.

.

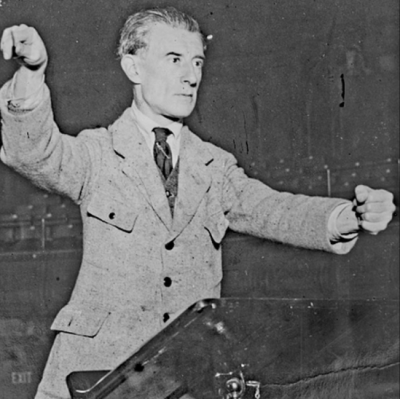

“Hound Dog Taylor,” by James Brewer

.

Queen Maebelle’s Blues

by David Rudd

.

“You wear pretty robes, but don’t have a clue

How women feel, nor colored folks too.

With your guns and whips, you dish out abuse,

Ain’t no surprise we invented the blues.”

.

…..So goes the chorus of “Queen Maebelle’s Blues,” a song on an ARC shellac disk discovered last year in a warehouse in Biloxi, Mississippi, where the contents of a general store had moldered for more than half-a-century. Almost nothing is known of the eponymous singer, Queen Maebelle Jackson, apart from the fact that she died in August 1936 from stomach cancer (as a recently discovered death certificate declares, though no birth certificate has so far been traced). Apart from that, she remains a mystery. — Richard Norton, Editorial, Blues Monthly

.

…..Maebelle had been surprised when, in 1934, a scout for the American Record Corporation invited her to come and sing at the General Store, “for our field recordings.”

…..“Field recordings?” she’d joked. “They wanna hear the Boll Weevil, close up?” She was recalling the Charley Patton song.

…..The following day, Maebelle was escorted to the store. It sold everything from household goods to pest control, from farming equipment to toys and musical instruments. After a short wait, she was led into a back room where there was a man standing over some fancy recording equipment.

…..It didn’t seem to take more than ten minutes before she’d cut her signature piece, “Queen Maebelle’s Blues,” and was back in the storefront, a five-dollar bill in her hand. The cash was welcome but, somehow, it didn’t seem enough for all the hardship packed into that song.

…..She wandered the store, clutching her windfall. Food didn’t appeal nowadays. There was little she could keep down. She opted for a few bottles instead.

.

…..It’s a great shame more is not known about Queen Maebelle. Her husky voice attests to years of hardship and trouble, and her lyrics display an unusual awareness of sexual and racial power dynamics, as demonstrated in that sardonic reference to the Klan’s dress code (their “preety robes,” as she pronounces it, as though she had a slight impediment).

…..Though it’s hard to discern through the crackle and hiss (we’re working on getting a cleaned-up version), there’s also a guitar player accompanying her. Given the insistent foot-thumping, I’d put my money on Blind Boy Quinn. This said, if it is him, his playing style is very different from classics like “Blind Boy Stomp,” now uploaded on YouTube. On “Queen Maebelle’s Blues” he’s playing open-tuned, using a steel or bottleneck. And, as others have pointed out, there’s the fact that his guitar-playing days were thought to be over by 1930, following his brush with the KKK. So, either this recording was made far earlier than others have surmised (which doesn’t tally with the ARC archive), or else Blind Boy finally overcame the debilitating injuries he received curtesy of the Klan. Once again, though, we don’t know much about his later years. A death certificate has never been found. — Richard Norton, Editorial, Blues Monthly

.

…..Roskus “Blind Boy” Quinn was born in 1897, one of a dozen or so kids of Maybel Quinn. The children’s fathers were generally absent. Roskus had many menial jobs, crow scaring, carrying water and the like, but his favorite occupation was running errands down at the Palace, where Maybel worked. He liked to listen to the music there and, recently, the regular pianist, Pinetop Curtis, had agreed to teach him a few things.

…..Roskus got there early, keen to practice his pieces before Pinetop showed up. If he could play them well enough, the man might show him some more. When sober, Pinetop was always helpful.

…..Roskus had seen various players pass through on their way to elsewhere, so it seemed to him that music might be the ticket to a more meaningful existence. He’d even written a few verses about the idea of running off to the “Promised Land.”

…..Reaching the Palace, Roskus managed to dodge Lou, the barman, for a while. The trouble was, you couldn’t practice piano discreetly. The minute his fingers started picking out a boogie, Lou was on him. In the end, Roskus agreed to work an extra hour for the privilege of being allowed to play.

…..Left alone, Roskus tried to fit a tune to his “Promised Land” words, improvising some chords Pinetop had shown him. “I’m a po’ boy, made to work the whole day through / Can’t get no rest, what’s a po’ boy to do?” It wasn’t bad, especially now that his voice was breaking, giving the words a more plaintive feel. A couple of the girls came by and stood watching him, tapping their feet. After a while, the one called Lil spoke. “You need to bend a few of those notes, Roskus,” she said, her body undulating provocatively.

…..Roskus had little idea what she meant until a traveling guitar player, Gator Harris, came by. It was he who opened Roskus’s eyes to the world of the blues. Roskus watched in awe as the older man pushed the strings of his cigar-box guitar hard against the frets, making them whine and wail. You can’t do that on a piano, thought Roskus, listening to the way Gator’s voice imitated the distressed strings.

…..Roskus was still wondering where he could get himself a box when Gator Harris up and died, expending his last breath at the Palace. Telling no one, Roskus secreted Gator’s instrument up into the Palace attic, where he went to practice whenever he could. He explored the newfound magic of flattened thirds and sevenths, which sent shivers down his spine. The “Promised Land” began to take shape, just as, he thought, did his future.

…..From then on, Roskus imbibed every bit of music that came within earshot, adapting it to suit the homemade box. With his freshly minted vocal cords, he gave the old songs a distinctive lift. He discovered that some of the women at the Palace thought so too. They didn’t just tap their feet anymore. Their hips swayed. Their eyes closed. They raised their skirts to dance.

…..Soon Roskus had just the one job, performing at any entertainment venue that would have him: bars, cathouses, juke joints, rent parties; and, between times, he played the streets. It was out on the street corners that he first adopted the sobriquet “Blind Boy,” realizing how remunerative a disability was for business.

…..Aged seventeen, he donned his dark glasses and began to roam. “I’ve got the key to the highway,” he’d sing, trying out a lyric that wouldn’t settle down till he’d travelled a good deal further. But he already had an impressive repertoire, having adapted a bunch of blues standards until they felt like his own. He never ceased to be surprised at how many of the songs he encountered involved highways and railroads.

…..Quinn was a quick learner, effortlessly assimilating the techniques of other musicians. Soon he was the one with the reputation, commanding respect around Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas. “Blind Boy Stomp” was recorded around this time. He was keen to cut it before someone else pinched his licks and claimed the tune for themselves. Quinn played it on a Martin he’d acquired in a card game, upgrading from Gator’s faithful old cigar-box.

.

…..“Blind Boy Stomp” was recorded in late 1928 (I’ve uploaded it on YouTube). The whole thing rattles along as though its performer were being chased by the devil. Blind Boy’s asides seem to make this clear —“He’s go’n’ catch ya, he’s go’n’ catch ya!” — until, that is, he adds, “wielding that fiery cross,” and you appreciate the man’s real adversary. So, when he speaks in desperation about finishing his Stomp before the hellhounds tear him apart, you realize he’s talking about runaway slaves being hunted with dogs — a practice the Klan liked to perpetuate.

…..Quinn sneaks these remarks into what is otherwise an innocent instrumental, showcasing his nifty digitry. His left hand canters up and down the fingerboard like a fugitive while his right stakes out a walking bass, held in check by the metronomic stomp of his foot. Blind Boy’s musical journey, you realize, must have started out on piano. — Anonymous Review in Blues Monthly

.

…..Blind Boy started to dress smart, too, sporting fancy suits and shoes, with a grey fedora tamped on his head. The women would flock to his dapper figure, making him a target for the menfolk. But he could handle that, especially as many thought him genuinely blind. They underestimated his speed and agility.

…..Unfortunately, it wasn’t just the husbands and boyfriends he angered. He had come to the attention of the Klan, too, thanks to some of those throwaway comments on “Blind Boy Stomp.” This “uppity negro,” they agreed, needed teaching a lesson.

…..It wasn’t long before an opportunity arose, three of them following him out of a club where he’d been playing and they’d been drinking. They kept him in sight as he ambled down the sidewalk, guitar over his shoulder. Keeping well back, the three curb-crawled along in their limo, holding back until Quinn started to cross an intersection. Then they accelerated.

…..Fortunately for “Blind Boy,” they didn’t know he was sighted. He surprised them by dodging sideways. However, he didn’t escape completely. A car door swung wide, smacking him into a ditch, smashing up his shoulder and precious Martin. It was only when he reached out for his guitar that he noticed how dark the ditch had become. Blind Boy had finally grown into that name of his.

…..Though it took Quinn several months to recover, he knew immediately that his guitar-playing days were over. His left hand just didn’t work the way it used to. Many people would have given up completely, but not Blind Boy. Music still coursed through him, craving an outlet. He switched to harmonica.

…..At first, he played it like a guitar, indulging in flashy runs, his hands fluttering as he swooped up and down the holes. It was a style that Sonny Terry would later perfect, though Quinn, with his low, gravelly voice, never tried whooping. But then something else happened that made him alter his technique.

…..A favorite with black audiences was his song “Blind Bartimaeus and me,” which drew on Quinn’s experience at the crossroads: “I woke up in daylight, but it was still night for me / Them Klan boys done took my eyes from me.” It was a catchy number, but not one anyone else would dare play. Many thought Quinn should have learned his lesson and kept quiet, but he didn’t understand that mentality, as the next lines of the song demonstrate. He jokes about the Klan stealing his eyeballs, which he thinks strange, “For they was the whitest part o’ me!”

…..One evening, a white man in the audience was so incensed he stood up and threatened Quinn. “I’ll scour out that dirty nigger mouth of yours,” he vowed. Quinn tried to ignore the man but, when his back was turned, the man twisted a broken bottle into Quinn’s face. The bluesman found himself back in hospital, lips shredded, minus a few teeth and half a tongue. They managed to stitch him back together, but his speech was never the same again; nor his harmonica playing.

…..No longer could he perform those exuberant runs. It was too painful. So, he slowed himself down, making every breath count, lingering on individual notes, exploring all they had to offer. Meanwhile, beneath the quivering reeds, first his right foot, then his left, would keep an insistent beat, his body swaying rhythmically.

.

…..We are fortunate that the pioneering ethnomusicologist, Connor Berkowitz, captured Blind Boy Quinn playing and singing in Jackson, Mississippi. Though initially renowned as a guitarist (cf. “Blind Boy Stomp”), Quinn was also a highly competent harmonicist, despite playing what was obviously an old instrument, the tuning of which leaves much to be desired. With each suck and attendant blow, he makes us painfully aware of the nitty-gritty of life: of lungs filling and emptying, of the fact that, like the hairs on our head, our breaths are also numbered. Quinn’s battle-scarred and bluesy voice, too, underscores this sense of our collective mortality.

…..Finally, as if that weren’t enough, there’s the relentless beat of Blind Boy’s boot, marking time like the Grim Reaper himself. It is particularly effective on “Key to the Highway” — a song later claimed by Big Bill Broonzy — where you can sense Quinn trudging down some lonesome road. Soulful it most certainly is, if not “sole-ful,” as the sound rises from those well-worn boots of his. — Notes from Library of Congress Field Recordings, 1940s

.

…..To Quinn, it felt as though he’d come full circle since his early days as a lackey, fetching and carrying. He’d been a guitar virtuoso with his own personalized repertoire of songs; he’d played to packed audiences and even made a few recordings; he’d dressed in style, eaten well, and had women hanging off his arms. And now, here he was, back on street corners with a beat-up harmonica, trying to earn enough for his next meal.

…..For a dime, he’d do almost anything: dance like an Uncle Tom, shine shoes, wash cars, you name it. He also knew he was not alone. Thanks to the Depression, all the old bluesmen were in the same boat — Mississippi John Hurt, Furry Lewis, Blind Willie Johnson and the rest. It was so bad, even the white people had the blues. Quinn often used that phrase, thinking he might turn it into a song one day.

…..Music was the one thing that kept him going, and it was about to take him in a new direction. Back at the flophouse, he’d acquired a battered old guitar, one that had belonged to a former resident who used to play on the streets, a little tin cup pegged to his lapel for coins. When the man finally succumbed to wood alcohol, Quinn appropriated his instrument (reminding him of how he’d acquired his first guitar from Gator Harris). No one asked questions.

…..He let it hang on the wall a while, occasionally brushing the strings as he walked by. Being open tuned, it gave out a satisfying ring, but Quinn knew that his left hand could no longer shape those notes. However, at some point, after slicing tobacco, he’d run his knife-blade over the fretboard, producing, with hardly any effort, a haunting, ethereal sound. He was immediately hooked and spent the next few weeks adapting some of his old material.

…..It sounded good and fresh — not only to him but others, too. Passing ’round their bottles of lethal moonshine, they’d sit and listen to him sing and play. Quinn was surprised at how much more resonance the old blues now seemed to possess, partly as a result of his own experiences and partly thanks to the Depression.

…..He finally risked taking the guitar out on the street. He still had his harp in his pocket, but it was painful to play, especially as he’d recently neglected it.

…..Quinn hadn’t really thought about it before, but his favorite street pitch was at another crossroads. It made sense, for it was where the people walked. So, for several weeks, Quinn played there, almost content for the first time in years. It was good to be playing guitar again, reviving his old repertoire. In fact, it worried him that his upbeat mood might be diluting some of his heartfelt blues. Perhaps, he thought, he should throw in some of those old hokum numbers, “Selling the Jelly” and the like. But his soul wasn’t in it. It was those blue notes that consumed him, and, at that particular time, they seemed to resonate with most other people in the States.

…..He knew that most of his audience were no better off than him, dressed in their rags, hugging bundles, barefoot kids trailing after them. They were all in it together. But somehow, as he shared his experiences with them, they managed a few scraps of change for him. He was always humble and appreciative.

…..One day, though, he made a big mistake. On an impulse, he thought he might resurrect “Blind Bartimaeus and Me,” which he’d not played in years, perhaps for obvious reasons. Maybe, he figured, it would now be safe, for the Klan had also gone quiet. In their own twisted way, they too were suffering.

…..As he began the song, which he’d not rehearsed, he was gratified to find the words still there, just waiting for an airing. It was therapeutic. The audience also seemed to find it so. For the most part they laughed and tapped along, but there was a small group of white men who looked anything but amused. Incensed, rather.

…..As a blind man, Quinn was initially unaware of them; until, that is, he’d delivered the infamous verse about the white eyeballs, at which point they conspicuously pushed their way to the front. The rest of the audience began to wander off, suddenly remembering errands that needed attending to, people to visit.

…..By the time Quinn finished the song, he found himself alone with his unsolicited escort. The three gave a desultory handclap before bundling him up a nearby alley where they casually relieved him of his playing knife. Then, after stripping him, they used the blunted blade to relieve him of his manhood. As one joked, “The eyeballs, nigger boy, you can keep! But these ones has to go!”

…..In a pool of his own blood, they left Quinn for dead. Fortunately, someone called an ambulance and he was taken to a black hospital where, despite a lack of resources, including anesthetic, they managed to stitch him — or some of him, at least — back together.

.

…..Apart from “Queen Maebelle’s Blues,” it seems that Queen Maebelle Jackson, as the label has it, never recorded anything else. In fact, as some have surmised, ‘Jackson’ was most likely not her name at all, simply the place in Mississippi where she lived.

.

…..When the scout had returned to the store later that day, he’d listened to “Queen Maebelle’s Blues” and been impressed.

…..“We should have got her to sing more,” he’d told the engineer. “And who’s the guitarist accompanying her? Shame he ain’t louder.”

…..“There weren’t no guitarist,” said the engineer. “She accompanied herself. Borrowed a guitar from the store — and a kitchen knife.”

.

…..It’s such a shame we don’t have more from her. But at least she’s finally got some recognition. There’ve already been a few covers of “Queen Maebelle Blues,” which seems to strike a chord with the “Me Too” and “Black Lives Matter” movements. Were she still around, she’d be astonished to see how resonant her work has become. — Richard Norton, Editorial, Blues Monthly.

.

.

A shorter, less developed version of this story first appeared in Creativity Webzine, May 2021

.

.

___

.

.

Dr. David Rudd, 70+, is an emeritus professor of literature who turned out academic prose for some 40 years but always had a yearning to give his imagination freer rein. His stories have appeared in Horla, Tiger Shark, Erotic Review, Black Cat Mystery Magazine, Bandit Fiction, Literally Stories, The Creative Webzine and a Didcot Writers anthology, First Contact.

.

.

___

.

.

The artist James Brewer works in oils on both canvas and paper, and employs abstract as well as representational approaches. Influences include the art of Willem deKooning and Henri Matisse. He lives in Nelson County, Virginia.

To view more of his art, visit his website by clicking here

.

.

Listen to the 1941 recording of Big Bill Broonzy performing “Key to the Highway”

.

.

___

.

.

Click here to learn how to submit your work

.

Click here to read “Constant At The 3 Deueces” by Jon Zelazny, the winning story in the 57th Jerry Jazz Musician Short Fiction Contest

.

.

.