Gene Lees,

author of

Portrait of Johnny:

The Life of John Herndon Mercer

___________________

“Moon River,” “Laura,” “Skylark,” “That Old Black Magic,” “One For My Baby,” “Accentuate the Positive,” “Satin Doll,” “Days of Wine and Roses,” “Something’s Gotta Give,” — the honor roll of Johnny Mercer’s songs is endless. Both Oscar Hammerstein II and Alan Jay Lerner called him the greatest lyricist in the English language, and he was perhaps the best-loved and certainly the best-known songwriter of his generation. But Mercer was also a complicated and private man.

A scion of an important Savannah family that had lost its fortune, he became a successful Hollywood songwriter (his primary partners included Harold Arlen and Jerome Kern), a hit recording artist, and, as co-founder of Capitol Records, a successful businessman, but he remained forever nostalgic for his idealized childhood (with his “huckleberry friend”). A gentleman, a nasty drunk, funny, tender, melancholic, tormented — Mercer was a man immensely talented but plagued by self-doubt, much admired and loved but never really understood.

A scion of an important Savannah family that had lost its fortune, he became a successful Hollywood songwriter (his primary partners included Harold Arlen and Jerome Kern), a hit recording artist, and, as co-founder of Capitol Records, a successful businessman, but he remained forever nostalgic for his idealized childhood (with his “huckleberry friend”). A gentleman, a nasty drunk, funny, tender, melancholic, tormented — Mercer was a man immensely talented but plagued by self-doubt, much admired and loved but never really understood.

In Portrait of Johnny: The Life of John Herndon Mercer, music historian and songwriter Gene Lees deals tactfully but directly with Mercer’s complicated relationships with his domineering mother; his tormenting wife, Ginger; and Judy Garland, who was the great love of his life. # Lees’s book is a highly personal examination of Mercer’s life, filled with personal insights only their friendhip of many years could provide.

In quotes taken from an October, 2004 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician contributing writer Paul Morris, and in excerpts from his book, Lees shares his thoughts on Johnny Mercer.

_____

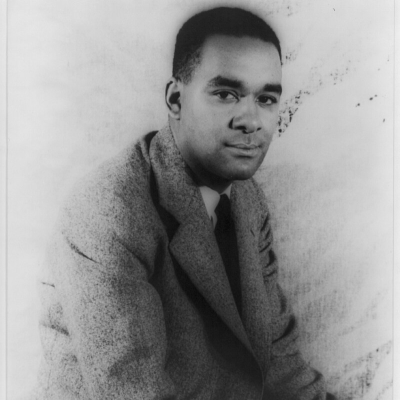

Johnny Mercer

_____

“Too Marvelous For Words”

Youre just too marvelous

Too marvelous for words

Like glorious, glamorous

And that old standby amorous

Its all too wonderful

Ill never find the phrase

That says enough, tells enough

I mean just arent swell enough

Youre much too much, and just too very very

To ever be, to ever be in the dictionary

And so Im borrowing a love song from the birds

To tell you that youre marvelous

Too marvelous for words

______________________

When you are a personal witness to something like Johnny Mercer’s life, you might as well put it down on paper. If anyone in the future wanted information on Johnny, one of the people they would interview would be me. I made the biography personal because it was meant to be personal.

*

Johnny and (childhood friend) Dick Hancock were enamored of the playing of Bix Beiderbecke and Frank Trumbauer — whose early recordings they collected. They were avid, too, for the Paul Whiteman band.

*

Johnny Mercer was a very Southern writer, and many of the greatest American writers have been Southerners. There is a poesy about the South that gets into the writing of a lot of people — Carson McCullers, Truman Capote, and Tennessee Williams among them. Poetry seems to be part of the language of the South, and Johnny grew up with this kind of poetry in him.

Johnny once told an interviewer for a magazine published by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); “I think I always liked music, and probably wanted to be a tune writer rather than a lyricist.” His lack of technical command of music bothered him all his life. And that comment reminds me of something he said in one of our many conversations: “I think writing music takes more talent, but writing lyrics takes more courage.”

*

John was steeped in black culture, and it can be heard in his adult singing. One example: he could crack his voice, a little like a yodel, into octave leaps. He was the only white singer I ever heard who could do that.

*

John was always at the top of his form when he was writing from his own memories and experience. And lyricists are ruthless in their retention of early wistful memories for later resurrection and cold-blooded use as “material.”

John said that (Hoagy) Carmichael was one of his most important teachers. He wrote: “I leapt at the chance to write with Hoagy. He proved an understanding friend and teacher…When I say teacher, I mean just that; he broadened my ability with his knowledge and experience.” But John later also recalled Carmichael as a stern taskmaster: “He is such a gifted lyric writer on his own that I felt intimidated and tightened up too much to do my best work.” This is one of the signs of a relationship that seems often to hve been an uneasy one. But it was a fruitful one.

*

John once told me that Jerome Kern “was hard to work with because his standards were high. With me, it was nothing at all, it was really fun, it was an enjoyable job. Of course, I didn’t work that long with him. I didn’t have a fight with him. If I’d had to write six or seven shows with him and he’d thrown his weight around, I guess he could have been a son of a bitch. But he wasn’t.”

*

Mercer’s lyrics have a deep craft to them, and feature a subtlety about the sonorities of the English language that I don’t think any other songwriter equals. Alan J. Lerner thought he was the greatest of all our lyricists — and I am inclined to agree.

I have come to realize that Johnny must have had an amazing musical memory. Harold Arlen, Harry Warren or one of the others would play a tune for him, and he would get an absent-minded look on his face and leave. There were no tape recorders of any kind in those days to remind him of what was played, and he would just wander away and come back a couple of days later with the lyric. That means he had totally memorized it in one or two hearings.

*

Johnny didn’t play the piano, and he didn’t like to write lyrics before the music. I don’t think our best songs are written that way — with possibly a few exceptions — because of the natural contour of the melody. The composer shouldn’t be restricted by the lyrics. As I said in the book, I believe good lyricists are more able to hear the words in music, whereas the composers are able to hear the music in words.

*

John said of the song “Laura”: “If a fellow plays me a melody that sounds like something, well, I try and fit the words to the sound of the melody. It has a mood, and if I can capture that mood, that’s the way we go about it. Laura was that kind of picture. It was predesigned, because Laura was a mystery. So I had to write ‘Laura’ with kind of a mysterioso theme.”

*

I grew up on network radio, and so did Johnny. It began in 1928, and spread very rapidly until it was the predominant form of entertainment. During the Depression, people had very little money, and radio flourished. Because all you hear on the radio today is rap or rock and roll and so-called “pop” music, the early era of radio has been swept away. But in his era, Johnny Mercer could take a song like “Lazybones” to Mildred Bailey, who would sing it on network radio and it became a hit within a week. That was the extraordinary power that radio had.

*

Radio was also an incredibly powerful force for education, and as a result, people grew up knowing all the names and the abilities of many of the day’s opera singers, symphony conductors, and jazz bandleaders. Around 1949, when advertisers discovered the power of television, network radio sponsors pretty much began to withdraw from radio. As a result, radio became more locally programmed and records became the predominant form of radio entertainment. There is a symbiosis between records and radio, because the record companies wanted the exposure, and the radio people wanted the music. Top 40 radio grew out of this. Local radio has been an incredible force for destruction of American culture.

Quite a number of people have told me how hip they thought Johnny was — or “hep,” as they said in those days. The term “cool” wasn’t even in use then, but if it had been, that is the word that would have applied to Johnny.

*

Jo Stafford told me, “My first memory of Johnny was hearing him on the radio. I had been a fan of his singing from the Paul Whiteman days — he did some things with Jack Teagarden, such as ‘Christmas Night in Harlem.’ In 1936, my sisters and I used to frequent a place on Vine Street called The Famous Door. It had jazz players. It got to be where we were there every night. We got to be the house singers, practically, the three of us. And one night, all of a sudden, there sits Johnny Mercer. I almost went out of my skull. I was such a fan. I went over and asked for his autograph, and he gave it to me. And at that time he didn’t just sign his name. He had about a five-line sketch of himself that he did. And it looked just like him. He would draw this little caricature and sign his name. I still have it.”

I used segments of (his unpublished autobiography) in my book. After he died, I edited it for his wife, and I found some of it to be very interesting. When I read the manuscript I could hear him talking, because I remember how he talked. I wanted to retain for the reader a certain flavor of his speech, and I think that is one of the reasons I used it. Not all of the autobiography is worthwhile, and it isn’t very well organized, but I found some of the stuff quite fascinating.

*

Concerning John’s affair with Judy Garland, the composer Hugh Martin said, “I think they were always attracted to each other, and they couldn’t resist. And neither of them had a very high moral account.”

Everyone I interviewed who knew John well would begin his or her comments with some variant on: “Well, you know, John drank.” No kidding. His friends exchanged stories about his drunken insults. One that I heard involved a prominent actor whom John insulted at (as usual) some party. He said, “You never could act! And, what’s more, you’re too short!” And he took a swing at the man, who, in response, gave him a push, sending Johnny sprawling. the next day, the actor, feeling remorse for the incident, called Johnny and apologized. John said, “Oh, it’s all right. I thought you were Alan Ladd.”

*

James McIntires’s wife, Betty, said, “{John and wife Ginger} used to come to our house on New Year’s Eve. I always had a New Year’s Eve party. And of course we were all pretty drunk. I went over and started talking to Ginger, and I said, ‘Oh, it’s so wonderful to have you in Savannah, blah blah blah.’ And she was just crying! I said, ‘Ginger, for heaven’s sake, what’s the matter?’ ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘Johnny is so rich and I just don’t know what to do with all this money.’ She had on a dress that must have cost even in those days maybe two thousand dollars. She started to wipe her eyes with this exquisite dress, and i said, ‘Pull yourself together, girl. I’ll help you spend it.’ ”

In many ways, Capitol Records was the expression of the tastes of one man, Johnny Mercer.

*

Capitol Records was founded during World War II under almost impossible conditions. For example, you couldn’t get shellac to press the records on, and everybody said you couldn’t buck the three major popular music labels — Columbia, RCA/Victor and Decca. Johnny was of the opinion that the West Coast had all this talent — especially in the form of singers in movies — who never got to record. He and Los Angeles record store owner Glenn Wallachs got together and went to Paramount Records producer and songwriter Buddy de Silva — who invested several thousand dollars — to start Capitol Records.

*

Johnny signed Nat Cole to Capitol immediately, and he made his own first records, one of which was “Strip Polka,” a really cute, humorous, gentle and funny song. Then he signed all kinds of people, including singers who were in film, like the movie star Betty Hutton, Johnny Johnson, and others. He also signed Stan Kenton to the label. You talk about Johnny being the “hippest” in the thirties; I was in high school when Capitol Records was founded, and I thought these were the “hippest” records you could get. They were marvelous recordings for their time, and they still are, many of which are still available.

*

Capitol Records was instrumental in Peggy Lee’s career. She married and had a baby daughter, and didn’t want to sing anymore. Capitol approached her about recording a few songs they wanted to put on a 78 rpm album Dave Dexter was producing called The Capitol Jazzmen. She thought all she would have to do is go down to the studio and record one or two tunes, and that would be it. She sang “That Old Feeling” and a blues called “Ain’t Going Nowhere.” After these recordings her career was re-launched, and she became one of the biggest sellers on the label.

*

Johnny’s judgement of what and who would sell seemed infallible, with one exception: Paul Whiteman, whose career had faded and whom Johnny probably signed out of gratitude and loyalty.

*

Mercer was one of Capitol’s major artists. An interesting thing about him is that he never thought of himself as a success as a singer, yet lots of people were crazy about his singing. As a matter of fact, if you listen to Frank Sinatra, Jr, you will find that he doesn’t sound like his father, he sounds like Johnny Mercer.

*

Capitol was the first label to package books and records together specifically for children. The first one was Bozo the Clown, and they also did some records with Margaret O’Brien. That division of the company was a huge success. In the forties, it seemed like Johnny was incapable of making a mistake.

*

He eventually lost interest in Capitol. As he told several people, including me, it simply got too big. When Capitol was a little label, he could listen to everything and supervise all this stuff. He loved Capitol, but not after it got to be a giant corporation.

*

Johnny had a nightly radio show called the “Chesterfield Supper Club.” Before going on the air, they would hand him the day’s newspaper. After about ten minutes of reading the headlines and the stories, he would sing a blues, telling all the news of the day. The segment was called the “Newsy Bluesies.” It was astounding how he improvised blues lyrics.

*

Johnny would listen to every song that came across his desk. He gave time and respect to everyone who brought him a song, and as a result, he discovered a lot of people, “Moonlight in Vermont composer John Blackburn being one of them. He only wrote that one song, but it was a pretty good one.

_____

Mercer was incredibly generous with other songwriters. Instead of being petty or jealous, he encouraged them. He even encouraged Peggy Lee to write lyrics, and she wrote very good ones. He helped Carl Sigman, who wrote the lyrics to “What Now, My Love?”, and he encouraged Livingston and Evans (“Que Sera .Sera”), whose first success was through Johnny.

_____

I have some theories concerning why he and Broadway didn’t click. Alan Livingston, who became president of Capitol Records, said that Johnny was almost incapable of saying “no” to people. Somebody said that he wrote with whatever songwriter got to him first thing in the morning. Consequently, he wrote with a few second-rate musicians who were far below his standard, when he should have been writing with people like Jerome Kern.

*

He wanted desperately to write for Broadway, but he got involved in a group of shows that had very weak scripts — and you can’t patch up a bad script with a good song. It just can’t be done. Not one solid Broadway script was ever presented to him. The best was probably Lil’ Abner, which was a moderate success, but most of his shows on Broadway were not successes, and he was very acutely aware of that failure.

By the 1950s, John’s output of great songs almost dries up. Bill Haley and the Comets had a 1953 hit called “Crazy, Man, Crazy,” and then a succession of hits, including “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” in 1954. “Rock Around the Clock,” which became a hit in 1955, ultimately sold 2.2 million copies. The age of rock had come, and if John did not forsee the scope of social and musical change that was under way, well, neither did anyone else.

*

On the evening of March 14, 1971, Johnny and his work were featured in the “Lyrics and Lyricists” series produced at New York’s Ninety-second Street YMHA by Marice Levine. He sang a condensed medley covering much of his career, accompanied by pianist Richard Leonard. The results were released on an L.P. It is available today (on CD) on GRP Records. And it’s astonishing. Hearing one after another of his works, in his own performance, one is blinded by the brilliance of his writing. He was everything other songwriters thought he was. The rich and often wildly funny ingenuity of his rhyming — and in our rhyme-poor language of English — will leave you with your mouth agape.

_______________________________________________________

Portrait of Johnny:

The Life of John Herndon Mercer

by

Gene Lees

*

About Gene Lees

Gene Lees is the author of fourteen previous books of jazz history and analysis, including The Modern Rhyming Dictionary: How to Write Lyrics, a standard reference work. He has written biographies of Woody Herman, Oscar Peterson, and Lerner and Lowe. As a lyricist, he has collaborated with Antonio Carlos Jobim, Charles Aznavour, and Bill Evans, among others, and his songs have been recorded by such artists as Frank Sinatra, Carmen McRae, and Tony Bennett. A three-time winner of the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award and a recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Jazz Journalists Association, Lees writes and publishes Jazzletter. He lives in Ojai, California.

Johnny Mercer products at Amazon.com

Gene Lees products at Amazon.com

A data base of Mercer’s songs, from the Georgia State University Library

_______________________________

This interview took place on October 6, 2004

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Hoagy Carmichael biographer Richard Sudhalter

_______________________________

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

# Text from publisher.