.

.

Drawn from interviews with prominent producers, engineers, and record label executives, Michael Jarrett’s Pressed For All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums is filled with interesting stories behind some of jazz music’s most historic, influential, and popular recordings. In cooperation with Jarrett and University of North Carolina Press, Jerry Jazz Musician will occasionally publish a noteworthy excerpt from the book.

.

In this edition, Contemporary Records re-issue producer John Koenig, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and photographer William Claxton recall their roles in Rollins’ 1957 classic Contemporary album, Way Out West

.

.

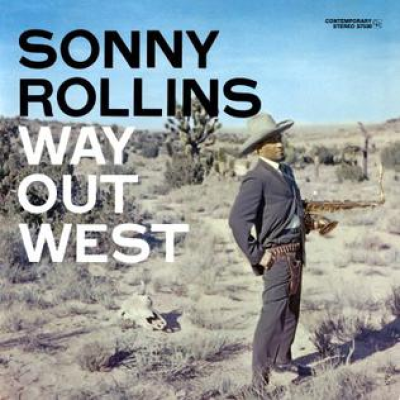

William Claxton’s photograph of Sonny Rollins’ 1957 Contemporary Records album Way Out West

.

___

.

.

Following the passing of his father Lester, who founded the label, John Koenig was president of Contemporary Records for nearly a decade. He collaborated with other labels as a producer and record executive, and over the years worked with many artists, including Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, McCoy Tyner, Wynton Marsalis, Chick Corea, and Herbie Hancock. He was the reissue producer for Way Out West.

Sonny Rollins is recognized as one of the most important and influential jazz musicians in history.

William Claxton was a photographer best known for his photography of jazz musicians, especially Chet Baker.

.

In a conversation with author Michael Jarrett, Koenig, Rollins and Claxton recall their roles in Rollins’ 1957 Contemporary Records album Way Out West.

.

.

.

___

.

.

John Koenig (Contemporary Reissues)

After the company went over to Fantasy [in 1984], they issued the catalog in not very good editions because, number one, my father didn’t add reverb at the recording stage. That was always done in mastering. He had an EMT [reverb] plate, a mono plate. Number two, [engineer] Roy [DuNann] had devised a nose-reduction system, which was very simple. He referenced the tape machine so that it would record 6dB hot at 10 kHz, and then when you played it back you referenced the machine down 6 dB at 10. That brought down the tape hiss. It was an early broad-brush Dolby system, but less complicated. If you hear a record made off a good set of lacquers, either that my father, Roy, Bernie [Grundman], or I cut at Contemporary, they are pretty spectacular sounding.

…..I tried to explain all of this to the engineering people at Fantasy when the catalog went over. Contemporary had beautiful, pristine, brilliantly mastered metal parts on the part of the catalog that was active at the time of sale, and they trashed all of them and started over again. That was a big mistake, but they weren’t going to listen to me. One of my problems in life is that I’ve always been viewed as Les Koenig’s son. I explained to them how our mastering notes worked. Every time we cut a lacquer, we wrote a new note, a new page that said what we’d done and if we’d changed anything from the prior version. These were detailed moves that you had to do because these were live [meaning not multitracked] sessions. Things had to be helped or brought down: some for purely audio reasons; some to get the material onto the disc.

…..I thought Ralph Kaffel was a very good steward of the Contemporary catalog, but I said to him, “This mastering is problematic.”

…..“Talk to George Horn,” he said.

…..I told George Horn this is what you should be doing and why. I said, “Refer to the mastering notes.” For example, Sonny Rollins’s Way Out West, with one or other of its sides, we probably did ten or twelve separate lacquers over time because the plant would blow the parts, and they would need a new lacquer. Each time we did one, we started new. [Lathe] cutter technology had improved over the years, so the high end was freer on the later versions – something unbeknown to collectors, who always want the original issue. I suppose I understand that on one level, but they didn’t sound as good as the later ones.

…..George said to me, “We want to honor what the producer said.”

…..I said, “With whom do you think you’re speaking?” It was like talking to a wall.”

MJ In addition to the sound of Contemporary recordings, your father seemed to care a great deal about how albums looked.

…..Yes, he superintended it closely. But when he encountered [photographer] Bill Claxton, for example, he’d rely on Bill’s eye. At the same time he formed a close association with Bob Guidi and, later, with George Kershaw at Tri-Arts, an arthouse company. They did layout work.

…..It was a difficult thing for me when my father died. I had been playing [cello] in the Swedish Radio Symphony in Stockholm. He died suddenly at age fifty-nine, which is younger than I am now. Rightly or wrongly, I felt that, if we were going to stay Contemporary, we needed to be a little bit more with the times. If I was recording someone who hadn’t had a record before – for example, George Cables – no one knew him as a leader. I felt like the audience needed to identify with the person. I always wanted to have a good portrait of someone who was new, so that the public could identify with the artist. While that was often the practice with the fifties and sixties Contemporaries, a lot of them were fanciful. A lot had cartoons and illustrations. As a kid, I didn’t know West Coast from New York jazz. It was all music to me. It all came to me on records, and I listened to it in my house. I wasn’t aware of the cultural significance of the Contemporary covers, particularly those from the fifties. But I think it was something my father was conscious of and did on purpose.

…..He was very detail-oriented. Whether it was Nat Hentoff, Leonard Feather, or any of the other illustrious people who wrote liner notes for Contemporary albums, they were always scrupulously edited.

MJ Most likely it comes from the Hollywood model, but, very early, he “ran credits” on albums.

…..I think you’re right. He provided all of the details about the songs; composers and publishers and so on. Also technical data, which I think Nesuhi [Ertegun] saw and emulated on Atlantic’s jazz records. Although Atlantic records looked good, Tommy Dowd didn’t make as good a studio as we had with Roy DuNann. Also, Bernie Grundman – he’s a preeminent disc-mastering guy (we used to say mastering) – he got his start at Contemporary. My father trained him to cut lacquers on the same lathe he trained me. It’s interesting. That lathe was the very lathe used to record the sound for what’s generally regarded as the first talkie, The Jazz Singer. Audio quality was one of the most important things to my father. Contemporary was known for it.

.

Sonny Rollins (Saxophone)

The one [the cover] on Way out West – it happened a long time ago. I’m pretty sure that it was my idea; the hat and the gun belt and all that stuff.

…..It was very striking, very unusual. It was a big kick at the time. But I thought it went well with playing unusual songs for a jazz album. I thought that the whole thing was really right.

…..MJ It’s incredibly funny, ironic. It anticipates one of the best jokes in Blazing Saddles. I look at it, laugh, and then think, “This isn’t funny. It’s true. There were plenty of black cowboys.” Plus jazz is metaphorically associated with myths of the West; the musician as outlaw hero; the music as a movement or push outward. The cover says that. It works on many, many different levels.

…..That’s right. I’ve never thought of it in those words, but that’s quite true. When I was a boy, I had seen these all-black films. There was a fellow who used to sing with Duke Ellington’s band, Herb Jeffries. He was in an all-black western. I remember that. I’ve forgotten whether it was Rhythm on the Range or Bronze Buckaroo, but that made an impression on me. And of course, as we all know, there were black cowboys. All of these things were on my mind.

.

William Claxton (Photographer)

I told him [Rollins] to keep his Brooks Brothers suit and skinny black tie. I knew the desert pretty well, so I knew exactly where to get the right kind of Joshua trees and cactus in the background. I went to a prop house and rented a steer’s head – a skeleton – because I couldn’t depend on finding one out there. And we put a holster on him.

…..I picked him up. He was a terrific guy to be with, very nice, and we just drover out to the high desert, near Mojave. I had shot pictures there before. I put the skull out in the sand, and he put one foot up on it. He had this long, thin body. He looked great. He just posed beautifully. And he had great fun doing it. He laughed a lot.

.

___

.

.

Listen to Sonny Rollins play “I’m an Old Cowhand” from Way Out West, with Ray Brown on bass and Shelly Manne on drums

.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

From Pressed for All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums from Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday to Miles Davis and Diana Krall. Copyright © 2016 by Michael Jarrett. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

.

.

___

.

.

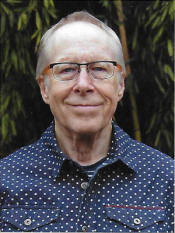

photo by Pamela Jarrett

Most of Michael Jarrett’s writing on jazz production appeared in Pulse!, Tower Records’ magazine. His day job, however, was professor of English at Penn State University (York Campus). In addition to .Pressed for All Time, his book about jazz record production, Jarrett wrote. Drifting on a Read: Jazz as a Model for Writing; .Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC; and .Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. He is now retired. He and his wife live in the village of Ojochal, on the southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

.

.

.

One comments on ““Pressed for All Time,” Vol. 9 — John Koenig, Sonny Rollins, and William Claxton talk about Rollins’ 1957 album Way Out West”