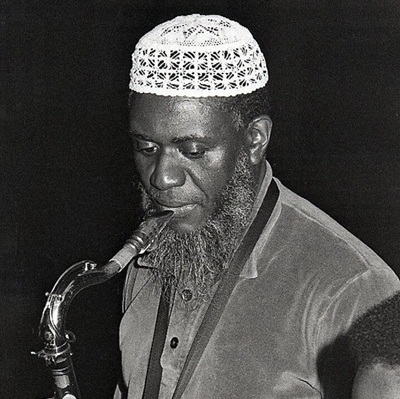

Richard Sudhalter,

author of

Stardust Melody,

The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael

______________________________________

“Hoagy Carmichael’s songs can evoke place and time as vividly as the work of Edward Hopper or Sinclair Lewis, the essays of H.L. Mencken, or the humor of Will Rogers.”

– Richard Sudhalter

______________________________________

Hoagy Carmichael remains, for millions, the enduring voice of heartland America, a beloved counterpoint to the urban sensibility of Cole Porter and George Gershwin. The author William Zinsser said of Carmichael ,”Play me a Hoagy Carmichael song and I hear the banging of a screen door and the whine of an outboard motor on a lake — sounds of summer in a small-town America that is long gone but still longed for.”

Richard Sudhalter’s Stardust Melody, the most complete Carmichael biography, is the story of his roaring-twenties Indiana youth, his days of playing alongside Goodman, the Dorseys, Crosby and close friend Beiderbecke, his peak years in Hollywood, as well as his mounting despair in the face of the rise of rock and roll.

Sudhalter, a widely respected jazz trumpet player and noted critic, broadcaster and Grammy-winning historian, discusses Hoagy Carmichael in our Jerry Jazz Musician interview.

Interview by Paul Morris.

______________________________________

JJM You write that in spite of the popularity of “Star Dust,” we are in danger of forgetting Hoagy Carmichael’s music. Could you talk about the strengths of his music that make it worth preserving?

RS In the post September 11 world, we all have questions concerning our identity. Who are we, as Americans? Why do so many people around the world hate us? What is it about America and Americans that seem to upset so many people? Because of that and because of the shock to our country, we have had to take a long look at who and what we are. The way I see it, what comes out of that is a sense that we are as our folklore represents us as being – honest, decent, hardworking, community-minded – are all qualities that are sometimes hard to see in ourselves. But if you talk to individual Americans in individual communities and ask them how they see themselves, words like honesty and decency and community keep surfacing. If you take a look at the root content of Carmichael’s popular songs, he is not a guy who wrote a lot of songs about “boy meets girl.” There is no kind of road-weary, Broadway smarts about it. He wrote about ordinary people. He wrote about going home to where the folks all know you, where you can lie under an old tree and watch the crowds go by. Though it is something that originates from early in the twentieth century, I think it has a lot of currency in our concept of our own identity today.

JJM Hoagy Carmichael grew up in Bloomington, Indiana. What did Indiana give to him?

RS Around the time that he was born and early in his boyhood, Indiana was the population center of the United States, and it was in every sense of the word the “heartland.” It was originally an agrarian culture, and it was slow in the transition from the industrial to post-industrial age. It was a collection of small towns punctuating farmland, and I think this is the way Indiana people like to look at themselves. The history of Indiana humor, for example, revolves around figures who are kind of cracker barrel philosophers or observers of the human condition. It is not without importance that, when Hoagy went to prepare for his first starring role in a move, To Have and Have Not in 1944, he fabricated a character called Hoagy Carmichael, who was drawn from his Indiana roots. This character that emerged with Cricket the piano player in To Have and Have Not was developed from movie to movie after that, and was a sort of distillation of everything he knew about his Indiana heritage.

JJM Something your book reinforces is the idea that jazz, in its early years, was not confined to the cities – certainly not to New Orleans, Chicago and New York. Could you talk about the Midwest as a birthplace of jazz?

RS Historians and critics love to put things in small boxes, stylistically, regionally, and everything else. It has been easy to talk about “Chicago-style” and “New Orleans-style” and so forth, but the development of any kind of mass-musical movement happens in a much messier way than that, and it happens all rather spontaneously. It is all well and good to talk about jazz being born in New Orleans and moving up the Mississippi and taking root in Chicago and moving to New York, but life isn’t like that. What was in the air in Chicago was also in the air in Indianapolis and San Antonio and Atlanta. Ragtime had been pretty universal. Marching band music, folk music, the blues, and all the different component parts were pretty much spread over the entire country. Black people who did so much to bring this music into existence, also lived all over the country, especially starting with the great Northern Migration of 1917, which the Chicago Defender set in motion. So, it also stands to reason that the music would be popping up all over the country. I know from experience that around Boston there were dozens of wonderful musicians who never got to make records and who are not in the history books, just because Boston was not a center of recording and broadcasting. Very often, the only way the word got around in those days was if musicians on traveling bands would come to Boston or Memphis or St. Louis or wherever and hear somebody who was just so good he couldn’t be denied. Like Art Tatum, for example, coming from Toledo. The word would come back to the big cities about it. Today, we are used to instant communication — we know what is happening all over the world in the click of a mouse — but back in the early twenties, it wasn’t like that.

JJM Another book we discussed recently was Douglas Daniels’ biography of Lester Young. He talked about Young’s extensive musical experience in Minnesota and all over the Midwest.

RS Yes. I heard about one incident in that book first hand from Eddie Barefield, a wonderful saxophone player and arranger, who told me about that winter night in Bizmark, North Dakota. He was playing Bix Beiberbecke and Frankie Trumbauer’s recording of “Singin’ the Blues” in his hotel room, and “Little Lester,” as he called him, knocked at the door and asked if he could come in and listen. Who knew at the time, certainly Barefield didn’t, what history was going to be made as a result of that very casual entry?

JJMYou write about Bix Beiberbecke that “he conferred perceptions, tastes and standards that shaped Hoagy Carmichael throughout his life.” How important was Bix Beiderbecke to him personally and musically?

RS Think for a minute about the time in Hoagy’s development when Carmichael met Beiderbecke. He was a young man and was most impressionable, at that point reaching out to the world and absorbing things as fast as he could. He had no musical training, and therefore relied on his ear. When he heard Bix play, the impression on him was as profound as, for example, the impression his college classmate Bill Moenkhaus made on him as an intellectual and somebody who was widely read and who understood things like Dada-ism and so forth. Hoagy in those years referred to himself as the “half-educated man.” He was ready for figures who would establish the templates on which the rest of his own career was going to be built on. To listen to Bix must have been quite an experience. Beiderbecke had a way of composing jazz solos that didn’t sound like anybody else. In a way, it was almost as though the minute he played the first phrase of the chorus he, in some magical, indefinable way, had the last bar in mind, though there is no sense of contrivance or planning. It is just that he thought compositionally, and that is something that we know appealed tremendously to Carmichael, and found its echo in so many of the songs he wrote later on.

JJM Was he a close friend?

RS For a time, yes. In the spring of 1924, Hoagy used his “big man on campus” status to get a lot of fraternity and sorority work for Bix and the Wolverines, who at that point were newly organized and looking around for just that kind of work. Hoagy would fix them up every weekend during the spring semester. If the Wolverines were around, it also stood to reason there was some down time, so the two of them could hang around together. I think their friendship was cemented there, and it lasted until Beiderbecke’s untimely death.

JJM You quote the tenor player Bud Freeman as saying that “he was a true jazz composer because his tunes seem to carry their own improvisation. The songs seem to improvise themselves in that they are based on true jazz phrases.” This was certainly true of his twenties compositions. How do you account for their popularity and their complexity and originality?

RS It’s a way of phrase building. You can compare it directly to a prose style. A prose style is made up of words which are formed into phrases which are formed into sentences which are formed into paragraphs which convey thoughts. Jazz improvisation is pretty much the same kind of thing. You can pick almost at random any song from any point in Hoagy’s career and realize that his methods of phrase building never really changed much. For example, if you take a song like “Two Sleepy People,” which he wrote with Frank Loesser in 1939, and put it in a Beiderbecke-like context with Adrian Rollini playing bass sax, and sing it that way, it lies under the fingers like a jazz solo. It is a jazz solo kind of figure in a way that no Gershwin, no Kerr, no Porter tune ever was.

JJMThe subjects of his lyrics in his songs were often of nostalgia, and this was a recurring theme. Was he the “king” of nostalgia?

RS We have to be a little careful when we use the word nostalgia, because it’s been trivialized to mean anything that has to do with bygone times, whether it’s high art or kitsch or camp or anything like that. Nostalgia is based on two Greek roots, meaning a pain or an ache for the idea of going home to where the heart feels at its most comfortable. It’s a yearning, a longing. I think that in dealing with the cycle of life, as many of the songs do, of birth, death, age, youth and above all what Barbara Lea very candidly calls “generic home” images of pianos, rocking chairs, rhubarb pies, he is pointing us in one direction. Yes, he is very concerned with this idea of finding yourself where life is good and where people treat you well, and you somehow feel as though the spirit is at rest.

I think this was so much a concern to him that he couldn’t resist even manipulating, toying with, interfering or improving the lyrics of his various collaborators. In fact, his work sheets are full of places where he has crossed out what the lyricist has written and injected some piece of imagery or an Indiana phrase. Seeing all of that illustrated to me beyond any question why it is that we can talk of typical Carmichael songs, even when the lyricist is Paul Francis Webster or Mitchell Parish or Stanley Adams or Harold Adamson or any of the other people he wrote with. The only lyricist whose work he didn’t alter was Johnny Mercer, who was perhaps more of a master of those images than Hoagy was.

JJM You make a good case for his uncredited role as a lyric writer in many of the famous songs. Was this discovery based on your library research?

RS Partly, but he also wrote lyrics and took credit for lyrics on more than a few of his songs, whether it be “Hong Kong Blues” or “Rockin’ Chair” or various others. In this regard, he was a very clever guy, because he realized that if he built himself as a lyricist as well as a maker of melodies – or as he liked to say a “finder of melodies” – then everybody would look to him to turn out a bang-up lyric every time out, the way they looked to Ira Gershwin or Lorenz Hart. Whereas, if he simply said that he was just a melody guy who dabbled in words now and then, he could be sure all his life of people saying that he was not even a guy who bills himself as a lyricist and he writes these wonderful lyrics, which by the way a lot of them were. That was very clever. The same thing applies to “Georgia on My Mind,” where he credits his fraternity roommate Stu Gorrell with lyric, and we know damn well that Hoagy wrote it with perhaps some ideas of Gorrell’s thrown in. It was just as well for Hoagy to give his pal a cut of the royalties for the song and take credit for the melody, because it didn’t hurt him any and he wasn’t that greedy.

JJM You write that he was a songwriter who was extremely successful in a field crowded with love songs, and he often did not write about love.

RS Yes, go through the inventory in your mind. How many love songs can you think of by Carmichael? There is “The Nearness of You,” but the number of them is very scant compared to songs about life-and-death and growing old in small towns. There are more songs like “Washboard Blues” and “Rockin’ Chair” than there are songs like “The Nearness of You.”

JJM You describe him personally as a man who in the world of Tin Pan Alley and Hollywood didn’t fit in because of his social background and attitudes. The last half of his life, partly for that reason, is sad and lonely.

RS It isn’t so much that that makes his last couple of decades so tragic and regrettable as the effects of rock and roll on the music world as he had known. I say this as an implacable foe of rock and roll in all its forms. But, imagine that in the early sixties, all of a sudden the music business changes as if overnight the people who have been making very good livings with writing and performing songs suddenly couldn’t get arrested. I mentioned in the book an interview that Hoagy did with a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation person where he questioned what was the matter with the music business? He could still write songs and was in possession of all his faculties, yet no one returned his phone calls, no one was hiring him to write songs for movies. It must have felt very strange to have everything dry up – no more film roles, no more movie assignments, no more hit songs. He won his Oscar for “Cool Cool Cool of the Evening” in 1951, but after that there is nothing even remotely resembling a hit song, although there are very good songs, “Winter Moon,” for example. By 1963 or so, there was nothing left, and it must have been a tremendous blow, and not only to him. There are many accounts of people like Johnny Mercer saying, “Hey! What happened?”

JJM I think a lot of people are familiar with his role in To Have and Have Not. Could you point our readers to other films where his performances were notable?

RS The Best Years of Our Lives, which deals with the attempts of people who had been fighting in World War II to readjust to life and home after the war. It is an extremely poignant film. There is one memorable scene in which Hoagy is playing piano in a little neighborhood bar, and a young sailor played by Harold Russell comes in, who had lost his hand in a bomb explosion. Russell had two hooks for hands he could grasp things with. Hoagy, in a deliciously sympathetic way, teaches this demoralized man to play chopsticks on the piano. It is a marvelous scene. It shows how far he had come as an actor in the years since To Have and Have Not. Another wonderful film role is opposite Kirk Douglas in Young Man With a Horn, which at some level must have its echoes of Bix, and Hoagy’s association with Bix, even at the point where he very poignantly at a railroad station asks Douglas – the Rick Martin character – if he wants to come home with him for the holidays. He refers to “home” being in Indiana. It’s interesting that Carmichael doesn’t play or sing a note in that film, but his performance is, given the passage of half a century, far more compelling than that of Kirk Douglas, which somehow seems forced and never quite convinces you that you are looking at a trumpet player. Yet, Hoagy, in everything that he says, some of which I am sure he wrote himself and shoehorned in there, is natural and he talks like a musician who has seen it all. He is perfectly at home in front of a camera. It is a wonderful performance.

JJM What CD’s that are currently available do you recommend that people check out, especially those that might be Carmichael-themed?

RS You know about the two that have come out in connection to the book, Stardust Melody and Beloved and Rare Songs. At the moment, there is not a lot else in catalog. There are a few CDs of Carmichael’s music that are played by different people. For example, the pianist Bill Charlap and his trio have a wonderful set on Blue Note called Stardust that feature guest appearances by Tony Bennett, Shirley Horn, and the saxophone player Frank Wess. There is another one on some small label by the trombonist Jiggs Whigham playing in duo with Gene Bertoncini on guitar. It is wonderful jazz performances of Carmichael standards and done in a way that underscores Bud Freeman’s pronouncement of his conviction that Hoagy is a true jazz composer. The tunes just lie there for a jazz improviser in the most inviting way.

JJM One of my favorites is the Dave McKenna album.

RS Yes, on Concord. If you can get your hands on that disc, run, don’t walk!

JJM Are there any other points about your book that you would like people to know about?

RS I would very much like to see that people of the younger generations who are, as you know in this country, are notoriously self-referential. In other words, nothing that doesn’t affect them directly is of interest, I would like to see a lot of younger people making the effort to discover who this Carmichael guy was, and why do his songs last? All it takes is listening to a beautiful performance of “Star Dust,” the one sung by Nat Cole, for example, or an instrumental performance, or of Willie Nelson singing “Star Dust” for an entirely new generation. There are some artists who continue to perform these songs, and I would like to think there is not going to be a generational phenomenon that simply fades out as people who grew up whistling and humming the tunes die off.

JJM Last question. Is the tune “Star Dust” one or two words?

RS Here is the evidence. On the one side, the one word argument, Hoagy’s own first record of it made in 1927 and all records made after that until the song was published officially in 1929, make it one word. When Mills published it, it was two words. Then, if you fast forward to 1940 on the Artie Shaw record, it is one word again. It has yo yo’d back and forth between those two usages forever. For my purposes in writing the book, I had to choose one usage and keep it stylistically consistent, but I think there is a footnote that says I am doing this arbitrarily although it has shown up as both one word and two throughout its history as a song. Take your choice!

______________________________________

Stardust Melody

The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael

by

Richard Sudhalter

______________________________________

About Richard Sudhalter

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

RS Scratch a kid from Boston and you find a once-upon-a-time Red Sox fan. My fondest dream (realized, in fact, on several occasions) was to sit in the stands along the first base line at Fenway Park and watch Ted Williams belt one (or two, or three) into the bleachers, scowl at the crowd, and disappear into the dugout. Heaven on earth. Even all the brouhaha surrounding his death, and the unseemly family squabbling over his bats, hasn’t in the least dimmed the luster of those long-ago afternoons. Splendid splinter? Dumb nickname, nonpareil ballplayer.

JJM If you could pick any event in jazz history to attend, what would it be?

RS I guess I have to split it into three even parts. To have been in the crowd at Roseland the night the Goldkette orchestra bested Henderson’s heroes. To have been in the crowd at the Club New Yorker when Rollini unveiled his wonderful new band. To have heard the Whiteman orchestra live, anywhere, in the early weeks of 1928. I’ve played many, many of those Whiteman arrangements, including lots that never got recorded until our “New PW Orch” did them in 1970s London. I well remember the first rehearsal, as the strains of “Back in Your Own Back Yard” came floating out of that large and beautifully disciplined ensemble of veteran British pros. Took my breath away.

________________________________

Hoagy Carmichael products at Amazon.com

Richard Sudhalter products at Amazon.com

_______________________________

Interview took place on July 23, 2002

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Nelson Riddle biographer Peter Levinson

*

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews