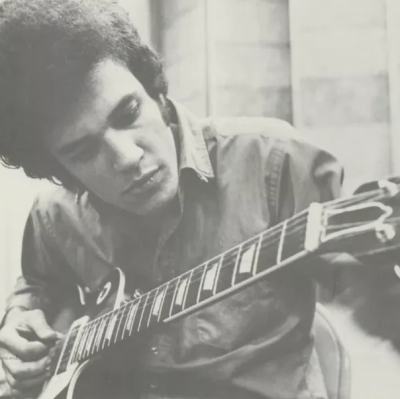

Kevin Flanagan

__________

The convergence of poetry and jazz has long been a part of the counterculture, and it has always interested me. An early interview I did for Jerry Jazz Musician was with David Amram, once known as Jack Kerouac’s musical collaborator. In the interview he talked about Kerouac’s love of music, telling me that “he had an enormous memory for music and for jazz and the classics. He could sing the melodies from different Haydn and Beethoven string quartets. He was like an encyclopedia of music and classic literature from Europe. He also had an enormous knowledge of Buddhism. He had a tremendous knowledge of Judaism, as well as the writings from the Old and New Testaments as well as from the Mass. He had this knowledge of so many different things. When he was reading, I would submerge myself into whatever it was he was reading, and I tried to anticipate what would happen next.”

So, the collaboration of words and music is fascinating, and has deep and intellectual roots. It was the basis for my interest in an email I received a while ago from reed player Kevin Flanagan who, like Kerouac, is a Lowell, Massachusetts native. Flanagan’s Riprap Quartet recordings, he informed me, “feature compositions by the band setting the works of Pulitzer Prize winning-poet Gary Snyder” and is “active in working out ways of combining music, text and improvisation.” This especially got my attention since Snyder is part of the Beat Era’s San Francisco Renaissance, and was a contemporary (and friend) of Kerouac’s and Allen Ginsberg’s. The Quartet, according to the band’s website, looks to “explore some common modes of composing and open-ended improvisation, sometimes working with spoken word in the form of readings with contemporary poets, encompassing the freedom that typified the early period of the original Beat,” and who take their inspiration “from the Beat Poets, with their freewheeling lateral association, Miles Davis and his open-ended forms, and Kerouac’s idea of the ‘Holy Goof.'”

I wrote back to Flanagan and suggested we do an interview via email about his work, which follows:

JJM Who was your musical inspiration?

KF Strangely, the first album I ever bought was the soundtrack to 2001, and I was transfixed by the all the Ligeti tracks (Lux Eterna, Requiem, and Atmospheres), which badly twisted my 14-year-old mind. After that, a year or so later there was a New Yorker-hipster/beat who somehow washed up in the Nashua, New Hampshire public library in charge of music and film who started suggesting I listen to Miles, Parker, Coltrane and Weather Report. I would spend the late afternoons doing my homework listening to LP’s with headphones on as the library silently carried on around me to a very different soundtrack. Things progressed (perhaps progressed is not the right word; maybe degenerated) on from those two places. It was both exciting and lonely, as at that time all my other friends were into the Dead, the Stones and Hendrix.

JJM Did this musical inspiration lead you to understanding a connection between spoken word and music?

KF No, that came much later; it took me a long time to get poetry, and it wasn’t until I realized that poetry only connected with me when I heard it spoken. The paralinguistic element of the text comes out in the aural realization, and adds nuanced layers of meaning that can change with each realization, like music. And like music, there’s an exchange that occurs in a live situation; something becomes a participatory process rather than an object fixed in time. It’s also that idea of whether something is interior and text-based or a public, sounding experience that unfolds anew each time. I get very inspired hearing poetry read aloud — it suddenly lives; for me it’s the difference between studying scores and actually hearing the music.

JJM Who (or what) was your link to this music/poetry connection?

KF It was probably the whole Beat thing; I read Dharma Bums when I was in my mid-teens and it was my favorite book for ages. The descriptions of the readings that were part of the whole West Coast scene were something I was a little pissed-off having missed. I also realized at this point that Kerouac came from Lowell (where my parents grew up and I was born) and his relatives were still around our old neighborhood. (Strangely, but probably not too unusual for his particular social demographic, my dad only remembered Kerouac as a local high school football hero, not as a writer). But it wasn’t the Kerouac character I was inspired by (who seemed more irritating than anything else at the time), but the character Japhy Ryder. He seemed so God-damned cool, and Kerouac couldn’t hide his sense of wonder in writing about the guy. It took me almost eight years (doah!) to realize there was an actual person behind the character.

JJM Of all the Beat era poets you could create music around, why did you choose Gary Snyder?

KF To expand on what I said above, in my late teens I wanted to be that original Zen outdoors-y Eco-warrior who was good at everything (and probably, if I’m honest, still do), who realized you couldn’t “fall off a mountain.” I have repeatedly tried to get my Japanese up to scratch, (sigh) and still get out my zafu and sit every day (well, almost every day, or at least a lot, anyway, kinda). It was the idea that spirituality had to be approached through constant discipline, not unlike the practice of music. Not the expectation of a sudden moment of satori, but the realization that this is all there is, it’s all there in front of you, and to believe that everything is going to explode into endless bliss is a sad, misguided and ultimately destructive outlook. In a way, I feel very in tune with the Roman Stoics in that sense. A good read in that sense is Van De Wetering’s AFTERzen. Mia nichi, mia nichi: bit by bit, inch by inch. Musical mastery doesn’t just arrive out of the sky in a flash of lightning; it takes years of hard, patient work. And so does anything worth doing. Where’s the point in doing the easy stuff. Your efforts should look easy, but disguise a solid base of praxis.

JJM Does Snyder’s poetry make you think of “the jazz life?”

KF Only in as so far that jazz was an “American” voice; the thing I like is the externality of his voice, giving a vision of our place in the land around us. He places all our (which is not ours as such) existence in the larger context.

JJM Who are other creators of this connection between music and spoken word (or poetry) that you feel did a worthy job of communicating the aesthetic? For example, David Amram collaborated on music with Kerouac, and the spoken word recordings of Ken Nordine stand out…

KF One of the things I noticed with a lot of attempts at accompanying readings was the dissonance of structures: it starts with Steve Allen and Kerouac reading from the TV broadcast and tended to carry on from there. Kerouac is reading free, open-ended prose, close to (if not actually – they tend to blur with Kerouac) poetic structures; Allen is playing a twelve-bar blues, which constantly cuts across the spoken word’s flow. This really doesn’t work. Allen is stuck in 4/4, in a strophic 3 x 4 bar call-and-response ( A-A-B) structure designed for something else altogether. It tends to make me cringe as I listen to it. True, Kerouac, Ginsberg et al used to goof to Dex and Wardell playing “The Chase” in ’47, trading choruses, which is of course based (very roughly) on 32-bar I-got-rhythm changes. Off their heads, and shouting extemporized lines over what now sounds fairly tame, but at that point in time it was a very wild thing that builds and builds. You have to imagine the Jazz at the Phil road show, with horn players honking, lying on their back in front of a baying crowd.

With the poets that I’ve worked with, I always try to subtly subvert their sense of metrics; I give them a pulse to play with, but try to have off-center rhythmic shapes (7/4, or bars that go 3/4-3/4-3/4-4/4, five-bar strophic shapes, et cet.) so they can’t settle into a standard 4/4, 4 bar shape, but have to show something new. I find they tend to flow more when they ignore the music and not try to force themselves into a particular shape — just work against a pulse.

JJM What about creating music to works of fiction? For example…Could you imagine writing jazz music to the novels of Kerouac, Pynchon, Roth, Updike or Salinger?

KF I did try to set a few songs with Kerouac’s prose for my CD Textile Lunch in the 90’s for the UK vocalist Chris Ingham, but had to change everything when I found I couldn’t get permission from the family to use the prose. I even sent my Auntie Francis up the street to go talk to the Sampas, but I didn’t realise that I had stumbled into the middle of an ongoing major copyright battle between the competing estates (which resulted in the slow demise of the Kerouac Center at the Lowell campus of UMass, who had wanted me to come over and do a gig before the funding dried up and the director left). Someday….

As far as the names mentioned above go, Pynchon would work, but I’ve never been a big fan of Salinger (as a local class warrior, I knew too many irritating privileged kids from Phillips Exeter, which somehow spoiled it for me), and I’m with David Foster Wallace as far as Updike goes. Nordine is a great with a fantastic voice and phrasing to die for, (he is a trained musician; I think it shows in the shapes and use of timbre) but maybe not a major poet.

Maybe the original Beat, Melville, has the perfect profile for creating music to? Eastern philosophies, he kept disappearing to sea, jumped ship in Polynesia, and bummed around New York.

JJM What is next for you?

KF Well, I just had a setting of the Diamond Sutra performed by a choir ( in my alter-ego as a composer), plus a piano trio, and I’ve been doing soundtracks for a friend’s project films. I’ve been asked to set some readings by servicemen’s wives of Wilfred Owen’s poetry as part of his WW1 centenary (which I must get on top of); plus I have a lot of material hanging fire for another quartet CD. There’s a half-finished series of songs I’m working on with the poet Malcolm Guite for an orchestral suite called the Holy Goof , which is about Neal Cassady’s last party in Mexico, with him counting the ties of the tracks between the two towns he didn’t quite get between on the Altiplano one rainy night, for tenor and chamber orchestra. And, writing arrangements for a friends sextet…and as a jobbing horn player, always available for weddings, Bar Mitzvahs….

__________

How Poetry Comes to Me

by Gary Snyder

It comes blundering over the

Boulders at night, it stays

Frightened outside the

Range of my campfire

I go to meet it at the

Edge of the light

*

A film introducing the Riprap Quartet

Music by Kevin Flanagan and Riprap Collective — poem by Malcolm Guite

Jack Kerouac on The Steve Allen Plymouth Show (1959)

Gary Snyder reads his poem “Riprap”

_____

Read my interview with David Amram, Jack Kerouac’s musical collaborator

This has been tried in the USA also and I have rejected it.

Born in USA, Jazz is American music and any ”outsider” or an American who tries to

screw it up such as the Africa .Africans , French etc is going for the jugular of the

the very basic nature of Jazz.

If you cannot play it like the Americans do (even in America there are some such

as Anthony Braxton, much later Miles Davis, Teo Macero, Archie Shepp etc who

massacred Jazz as most lovers of this music know it).

Girish

Nonsense. And of course Braxton, Miles, Shepp and Macero had the skills to have played play with Ellington or Basie, had they lived in that era. BTW Kevin Flanagan is American.