.

.

…..Drawn from interviews with prominent producers, engineers, and record label executives, Michael Jarrett’s Pressed For All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums is filled with interesting stories behind some of jazz music’s most historic, influential, and popular recordings. In cooperation with Jarrett and University of North Carolina Press, Jerry Jazz Musician will occasionally publish a noteworthy excerpt from the book, which is now available in trade paperback.

.

.

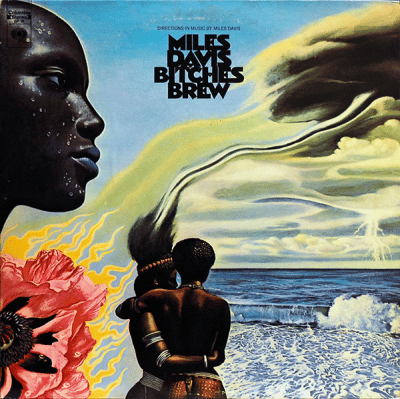

In this edition, producers Teo Macero and Bob Belden, and bassist Dave Holland talk with Jarrett about working with Miles Davis on his groundbreaking 1969 recording, Bitches Brew

.

.

.

.

___

.

.

In addition to being a jazz saxophonist and composer, Teo Macero was a producer at Columbia Records for twenty years, working with artists like Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington, Tony Bennett, Count Basie, and Charles Mingus. He also produced two of the most important jazz recordings ever, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, and Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography.

.

.

Bob Belden was a saxophonist and composer who also worked as a producer for Columbia Records, where, among other roles, he worked on the remastering of recordings by Miles Davis.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography

.

.

Dave Holland is a renowned jazz bassist, composer and bandleader who has been performing and recording for five decades. He played bass on Bitches Brew.

Click here to read his Wikipedia biography

.

.

___

Teo Macero (Producer)

Now and then, Miles got his back up and created some problem. One time, that might have been Bitches Brew, we had a fucking battle in the studio. We didn’t physically fight. He wanted me to fire my secretary. I said, “Fuck you. I’m not going to do that! She’ll do anything for you, Miles. She’ll give you the goddamn world. I’m not going to fire her. She’s a great secretary, and she loves you.”

“Fire that bitch!” He called up the president [Goddard Lieberson] and tried to get her fired. We went at it tooth-and-nail in the studio.

Then, I called up Mr. Lieberson and said, “I’ve got a problem.”

He asked, “Is there anything I can do?”

“No,” I said. “I think I can solve it.” Miles started to pack up to leave the studio. I told him, “Goodbye.” Then he made an about face, came back in, and took out his trumpet. We turned on the machines.

He said, “Come on out here, you white motherfucker.”

“If I come out there, I’m going to fall over you.” But finally, I went out in the studio, and I stood shoulder to shoulder with the song of a bitch for the whole session. I pressed his shoulder against mine. That’s how we made the record.

Sometimes the artists get crazy. I’d say, “Jesus Christ, what more can we do for you?” I got him a million-dollar contract.

When it’s all said and done, though, Miles was very generous. He gave me a big fur coat one time for Christmas. He gave me a lot of gifts.

.

Bob Belden (Columbia/Legacy Reissues)

Let me say, Teo was offered the job of doing all this stuff (i.e, the reissues). He was offered big bucks and a carte blanche. All Legacy wanted was for [producer Michael] Cuscuna and me to work with him, to be kind of like his seconds: [do things like] “That’s not the right title, Teo. It’s this title. That’s not John McLaughlin. That’s Sonny Sharrock. Or that’s not Chick; that’s Herbie.” Little stuff like that. He didn’t want to have anything to do with us. Then, anything we did, he’d call one of us and scream – physically threaten us.

The irony of it was, we all liked the guy. He was a very charming, very intelligent guy, who, unfortunately, made his living as a second banana, but then wanted everybody to go, “He’s the reason why this stuff happened.” More than anything, what he was afraid of was that we’d find out what his whole function was. In some cases he was a major player. In other cases he was just there, along for the ride.

When the decision is made to create a box set around a particular era, a particular time frame, the producer’s first role is to define the period you’re dealing with. In the case of Bitches Brew, we had a choice because, about a year earlier, we had redone many of the LPs from that period on CD for Japan. That gave us a chance to look at all the master tapes. And the master tapes, because those records were so popular, were completely beat up. Actual sections of tape were missing because of oxidation; the magnetic particles disintegrated. You’d look up at the tape, and it would be clear for about a second. When we realized we had some pretty bogus masters, we decided we had to remix and recreate Bitches Brew. That’s when it really got to be a producer’s job.

We tried to adhere to the sound as close as we could: to get the balance and the perspective of the instruments that were on the original. Because of digital technology and the fact that we didn’t go so deep into processland, the sound was made clearer. The instruments are better defined.

The original Bitches Brew was released on LP [1970]. They started making copies of that LP master by 1972. For the most part, what the foreign entities were given was a second-or third-generation copy of the LP master. Then they recopied that copy and made all their foreign masters from that, ending up with fourth-or-fifth-generation copies. The CD that was out [when the reissue appeared] – the clamshell – was from a quad master, and it was a third-or-fourth-generation dump. So albums had no high end or low end.

But what I found out [readying the recording for reissue] was how much of an influence Miles had on the sessions. He was directing the band to start and stop. He was even saying to Teo, “You can put this part and edit it onto this part.” He was telling Teo what to do. For some reason, this record is just a little bit…Miles has got a little more intensity – his focus on it…Bitches Brew is not just about what album was issued. It was really the crystallization of this process he was developing as a composer and arranger.

At that time, because of a lot of the rock ‘n’ roll stuff going on, because Miles’s new wife [Betty Mabry] was laying stuff on him, and because Columbia was suddenly a Nehru-jacket kind of company, I think Teo was able to say to Miles, “This is what’s happening.” Somebody was telling Miles what was really happening. Some people say it was Tony [Williams]. Some people say it was Betty Mabry. Since Miles was not around, I couldn’t ask him. But apparently he got enough information.

I found out through Harvey Brooks that Bitches Brew, the character of that date was set by a Betty Mabry demo, one with [John] McLaughlin, Larry Young, Joe Zawinul, Mitch Mitchell, and Harvey Brooks. Betty was traveling with Miles. She was influencing him. She was hip. Keep in mind, it was 1968. She was way ahead of her time, and she was in over her head at the same time. From that crossover period – from soul and rock – Miles took the rhythm, and he took an element of the harmonic language which was kind of a triadic approach. By the time he got to Bitches Brew he had perverted that triadic approach, and it became this polychordal jungle.

.

Dave Holland (Bass)

Miles would take a tune that somebody brought in, and he might use only the bass line or only part of the bass line. I remember Wayne [Shorter] brought in the tune “Sanctuary,” which had a lot of chord structure to it. And Miles basically reduced everything to a pedal tone that the bass played, a D pedal, underneath everything. And the melody floated over that. So that completely deconstructed the song. This was a technique I saw Miles do many times. There were a lot of pieces that he reworked and did that to and just took a section of it.

.

Teo Macero

I did a concert – the Isle of Wight. It was 1970. Every major group in the world was there in England. I was in charge of recording all those artists: Jimi Hendrix; Emerson, Lake and Palmer; Ten Years After; the Who.

Before they went on, I’d go into this wagon where they were sitting. I used to wear a sweater – very conservative dresser – and everybody would say, “Hey, you don’t belong in here, man. Leave us alone!”

They were smoking some joints, and I don’t know what-the-hell else. I’d say, “Looka here, I’m a producer for CBS.”

“We don’t give a shit, man. Get the fuck out of here!”

“But look,” I said. I’ve got to record you in about twenty minutes. It would be nice if you’d give me some information so I don’t make any mistakes.”

The cat would say, “What do you do, man? Who are you?”

“Well, I work with Miles Davis.”

He says, “You Do? Did you produce that Bitches Brew record?”

“Yeah,” I said. Every rock artist in the world knew that record! So I’d walk in the door: “I’m the producer of Bitches Brew.”

They’d say, “Hey, come on in, man. Sit down and smoke a joint.”

I’d say, “No, thanks. I got too much on my mind. We got three separate crews out there. We’ve been working twenty-four hours a day for six or seven days.”

.

.

___

.

.

Listen to “John McLaughlin,” from Bitches Brew

.

.

_____

.

.

From Pressed for All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums from Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday to Miles Davis and Diana Krall. Copyright © 2016 by Michael Jarrett. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.unc.edu

.

.

___

.

.

photo by Pamela Jarrett

Most of Michael Jarrett’s writing on jazz production appeared in Pulse!, Tower Records’ magazine. His day job, however, was professor of English at Penn State University (York Campus). In addition to .Pressed for All Time, his book about jazz record production, Jarrett wrote. Drifting on a Read: Jazz as a Model for Writing; .Sound Tracks: A Musical ABC; and .Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. He is now retired. He and his wife live in the village of Ojochal, on the southern Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

.

.