Scott Shachter

Scott Shachter has been a professional musician in New York since the 1980s. He’s worked with some of the most talented performers in the world — among them, some of the most neurotic.

Through it all Shachter has been a storyteller. Outside In, his first novel, was inspired by his encounters with immensely talented performers who seemed unable to relate to anyone, as if they were separate life forms. This jazz fiction/speculative fiction/comedy puts the reader inside the wacky life of a working class musician, and explores the “crazy genius” in us all.

With the publication of this first novel comes great creative achievement in the face of a volatile environment for unpublished authors. The publishing model is no longer what it once was, creating more potential uncertainty — and opportunity — with each technological advance.

In this June, 2013 essay, Shachter shares many of the creative and business challenges he had to overcome before his first copy of Outside In was pressed. It is a story many of our finest writers share today — that of remaining authentic in spirit and vision in a world where formula is most often rewarded.

Outside In: A Jazz (and Writing) Odyssey

By Scott Shachter

__________

Imagine you are standing on the lip of a nightclub stage, blowing into your saxophone. Behind you is a rhythm section, a piano, bass and drums swinging fervently. The mildewy club, like a dark, small barn full of booze, is in the worst part of town, the owner barely paying carfare for tonight’s two sets. But as you blow, as you improvise directly from your soul, you’re reminded once again this is the music you were born to play. Your heart stirs your freshest ideas through your fingers and wind, your saxophone resounding through the bodies in the tight-packed space. These are the best sounds you’ve ever made. The dusty air now tingles—you can feel it—as if the universe is pleased. But there is just enough light to see disappointed looks. Even your rhythm section wants you to stop. The drummer wishes you’d sell your horn. The club owner is grimacing: He wishes you’d give back the carfare.

In my new novel, Outside In, the most innovative art is a force surging beyond the culture. It can peel open other worlds, even bend the fabric of space. In fact, spontaneous invention just might sing to the outermost reaches of the universe. But the artist’s dream often dies when it crashes into real life. When Shawn, a hard-knocks New York saxophonist, forgets his society gigs’ musical etiquette and blows one avant-garde solo after another, he feels the Earth “nodding with him, the air shimmying, the stars flickering with every note”—while the bandleader wants to strangle him. Shawn can’t help himself. His “outside” jazz is his calling, though it irritates everyone else, including Carole, the woman he loves. Unbridled expression is often raw and disturbing, even for its creator. This story is about the collision of Shawn’s art with his love, a tour from madness to the sublime.

Shawn’s jazz teacher and hero, Wendell Rice, urges Shawn to develop his own unique voice. Wendell says the secret to happiness is finding the one thing that makes you special. “It’s all that counts, Shawn—putting the one thing in the music. Find the one thing; find it, Shawn, so the Heavenly Voice can sing through your voice—like it has for musicians since the beginning.” Sound can be a vessel for Heaven. When Shawn taps the creativity field on the edge of human consciousness, the “Outside dimension,” he hurls full throttle into “crazy genius.”

Carole, a stunning nurse devoted to the tangible here-and-now, just wants Shawn to return to the simple, sweet man she’d loved. But the more relentlessly he fakes being “normal” for her, the crazier he seems. Normal is impossible once your soul is in tune with the Outside dimension. And the more Shawn bonds with his unearthly connection, the more help he gets from the most eccentric and powerful sources. As his grip on reality shatters, his jazz becomes spectacular.

* * *

Sharing your artwork is brave. Children can’t wait to show what they just drew, and everyone cheers. But if you’re a middle-aged man showing off your sloppy stick-figure masterpiece, your friends will demand you seek help. Writing a first novel at this point—I’m now in my fifties and with a full schedule—is brave and a bit crazy, but I felt I had no choice. In fact, I’d do absolutely nothing if I felt I had a choice.

I play thirteen woodwinds—mostly flutes, clarinets and saxophones—not because I’m a glutton or a masochist, but because I fell in love with each one’s special sound and had to play them. I felt I had no choice. Fortunately, this led to gigs. And if I were to keep getting those gigs, I had to stay good on all those instruments. No choice. I play mostly Broadway shows. I’ve been a regular or a sub in the pit of nearly 70 productions, generally playing between three and five instruments on any given show. At How to Succeed in Business I played six. At High Society I played seven. I’ve played in some well-known orchestras and big bands, chamber orchestras, small groups of all kinds, and performed most every style of music. I also teach privately, compose and arrange my own music, and even customize mouthpieces for my wonderful, prestigious colleagues (I have to say that in case they read this.). Each endeavor is worthy of my full commitment, so I’m always diving into more than I can do. No choice. If I didn’t feel compelled to honor all these paths, I’d be the giddiest, most professional bum in NY.

Today I played a matinee at Annie, a superb production, but to get there I had to walk through the Puerto Rican Day Parade. While I’m sure it’s a charming celebration, I had to negotiate five instruments and equipment in midtown Manhattan through thousands of wild revelers and their ear-splitting salsa bands. I had to: I had to honor my job, my commitments. But I don’t long for constant fireworks. I’m not one of those fidgety people you see with their cell phone to their ear, their crossed leg bobbing, a coffee in one hand, a Sudoku in the other. Today I would’ve preferred to stay in bed—I think all day—but “honoring” always wins.

Writing a novel meant ten years of carving spare time for a book that might never be finished or ever get read. But my story’s dream had bitten me in the heart. I had to honor that. And I’d have to be brave: Anyone who’s received a blistering review for something they’d spent years perfecting, knows what it feels like to get a knife wound to the spirit. My favorite authors gave me inspiration, but when I listened to my albums, especially Miles’s Kind of Blue, I had my answer. Every solo, every moment of a Kind of Blue proclaims that the soul’s art is worth honoring. I had no choice.

My premise for Outside In started with an idea about “crazy genius.” M-theory contends there are eleven dimensions. I wondered if a few “psychotics” might be perfectly normal except for their talent to perceive hidden dimensions. I wondered if their perceptions, their “delusions,” could be catching. What if a failed musician caught those delusions and they helped his playing—helped so much he became a phenomenon?

I started writing and couldn’t stop. The story poured through me, not in neat, perfect sentences, but in a torrent of comic scenes and characters with multiple, jumbled plot lines. It was an exploding, gargantuan mess of creativity, and before I knew it, I had to honor something way over my head—just like always.

I’d enjoyed writing in high school and college, and through the years I’d kept it up—but just for myself. You can think you’re pretty good when your art is just for you. But now I was about to be the middle-aged man showing off his sloppy stick-figure novel. I might as well walk around drooling, wearing my clothes inside out—unless I could learn the writing craft the way I’d learned all those instruments.

I found a master writing teacher and studied hard. I had no choice but to learn how to write with clarity, tone, rhythm, pace, hooks and except for the next sentence, economy. I learned about showing more than telling, while carting my instruments and books, manuscript pages jutting out of a shoulder bag, reciting lines into the midtown air. I studied how to create strong and truthful characters destined to clash. This came naturally: My whole life is surrounded by characters destined to clash. I learned about creating a dreamworld consistent within itself. And much like music, I studied maintaining a thread and developing it to the point of a high-stakes climax that spells out the underlying theme.

I had some great woodwind teachers, but I’ve learned more by listening to talented players. While there are essential books on the art of fiction, nothing replaces reading novels. Reading the superstars is necessary, but reading less careful writing is brilliant for showing you what not to do. Overall, the best thing I learned was to create from my most genuine voice—the very same goal Wendell has for Shawn.

I had no idea how my unruly tome should end. I used no outline. Instead, I sensed my plot should develop like a work of music. Outside In should flow like jazz. The characters and their goals would drive the action, like Cannonball trading fours with Trane. Of course, the readers of my novel might now tell me they’ve experienced none of what I’m saying here, that I should seriously calm down and get some therapy. This is scary because I think I hear them right now, and there’s no one else in the room. No, sorry . . . just my ears ringing from this afternoon’s salsa wars. The point is, all writers genuinely love their characters, including the evil ones, and there’s a great thrill in giving them the life and power to alter a story’s path. In other words, my characters came alive. They were real to me. Their independent voices and relationships to each other had merged into a unique world. Kind of Blue is chock full of competing styles, but the musicians’ synergy creates its own singular trance. My characters were so real to me I used to dream about them. I’d find myself worrying about them—all the time. I still do. I should call more often, see what they’re up to. I hope they’re okay . . .

Writing demands constant revision. Anything can be said better. Picture me in the Broadway pit of 42nd Street, frantically writing during dialogue scenes. The conductor is looking at me quizzically, wondering if I’ll pick up my instrument in time. The pages in my lap go flying as I scramble to play my soprano sax to his downbeat. The book is always on my mind, interrupted only by life. I’m now writing on the train coming home, now writing past 4 AM at my computer, now writing first thing in the morning (late morning for everyone else). And all of it that night and day is about just one paragraph, maybe one sentence—one I’ll eventually cut.

After ten drafts, not counting a few minor run-throughs, my teacher and objective readers urged me to send the book to literary agents. The typical method is to research and query the appropriate agents for your genre. Learn as much as you can about their tastes and about the books they’ve helped. I submitted to fifteen agents. Some authors submit to hundreds before they finally get accepted. Fifteen, they’d say, is hardly getting started. Of the fifteen, five never responded, eight replied with a cold, form-letter rejection and two were interested enough to request the entire manuscript. After several months of waiting, they both said no. One thought it wasn’t “hard science fiction enough,” and the other liked everything but the science fiction parts. I was depressed.

Should I take out all the science fiction and make it a love story? It could be about a starving sax player and the woman who wanted him but didn’t want to be poor. Agents might like this, especially if I included all the horrible gigs I’ve actually played—and the women I’d chased who didn’t want to be poor. It would certainly be truthful. On the other hand, should I turn the whole thing into an epic vampire saga: vampire big bands, vampire divas, werewolf conductors, drummers with eight legs like giant spiders? Oddly enough, this too is not far off from some gigs I’ve played—or some women I’d chased.

It didn’t elude me that the agent ordeal was challenging my biggest theme of Outside In: “trusting your muse.” I had no choice but to stick with it. For me, playing music from the soul is never going to be “hard science fiction,” but the magic within the notes is inescapable. I submitted the novel to two contests. It reached the quarterfinals in the 2011 Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award and won Honorable Mention in the 2011 Leapfrog Press Fiction Contest. Then I put it aside for over a year.

I would’ve much preferred landing an agent and a publisher, and let them take care of the rest. As I’ve said, I’d do nothing at all if it weren’t for all the honoring. In fact, when something in our home breaks, I leave it alone and hope it comes to its senses. But the traditional agent path is no guarantee of publication. Not every agent is as dedicated as they pretend, and not every one of them sells the manuscripts they take on.

Today it’s easier than ever to self-publish, yet there are two reasons I didn’t want to go through with it (three, if you count my underlying sloth): The distribution is entirely up to you, which means marketing. Yikes. And self-publishing used to always be unprofessional—shlubby. But when a friend who’d read my manuscript prodded me to just “get it out there,” I reconsidered. I realized distribution was not my first priority and that I had the potential to put out a product every bit as professional as one from the big houses.

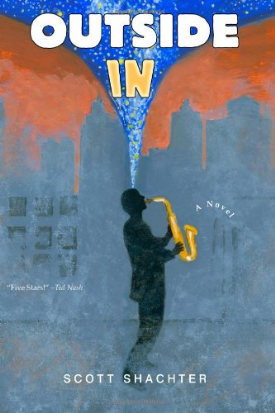

The first thing I did was hire a publishing consultant. She locked me into CreateSpace.com, an ideal self-publishing service. Self-publishing is big business now, so it’s easy to find a consultant or a how-to manual. CreateSpace is more than happy to supply you with whatever you need, from consultants to editors to designers. I was lucky with the designer question because I happen to be married to one, Lisa Sloane (lisasloanedesign.com and lisasloane.com). Lisa is also one of my favorite artists. She painted for me an exquisite cover and designed the interior precisely as I’d imagined it.

I’m at a point in my life where I need my art to count for something. I wish my novel had been published by a big house and mass marketed, but at least it’s the story I wanted—unmanipulated by someone else’s version of what will sell. Just knowing that perhaps a few hundred people will read my story as I’d imagined it directly from my heart, means everything.

Kind of Blue ends but never really ends. The last tune, “Flamenco Sketches,” is like a meditation that takes the listener to jazz heaven and leaves them there. I’d love that to happen for Outside In readers, that the music of my words, of Shawn’s journey, could lift people even long after they’ve finished reading.

If you have an unusual story to tell, you owe it to yourself and the rest of us to tell it. Don’t let anyone’s cynicism or jealousy of your dream tear you down. You can submit to agents and perhaps do better than I did. You can always self-publish, which is occasionally the minor league path to a first-rate publisher. Don’t let your great story die. Be like that sax player wailing for the universe.

* * *

To learn more about Outside In and to hear my original music—none of it avant-garde—please visit my website, www.scottshachter.com. To purchase the book or to see the enthusiastic reviews, please visit the Amazon page at http://www.amazon.com/dp/0988459906

Scott,

If your novel approaches the clarity and passion of your post, it will find an audience. I will look to your website to hear your music as well. Just as a “free jazz” player must suffer those who cannot or will not hear what is in the players’ soul, so too will many publishers and readers. But then this book, or song is not for them.

Your references to two of Miles’ finest moments is illustrative of you as a musician and as an author. I know that the whole marketing thing is a painful task for any artist. My wife is a painter and bemoans having to do any part of it. I urge you however to look to how social media can get your work in front of many eyes. I would be glad to share with some of the jazz writers and social media types that I know are active in the medium. Please let me know if I can be of any help.

I look forward to reading your book.

Regards ,

Bill

Hi Bill,

Your thoughts are beautiful and much appreciated! I’d value your reaction to OUTSIDE IN. You can easily get in touch through scottshachter.com. And I’d cherish any help spreading the word through any “jazz writers and social media types.” If you have a jazz critic/writer friend you’d recommend sending the book to, please let me know. I’m waiting for editorial reviews from some renowned ones, hoping for more good quotes to help with advertising. I’ve got some great ones on the Amazon page, http://www.amazon.com/dp/0988459906, but I think I need Ira Gitler or Nat Hentoff, people like them, to put it out stronger. Then I think I can invest more energy in social media. Your wife sounds like my wife Lisa and me. And Lisa is also a painter. Please stay in touch. Let me know what you think of my music. I’m soon to record another, this one on 13 instruments.

Very Best,

Scott

Wow, I am going to buy this book (when I get some $ together that is) – looks great! Keep up the great work!