I have been fortunate – thus far – to have avoided the many summer colds going around this season, but I have been afflicted, once again, by “Miles Fever.” Every so often, I am struck by an irresistible urge to dig into the catalog of this artist so present during virtually every season of my life, and rediscover the thrill of his sound, and of his cultural significance.

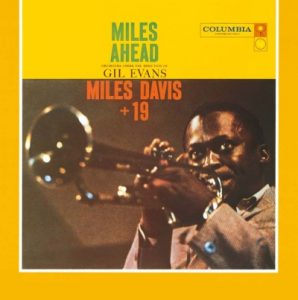

I contracted the virus this morning, and spent the morning (in bed, of course) listening to Miles Ahead, the 1957 recording featuring Miles Davis and 19 musicians under the direction of Gil Evans – his first collaboration with Miles since the Birth of the Cool sessions of 1950, and one of his earliest recordings for Columbia Records. An early example of “Third Stream” music – a term coined by composer Gunther Schuller to describe the fusing of jazz and classical music – the record continues to sound brilliant, with Evans’ cool arrangements setting a rich landscape for Miles to perform in; at times his flugelhorn is utterly romantic, at others it attacks with energy, humor and fire. It is, as the most eminent jazz writer Gary Giddins wrote in Visions of Jazz, “peerlessly seductive.”

With Miles’ blessing, he was marketed by Columbia as an artist who could appeal not only to jazz fans, but also, according to George Avakian, the storied Columbia executive who signed Miles to the label, “people who know nothing about jazz.” In his contributions to the album’s liner notes, Avakian writes that while Miles Ahead is “significant from the musical point of view, it is also an album which we feel is a delight to anyone.” Giddins wrote that the recording is a “commercial and critical landmark in the music of the ‘50’s.”

The back story to this record is the album cover itself. Giddins writes that “the only drawback [to the album] was the cover – a sailboat against a blue sky, intended to express the idea of Miles forging ahead, with a blonde model on the boat. Davis protested, ‘Why’d you put that white bitch on there?’ But the company wasn’t about to burn the 50,000 jackets already printed.” Subsequent pressings of the recording have featured a rather bland photograph of Miles playing his instrument.

I have hosted several discussions with prominent Miles biographers/historians over the years, and excerpts from two of them – with Gerald Early and John Szwed – are found below. You can read the interviews in their entirety by clicking on the links found within the excerpt.

_____

From a 2001 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with cultural critic Gerald Early, editor of the book Miles Davis and American Culture.

Read the entire interview by clicking here

Gerald Early

_____

JJM You said in one of your essays that he was a “man that was not afraid to be himself.” A musician told Ebony Magazine, “Nobody in the world can play music as beautifully as he does and not be a beautiful person inside.” Others would characterize him as being everything from a mysogenist and angry to sentimental and friendly. Who was Miles Davis?

GE As with any complex person, it’s hard to definitively say he was this way or that way I would have to say in the end, Miles Davis was a musician. He was a jazz musician, he was a great musician, who was quite dedicated to his craft, and quite dedicated to the art of making music. He was someone who was very dedicated to expressing himself and his inner feelings and emotions. As an artist, he was a very sensitive man. Artists do lots of things, and I think we tolerate certain kinds of behavior from a great artist like Miles that we would not tolerate from an ordinary person. This is true even when we think of the behavior we tolerate from a great athlete. From great people we tend to tolerate certain kinds of lapses that we don’t from others. Regarding the mysogeny and some of the other things, these are things that were part of his personal life, and his relationship with women. I am not saying that people can’t talk about it – Davis himself talked about it pretty graphically in his autobiography. In the end, the quality of his music and what he produced transcends anything about what he was personally, which I think is true of any artist, whether you want to talk about Mozart or anyone of that magnitude. If you read some of Mozart’s letters, he talked in quite derogatory language, so you can find out about the lives of a lot of people if you dig deep enough, and you find out that they may be a little weird or off center. To some degree, I think all great artists are like that. It’s kind of like what Alfred Hitchcock once said about great actors, something to the effect that great actors are sort of nutty people, but the only way they can do what they do is to be the way that they are. I think that’s really true with someone like Miles Davis. I think the only way he could play the the kind of music he played was to be the way he was, so you kind of had to take the whole package. In the end, what could be said is that he was a great musician, very dedicated to his music and was someone was a very adventuresome musician who wanted to try all the time to experiment in the spirit of jazz, explore and try to do new things. I am not saying that everything he tried worked, or that everyone should like everything he did, but I think the spirit of what was driving him most of the time, whether you liked it or not, was most admirable and what we most appreciate and love in an artist. This need of his to push boundaries and explore is what we most admire.

JJM To say the least, he was a special artist, and I suppose we put up with behavior of his whether we were fans or peers. His behavior, in truth, impacted very few of us. What struck me about him was that he was a “man’s man.” He modeled himself after Sugar Ray Robinson, and he loved boxing, fast cars, and drinking. He led this sort of Playboy existence. What was his concept of masculinity and how did it appear in his work?

GE Yes, he was very much a “man’s man.” He exhibited a lot of those qualities – the way he dressed, the way he carried himself. As you said, his model was Sugar Ray Robinson, a boxer. He admired prize fighters a lot, and he really liked the sport. He comes across as being a tough guy, and I think a part of the reason why he cultivated that kind of persona was because he was a small man, and I think in some ways he wanted to project a physical presence so people wouldn’t take advantage of him because he was small. Also, I think that as a black man he wanted to project a certain kind of toughness, because, once again, he didn’t want people to take advantage of him. Remember, a good portion of his audience was white, a good deal of the jazz press is white, so he was dealing with a lot of people he was skeptical about – if not downright hostile about. People that he would feel uneasy about trusting. After all, they were white people, and he didn’t have any particular reason to trust them in a lot of ways.

JJM One of your writers, Eric Porter, said that Davis “represents the survival of African-American male genius.” I am sure Davis took it upon himself to maintain his esteem..

GE I think very much so, yes. Another reason for him to have this “man’s man” toughness is because the jazz world, particularly at the time he entered it, was connected to the “seedy” side of life. Jazz was played primarily in night clubs, there were prostitutes around, organized crime, drug addiction, and this sort of thing. So jazz musicians, unlike other kinds of artists who are removed from that world, bumped heads with the lower aspects of life. I also think that Davis developed the kind of attitude he did because he was so exposed to this underworld sort of life that bumped up against jazz, particularly at this time in its history.

JJM What were his politics? How politically active was he?

GE He was never really very politically active. From all indications in his autobiography, it didn’t appear he was particularly political. I don’t even know if he ever voted. During the civil rights movement, he gave a couple of benefit concerts, but he didn’t get involved in it the way Max Roach did, or some of the other guys. He wasn’t somebody who got into a big race pride thing like John Coltrane or Pharoah Sanders, or some of the other people who were playing the avante-garde stuff back in the 60’s. He didn’t seem to go that way. On the other hand, even though he didn’t espouse any sort of politics, he came across to the public as being this very uncompromising black man, the sort of guy who didn’t take shit from people. That really impressed a lot of younger black people who came up and who admired him.

Read the entire interview with Gerald Early by clicking here

_______________

Excerpted from a 2003 Jerry Jazz Musician interview with John Szwed, author of So What: The Life of Miles Davis.

Read the entire interview by clicking here

John Szwed

_____

JJM As you point out in the introduction to your book, there are already several biographies of Miles Davis, as well as his own autobiography. What did you hope to accomplish with So What?

JS It started when I ran into Miles Davis’ brother Vernon, and when he encouraged me to write, I was unable to resist. I began talking to other family members, his first wife Irene, his son Gregory, and many of his girlfriends along the way. I then found the original notes from Alex Haley’s interview for Playboyin 1959, and discovered there was quite a bit unpublished material in it. I researched biographer Quincy Troupe’s interviews and found material that shed new light on things. To me, that meant that there must have been inaccurate information in interviews over the years because things kept getting repeated that Miles insisted weren’t true, yet they were being copied from one interview to another when he apparently wasn’t too cooperative. So, that was the reason that I started doing this.

JJM What was a significant childhood event of Miles Davis’?

JS I think he had a very uneventful life as a child. It was almost archetypal. He was raised in an integrated neighborhood and fit in very well with it. There is a story about Miles being chased by a white man going after him with a gun, but he denied it. He seemed to have a quite normal childhood.

JJM You wrote that the thing he talked about with much fondness was his paper route.

JS Yes, that was the only day job he ever had, actually. He took a lot of pride in that, and since he had a sizable allowance, he was free to spend money earned on this job any way he wanted. He would buy clothes and records with it.

The most critical moment of his childhood was his parents’ divorce. That affected him, as it would anyone at that age. His parents had quite a volatile relationship, although not as bad as some like to make of it. For example, there are stories of how his father repeatedly beat his mother, but there is no evidence of that. To take the leap that people have taken and glibly say that Miles modeled his own behavior after his father’s, I see no evidence of that.

JJM Was he embarrassed by his middle class background as he moved to New York and began hanging out with musicians who didn’t have such a privileged childhood?

JS I don’t think ’embarrassed’ is the right word. He certainly told everybody he had money, and he showed it, buying suits and loaning money to people. He bragged about his father’s wealth and about going to Julliard, so I don’t think he was embarrassed by his background. He did want to mix with the “lower depths,” which at the time was a middle class “beat” sort of phenomenon. He did that, even to extremes, but I never saw any evidence of him hiding anything. He was very open about attending Julliard, which was one of the great music schools in the world, and made a point of sharing his lessons with people. His characterization of Julliard in his autobiography was a bit strange. He trashed it in one paragraph, then a few paragraphs later he bragged about studying there. But that very well may have been the way he felt.

Read the entire interview with John Szwed by clicking here

Miles was magic …

Miles was magic …