowment. That’s a large amount of money, but I believe we may be able to find a few billionaires out there who believe in what Marsalis is doing, and who will contribute enough money for us to go on our merry way like the New York Philharmonic, Metropolitan Opera, or the New York City Ballet. Once we get to that point, we’ll be okay — and I believe we can get there in the next five years.

Good things are developing with the programs there. Marsalis told me that at the last “Essentially Ellington” high school band competition, for the first time there were players able to play well on chord changes, and in this era, for kids to completely free themselves from the sound of pop music and to learn enough harmony to play on chords is no minor achievement — it’s a very inspirational evolution of that program. I am hearing that the Thelonious Monk Institute is doing very well also.

If we can ever get past the car dealer mentality and focus on how well people are doing whatever people are doing, I think we’ll move along a lot faster. It is unfair to any player who is playing well to say that he is not a Coltrane or an Elvin Jones or whoever. So what? When Elvin Jones and Tony Williams were alive and when they truly exploded on the scene in Coltrane’s and in Miles’ band, there were many many drummers playing extremely well. As somebody once said to me, no matter how great they were, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Lester Young or Louis Armstrong could not play more than one gig at a time. So, when Coltrane was playing at the Vanguard on a given night, all of the other many clubs in New York had people playing in them too. That is what was great about New York when I first came here in the middle sixties — if you loved jazz, this is where it was being played, and it wasn’t just being played by John Coltrane. There were so many places you could go and truly hear people play. When I first came here you could hear music downtown, in the West Village, in the East Village, you could drive all the way to Harlem to see Art Blakey opposite Betty Carter, you could hear Don Byas, Chick Corea — there was stuff going on all over town. It was an amazing, wonderful thing. So, my feeling is that you always want to try to get back to that, where many people are playing jazz that sounds extremely good.

_______________________

Considering Genius: Writings on Jazz

by

Stanley Crouch

*

About Stanley Crouch

Stanley Crouch is a columnist, novelist, essayist, and television commentator. He has served since 1987 as an artistic consultant at Lincoln Center and is a co-founder of the department known as Jazz at Lincoln Center. He lives in New York City.

Stanley Crouch products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

This interview took place on September 11, 2006

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read Blues For Clement Greenberg, a roundtable on jazz criticism featuring Stanley Crouch, Martha Bayles and Loren Schoenberg.

_______________________________

# Text from publisher.