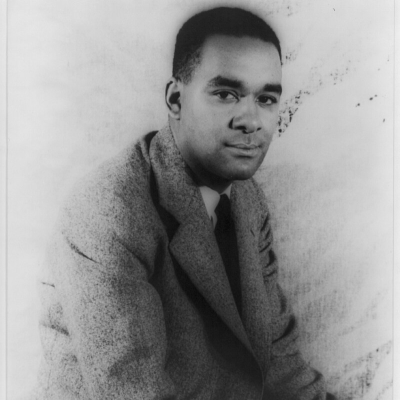

“Love makes your soul crawl out of its hiding place.”

-Zora Neale Hurston

__________

January 7 marked the 125th birthday of Zora Neale Hurston, a towering literary figure of the Harlem Renaissance whose best known published book is Their Eyes Were Watching God, a 1937 work that Time Magazine lists among the 100 best English-language novels published since 1923. Controversial at one time due to the strength of the black female protagonist’s character (resulting in the book actually being out of print for nearly thirty years), it is now considered essential reading in the study of African-American letters.

In addition to her work as a novelist, Hurston was a folklorist who studied the African-American culture of the rural South. During my 2002 interview with Carla Kaplan, author of Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, she describes Hurston as a pioneer of a group now referred to as “social constructionists,” who believed that there is no such thing as “race.” Trained in the Franz Boaz school of anthropology, Kaplan said that Hurston, among other members of the Harlem Renaissance, felt that “there was a construction essentially of a racist culture meant to tear people apart and to create false boundaries between them. At the same time,” Kaplan continues, “as an artist and as an anthropologist, she believes in race. She believes in something she called her “blackness,” her “Negroness,” and she devotes an enormous part of her own intellectual career to documenting and recording and collecting and saving it. That contradiction is not hers alone. That is a contradiction you find throughout the Harlem Renaissance and after.”

Kaplan also told me that Hurston’s goals as a writer “were really eschew of those of most of the others in the Harlem Renaissance. Everybody else was trying to create New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C. as the centers of all interesting things. She was not interested in that. She is interested in rural, southern, illiterate black culture. This is not what her peers in the Harlem Renaissance were documenting. In many ways she is on the outside of the central topics, and it made it hard for her. That is part of the reason she didn’t publish in the twenties when everyone else was because she was interested in a different milieu, and she was interested in them for different reasons. Also, her relationship with her patron during the Harlem Renaissance was extremely constricting economically and legally. She actually didn’t own any of her own productions from 1927 – 1932, which were the most important years of the Harlem Renaissance. So, much of her work was on the side and actually after the fact, which may have been useful anyway since the subject matter she took on was on the outside of that written by others of the time.”

To read my complete interview with Kaplan, which also covers the complexity of her friendship with Langston Hughes, click here.

_____