.

.

New Short Fiction Award

Three times a year, we award a writer who submits, in our opinion, the best original, previously unpublished work.

Julie Parks of Ennetbaden, Switzerland is the winner of the 46th Jerry Jazz Musician New Short Fiction Award, announced and published for the first time on November 5, 2017.

.

.

Julie Parks

.

*

.

Julie Parks lives and writes in Switzerland. Coming from a background of acting for film and theater in New York, she started writing scenes and plays back in school. She has contributed articles on business and culture to The Baltic Times, and her short stories have been published in Veto, The Quill Magazine, daCunha, Jerry Jazz Musician, New Pop Lit and also forthcoming in The Fear of Monkeys.

.

.

_____

.

.

.

Cotton Candy on Alto Sax

by

Julie Parks

.

_____

.

At first, I simply sit on the front steps of my building, letting the summer sun bake my knees while I’m planning my getaway, trying to decide which subway to take to get to Caroline’s place faster. I know nobody will miss me. Nobody will even notice. Not like the first time I ran away.

The first time I ran away – OK, maybe I didn’t exactly run away, as the only thing I did was leave my house in the morning to go down to New Utrecht Avenue to sit in a subway station. But I didn’t come back. I wasn’t going to. I sat there all day, until it got late and dark, and eventually even darker and so late that it was time for my mom to come home. And when she did and saw that I’m gone, she called the cops and they found me instantly. Picture a pink haired girl sitting on a bench in an all Hasidic neighborhood. Not a rocket science to spot my cotton candy stack of hair even in the middle of a dark subway station. So I was brought home that same night, safe and sound, and feeling like an outcast just like before.

But this time is entirely different. Not just because I have more experience in this matter, but because I’ve been practicing over the past two weeks. I’ve been leaving my house alone every morning while my dad’s snoring between his nighttime Budweisers and daytime Coors Lights, and exploring my options for a more inconspicuous exit, which is not an easy task, given my pink hair and otherwise showy appearance. OK, but don’t underestimate me. I can be rather determined.

Actually it’s quite funny how things turn out. Most things in the tenth year of my life are pink. We live in a pale pink two story brick house – OK, the house was equally pale pink before I turned ten, but still. My new jeans now have four faded pink patches on them. The friendship bracelets that my friend Marsha and I exchanged are in mixed colors of purple and baby pink. And then there’s the hair, which is the exact replica of my mom’s Russ troll doll. I don’t even remember which came first – her giving me the troll, laughing at my resemblance, or maybe it was me who secretly spied through my mom’s old things after we moved house and I discovered the tiny pink-haired creature with somewhat biggish ears and nose. Who knows? Who can remember anyway? I’ve been too busy planning my getaway, and my mom’s forever busy working, juggling three jobs seven days a week. She works early mornings in a bagel store on Kings Highway, then at eleven runs back to Borough Park – sometimes I get to see her for a quick juice if I run down to Avenue J station just as she’s getting off the Q express – to sell car insurance to yuppie drivers, and then at five she must take the same Q express down to Sheepshead Bay to do her Laundromat shift until midnight.

I finally stand up from my steps and, pick up a brisk pace, and head towards the same Avenue J Station, but not to see my mom, to not-see my mom.

Sometimes I don’t get her at all. I don’t get why we need to live here, in this Hasidic neighborhood, when it’s so far from two of her three jobs. OK, I know this thing how she told me that while her mom was Belgian, her dad was of German Jewish descent but then he’d left to go to America before my grandma, and when she and my mom finally arrived here three years later, they never found him. Or rather he didn’t want to be found, but OK. So now we have to live in the neighborhood that goes entirely shtreimel every Friday-Saturday, because one day she might walk into my grandpa somewhere on the street, or in one of the kosher delis, or even in the big corner Duane Reade. And also so that I would learn about my roots, which were still as Belgian blond the last time I checked.

I’m done pretending to be something I’m not, and I’m done living here. This time I really will leave. For good. This time is entirely different. This time I won’t be leaving alone. Because this time I have Caroline and my alto sax.

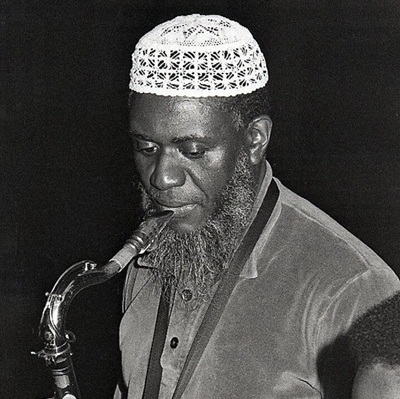

It was on one of those exploratory trips around the neighborhood that I stumbled upon what looked like a yard sale. Only there was nobody there selling nothing, and even the house looked deserted and vacant. It also looked kind of sad and left behind, like the people who’d lived there, before leaving it, had managed to pack everything but the house itself. And the house knew it would be left alone, and behind. So just outside this house, there were a bunch of metallic tools and other clutter that a ten year old girl would never know to understand or describe. But along with these deserted things was also a black vinyl case that wasn’t even empty, like I’d initially thought. OK, I didn’t know back then that it was vinyl or what vinyl even meant. That I learned only later when I first met Caroline and she told me that the golden instrument inside was a real alto sax, and she could be sure of it because nobody ever put fake instruments into real instruments’ cases.

I met Caroline in the same subway station on New Utrecht Avenue while constructing potential getaway routes in my head. It was later the same day I’d found the black vinyl case that I kept clutching tightly to my chest. The height part of my genes might be more Jewish than Belgian, as I’ve been four nine since the summer I turned seven. So that day, while standing in that somewhat empty Subway station, the case came as low as my knees, I could barely hold it up how heavy it felt, Caroline looked at me across the station – ignited by our sisterhood of blond hair, no doubt, though hers were naturally strawberry blond, and not cotton candy pink like mine – smiled and said, “My dad can probably teach you how to play that properly.”

She later told me that it had been clear as day I’d no idea what I had in my hands. She also told me I looked like a runaway because I didn’t belong in the neighborhood.

Caroline’s parents live in Sheepshead Bay, five blocks from my mom’s Laundromat shifts, of all the places. So, OK, running away to go to a place that’s actually nearby where my mom works also makes this time an entirely different experience.

I swallow hard and board a downtown bound Q express. So far I’ve never been on Subway before. Who knew these things can screech and swerve so wildly, even scarier than the Coney Island wheel. At times I fear it might actually come undone from its rails. I let my head drop against the smudgy window, a neon green graffiti elephant smiling back at me. Guess it’s not always the pink elephant in the room that nobody’s supposed to talk about. I close my eyes and let the afternoon sun settle on my eyelids, its hot touch painting my under-lids vision in yellow and purple circles. When I open them after a few minutes, we’re sliding slowly through a tunnel of black and blue streaked concrete walls that for a second make me feel imprisoned. Then we resurface just before the Sheepshead Bay station and my life is filled with summer air again.

Caroline is wearing a white and blue dress with small red flowers when she meets me outside the station. “My dad says he can’t wait to see you again. My mom’s made us some rugelach.”

OK, so I didn’t mention how I’ve already met Caroline’s parents and that they’re also Jewish. But that’s just because I didn’t want to jinx my return, which was an important part of my getaway since I’m not going back, but they don’t know it yet, and also because they’re proper Jews. Not like we’re pretending to be Jewish while my dad comes from an atheist family in New Hampshire and couldn’t care less for any religion, tradition or new employment, be it in Borough Park or elsewhere, and my mom’s simply killing herself running back and forth between three jobs paying rent for our pale pink rental in a Hasidic neighborhood, claiming that it’s all for me, that one day I will understand and then I’ll be grateful.

“Hello there,” Caroline’s dad, his name’s Josef, shakes my hand. Also, I said before that they’re real Jews because they’re not so freakish like the black-clothes folks back where we live, they shake hands and drink beer and even let Caroline take Subway and watch R rated movies whenever she wants.

“Hello, sir.”

“Please, I already told you. Call me Josef.”

“OK.” OK, so maybe I’ll try and remember that for the next time.

“Girls.” Caroline’s mom smiles at us. “Want some sweeties?” I noticed it also the first time we met for tea two days ago that her mom’s eyes curve downwards when she smiles. But it’s not in a sad way. It actually makes her look sincere and like she’s so happy she might shed a tear or two. Also her eyes remind me of my mom’s Russ troll doll.

“Yeah, go ahead. Dig in. We’ll need a lot of energy today. The boys should be here soon, too.” By boys Josef means three other men like him who play a tenor sax, a trumpet and a small piano on foldable legs (though they call it the keys). Josef himself plays alto sax, like me.

OK, so I didn’t mention that I already know how to play a little. But that’s just because I still can’t believe it myself. I’m only ten so I won’t go pretending I know what love at first sight is. But that trance, that heat wave shooting with the force of a lightning bolt down to my toes, that tingling sensation somewhere behind both of my ears that I felt the first time Josef and Guy, his English tenor sax friend, played together, releasing wild and twisty tunes that lingered in between his garage walls like expensive cigar smoke sometimes does when it makes curls and circles, when it simply sits there in your proximate atmosphere refusing to leave, eventually reluctantly fading away, but not before they’ve aromatized your entire external being. That’s how all this sax thing made me feel. Like my head had lifted off my shoulders and was swinging up by the ceiling where the last remains of those sounds had gone to live forever.

Josef must have seen it swinging up there, too. Because he stopped their session, winked at me and pointed at two buttons on my golden alto sax. “Press either of these two and blow in as hard as your heart will allow it.” He smiled knowingly and resumed his session.

At first I waited and waited, letting their duet sink in, trying hard to keep my head onto my own two shoulders. I figured I might need it to remember the two buttons he pointed at.

Then the guy on the keys joined them, I can’t remember his name, and the overall sound escalated, also picking up the speed. I waited for their fourth guy to also start playing his trumpet and it was then that it simply got too much. My right foot started flapping in this off-beat mode like it belonged more to one of them instruments than my own leg. I think I could hear my heart beating along with that trumpet’s notes. And then tenor sax. And then I inhaled and pressed on the first button Josef had pointed at and blew so hard my ears popped, so hard my eyes fell closed. And so hard even that all of that pink cotton candy hair of mine stood up and flew off my shoulders along with my head.

The second time I closed my eyes to blow in, pressing the other button Josef had pointed at, the skin on my body thinned and evaporated until I was no longer a physical mass of a human being. I was simply a moist existence filled with breath and sweat. I heard flies swooshing and flapping their near-transparent wings above the headrest of my bed, my mom sneaking in to kiss me goodnight, her hair smelling of detergent and rubber. I heard glass shattering somewhere outside. I heard sighs and broken springs in our living room couch. I heard my mom talking to nobody but herself. I heard prayers. And I blew even harder. I blew as hard as my heart would allow it before breaking into million pieces. And then I stopped to inhale and opened my eyes.

There were four pairs of eyes gazing at me suspiciously.

“Holly Moses, child. You sure got it in you.” Josef exclaimed. “You sure, this the first time you blowin that sax?” He raised his left eyebrow.

I smiled and swallowed the tears that were already welling up under my eyelids. I nodded and inhaled even deeper, gasping for air that I’d just given so generously to my alto sax.

We did two more sets like that, during which I blew and pressed buttons five more times. Josef even told me I could switch between the two buttons in the same blow, see how that sounds. But I barely heard him. My head kept swinging up by the ceiling.

That night he made me a promise to teach me an actual tune the next time I came, and I made myself a promise to never leave the next time I came.

So OK, now you see why I didn’t want to jinx it. This simple vinyl case with its golden alto sax taught me more I ever knew about love and joy, and promises and even Jews.

“Today will be a bit different,” Josef tells me while we’re munching on Caroline’s mom’s rugelach, “We have this gig coming up down the street in the Yacht Club. So we gotta practice. But you, child,” I want to say I hate it when he calls me a child, but the way Josef says it makes it sound more like that’s my name. Like Lee Child, or Julia Child. Don’t ask me how I know who they are. I didn’t want to hate anything about Josef, so I looked up a few names on my computer at home. “You can join us if,” he holds his index finger up animatedly, and then winks, “if you can learn this one tune I will teach you today. That alright?”

“Yes, sir.” I swallow my rugelach and smile back. I know how determined I can be.

“I already told you again and again, it’s Josef.”

“Mmhm.”

Now, I’m going to skip what happens today in his garage because I’m only ten, and only half Jewish, and totally confused and lost in so many more ways. I know no words to properly describe all the emotions I experience throughout this session. But I will tell you this. I not only learn Josef’s tune, I take it with me wherever I go.

OK, so I go home after that. What else can I do after he looks at me like that, so reassuringly and kindly, he winks and says, “You go home now and practice. You got it? Practice as much as you can. Got that, child?”

“My name’s Dalia.”

“Like a flower?” he draws back and grins at me suspiciously. “What kind of a name is that?”

“I’m Belgian on my mom’s side.”

He looks at me, suddenly sad and pensive. “Saxophone was invented in Belgium. Did you know that, child?” He looks down at his feet like adults do sometimes when they think nobody will see what they’re thinking, and then as if remembering something more cheerful says, “Nah, I better call you Cotton Candy with that hair of yours.” He hugs me tight, hands me a pack of something freshly baked and doughy smelling and opens the front door for me.

“See you Saturday night,” I say and turn back towards the Subway station.

Leaning against the window in Q express, I consider telling my mom about their Yacht Club gig. Maybe she could get an evening off and come see me play – although blow is more like it. I doubt my dad would notice either of us gone for the night. I look out. The city’s gone navy blue with bright eyeballs of streetlamps. I can’t remember the last time I saw my mom home during daytime hours. I know it’s not her fault. My dad’s a lazy drunk, though he claims he’s only drinking because he’s unemployed. But my mom says it’s the recession, everyone’s unemployed, don’t see nobody else drunk all the time. She says he’s not even trying. I think he’s not trying because she’s never around to see his trying. And I think she’s never around because he’s never going to try anyway. Sometimes I wish I could press on their buttons and blow as hard as my heart allows it. See what sound comes out then.

When I reach our pale pink brick house, the windows are all dark. I go around the back and slide up my bedroom window and climb in. Everything is exactly as I left it. Three long shadows decorate the nightly wallpaper behind my bed. I climb in and listen carefully, but nothing happens. Not even my dad’s usual snoring. I fall asleep and when I wake up some time later, all I hear is a quiet prayer somewhere in the far distance, or maybe it is in my own head that’s left swinging on Josef’s garage ceiling.

The next day, and the day after that, and the day after that, because three days is what I have left until Saturday night, I roll up my bedroom window and sneak out back and walk down to the Subway station. I take Q express and stand just a block away from a bagel store on Kings Highway, then travel all the way back to Borough Park to blow my heart out under the windows of a tall insurance building, and finally collect Caroline and slouch down on the curb that’s across the street from the Laundromat her family uses regularly.

And I blow as hard as my heart will allow it, but this time I also focus on my keys – turns out they’re not really called buttons despite what they might look like. Turns out all instruments have keys of some sort.

Caroline sits next to me for a few hours. She likes to drink Starbucks coffee while her parents can’t see it. Guess that’s her getaway. I think Caroline must be a little older than me; she’s also a lot taller. I wonder what Josef thinks of her not playing an instrument. But she has no interest in music. Says she will become a lawyer. My friend Marsha’s dad is a lawyer and I’ve always thought there are no Jewish women lawyers but Caroline is certain she will become one, so who am I to tell her differently. She says all women lawyers drink Venti Lattes. She knows. Says she’s seen it in Law and Order many many times.

I think she’s also told Josef something about my parents never being around in her lawyery manner, because he’s never asked me anything personal.

Then she goes back home to pretend she goes to sleep, while she’s actually learning for her bar exam – see why I think she’s much older than me – all that caffeine making her stay up all night like a proper lawyer.

I play the tune over and over again and again, my eyes closed, ears tuned inwards and outwards. Silently expecting a quiet and maybe somewhat worried, “Dalia, it’s long after your bedtime. What are you doing out here on this street?”

But it never comes.

Instead, after three days of waiting, the Saturday night comes with its Yacht Club gig that makes me feel more exhilarated and agitated than Caroline after all of her Venti Lattes. The club is located in a simple three story building with two white columns decorating its main entrance. There’s a light blue flag hanging above the door that in capital letters says SUMMER FESTIVAL OF 2012.

As soon as we enter, my knees buckle. Not only have I never seen so many people in one room – also I might add, so many non Jews – I’ve never seen so many bottles of wine and champagne spread out on a single white table cloth, so many fishes and crabs, and oysters, and shrimp cocktails. My head is spinning with all the fruit arrangements and sharp canapé sticks on silver platters, and gigantic flower pots filled with flowers so big they look like white church bells. All the women are wearing Cinderella shoes in various colors and men have funny penguin tails on their suit jackets.

“Over here,” I hear Josef’s voice disappearing between many bare skin backs and he points to a ladies restroom. He hands me something black and makes a notion for me to put it on. “It’s Caroline’s. It should fit just fine.” He winks at me excitedly. “You ready, child?”

I nod, not sure at all. I realize sadly that tonight I will be not only wearing Caroline’s old dress, I will be his Caroline on that stage at the back of the large room. I will be the daughter that Caroline’s dad never sees playing sax, and the daughter that my mother never sees doing anything, and the daughter that my own dad couldn’t be bothered to see missing right now.

I glance at the time. The electronic clock on the wall above the ladies restroom is showing nine seventeen. My mom is probably folding Josef’s socks and shorts right now. My dad is opening the fridge in our pale pink brick house to reach for a new Heineken. Caroline is scanning page six hundred thirty two, the chapter on res judicata and issue estoppels – four words that set her apart from two parents who only know how to bake kosher pastries and play saxophone. I slip into her dress and examine my reflection in the restroom mirror. Josef’s right – it’s a fine fit. Though, I look nothing like Caroline in it, I’m sure.

I will never be the daughter any dad or mom will see blow her heart out. I am just a girl with pink hair who knows one tune and is lucky enough to have gotten away for a night of Cinderella shoes and penguin suits party. My time limit is probably also sometime before midnight, or else this fantastic dream will burst and I will run into my mom on the Q express back home. Standing there, dressed in black like her good Jewish girl, holding a golden saxophone, knowing I’m one blow away from showing her just how different I am.

When I return in the crowded main room, Josef and others are setting up on the stage. I climb up and wait until he’s alone to ask him what exactly I should be doing.

“Just blow that Belgian instrument like you know you can,” he winks and seems to want to say something more, but then changes his mind and turns to his own alto sax.

Later that night, just a little after midnight, I will share a cab ride back to Borough Park where as it will turn out, I share the neighborhood with our trumpetist who’s as Jewish as Berry White (another name for me to look up on the computer) but, OK, from his intonation I’m willing to bet this White guy is a regular Caucasian male who’s not Jewish at all. I will say goodbye. I will say I’ll see them soon again. I will hear several cheers and I will see another wink from Josef. I will go around back and slide my bedroom window up. I will lie on my bed staring at those same three long shadows stretching past my entire bed and onto the carpet. I will blink away hot tears of happiness and I will hum so quiet only my own mind will know. I will fall asleep not hearing a prayer or the broken springs of our living room couch. I will have a dreamless night of deep sleep like I never knew existed, because I will know I got away. This time for good.

But right now I blow. I blow that golden instrument like I know I can. I press on the keys playing the beautiful tune I’ve not only memorized so well I can play it with my eyes closed, but also the tune that’s become my anthem of freedom. I don’t even care about my foot that’s flapping loudly along with all the beats and rhythms. I just blow my heart out and right into that golden sax that was left in that black vinyl case only for me to find. I blow loud and hard, sending godly cries across the wide room of all the crystal glasses and wine bottles. I blow like I’m the daughter whose mom and dad are watching, applauding somewhere up front in the audience, praying at times I don’t mess up my keys. I blow so long until my ears pop and all I hear are those last words before we all started playing. That long awaited release that blew right through me while my own lips were still closed, while I wasn’t even blowing into my sax, Josef’s words announcing us, “And up front here…our newest addition…Cotton Candy on Alto Sax.”

.

.

_____

.

.

.

.

.

Nice story. Really felt with the girl and the music.

Yesssss! Right on, Julie. You truly got it — I felt what it is to be Cotton Candy, her place in the world and then the new place she went to with her alto sax. Thank you.

Wow! Awesome story!! ??

Its not so often nowdays to find a well written stories that brings warm and loving feelings to your belly. You know, the ones you feel when being appretiated and loved unconditionally. This one did! Im happy Cotton Candy found her crew.