_____

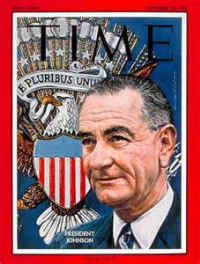

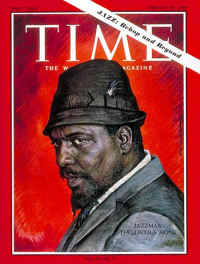

50 years ago this week, Time magazine – at the time a critical weekly linking Americans to news and features of the world – had planned to run a cover story on jazz music, with the cover devoted to pianist Thelonious Monk. Instead, the events in Dallas on November 22 caused Time to shelve the story until February 28, 1964, and they ran a cover of Lyndon Johnson on November 29, 1963 instead. Reportedly, this decision, according to Monk biographer Robin D.G. Kelley, caused Time to destroy “the three million copies they had already printed bearing [Boris] Chaliapin’s portrait of Monk.”

This discussion about the Time article appears in our December, 2009 interview with Kelley:

JJM Of journalist Barry Farrell’s Timemagazine’s article on Monk and its impact on jazz, you wrote, “While praising Farrell for writing an accurate, well rounded portrait, in depth of a complex personality, [prominent jazz writer] Leonard Feather nevertheless concluded the essay might actually harm jazz and race relations.” We know that Leonard Feather had an issue with Monk, but why did he feel that this article could harm jazz and race relations?

RK There are two reasons. Leonard Feather sort of took the bait about Monk’s character and felt he was not the best role model for jazz. He felt there were all these other role models that Farrell should have written about, like Oscar Peterson, like Dizzy Gillespie, and others who were in fact not doing drugs or drinking, who didn’t wear funny hats, and who didn’t engage in strange behavior. So he was basically saying that jazz needed a more respectable musician on the cover of Time magazine, not a crazy one like Monk. But, as far as Feather was concerned, that is what Time was interested in. The other reason too is that since Time reached a non-jazz and predominantly white audience, having the image of Monk on the cover would reinforce the stereotypes whites had for black jazz musicians. But what Feather doesn’t do is question the authenticity of Farrell’s piece which Ralph Gleason, the jazz critic in San Francisco, does. Gleason was saying that the article wasn’t even correct, and went after Farrell in a way no other critic did.

JJM And the piece was written at an interesting time, on the cusp of the civil rights movement, originally scheduled to be published the week of Kennedy’s assassination. It got moved back to the spring of 1964

RK That’s right, and Barry Farrell himself was fascinated with the question of race in music because I believe he wrote an unsigned piece as the music critic for Time called “Crow Jim and Jazz,” which discussed how, in his opinion, white jazz musicians were struggling to get work, and described the black jazz musicians he identified as angry and revolutionary, and whose radical music had no place in jazz. The fact is that Monk’s Time profile emerged at a really hot moment when, on one side was the jazz avant-garde, which fairly or un-fairly was being identified with black nationalism and radicalism, and on the other side were the older swing musicians who were seen as conservative. These characterizations were not necessarily accurate but what they did is embody a political debate that was going on in the nation at the time and Monk sort of gets caught in the middle. It is so ironic that a right-wing, conservative publication like National Review claimed Monk as their man because he knew how to swing, at the same time that a left-wing publication out of Harlem like Liberator claimed him as their guy, describing him as a revolutionary being exploited by the Baroness. So, it is fascinating how Monk became a symbol that people could write their own political agenda around.

JJM And before that he was a symbol to the artistic community as well. The beat artists, for example, really dug Monk. You wrote, “They found in Monk’s angular sounds and startling sense of freedom a musical parallel or complement to their own experiments on canvas and in verse.” So, he had this history of being a symbol of several different movements.

RK Absolutely, and, in fact, I would argue that the beat generation’s writers, poets and painters helped put Monk on the map.

_____

Click here to read the entire interview

Monk in 1963, playing “Off Minor”