.

.

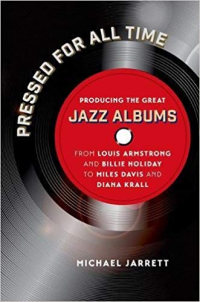

Drawn from interviews with prominent producers, engineers, and record label executives, Michael Jarrett’s Pressed For All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums is filled with interesting stories behind some of jazz music’s most historic, influential, and popular recordings. In cooperation with Jarrett and University of North Carolina Press, Jerry Jazz Musician will occasionally publish a noteworthy excerpt from the book. .

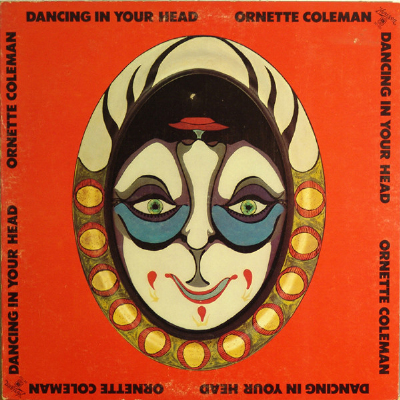

In this edition, Jarrett interviews producer John Snyder about the experience of working with Ornette Coleman at the time of his 1977 album Dancing in Your Head for Horizon Records — a division of A & M Records (under Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss)

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

.

Since 1977, John Snyder has produced over 300 original recordings, 34 of which have been nominated for Grammy Awards. He has produced albums for A & M, Atlantic, Fantasy, MusicMasters, Concord, RCA, Sony, Antilles, Verve, Private Music, Telarc, GRP, Elektra, Rounder, Columbia, Evidence, and Justin Time.

He once worked as the assistant to president Creed Taylor of CTI Records, overseeing all legal and business affairs, publishing, manufacturing, distribution, and A&R operations.

At the time of Ornette Coleman’s 1977 recording Dancing in Your Head, Snyder worked as director of the Horizon Jazz Series for A&M Records under Herb Alpert. In that same year, he founded Artists House Records, and recorded albums by Coleman, Charlie Haden, Jim Hall, Chet Baker, Art Pepper, Paul Desmond and others.

.

.

_____

.

.

…..Ornette changed my life. I spent a lot of time with Ornette. I lost my job at A&M because of Ornette. I started my record company [Artists House] because of Ornette, and I lost my record company – not because of Ornette, for sure – but because we were all working on Ornette. It was Ornette. Ornette. I had twelve people working for me at one time, and we all had some segment of Ornette’s life on our desks. It was a big job.

…..Ornette was the only musician I ever worked with who made me play trumpet with him. He made me organize a band, which he would give music to and rehearse. He called us the White House Band because we were all white. “If I can teach you guys how to play this music,” he said. “I can teach anybody how to play it.”

…..“Well, thanks Ornette. We’re glad to be of some service.” But it was cool. He’d put us in a circle and hand out music. Then he’d tell us to play. It was pretty chaotic, but it certainly was fun. He’d stop us, once in a while, tell us what we were doing wrong, or he’d tell each individual. He said things to me that made great sense.

…..The first time I played with Ornette, I was down there talking about some problems. I spent a lot of time at his loft on Prince Street, trying to keep him from getting evicted. I was ultimately unsuccessful, but I came in at a very late stage. I was able to get him some money out of it, but he had to leave.

…..I was down there talking, it was late, and he handed me his trumpet. He said, “Play this line that I wrote for [Don] Cherry.

…..“Ornette,” I said. “I haven’t played for five years. I can’t play this.”

…..“Play it.

…..I played it, got through it. It was not a big deal. “Now,” he said, “play it with me.” He picked up his alto, and I swear it was the most amazing musical experience. It was like he pulled this line right out of me. I had no place to go but right with him.

…..All of a sudden, it hit me. “This is how Cherry and Ornette are able to do all that stuff that doesn’t seem possible, exactly together. They aren’t playing metrically consistent, and yet they’re playing hard, fast lines like they’re one person.” It made perfect sense to me. He has some kind of power that allows him to have that effect on you as a musician. You lock into it, and you’re on the track because you go right with him. It truly was amazing.

…..I had to admit that Ornette was not only concerned about the money, selling records, and all the other business things, he was concerned about my musical, spiritual well-being. He was certainly the most generous and kind person I have ever met. He was the only person I have ever known to actually pick up a drunk off the street, take him home, clean him up, and take care of him: help get him back on his feet. He doesn’t give money to the United Way: he picks the guy up off the street. That’s a real fundamental thing about Ornette. He is very direct. That’s why the world is so mysterious to him.

…..Time had passed, and he needed to be more cognizant of how fucked up things are. I am sure he is, but he was always surprised that the world could be a certain way and that he was somehow different. He never understood why he was treated in certain ways.

I needed to catch a cab late at night. He was there, and I had my hands full or something, and he was trying to hail the cab. And cabs are flying by. They had their lights on, but nobody was stopping. I put out my hand, thinking maybe they didn’t see Ornette, and a cab stops. He said, “You see that, right?”

…..“Oh yeah, I see it now.”

…..I deal with that shit every day,” he said. Ornette is a great man. There is no question about it.

..…How’d you lose your job at Horizon?

…..As I said, I originally got involved with Ornette because I asked him to record with Charlie on Closeness. Through that we got to know each other. I told him, “I’d like to make a record with you.”

…..He said he’d just finished a tape that he felt very proud of, but he really didn’t want to let it go. He’d been working on it for three or four years. Eventually, we got together on it. We [A & M] bought that master tape from him: Dancing in Your Head. It was different , definitely a big change in his style; it was considered something of a breakthrough, like it or not. That was a good thing we did. We paid a lot of money for it, but a couple of months later, he sent me back for more money. I went and got it. When Jerry Moss fired me, he said, “You know, towards the end there, Joh, I think you were working more for Ornette than you were working for us.” It was true. I was. I was spending all my time down at his place. I was focusing on his loft problems and his business problems. I never realized that things could be so screwed up in somebody’s life. He just lived a certain way, no lamp shades around Ornette. It was all bare light bulbs.

.

*

.[

.

.

Listen to “Midnight Sunrise” from Dancing in Your Head

.

.

_____

.

.

Excerpted (with permission from the author and UNC Press) from Pressed For All Time -Producing the Great Jazz Albums, by Michael Jarrett

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Pamela Jarrett

Most of Michael Jarrett’s writing on jazz production appeared in Pulse!, Tower Records’ magazine. His day job, however, was professor of English at Penn State University (York Campus). In addition to .Pressed for All Time, his book about jazz record production, Jarrett wrote. Drifting on a Read: Jazz as a Model for Writing; .Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC; and .Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. He is now retired. He and his wife live in the village of Ojochal, on the southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

.

.

.