.

.

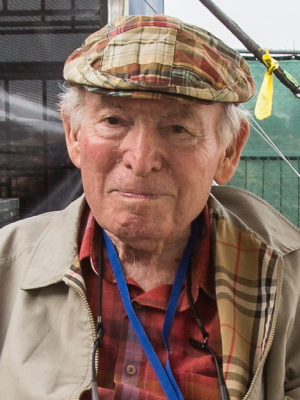

George Wein (in a photo from 2014)

author of

Myself Among Others:

A Life in Music

,

.

___

.

No one has had a better seat in the house than George Wein. The legendary impresario has known some of the most celebrated figures of jazz — from Duke Ellington to Count Basie, and from Thelonious Monk to Miles Davis. As a founder of the Newport Jazz Festival and countless other festivals around the world, Wein has brought a broad spectrum of musical artists to millions, forever changing the country’s cultural landscape.

Beginning in 1950 with the opening of Storyville in Boston, Wein presented jazz in a setting respectful of both the musicians and the audience. Since 1954, the Newport Jazz Festival has always reflected Wein’s vision and grit, attracting music immortals as well as aspiring young artists to his stage.*

Beginning in 1950 with the opening of Storyville in Boston, Wein presented jazz in a setting respectful of both the musicians and the audience. Since 1954, the Newport Jazz Festival has always reflected Wein’s vision and grit, attracting music immortals as well as aspiring young artists to his stage.*

Along with writer Nate Chinen, Wein has recently authored his memoir, Myself Among Others: A Life in Music. He joined Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita in a discussion on his life achievements, and on his unique perspective on the past, present and future of jazz.

.

.

____

.

.

“The week after our exhilarating Armstrong incident, Big Sid (Catlett) came through once again. Hoagy Carmichael, composer of “Stardust,” and so many other standards, was working at the Copley Plaza Hotel across the square from Storyville. The Plaza had the most elegant music room in the city, and was charging a six-dollar cover for its show — steep by 1950 standards. Sid knew Hoagy, and when he went over to the Plaza, he was able to lure the songwriter back to Storyville, where to everyone’s surprise and delight, Hoagy played and sang an entire forty-minute set. First Pops, and now Hoagy. Who, I wondered, would drop in next?”

-George Wein

.

____

.

JJM When was your career in show business born?

GW I guess I could say that it was born around the time I was seven or eight years old, when I used to sing on “kiddie” programs in New York. I wasn’t a professional, but every so often I would be part of a group of kids who were allowed to sing. At that same time, I played a classical piano recital. In junior high school I had a band that was paid two dollars or so for playing a dance. That was something…Then, on stage with Lionel Hampton at age sixteen, we played a tandem rendition of “Lady Be Good” on the piano, and that was it, because when I heard the applause, it reached me in a way I have never forgotten.

JJM Playing with Hampton at that stage of your life must have been a great thrill.

GW Yes, it sure was.

JJM What was your most memorable experience as a musician?

GW The most memorable experience as a musician in all my life was when I played in the Dominican Republic city of Santo Domingo with my band that included Warren Vache and Lew Tabacken. I believe we were a quintet or sextet at the time, playing in back of merengue and salsa bands consisting of something like four trumpets, four trombones and five saxophones. There were three thousand people in the stands, which was a beautiful recreation of a Greek amphitheater. We started to play the blues and I asked the drummer and bass player to lay out while I played solo blues, and within about twenty seconds, I had the entire audience clapping on the beat of four. I had a three thousand person rhythm section that picked up the inflections of my beat. It was one of the most thrilling things I have ever experienced, because as they kept urging me on, I felt like I kept playing better and better. It was a thrill I will never forget.

JJM And you also played with Charlie Parker.

GW Yes, and I also played on a weekly basis with Lester Young, which was one of the great highlights of my life.

JJM What are your memories of 52nd Street?

GW My brother and I used to come down to New York from Boston when I was around fourteen. I wasn’t even old enough to drive at the time, so he did all the driving. The first thing we would do after getting off of the West Side Highway — even before checking into our hotel — was drive from one end of 52nd Street to the other, all the way up to 5th Avenue, just to see who was playing. We would see the names of the great players of the era on the marquees there — Art Tatum, Jonah Jones, Red Allen, J.C. Higginbotham, Ben Webster…It felt as if we were entering jazz heaven. At night we would go out to many of the clubs, where I would drink ginger ale all night. It was during this time that I cut my teeth and realized I eventually wanted to be part of the New York scene.

JJM Did you pattern your own club in Boston, Storyville, after any particular club on 52nd Street?

GW Not so much after any club on 52nd street, rather the downtown clubs, particularly Café Society and the Village Vanguard, because they had a broader appeal than only featuring jazz groups. As I began looking for entertainment attractions on a fifty-week basis, where each week I needed a new attraction, I felt it was important to feature artists who would appeal to a jazz audience but who were a little more sophisticated on a broader basis.

JJM The Café Society was a pretty sophisticated club that wasn’t afraid to showcase a political edge along with jazz, folk, comedy, gospel…

GW Yes, I learned a lot from the Café Society, and it exposed me to many types of music I would have otherwise taken a few years to get around to hearing.

JJM How did Sid Catlett figure into your early success?

GW Just knowing him was a thrill, because he was among the greatest drummers in jazz history. Catlett played drums in my first club, Storyville, when I opened it in 1950. During this time, he often played for the Louis Armstrong All Stars. One night, after I had been in business for only about three weeks, Armstrong and the All Stars were playing a concert at Symphony Hall, so I gave Sid the night off and hired another drummer. I told Sid to bring Louis to the club after the concert, and sure enough, one by one they all filed in, almost as if it were rehearsed. First Cozy Cole went on stage, then Barney Bigard, then Earl Hines, then Jack Teagarden, and the next thing you know, “Pops” walked into the room and went right up to the stage as if it had been planned, and sang “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South.” When I saw that excitement, I knew that this business is where I wanted to be the rest of my life, with the best entertainers.

JJM How old were you at this time, George?

GW At that time I was 24. I had been in the Army and when I got out, I started the night club.

JJM Prior to the Catlett performance, you had to have the desire and the impetus for even opening a club. The trumpeter Frankie Newton played a role in that, didn’t he?

GW Frankie Newton played around Boston a lot and I became very friendly with him. He was my mentor, in a sense. My first venture involved making an arrangement with a hotel to play in a little room which we called “Le Jazz Douxce”, which is what we thought was French for “The Quiet Jazz.” Frankie and I played with just a bass player. Frankie taught me more than music. He was the first militant African American I had ever encountered. I will never forget one time we were walking along the street and he wanted a drink. I pointed out a bar to him, but he didn’t want to go in. I said, “Come on, Frankie, let’s go in. Nobody will bother us.” He said, “George, you have never been black one day in your life.” I have been thinking about that statement for the rest of my life, and I have never been able to figure it out, except that I am so close to the problems, and have worked so long with them now, that you begin to understand it. But when somebody says you have never been black one day in your life, it says something to you in terms of how difficult it must be.

JJM The way Newton played trumpet gave you the idea of having a quiet room for him to play in?

GW He played a lot with a mute, and he got the most beautiful sound out of it. Sometimes in clubs he would leave the stage and walk out and play among the audience seated at their tables. It was beautiful to see. Frankie had exquisite taste. He was the one who introduced me to people like Vic Dickenson, who became my favorite trombone player, and to Bud Freeman’s tenor saxophone playing when most everyone else was listening to Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young. While Frankie loved them, he got me to listen to Freeman also. I learned a lot from him. My friendship with him was a very important part of my musical development.

JJM What was your first disillusionment with jazz musicians?

GW This is sort of a sad story to me. I was partners with clarinetist Edmond Hall, and the two of us produced our first concert in 1949, “Edmond Hall and George Wein Present: From Brass Bands to Bebop” at Jordan Hall, which was a thousand seat auditorium where the New England Conservatory played. After the concert Edmond’s wife Winnie said that while we were partners, since Edmond was the “name” attraction, they should get 60% and I should get 40%. Being only 23 at the time, I just could not handle this emotionally. The concert was my idea, and I had done much of the organizational work, so I just could not accept that arrangement. It would have been very easy to accept it because I was playing with Edmond, whom I loved dearly. But it did open my eyes to the realization that it’s important to always know who you are doing business with. You may have love and respect for someone who may not have the same feelings for you in return. Although I had a wonderful relationship with them after this happened, it was a very disturbing thing for me at the time. I didn’t know how to handle it, so I resigned from Edmond’s group, which really hurt me. To me, my word is my bond. I have always been that way. If I give you my word, that’s it, and at the time I couldn’t understand how somebody would change an agreed upon deal.

JJM When was the first time that you gained the trust of a major artist?

GW People like Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis and Duke Ellington were easy to work with in one respect, but were not always flexible until you gained their trust. In the case of Monk, during his first tour of Europe, I was really taking care of him, doing things like driving him around town and taking him to restaurants. While our friendship was developing, I still had not gained his trust. One night in Manchester, England, Thelonious was in his dressing room in the company of some friends. As the time came for him to perform, I went to the dressing room to tell him. There was a six or seven step stage, and I ran up and down those stairs many times in an attempt to get his attention. But he wouldn’t move. He was too busy enjoying himself talking. Finally, I told him to get the hell on the stage. He looked at me, went up on stage, and proceeded to play a set that featured the drummer for 45 minutes. He came off the stage and I asked him why he performed such a set. He replied, “You ought not to have yelled at me.” I told him that I ran up and down these stairs many times to get him on stage, and I am getting too old to do that. Thelonious said to me, “If you ran up and down those stairs seven times, I don’t blame you for yelling at me!” From that experience, I gained his trust. Ellington was a little different. I would say I gained his trust at Newport in 1956, when we had a little success there.

JJM What inspired you to start the Newport Jazz Festival?

GW That originated when Louis and Elaine Lorillard came to my club in Boston in 1953. Elaine came in first, and I was introduced to her by Boston University English Professor Donald Born. We sat and talked about the exclusive resort of Newport — where the Lorrilard’s lived — as a great summer place but there wasn’t much to do there in the way of entertainment. It had the potential for being a beautiful outdoor setting for jazz, and we thought that perhaps we could do something with jazz there. Since there were classical music festivals — particularly in New England at Tanglewood — I felt we could do a festival of jazz music. Louis gave me a $20,000 line of credit at the bank to operate with. They went off to Europe for a vacation, and when they came back, we had the festival. Our first year featured artists like Dizzy Gillespie, Eddie Condon, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Gerry Mulligan, and Oscar Peterson. We never dug into the line of credit., and broke even our first year.

JJM Did the financial obligations of putting on Newport surprise you?

GW Well, I learned a lot, and later on when I came back on my own, I had to stand the burden of the financial responsibilities without any help. But I learned the business to the point that I could manage it within my own meager finances, and where it could break even and once in a while even make a little money. Although it never made a lot of money, the Newport Festival did finish in the black many times.

JJM The performance that most people think about when Newport is mentioned is Ellington’s in 1956. What are your memories of that particular performance?

GW I have so many memories of that, many of which are in the book. Two nights before his performance, I was at a party at the Lorillard’s house when he called me on the telephone. I asked what he was planning to play and he said he didn’t have a special plan, that maybe he would just do a medley. I told him that he had better come in here swinging, because here I was, working my fingers to the bone to accentuate the genius that is Ellington, and I am not getting any cooperation from you! We were quite friendly by that time so I could talk to him that way.

So, he picked out “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue.” I was standing to the side of the stage along with some of the other musicians, and Ellington began the performance with three piano choruses. Then, saxophonist Paul Gonsalves began playing, and once Duke saw the excitement that was building in the audience, he kept Gonsalves blowing. I was concerned about the crowd, and so were the security people. Many of the people were standing on chairs, dancing in the aisles, and pressing toward the stage. When the song was over, the cheering was like nothing I had ever heard before. A great memory I have of that evening is of Ellington getting the crowd “up,” and then bringing it “down” by playing the blues and a ballad. The tension in the crowd just dissolved. That is the most important thing I remember from that evening, the way Duke handled that crowd.

JJM Did you have any concerns that the crowd would get out of control?

GW The event was a “happening.” People left their chairs and were standing and dancing, but there was never any indication of anything getting out of control. My biggest concern was that I didn’t want them to rush the stage. I thought they might but they never really did. Years later, in 1969, Sly and the Family Stone performed at Newport, and the crowd rushed the stage because they wanted to get closer to Sly. The young kids climbed up on to it, and all the while Sly kept urging them on with “Higher, Higher, Higher.”

JJM You had some financial success promoting rock, but you chose to stay away from it.

GW I weakened when I read the underground press promoting various rock artists as great musicians. I asked a friend of mine, Joe Boyd, about who the best musicians were and he recommended Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull, who was a great flute player, and couple of others like drummer Ginger Baker. So I brought quite a few rock groups to Newport in 1969. While I got big audiences — more than I had ever seen — I had no control over the event. The musicians were okay musically, and they were able to do their thing, but it wasn’t a festival where I could create things. I decided that this was not the life I wanted. The fact that I could make more money was not important to me. The important thing to me was that I enjoyed producing festivals.

JJM Following his 1966 performance with Thelonious Monk, you quote John Coltrane telling you, “Sometimes I don’t know exactly what to do — whether I should play in my older style or do what I’m doing now. But, for the moment, I have to continue in this direction.” This was shortly after the release of A Love Supreme, when Coltrane moved into a more modal style of playing, and inspiring others to as well. What types of challenges did the music of Coltrane and other musicians he inspired pose for you as a promoter?

GW Some people think that John Coltrane was the beginning of the end of jazz. Others think he was the beginning of the beginning of jazz as we know it today. But there is no question that John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman are the two most important figures from the twentieth century with young musicians in schools now. They don’t study Charlie Parker or Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington. They are referred to, but when they play, they play like Coltrane or Coleman. They like the freedom of not having to learn too many songs.

JJM Yes, but did this playing present challenges for you as a promoter? Let’s face it, this type of music had a tendency to clear the house. One could say that Ellington was an audience builder, whereas Coltrane and Coleman were not the sorts of musicians you can build a huge audience around. Did that create a difficult challenge for you?

GW What it did is that it got us to move into promoting jazz crossover groups like Spyro Gyra. Weather Report was the first of those groups reaching young people, and of course Miles Davis played electronically. So, the musicians reacted in their own ways. They could play modal music within the structure of the electronic atmosphere, and the result was that they were successful in attracting a younger audience.

JJM The death of Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Johnny Hodges and Ellington caused you to consider the state of jazz. In your book you write, “The masters of jazz would all pass on but why should their music die with them?” As a result of this concern you formed the New York Jazz Repertory Company, which in its day probably faced the same sorts of questions regarding the jazz idiom that Jazz at Lincoln Center currently does. Is that accurate?

GW Absolutely. What we did with the Jazz Repertory Company was a preview of what they are doing at Jazz at Lincoln Center today. Jazz is like any art form. Whether you are a Renaissance painter like Botticelli or someone like Jackson Pollock who drips paint, it is all art. Jazz, in a sense, is the same thing. It is all jazz. There are traditionalists that play within certain structures and others who don’t. As promoters and as audiences who love jazz, we should develop a sense of taste in our ears to appreciate all of jazz. I know I do. I can listen to Ornette Coleman. I heard him in New Orleans a few weeks ago, and he was playing fantastically. There are so many young people out there now who play all kinds of new and different things, and I enjoy listening to them. I also enjoy hearing younger musicians who have really devoted their lives to the music of others. This diversity is what I feel jazz is all about. I always have and always will.

JJM As we conduct this interview, there is controversy concerning where players like trumpeter Dave Douglas are taking jazz…

GW To me, Dave Douglas is a wonderful musician. What he plays is jazz. Eventually, Lincoln Center must get around to recognizing all the energy that these younger players have — and Dave is not that young, he has been around quite a few years — but he has been developing and experimenting with many things. Lincoln Center does have that responsibility to, one, preserve the traditions of the music and, two, encourage explorations in the music. They haven’t had the time or the finances it takes to encourage explorations to any great degree. Eventually, they will do that. They will have to do that.

JJM It must be interesting to view their work from your perspective, given all your experience promoting concerts and your work with the New York Jazz Repertory Company.

GW I wish I had the money when we had the New York Jazz Repertory Company that Jazz at Lincoln Center has to do its programming with. But, we did the best we could given our resources, and we made our mark. I have had great experiences in so many different directions. We were adventurous as producers. We came in with ideas, tributes, and different combinations of musicians that hadn’t been done before. The very first concert we did at Newport featured Eddie Condon and Lennie Tristano on the same show. Nothing like that had ever happened before. Now I see these things happening all the time, and I realize that we were the pioneers in many of these things, particularly in the way jazz repertory is presented. Nobody is a genius. Every idea you have comes from somewhere. All my ideas were related to something I saw either in classical music or in literature or anything creative — you pick up things. Festivals come from the medieval times, when there were jousts and fights and crafts and food and everything else. So, when you look at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, it could be a medieval fair.

JJM What you did with Newport and New Orleans is create cultural events, rather than a concert event like Woodstock.

GW Commercialism is fine, you must draw an audience. A festival without people is not a festival. But you better have credibility artistically with what you include alongside your commercialism. We brought in groups who we knew would draw people, but also did not ignore the little jazz guy who played from his heart and who was going to play that way no matter how much money he did or didn’t make at any given time.

There is a difference in the word “culture” today because we have added a three letter word to it called “pop culture.” The differentiation between “pop culture” and “culture” is very strong, and you have to study it. Everything is culture. The food we eat is culture, and the clothes we wear is culture, but it is not the same as the great violinist, the great writer or the great philosopher who can change the civilization in which we live. These things are culture on a higher level and you can’t put the word “pop” in front of them. I never put the word “pop” in front of “jazz” as culture. That is the difference between Woodstock and, say, New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, which includes some “pop culture,” but basically is a true expression of the musical and cultural background of Louisiana, and what eventually became America, in general.

JJM In response to your fears you shared about your future, Thelonious Monk’s saxophonist Charlie Rouse once said, “George, I am not worried about you. You are a good hustler.” Did you ever think that you were on the wrong path at any time?

GW I guess I felt I was after the second disturbance at Newport in 1972, before I took the Festival to New York. I was a little discouraged I think for a few minutes there. But for some reason, my mind always kept working and rarely became discouraged. I never lost hope in my life. I always felt that I would make it, that whatever I was doing was important and I would continue to be successful doing it. It wasn’t that I felt I was such a genius or so brilliant, but when I go to bed at night I often can’t sleep because I am always thinking of things to do next. I have the fiftieth anniversary of Newport coming up next year, and I can’t stop thinking about it.

.

.

___

.

.

Myself Among Others:

A Life in Music

by

George Wein

.

.

*

.

.

About George Wein

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

GW Boy. That depends on which childhood. My first, second or third?

JJM I assume you are in your third now…

GW Yes, that’s right. Ted Williams was one, but before him, I used to root for Joe Louis. Many of my real heroes as a child were radio stars like Eddie Cantor, Bing Crosby, and Al Jolson. I cut my teeth on their music at a very young age. Then, I got involved with jazz, and loved the bands of Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmie Lunceford and Duke Ellington. When I discovered Louis Armstrong, he changed my life.

JJM If you could have attended one event in jazz history, what would it have been?

GW That is quite a question. Some of them I may have created! I wish I was in Chicago when Louis Armstrong recorded the Hot Fives and Hot Sevens and nobody had ever heard anything like that before. That might have been incredible, because that is still some of the greatest music ever played. That was the beginning of great solo playing in jazz. Before that it was ensembles with no great soloists. Louis emerged at that time and changed everything. Everything that has happened since goes right back to Louis Armstrong, so, I would have liked that.

.

*

.

George Wein is the founder and chief executive officer of Festival Productions, which is the premier producer of music events around the world each year. He has received France’s Legion d’Honneur and countless other awards. He lives in Manhattan.

.

.

______

.

.

Interview took place on June 18, 2003

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with jazz critic Gene Lees.

.

.

* Text from the publisher

.

.

.