_____

I am saddened to read of the passing of journalist Nat Hentoff, who died yesterday at the age of 91. Hentoff’s work was published by the Village Voice for 50 years, and was also frequently found in the New Yorker, the Atlantic Monthly, the Wall Street Journal, and Jazz Times. He was also editor of Downbeat during the mid-1950’s. There are many obituaries available to read about Nat and his career – including Robert McFaddin’s in today’s New York Times.

As I began publishing original content on Jerry Jazz Musician in 1999, I had the privilege of having my site embraced by the three most prominent jazz writers of the time, Gary Giddins, Stanley Crouch, and Nat Hentoff. All three of them got involved in Jerry Jazz Musician in their own way.

Giddins — who I was able to catch up with during a recent trip I took to New York — and I developed an interview series called “Conversations with Gary Giddins” that gave readers a window into Giddins’ renowned critical intellect. Crouch appreciated my work called “The Ralph Ellison Project,” an interview series with Ellison scholars that examined the Invisible Man author’s cultural impact. He introduced me to Albert Murray and ultimately contributed several conversations to my site, including one, “Blues For Clement Greenburg,” which was published on the heels of his controversial 2003 firing by Jazz Times. One time he even plugged Jerry Jazz Musician on a CNBC show hosted by Tina Brown.

Hentoff was introduced to Jerry Jazz Musician in 2001, when his 1986 memoir Boston Boy: Growing Up with Jazz and Other Rebellious Passions was being reprinted. In his interview with my friend Paul Morris – a freak for the Voice since his boyhood – Hentoff talked about his youth (including the political radicals in his neighborhood and his work on radio station WMEX) and his early connections with jazz musicians and the associated culture. It was a memorable interview and one that gave Jerry Jazz Musician credibility with early readers and other prominent writers.

In the ensuing years, I had reason to contact Nat at his home office on several occasions. Even though he encouraged my every phone call, each time I called I knew the chances were very good I would get my head taken off the minute he answered. “What is it man?!” he would grumble impatiently. Or, “I am on deadline! What do you want?!?” I would do my best to communicate my needs under those circumstances, but ultimately it would lead to another attempt at another time with another set of sweaty palms.

Despite his apparent cantankerous personality, his heart was always in the right place with me. One time, I invited him to participate in a phone call with James Moody and myself about Dizzy Gillespie. Not only did he take part, he wrote about the call and Dizzy in an ensuing Jazz Times piece. When he turned 80, he proudly allowed Jerry Jazz Musician to celebrate it with an interview — “Civil Liberties: Past, Present, and Future” — that covered many aspects of his career. (When the interview was published, he had me make hard copies of the interview off the web and mail them to his office, insisting on a permanent printed record of it). After Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, I called to ask permission to use some the text from his classic story of jazz and New Orleans (co-written with Nat Shapiro), Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya: The Story of Jazz As Told By the Men Who Made It. He let me use more than “some” of the text – he allowed me to use what was my ultimate hope – all of chapters 1 – 5. “What is the cost for my doing so?” I asked, knowing damn well any amount was more than I could afford. “Nothing!” he pronounced proudly (but impatiently in his classic way). I thanked him over and over before he (politely) hung up on me.

I was perhaps most proud of his description of Jerry Jazz Musician in the Jazz Times piece on Dizzy. “Of the jazz Web sites I visit,” he wrote in his September, 2004 column,” the most far-ranging—and therefore, most often surprising—is Jerry Jazz Musician. The Web site encompasses what could be called American civilization with jazz as the centerpiece.” To have someone of Hentoff’s stature “get it” and broadcast to his readers in such a fashion meant so much to me at the time. He was particularly intrigued by my vision of combining jazz and politics, and would often encourage me to publish a book collection of interviews with authors I had interviewed, even to the point of introducing me to his agent. Hence, the real world (meaning the need to earn a living) caught up and nothing was ever done with that encouragement.

In my “Civil Liberties” interview with him, I asked Nat what he still hoped to accomplish in his life. “…as long as I have a typewriter,” he said, “and a place to get published, I am happy…I feel lucky to have been able to do what I wanted to do. One of my favorite songs is Ellington’s ‘What Am I Here For?’ and I feel as if I know what I am here for, which is to write about what I most enjoy, as well as what I most detest.”

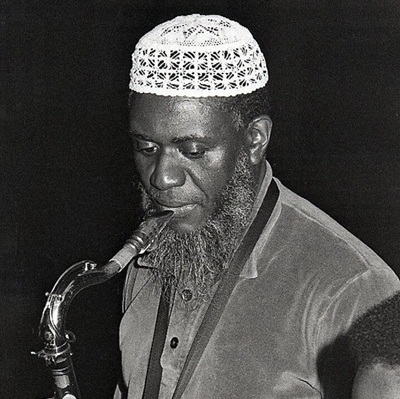

Nat Hentoff (date unknown)

A beautiful article and moving tribute to one of my heroes. Thank you! Nat H was one of my primary influences.