.

.

.

.

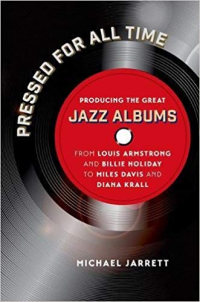

Drawn from interviews with prominent producers, engineers, and record label executives, Michael Jarrett’s Pressed For All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums is filled with interesting stories behind some of jazz music’s most historic, influential, and popular recordings. In cooperation with Jarrett and University of North Carolina Press, Jerry Jazz Musician will occasionally publish a noteworthy excerpt from the book. .

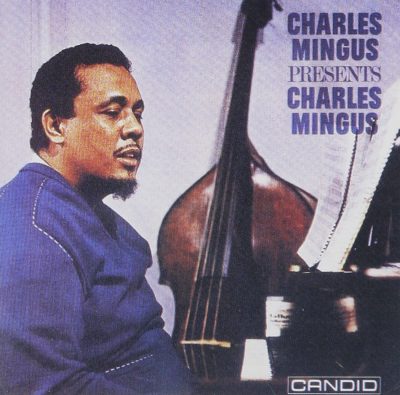

In this edition, Jarrett interviews producer Nat Hentoff about the experience of working with Charles Mingus at the time of Mingus’ 1961 album Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus— recorded for Hentoff’s short-lived label Candid Records

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

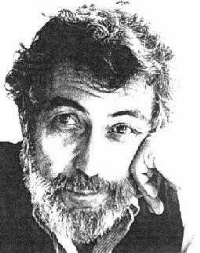

Nat Hentoff

1925 – 2017

.

…..Nat Hentoff, a prolific author and journalist whose work was published for many years in, among other publications, the Village Voice, the New Yorker, the Atlantic Monthly, the Wall Street Journal, and Jazz Times, has been described by one of his publishers, DaCapo Press, as “a man of passion and insight, of streetwise wit and polished eloquence — a true American original.” This “passion of insight” is particularly apparent in his lifelong devotion to the chronicling of jazz music — a pursuit that began even before he became editor of Downbeat in 1953 — and in his steadfast defense of the Constitution.

…..His success is evidenced by the awards he received, including the National Press Foundation Award for Distinguished Contributions to Journalism, the American Bar Association Certificate of Merit for Coverage of the Criminal Justice System, as well as the Thomas Szasz Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Cause of Civil Liberties. In January, 2004, he became the first jazz writer ever named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts.

…..In addition to his work as a journalist, Hentoff for a time was an entrepreneur in jazz, founding Candid Records in 1960 in New York, along with partner Archie Bleyer, who owned Cadence Records. While at Candid, Hentoff served as the Director of Artists and Repertory (A & R), and their albums included recordings by Booker Little, Charles Mingus, Cecil Taylor, and Abbey Lincoln.

.

.

_____

.

.

…..Norman Granz was my model. He had utter trust in the people he wanted to record. He never told them what to do, at least as far as I can remember. Even to the point where, if Charlie Parker wanted strings – and people did want them in those days; Billie Holiday wanted them – Granz against his own better judgment would do it. Some of the musicians used to complain that he’d be sitting in the control booth reading a newspaper during the sessions. But that’s when I think the session wasn’t, from his point of view, so hot.

…..Once I decided that I wanted a particular leader, then the leader decided what sidemen he or she wanted. When possible – and I think it was always possible in our cases – the leader would choose someone to edit the final tape so that the final cut was the musician’s, not mine.

…..In a sense I was a supervisor/producer or whatever. I don’t like the kind of A & R people I used to see who would, over the PA system, say something hurtful or just nasty, thereby putting everybody down. If I had anything to say to anybody, I would come into the studio and say it to the leader. I would never interfere with the sidemen because that’s the leader’s job.

…..My main job was not much of a job at all, just to keep the atmosphere congenial when things got stuck. If there was too much paper on the date, I would do what I think is the standard thing to do. I would say, “Why don’t you play the blues for a while?” That usually would manage to calm everything down, and often we would use the blues cut because it was so relaxed after all that tension. But by and large I did not interfere much at all. I made sure there were plenty of sandwiches and beer and stuff like that, which I think is an important function for the A & R man. The main thing was knowing whom I wanted. I wouldn’t dare tell Mingus or Max Roach or Booker Little or any of the people I asked to make recordings, I wouldn’t tell them what to do. I would just try to smooth things out if there were any hassles, and there were very few.

…..Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus is a famous case of smoothing things out. Did you suggest that the band dim the studio lights and pretend they were playing a club?

…..Mingus did. This is a group – [Mingus, Ted Curson (trumpet), Eric Dolphy (alto sax and bass clarinet), and Dannie Richmond (drums)] – that had been working for a long time. They were about ready to disband, and Mingus wanted an aura or an atmosphere very much like the club. I think it was the Showboat that they had been working in. It was a fairly small club, and when we came into the studio, he said to the engineer or whoever was around, it wasn’t quite darkness, but it was pretty close to it. I don’t know why, he just thought it was a good idea, and it certainly worked out very well.

…..It also helps, at least it helped me, to have an engineer who knew something about music but, more to the point, would not become the dominant force in the proceedings, like Rudy Van Gelder used to do. I mean Van Gelder is very good, but he really was a tyrant. I used a guy named Bob d’Orleans who was very hip but laid back. Again, the whole thing is atmosphere. There oughtn’t to be anything to get anybody’s back up. The only thing should be the music, and if you have either an A & R man or an engineer who wants to run the damn thing, then you’ve got a mess.

…..Years ago, [New Yorker writer] Whitney Balliett used to say, “It’s not a good idea,” and drama critics have said this, too, “to know the musicians because then it gets all involved with the reviews and stuff.” He finally decided, especially in jazz, you really have to know the musicians.

…..Mingus had been a friend of mine since I was in Boston doing radio. You just talk to musicians as people. I never had any personality problems with any musician, actually. For one thing, I guess it was clear to them (a) obviously, I’d asked them to record, and that meant (b) that I liked what they did and, more to the point, that I knew something, not as a musician but as a fan or a listener. I knew something about whay they did and why they were distinctive. The same with writers or painters or anybody else. If people have some idea of what you’re all about, then you are not likely to have any kind of temperamental problems with them.

.

.

.

_____

.

.

From Pressed for All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums from Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday to Miles Davis and Diana Krall. Copyright © 2016 by Michael Jarrett. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the author and publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Pamela Jarrett

Most of Michael Jarrett’s writing on jazz production appeared in Pulse!, Tower Records’ magazine. His day job, however, was professor of English at Penn State University (York Campus). In addition to .Pressed for All Time, his book about jazz record production, Jarrett wrote. Drifting on a Read: Jazz as a Model for Writing; .Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC; and .Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. He is now retired. He and his wife live in the village of Ojochal, on the southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

.

.