.

.

…..Phil Woods was one of a kind. He had a big sound, and a personality to match it. The alto saxophonist and clarinetist, who died in 2015, had a long, remarkable jazz career, stretching from his teens to his final days just short of 84. He was a leader on well over a hundred records and a sideman on hundreds more. His blistering intensity, creative musical logic and versatility were sought after for their ensembles by the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Quincy Jones, and he led his own quartets and quintets for decades as well. In his unique, immediately-identifiable sound, you can hear Charlie Parker, one of his main idols, and Johnny Hodges, another primary influence, along with Lester Young, and Benny Carter.

….. Over the years Woods collected bits of his own writing: musings and stories from his life on the road and his evolution from a teen newly turned on to jazz in Springfield, Massachusetts, to studying with Lennie Tristano in New York, attending Juilliard, and not long after becoming a full-fledged jazz musician. The resulting book, Life in E Flat (Cymbal Press), tells that story, and along the way provides a rich sense of Phil Woods the man. We have the noted jazz writer Ted Panken to thank for this final product: Woods asked Panken to edit his rough “manuscript” and Panken obliged and included important new additional Woods interview material, as well as brought a great deal of overall cohesion to the work. The result is a highly entertaining, full-throated jazz autobiography that gives a vivid sense of the artist as a human being, warts and all. The writer Henry Miller once wrote that, “The aim of life is to live. And to live means to be aware: drunkenly, serenely, divinely aware.” Judging from the tale of Phil Woods’ life, that is an approach to living that he heartily endorsed.

…..In December, 2020, Ted Panken and pianist Bill Charlap, who played with Woods’ quintet for many years, participated in a conversation with Bob Hecht, for Jerry Jazz Musician. That conversation follows, edited slightly for length and clarity.

.

At the conclusion of the interview the reader will find a Spotify playlist featuring many of Phil Woods’ most important, memorable, and enjoyable recordings

.

.

photo by Carol Friedman

.

___

.

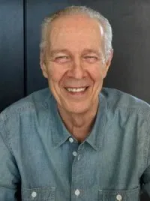

Ted Panken is a jazz journalist who has written for DownBeat, Jazziz and Jazz Times, and has penned over 500 jazz album liner notes. In 2006 he was the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award in Jazz Journalism by the Jazz Journalists Association.

.

___

.

Bob Hecht frequently contributes his essays and personal stories to Jerry Jazz Musician. He has a long history of producing and hosting jazz radio programs; his former podcast series, The Joys of Jazz, was the 2019 Silver Medal winner in the New York Festivals Radio Awards.

.

.

___

.

.

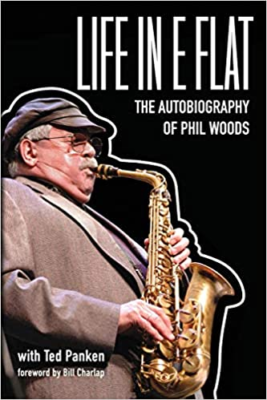

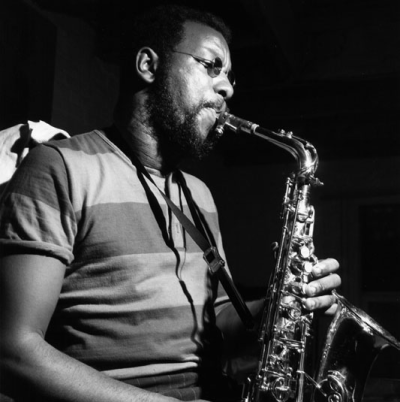

photo by Brian McMillen

Phil Woods at Keystone Korner, San Francisco

August, 1980

.

.

“From his earliest recordings, [Phil] Woods’ improvising had an organic flow, a highly nuanced tonal palate, a visceral quality, and an articulate, original, imaginative continuity. Along with all of these natural gifts was [his] tireless work ethic. He never lost his lust for music. He demanded the respect of his fellow musicians by modeling the highest standard of excellence, always.”

-Bill Charlap

.

.

Listen to Phil Woods play “Come Rain or Come Shine,” from the 2006 album American Songbook II, with Bill Charlap (piano), Brian Lynch (trumpet), Steve Gilmore (bass) and Bill Goodwin (drums)

.

JJM On his horns, Phil Woods obviously had a voice all his own; and so he does in this book, Life in E Flat. As you say in your foreword Bill, reading this book is “like having a long conversation with the man…” I never knew Phil Woods personally but reading this I feel as if I do know him to an extent, and what a unique and compelling character.

BC Well, he was definitely all of those things, and I think we very much have to thank Ted for the incredible work that he did putting all of this together in a narrative that really makes sense from start to finish. So, thanks Ted.

TP My pleasure. Thank you, too, Bill—I think you even did some interventions for me at a particular moment…

BC Well, listen, I helped wherever necessary, of course, but I wrote just a paragraph, you put it all together.

JJM Ted, you first did a DownBeat cover profile on Phil, back in 2007. Was that experience instrumental in your becoming the editor of this book?

TP Yes, it was, and I describe this in my introduction, the “Final Chorus” piece in the book, that precedes Phil’s manuscript. I had had a somewhat checkered personal history with Phil. There was one instance during the 80’s when I had done a lot of research on the history of jazz on the South Side of Chicago, and I wanted to talk to [tenor saxophonist] Budd Johnson. He was playing at a Greenwich Village jazz club called Sweet Basil, which was on my route home to Bleecker Street as I was walking from the Village Vanguard. And as I passed by Sweet Basil that night, where Budd was performing, I saw him in the window. He was sitting with a middle-aged white guy with a mustache and a cap and a leather jacket. I’d probably had maybe a drink too many and I went in to try to approach Budd Johnson because I very much wanted to talk with him about Chicago in the 1930’s and the Earl Hines band, and such things. But before I could do that, the gentleman he was with took umbrage, and made his displeasure felt very clearly and more or less told me he’d take matters into his own hands if I didn’t leave right then and there, which I did. And that was Phil.

I had admired Phil’s musicianship; I must say at that time I wasn’t so much of a fan although I really admired him, but then I hated him! (Laughter) And then a number of years later, maybe around 2004, DownBeat asked me to include Phil in a piece in which instrumentalists were asked to talk about one favorite person on their instrument. Charles McPherson had chosen Bird, so I called Phil, thinking he might talk about Benny Carter, whom I knew he loved. But Phil decided that he wanted to talk about Harvey LaRose, about whom he writes very descriptively in Chapter 2.

JJM His early teacher…

TP Yes, his early teacher who gave him an exhaustive, probably jazz conservatory level education when he was in his early teens. I said, well that’s fine, but I have a feeling DownBeat may not accept this. And sure enough, DownBeat didn’t. And I was tasked with giving Phil this news. So I did, and Phil soon thereafter went on his social media to his email list, and denounced me and DownBeat to the entire list. And this is where I think Bill and [trumpeter] Brian Lynch did a bit of an intervention, and told Phil that I was okay. Phil then retracted his denouncement as far as I was concerned, and then DownBeat’s publisher then did some diplomacy and all was then peaches and cream. So that’s the context to my doing that DownBeat cover story in 2007.

After we finished our interview, when I saw Phil on his oxygenator for the first time and understood the actual magnitude of his emphysema illness and what he was dealing with just to play and perform, I told him what had happened, that story about our checkered personal history. He just cracked up, he thought it was hilarious. He apologized and a year or two later when his band was at Birdland, Phil approached me and asked me if I’d work with him on the book. I stated a price and Phil agreed to the price. And after I read the manuscript that he had, I told him that I would only do it if he would do a number of interviews with me to fill in gaps on other subjects, which he did. I interpolated that material into the manuscript which he presented, and I kept editing and editing and editing, before his death and after his death, and finally arrived at what people can now read.

JJM What kind of shape was the manuscript in when he first handed it to you?

TP Let me ask, Bill, did you read the manuscript in early form?

BC I did…

TP I’m curious what you think of my impression of it…it was very well-written in parts, it was very discursive, it sounded and read like the way he talked. There was no problem weaving the additional interview material into the text, it was very seamless…and it was way too sloppy and didn’t always come off so well on the printed page.

BC I think you just said it. It was exactly that, it was a collection of articles—it was like a bunch of really terrific songs that didn’t read as a symphony. And as I said before, we have Ted to thank for this now being a narrative from start to finish. And Ted’s prologue sets things up in a very beautiful way and it’s not in Phil’s voice, so Phil’s voice speaks out that much louder when the reader gets to the first chapter. Also, Brian Lynch wrote something beautiful at the end, called “Why Phil Woods Matters” and Brian is wonderful at expressing himself personally and deeply; so those two bookends are really key, I think, for the reader.

JJM Ted, I know you did seven additional interviews with Phil: over what time span were they?

TP About six months, during 2009-2010.

JJM So you and Phil must have gotten to know one another pretty well during the course of that—did you hit it off?

TP Well, Phil was very professional. I’d say we developed a warm professional relationship. I was only at Phil’s house once; the interviews for the book were all over the phone. I was at his house when I was covering him for that 2007 DownBeat piece, which coincided with the recording of the second volume of American Song. So he invited me to that and put me up at the Deer Head Inn and we went to the recording studio which was nearby. Bill was there. So that was my only personal interaction with him apart from the interview for that article in the hotel room. You know, as a writer you develop different levels of relationships with the people you are writing about; and some are friends, on different levels of friendship, and with some you have, hopefully, warm professional relationships. That’s more or less what it was with Phil, and I think I wanted to keep a certain distance so that I could have more editorial independence in the rather intuitive process of creating as tight a narrative as possible.

JJM Bill, I remember your telling me the story of your first experience of playing with Phil, and basically having to hang on for dear life…

Bill Charlap

BC Well, I was on one of those jazz cruises, and this one was very saxophone-oriented, a tribute to Benny Carter. So there were Lou Donaldson and Phil Woods, and David “Fathead” Newman, Flip Phillips, maybe Houston Person…and young Jon Gordon, who’s my dear friend and a protégé of Phil’s. We were all in different bands, I was in Jon’s band; and one day we were playing in a bar on the ship and Phil came by and said, “Can I play a couple of tunes with you?” And of course…

TP “No Phil, you can’t!” [Laughter]

BC Hell yeah! Of course, such an honor…so I remember he took out his horn and he said [Bill mimics Phil’s fast-talking, take-care-of-business attitude]: “You cats know ‘Slow Boat to China’”? And I said, “Well, gee, I’m not really too sure about that…” And he says, “Well, it’s too late now!” And he just starts. [Bill sings the first line of the tune, very fast]. As I said in the book, playing with him is like grabbing the caboose of a bullet train going two hundred miles an hour. It really was like that. It’s sink or swim. He really wanted to get right to it. He was impatient. Part of that was his intensity, part of it was his focus, part of it was also a badge of honor, and with him you realize that you have to step up to the plate and you don’t “phone it in” at any time.

That was the thing about playing with him, no matter if there was one person in the audience or three thousand people in the audience—if no one was in the club he was playing at full throttle and if it was full he was playing at full throttle. He was just always movin’ fast. And I don’t know if he understood that other people didn’t conjugate as fast as he did. That was part of his genius. It was really this Olympic-level of intensity.

The same kind of thing happened a few months later with Phil: I didn’t realize it but I was kind of getting auditioned for his band. I was playing a duets gig with [bassist] Steve Gilmore at the Deer Head, and Phil came in to sit in. Afterwards, as was typical with Phil, everything was very intense and moving very quickly. I was living on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and he calls me up and says, [and here Bill again mimics Phil’s rapid-fire, acerbic way of talking] “Hey baby, it’s Phil Woods, and I’m just sniffin’ around, we have a tour coming up in Germany and just wanna know if you can sit in for Jim McNeely; it’s a month-long tour and we leave in a couple of weeks.” So I told him by hook or by crook I’d be there. He says, “Well, I’m just sniffin’ around, thanks baby. Bye.” And about two minutes later the phone rings, it’s Phil again, and he says. “Okay baby, the tour’s on, and you know, actually, we want you to join the band.”

It went like that, and my head hit the ceiling because I was going to hear Phil Woods with Jon Gordon when we were in high school—this was an iconic figure from my youth. And I was kind of terrified, but also incredibly excited and couldn’t believe that opportunity was coming my way.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to Bill Charlap play “Somebody Loves Me” from his 2005 album Bill Charlap Plays George Gershwin. The track features Phil Woods on alto, as well as Frank Wess (tenor sax), Nicholas Payton (trumpet), Slide Hampton (trombone), Peter Washington (bass) and Kenny Washington (drums).

.

JJM I love the comment you mention in the book about what [guitarist] Bucky Pizzarelli said to you about getting to join Phil’s band.

BC It was wonderful. I said, Bucky. I’m going to join Phil Woods’ band, and Bucky says [Bill mimics Bucky’s distinctive accent], “Ahh…You’re gonna get your doctorate!” And I understood it to mean, correctly, “You’re gonna get challenged and schooled by a master.” And there’s some good stuff in Ted’s prologue about my experience of being schooled, old-school, by Phil, on that first tour with him. His book of tunes was rather vast, and you never knew what he was going to pull, so there was no way to be totally prepared.

The first night of the tour we played Ronnie Scott’s [in London] and the second night was somewhere in Germany, a big concert hall, and Phil calls “Pete’s Feet,” a great Jim McNeely tune written for his son Pete, a typical McNeely composition, with all these different sections and all these rhythmic hits, and it’s just freakin’ hard to play and hard to even negotiate the improvising sections, and I cut the hog so badly. I guess I played okay on the blowing sections but I just played the chart terribly. But Phil didn’t say anything. Next morning, German breakfast. Everyone’s eatin’ meat and cheese. I walk in with my head kinda down, my tail between my legs, feeling awful about my playing on “Pete’s Feet” the night before. Phil sits there, real quiet, just chewing, you can hear him chewing, it’s so quiet at the table. Then Phil says, “Hey, why don’t you sit down, youngster!” And I’m thinking, oh no, what’s coming. Phil says, “So, you sleep well last night?” And here, real quick, Phil reaches across the table with both his hands, one in front of the other, and puts them directly in front of my face, and holds them up at right angles, and says, “Did you have dreams of little FEET?” [Laughter] And that’s him. He was serious, like ‘You messed up so badly on that thing.” But he was also telling me he had humor about it, he understood what had happened. And I laughed. That’s all. It loosened it up.

JJM Ted, in the book Phil talks about coming of musical age in Springfield, Massachusetts, and being strongly attracted to a Black club there, Phono Village, and becoming enamored of the whole Black experience and recognizing that jazz is essentially a Black invention. And he stated in your 2007 interview that he “had the self-doubts of a white guy coming up.” I read an interview with another great alto genius, Lee Konitz, who said he felt like he spent a lifetime feeling apologetic for being white. And I wonder if you have any other thoughts about race and about Phil’s feelings about being a white jazz musician.

Phil Woods, 1983

TP Well, that’s a long and involved subject, Phil and race. That’s one of the things I wanted to talk with him about, one of the things I kind of insisted we discuss in our interviews. I’ll start with this: When I was thinking about the arc of Phil’s life, I was thinking of Norman Mailer’s long essay in the fifties, “The White Negro” and the obsession with Charlie Parker among the white poets and writers who formed, though I don’t like the word, the Beats, who were in cultural ascension at that time. That includes Kerouac and Ginsberg and Mailer and a cornucopia of iconic figures, who did not stick with jazz later on. I saw Phil in a sense, and forgive the expression, as the “wet dream” of those guys. This was a guy who addressed bebop and Black music on its own terms. He was the first call of Dizzy Gillespie and Quincy Jones and Thelonious Monk. He married Charlie Parker’s widow; he raised Charlie Parker’s son. He had to deal with these things in a very real and existential way that was no fantasy. And he also had to deal with a lot of brickbats thrown his way—Mingus famously might have confronted him one night.

Phil had been through the wars, including on that 1956 Birdland All-Stars tour he describes so vividly in the book. [A tour that contained some racial lessons.] But, on the other hand, once Phil started forming his bands, they were almost exclusively white bands. I asked him about that, and he said, well, Bill Goodwin is his brother-in-law and he and Steve Gilmore both live in the Poconos, near where Phil lived, and there weren’t a lot of Black musicians in the Poconos. He said he wanted to go, as he put it, “salt-and-pepper” but he couldn’t and he wasn’t going to go out of his way to do it and was very happy with his band, “thank you very much!”

Phil’s models were Black: he loved Benny Carter, he loved Johnny Hodges, he idolized Bird. He describes that while attending Juilliard he would jam at the Paradise Ballroom, with “Big Nick” Nicholas, he played with Charlie Barnet’s band, he played the Apollo. There used to be a phrase in the late fifties and early sixties, “Crow Jim,” which was a term for so-called reverse racism—and I say so-called—of the contributions of white musicians being diminished somewhat in a purely racialized sense. And I think Phil certainly felt that he had been targeted for that, and I think that stuck with him. I don’t know more about this than what he gave me in his text but I feel that Phil didn’t have any reason to feel in any way insecure or inadequate about his musical production in the context of his role models.

JJM Bill, do you have any thoughts on the subject?

BC Well, you’re opening up a very big door, but there have always been more important contributions from Black musicians in jazz, and that’s simply like saying sonata-allegro form was written better in Germany in the seventeen-and-eighteen hundreds than it was written here. Of course that’s true.

There’s nothing wrong with pride of race; there’s nothing wrong with respecting the genesis of the music. But we also have to respect each other. Anyway, I’ve never, ever felt any racism from Black musicians. Ever. Ever.

Isn’t jazz about being yourself? And isn’t it a beautiful thing that Paul Desmond played the way he played? I don’t think he was trying to be Black or white. He was just being Paul Desmond. And do I think that he played the blues with the depth of Cannonball Adderley? No, probably not. I read that Lee Konitz felt conflicted about playing the blues, because he felt it wasn’t “his music.” But I would ask, “Why isn’t it his music?”

There’s so much here in what you’re talking about; but ultimately, is Phil Woods valid? Of course he’s valid! He was hired by Thelonious Monk and Quincy Jones and Dizzy Gillespie and Oliver Nelson because he was a great, great, great musician. And they were great, great, great musicians, and human beings. And I really like the piece in the book where Phil talks about how he was feeling insecure about these things and Art Blakey and Dizzy Gillespie sat him down and said, “You can’t steal a gift.” So it is a gift, from African-Americans, it is a gift. I don’t think that you would have Bix Beiderbecke without Louis Armstrong; but then again maybe you wouldn’t quite have Lester Young without Bix Beiderbecke.

TP Or Frankie Trumbauer…

BC Especially Frankie Trumbauer. America is not a racially equal country. America has the most profound character defect, and it keeps happening, and people are saying why aren’t we talking about this, first and foremost, because it is the central-most important issue of our country.

JJM Another sometimes thorny issue is addressed in the book, and that is the question of whether someone is an innovator or not, and what is the importance of that. Phil stated clearly he felt he was not an innovator.

TP Well, Phil makes a statement, about why he was a first-call studio musician, and why he was making a good living for about ten years in the studios; he says he could read anything—he could read “fly shit” as he puts it—he was able to read whatever charts they put in front of him, but was also able to bring a modern jazz interpretation when needed. He had a good grounding in modern classical music as well, so he could bring all these areas of knowledge as needed. Phil certainly had his own sound, but his style was more of a blend and he wasn’t really interested in creating a new stylistic path, and he didn’t go in that direction. And he says so quite frankly in the book.

BC Well, you can be an influential individual without necessarily being an innovator. You can certainly say that McCoy Tyner is an innovator. And you can certainly say that Charlie Parker is an innovator. Louis Armstrong is an innovator. Art Tatum. Bud Powell. John Coltrane. All innovators. Why? It’s almost like there’s a door to the big room, and there’s no way to get in that room anymore, so they crashed down the wall around that door and now you can’t get in there without bucking through that crashed-down wall, without dealing with their innovations. But then again, maybe I wouldn’t put in that list of innovators Wynton Kelly, or Sonny Clark, or Red Garland. However, don’t you hear Wynton Kelly’s playing in Herbie Hancock? Don’t you hear Red Garland’s playing in Tommy Flanagan and Kenny Barron? They’re certainly influential. They may not have changed the face of the entire oeuvre, but to bring it back around to Phil, I would have to agree that he was probably not an innovator, but a hugely influential alto saxophonist who has influenced many who have come after him in their approach. So I don’t think he was any more an innovator than Cannonball Adderley was, but I don’t think anybody decides, “I’m going to be an innovator, I’m going to crash down those walls and change everything.” I think they’re just being themselves and as a by-product of being themselves, that’s what happens.

TP But while Phil may not have been an innovator, he was a unique figure.

BC No doubt.

TP There’s no one really like him: to be able to be a first-call studio, first lead alto player and a great soloist, that’s kind of a rare combo, as it is with first lead trumpets, and being able to perform both of those functions. It’s like with Phil there was no left-right brain separation in the way he was able to function musically.

BC That makes perfect sense. Some stars are planets, but I’d hate to look up in the sky and see only the planets.

JJM In your introduction, Ted, you write that Phil “…neither sugar-coats his foibles nor minimizes his strengths. He does himself full justice.” He didn’t get to see the book manuscript in final form, did he?

TP No, he didn’t. Phil wanted to keep some of his pet licks in there, like certain aphorisms, certain jokes, and I tried to remove those licks as much as possible. He was a pretty good writer but he wasn’t disciplined; he was a very disciplined musician but he wasn’t a very disciplined writer, but he was a very evocative writer. His stories were great, very vivid and descriptive, you kind of feel like you’re there. And he was very self-aware, at least in his authorial voice. He didn’t really spare himself. He’s very unsparing with himself when he writes about his experiences with drugs, in the eighties, with cocaine, and his drinking, which led him down some very dark paths and some tragic paths for him. He describes that, and he went there with me, in my interviews. I thought it was important for a complete portrait for people to have that. I think it illuminates our understanding of him. Some people might feel differently…

BC It’s definitely important, Ted, I’m glad that it’s there, and I think he would be, too.

JJM And he talks about all of that in not at all a maudlin or self-pitying way, just straight up.

TP Life for him was about squeezing all the juice out of the lemon, as he put it. It’s amazing, there are some people who when you know them a little bit, and they’ve lived into their late seventies or early eighties, it seems kind of remarkable that they made it that long just because they lived life with so much gusto. And Phil Woods had a full life and his mental capacity seemed to be undiminished all the way through, which is a wonderful thing.

JJM And it seems he was playing his ass off till near the end, too…

TP It seems so to me. The last time I saw him was in Detroit in 2015. He was playing open air, and gosh, I just enjoyed that set so much, it was such an “old master” set, what he and Brian Lynch were doing up there, with Bill Mays, Steve Gilmore and Bill Goodwin. What a sound.

Phil Woods, 1978

JJM Phil had emphysema for the last fifteen years of his life; he had been a heavy smoker. I heard him joke once that emphysema was “Nature’s way of telling him to play fewer notes.” [Laughter]

BC Well, I’ll tell you what—the last concert I played with Phil was a celebration of Charlie Parker, and it was my trio with Kenny [Washington] and Peter [Washington], and it was Phil, Charles McPherson, and Jesse Davis: a very nice assemblage. And Phil, at that point, was sitting down to play, and had the oxygen tank, and it was remarkable to hear those three players play, next to each other, playing such tunes as “Embraceable You” and “Confirmation,” because you really heard what was so special about all of them. And Phil, particularly, his sound was incredibly rich; and he was playing fewer choruses and fewer notes. It was really choice, yet he didn’t play with any less depth or intensity or value just because he was diminished. He figured out how to make whatever he had work for him, and it was an amazing thing.

TP He also just kept this huge sound—I remember hearing him at Birdland, sans microphones, and he was just filling the room. Pretty amazing.

JJM So much of his story in the book also reveals how physically and psychologically challenging and taxing “the road” is, the ordeal of all that traveling. I love his comment about that: “They pay us to get here, but the music is free.”

BC That was Phil’s way of thinking, for sure. He loved it though. He loved traveling—he just loved singing his song all over the place. He might have griped, and I know it got very, very difficult, of course, when he was dealing with the physical stuff, which I wasn’t really around for when it was getting that bad. So that, I trust, is entirely true, that it was too much. But, I also think that, with all the kvetching that went on, he loved it. I never saw him so happy as when he was on the bus, listening to Elis Regina, while we were driving from one city to another city, and perhaps he was a little high, and having a good time.

JJM And the man loved to laugh, didn’t he?

BC Oh, he was hilarious. In fact, I had a very difficult time keeping a straight face when I was around him, because I knew, like the rumblings of The Munsters dog, he was always ready to zap at me somewhere. He did this thing once, he said [mimics Phil’s voice] “I’m watchin’ you, baby, I’m watchin’ every move you make.” [Laughter] And literally, I think on that same first tour, we were on a plane and Phil was sitting on an aisle seat, and he’s sleeping—his cap is tucked down a little and he’s sleeping, but you could still see his eyes—I happened to be standing there, waiting for the bathroom, watching him sleep, and I don’t know how he knew this, but all of a sudden his left eye opens for a long moment and then it shuts again. [Laughter] In other words, “I’ve been watchin’ you.” But he didn’t change his facial expression, he had complete control like a great comic actor. It was hysterical. I have no idea how he saw I was up there.

JJM I’d like to just mention his clarinet playing, which is sometimes goes ignored in the face of his tremendous alto playing, but he was a wonderful clarinet player, with a beautiful sound—and his own sound—on that instrument as well.

BC You know what he called the clarinet? Typical Phil, again—“Ah, the Inflictor!” You know, because it is a hard instrument to control. But he was a beautiful clarinet player, with a rich, warm, kind of reedy, original kind of sound. [Clarinetist] Ken Peplowski talks about his clarinet playing, that’s saying something. We made that Astor & Elis record, which isn’t a quintet record, but was a record of music of Astor Piazzolla and songs that Elis Regina sang, and Phil plays gorgeous clarinet all through that record.

TP Wow, I don’t think I know that record.

BC Well that’s a great record, and I’m proud to be on it. Beautifully done, an arranged album of Phil’s and he plays alto on it too, but also a lot of clarinet.

.

A musical interlude…Listen to the 1981 recording of Phil Woods, Tommy Flanagan (piano) and Red Mitchell (bass) playing “Goodbye Mr. Evans”

.

JJM One of Phil’s most famous compositions is “Goodbye Mr. Evans,” in which he beautifully expresses his feelings for Bill Evans. Bill, I’m curious, did Phil ever talk with you about Evans?

BC Well, only in as much as how much he admired him. He loved Bill Evans’ music and his musicianship very much. But I do remember that he was very proud of that piece. And it is a very good piece of music, it’s so well-developed. That’s the type of writing that he was doing, which was more like Johnny Mandel and Michel Legrand than anything else. You know, it’s all developmental, in the way that Cole Porter was. [Bill sings] “Night and day, you are the one.” That’s the whole song. With Porter, it’s always some melodic cell thing, like Beethoven [sings the first eight notes of Beethoven’s “Fifth.”] That’s it. That’s the flash of genius, and all the rest is development, the best development. Well, with Phil and that piece, it’s [sings the first phrase] And that’s a very beautiful, lyrical phrase, right? Well, it’s Charlie Parker! [sings the same five-note phrase but much faster and with bebop phrasing] That he did tell me about that piece. You can hear Bird, and developed beautifully in perhaps the way Mandel or Legrand might develop it, particularly when you get to that middle section and you get to E major for a hot minute. Anyway, it’s a very good piece and he felt that it was an elegy for Bill of course, first, and it then became a bit of an elegy for all different fallen heroes that Phil had.

JJM As you express in the book, he played and lived by his own terms until the end—and died that way too.

TP I believe the phrase you used, Bill, was, “God’s will, Phil’s terms.”

BC That’s it, that was Phil, all the way.

TP That was great.

BC And I remember thinking that, the day he died—that’s him. This is how it’s gonna be.

JJM And Bill, you visited him at the end, right?

BC Yeah, I was on my way to William Paterson University, I think I was in my first year of teaching there, and I got a call from [Woods’ stepdaughter] Allisen saying Phil wants to see you. He’s going to go tomorrow. So I went right then, called the school and told them I couldn’t make it. And I sat with him in the hospital in East Stroudsburg for a long time. He was still being completely himself. I remember one person, I forget who it was (or maybe I don’t but I won’t say who it was) and this person made an analogy to something he was talking about, and he said, “It’s just like that!” And Phil sat there—he’s dying, he’s on his deathbed, man— and he goes, “No it’s not.” [Laughter] And he withered the poor guy. But it was so funny because it was true. The guy had said something corny and Phil just wasn’t gonna have it. All he wanted to do was listen to music, and he listened to things that he liked. It was touching being there.

JJM Do you recall what he was listening to?

BC Well, one of the things—and it meant a lot to me—was a record I had just done with Tony Bennett and with my trio, and also with Renee [pianist Renee Rosnes, Bill’s wife]. And he wanted to put that on, he really loved it. That was a very nice kiss goodbye for me. It meant a lot to me.

JJM And I love that his sardonic sense of humor was alive until the end. The phone conversation with Brian Lynch…

BC Man, I was there and I remember it so well. I’m setting with Phil at his bed when Brian called. Phil had tears in his eyes while Brian was telling him how much he loved him, and Phil was telling him how much he loved him, and saying goodbye. A little while later Brian called me and told me he felt he didn’t really say everything he wanted to say to Phil. I said, well, call him back. I probably gave Brian bad advice…

TP No, you gave Brian a good story…

BC So I’m sitting there, Brian calls back and Phil was like [mimics Phil yelling]: “What do you want? I’m tryin’ to die here!” [Laughter] Anyway, it was just typical: he wasn’t going to get saccharine or sentimental. I mean, he could be very sentimental but then he would close the door and say, “No, I’m not going to go there.” But I’ll tell you one thing, there was a tune on that record he was listening to, a Kern tune, with a fancy, sophisticated bridge, and I’m totally just trying to play like Phil—I’m trying to play with that kind of clarity, and swing, and ease, and just command. I thought, “Oh, there’s Phil, there’s some of what I was lucky enough to be influenced by.” And I remember thinking that as I was sitting there with Phil.

JJM After his death he was inducted into the DownBeat “Hall of Fame.” Do you think he would have been gratified and honored by that or seen it merely as so much jazz magazine “PR.”

BC Oh, he would’ve cared.

TP Yeah, I think he would have cared. I remember when Keith Jarrett was inducted, I was assigned to write the article on him for the issue, and I remember thinking that Keith Jarrett would just pooh-pooh it, but he didn’t, it meant something to him. I imagine it would have meant something to Phil, even if he might have treated it with due cynicism.

BC Yeah, it would’ve mattered. The magazine has championed the music for a long time, and to be included with your historic peers, it matters.

JJM Any thoughts or stories you’d want to add in closing?

TP Well, I hope that this book will stick around for a while, and that generations of musicians who didn’t have personal exposure to Phil Woods will be able to check it out. I think it’s a nice portrait of the times as well as being a portrait of a remarkably individualistic man. This is a moment when young musicians—and Bill can speak to this more than I because he’s in touch with the new generations, a new class every year—are potentially exposed to the entire timeline of music.

Phil, was in a way, a predecessor to those young musicians. He was a conservatory-trained musician, although I think something that scarred him was that he never got his degree. [Woods came within a few credits of graduating from Juilliard as a clarinet major.] I think that embittered him greatly, and he describes that in the book. He had a conceptual understanding of music history, through the twentieth century. He had his taste. But I don’t think, and Bill you can correct me, but I don’t think that his records are part of the academic canon—maybe they are in the places where he did jazz education.

I would like people to understand him as the extraordinary figure that he was, and take some inspiration from his example. And I hope this book helps to establish his posthumous reputation.

BC Well, I think that that is beautifully said, and true. I think he might be a little bit more a part of the canon in records like Further Definitions with Benny Carter and of course Charlie Rouse and Coleman Hawkins…

TP Dizzy’s big band things…

BC Yes, and Monk’s music, of course, Town Hall and others, such as Oliver Nelson, and in particular The Quintessence with Quincy Jones. So maybe those things a bit more than the quintet.

Phil Woods, 2007

But back to the book itself… the one thing about all of the young musicians who are fantastic musicians, and comprehensive musicians with all kinds of dynamics in their musicianship and versatility, the one thing they don’t have—which is no fault of theirs, it’s just the luck of when they were born— is that I was lucky to have played with people like Phil Woods, Jimmy Heath, Benny Golson, James Moody, and Benny Carter. I had that experience. I know what that felt like. I played with Phil Woods! Those apprenticeships just don’t exist anymore.

The point I’m making is obvious, that to get to sit with someone of that type of personality, intensity and depth and with that much history, and to get it from the horse’s mouth is something that our music is about. And it’s part of why, in my own humble way, I love teaching, because I’d like to pass on at least some of the things I got to experience and why they were worthwhile to me and maybe they’d be worthwhile to somebody else. But at 54 I’m just a kid, comparatively.

One of the great values of this book are the plusses and minuses of Phil’s undisciplined writing too—which has been put into some discipline by Ted’s framing it in the way that he has—but you still get the improvised quality that is the best part of what Phil’s writing is all about, which is that extemporaneous, let-it-all-hang-out and the feeling of the writing, which is the best part of it. And all of that gives you a feeling of Phil Woods the person, the intensity, and the artist.

All of that makes this book not just important to somebody who wants to be part of this music, but it’s also very entertaining. I couldn’t put it down, and not just because I knew and loved Phil as much as I did, but it’s fun to read! He pulls you in, he grabs you, and if you love this music and want to know something about its history—it’s not just starring Phil but it’s starring all these fantastic giants that he was around, and tells you something about times that are now gone. I loved reading about the early parts of his life, things that none of us would know without a book like this.

TP I think the early parts of his life could make like a nice film noir, actually.

BC Absolutely.

TP With some good, realistic stuff about the jazz. I think Phil could actually be a candidate for a sort of biopic with the right person.

BC Ultimately, I’m left with a very uplifting feeling having known him, and reading the book made me feel that special warmth. And not just that, you know, it was like going up to the lion in the zoo, you’re a little bit afraid of him too—you should be! He was intense and could be quite overpowering, and you may not agree with everything that he feels all the time and he wouldn’t care. That’s him. It’s the truth, and I think that part is pretty worthwhile.

I just want to say one more thing about Phil and that is that I love him forever. He was one of the most unforgettable people I have ever met in my entire life. He was some force of personality, and represented the highest standard of excellence all the time.

JJM I remember in an earlier conversation, Bill, you saying that his playing was ‘like the mark of Zorro.’

BC Well it was, it was searing. And if you can’t feel that, I can’t help you! [Laughter]

TP Well, Brian Lynch makes a comment in the book that Phil operated at the highest level of excellence on all levels, that he had no weak spots.

BC That’s one of the most beautiful things Brian wrote in his postlude about how many artists make the most out of hiding their weaknesses while underlining their great strengths. And that’s not necessarily a putdown, it can be a very great thing; but with Phil there were none of those things. He was that complete a musician.

On any given night, Phil was so virtuosic that he could just flip the switch and just simply play well. He could also flip the switch and play absolutely brilliantly, and he could also flip the switch and get into some creative mode in which he was striving for something he had never played. I saw him do all of these different things —I saw him on a good night, a great night, and an inspired night, and sometimes all of those different things within one night. But he had a Fred Astaire-like command—it always looked real easy.

.

___

.

photo by Brian McMillen

Phil Woods, July, 1986

“And so my story is told. My tale has ended. I have tried to speak the truth as best I could. The seams of my life might show, but I believe an honest tailor sewed the stitches. Like all humans, ‘of regrets I have a few.’ If an epitaph were needed, I would opt for what Miles Davis said to Ira Gitler: ‘That cat can play!’”

-Phil Woods

.

.

Listen to Phil Woods play “You Must Believe in Spring” from the 1975 album Michel Legrand Live at Jimmy’s. Woods considers this to be one of his most important (and favorite) recordings.

.

.

___

.

.

Life in E Flat: The Autobiography of Phil Woods

(with Ted Panken)

.

.

___

.

.

Bob Hecht put together this Spotify playlist featuring many of Phil Woods’ most important, memorable, and enjoyable recordings

.

.

Thanks to Brian McMillen for his gracious consent in allowing use of his photographs of Phil Woods. A resident of the San Francisco Bay area since 1955, his photos have been used in books, magazines, LP and CD covers, as press photos for artists, and by artists in other media.

You can visit his website and view his portfolio of jazz musicians by clicking here

.

.

Thanks to Cymbal Press Publisher and CEO Gary Stager for his assistance with this interview.

.

.

This interview took place on December 29, 2020 and was hosted and produced by Bob Hecht.

.

.

.

.

One comments on ““Life in E Flat” — a conversation about Phil Woods, with pianist Bill Charlap and jazz journalist Ted Panken”