“Lay Out,” a story by Barnaby Hazen, was a finalist in our recently concluded 48th Short Fiction Contest. It is published with the permission of the author.

Lay Out

by Barnaby Hazen

You’ve played this gig at the Tennyson Lodge at least a hundred times by now you figure—three years times twice a week, Wednesdays and Thursdays. You just took a solo and now The Kid is thumping on his oversized instrument, oversized by comparison to his body. He’s a five-foot-nothing of a chubby student bassist having joined the quartet two weeks prior. His dark, stylishly teased hair is stuck in place by product, his eyes just barely open and he rocks left to right in a manner offensive to you for some reason.

You don’t need a reason. You’ve been doing this long enough to call it like you see it and The Kid is nothing more than a vaguely promising hack. You might want to talk to him on break, get a better idea where his head is at, but meanwhile he’s wiggling around and you kind of hope he gets caught under a subway somewhere, but there aren’t any subways in Phoenix. You’re sick of this town and you know it.

Is he taking another chorus? Yes, he’s taking another chorus. You’ve been keeping time with brushes and you’re tired of what he’s playing so you pull out for a bar or two, then grab your sticks. He looks at you funny so you fire back at him on your kit—he’s on a triplet run, you hear him hitting a wall so you throw a sixteenth note fill in the hole. He looks at you again and digs in.

Good. That’s what it’s about.

You keep putting odd fills in his holes, pushing him to think about what he’s playing. If the audience could hear the instruments’ intents, your kit would be saying, “Is that all you got?” which in the old days was the same as saying, “That ain’t all you got,” but now you don’t know, you just don’t know. And that bass would be saying something back at least, maybe something like, “I don’t know who you are but you sure did show up to this gig in a bad mood. I’ll see what I can do—I’ll try to even your night out some way.”

And damn if this kid isn’t going to take another chorus, which to you sounds like the instrument saying, “Look at me, I’m a bass, and I may not have much to say but you’re going to hear a lot of it tonight,” and so you start stabbing at him with your drums, giving him something to really play off of; the kind of thing that would have made your late partner, Charlie—not Haden, but a mother none the less; maybe deeper sometimes—he would’ve shot back at you with a look something raw, between a smile and a grimace, and then burned if you were to start playing around him like that; but you wouldn’t have and anyway it’s just that’s what would have gone down with a cat that put some real heart and time into his instrument.

Halfway through the fourth chorus all you’re thinking is to discourage this kid anymore. You’re not proud of it, but you’re not going to sit there and pretend what’s going on is cool, even if the tall white man up front, Natty, guy that puts you to work and announces your name every week like it means something (and about that, doesn’t it seem like he’s more proud of himself for hiring you, than he is digging on what you’re playing now?), but even if he wants to act like it’s cool, where you came from this wouldn’t fly.

The look on The Kid’s face, like he just learned the phrase and had been waiting for a chance to say it; like he had the first bit of standing to produce such a demand or disrespect you, and there aren’t enough subways in New York to satisfy what you’d like to see happen to the ingrate, back and forth across his useless little hands and smug, tidy face; no mistaking the words, “Lay out, old man,” and that was the last gig you’d play with him, even if he didn’t get his ass kicked by Natty right there on stage like he should’ve.

Did Natty hear it? That’s the big question as to whether you come back next Wednesday. If he heard it and he’s pretending not to, you had better catch some hint about it, even if he doesn’t come right out and say it—about how that kid won’t be back and not to worry, he’s got another player in mind. Or maybe he asks you, for a change, who you think ought to be on the gig. Though Phoenix still isn’t your scene, it would be nice to know he thought enough to ask.

And if Natty hears about this over the weekend and doesn’t see fit to make it right, maybe that’s it for you, period. Maybe it’s time you stay home for the rest the of your life.

***

You’re poolside with some Nicaraguan overrun batch; you get cheap cigars even though your old lady, Sandie, offered her credit card to your account on the internet. You use your gig money for that and golf course dues. It’s been a while since you’ve been to the course, but you want to keep those two expenses your own because it feels like a reason to keep playing drums.

And speaking of that, Natty does call and ask about the night before, how you seemed to get off in a hurry. You tell him what the kid said word for word, even though it tastes wrong coming out of your mouth, and Natty says he’ll deal with it and he’s a big guy so you assume you won’t ever have to see that boy again and leave it at that.

And speaking of kids, Eddie, your grandson is in town for the summer and coming by soon. Sandie is in the kitchen putting something together and listening for him. In your study, there are vinyl records set aside you’d like him to hear. You played in a funk band in the 80s and he’s been doing some kind of DJ thing or another, and you figure there must be something like funk in pop these days even if there ain’t no Qunicy Jones on the scene anymore, at least not like he used to be, on everything.

You listened to one of those records you set aside a couple hours ago and you weren’t so hard on yourself as the last time you heard it; you think maybe there was something happening there. And it’s funny how you can take a little time off hearing some record maybe you beat yourself down about before, thinking you ought to have been a little less busy here or there and suddenly it’s all right. Must have to do with where your head’s at when you hear it, but what good is that to know? You going to start wearing a mood ring to check on before you break out your old tracks?

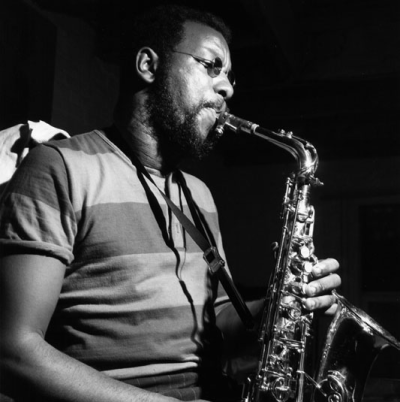

Jimmy Reed and the Swank was the band that took your eye off jazz in New York for a few years and you never quite found your way back. You don’t regret those tours but it was a shame to miss an Ornette Coleman album by manner of being off your game for certain chops. It’s too painful to think you might have been on Caravan of Dreams or whatever came after that so you push the thought away, relight your cigar and wish Eddie would show up already.

When he does you hardly recognize him at first—he’s got some kind of flashy mirrored sunglasses on and he must be around twenty by now. He’s a light-skinned brother, always spoke like a white kid but now he has hip-hop coursing through his posture and speech.

“Yo Grandpa,” he swaggers toward you, smiling.

“Eddie! What’s the good word?”

“Nothing but the rent. Damn, I forgot to bring my trunks.”

“Oh, we’ve got something you can use I’m sure.”

“That’s all right, I’ll just be here a minute.”

Your son—Eddie’s dad—is Edward, an entertainment lawyer. Maybe Sandie accepted some money—either as a gift or a loan—from your own boy when you were living in Los Angeles, but you’re not sure. This might’ve happened before her parents both passed away in the same week and she had family money to start over with.

And maybe the feeling that you’ve lost your love of playing is just a passing one, like thousands before, and you’ll wake up one morning soon, or show up to your next gig and realize how stupid it is you even think that way.

Eddie doesn’t ask to try your cigar, and that’s good because it would bother Sandie and she’s keeping an eye out through the kitchen window, probably finishing up some snacks to bring out to the pair of you. Your bare feet are dangling from a beach chair into the shallow end of the pool. Eddie pulls another chair up, near enough to smell the smoke and kicks his basketball shoes off using his heels. He pulls his sox off with his fingers and says, “This pool is the bomb. I like it better than our indoor pool in Griffith Park.”

“Yeah, I know some people can’t take the heat but I’ve always liked it.”

“Me too! I have too! I guess I got that from you cause mom and pops both hate it.”

“Oh yeah?” you say, and the smoke coming out of your nostrils feels a little too hot. “I guess that’s right. Back in New York I was always telling your dad to put a sweater on instead of busting me with those heat bills.”

Eddie snickers as if he knows what it means to struggle to pay a bill yet, or as if it seems likely he ever will. His mom, Irma, told him she thought he should travel before he went to college, and that’s all he’s done since—Europe, Africa, you’re not even sure where else he’s been, maybe Cuba. He should have brought you back some cigars, you’re thinking when Sandie comes out with a tray.

Your extended mixed race of a family is generically represented in neat, suburban sections on that tray: there are taquitos and salsa, bringing Eddie’s mom, Irma to mind; crackers and cheese, making you think of Sandie’s fancy white New Yorker upbringing; and of course some leftover cornbread and chicken wings from last night, all about you.

Your cigar goes out again while the two of you take care of most of what’s on the plate. You say you’ve had enough and then Eddie leans in and polishes off the rest following a comical flash of surprise, and casual acknowledgement of free reign: “All right, then.”

You suggest a trip inside. You put your flip flops on and lead him into the room where you set those records aside. On top is Jimmy Reed and the Swank: Loaded Boat Full of Funk. The artwork on the album was a reference to The Beatles’, Yellow Submarine, because Jimmy wanted to cover “Hey Bulldog” and it ended up making Loaded Boat, first track even. There are animated versions of the four band members, with Jimmy holding his fingers up in the same formation as John Lennon’s. Your likenesses are positioned as the Beatles were on the mound, but behind you are cops dressed like Blue Meanies on your right and a couple of obligatory 70s sex goddesses with giant afros on the left.

You don’t know what you were hoping for by putting this on, but Eddie is pacing around the room looking at some of the photos, such as with you and Thelonious in ’72. Eddie clearly doesn’t know what to do with himself, after taking a little tap on one of your Zildjian cymbals with his likely very greasy forefinger.

The lessons you gave him when he was ten he seems not to remember.

Next he looks through a few jazz history picture books, then hears a break he likes on “Bulldog” and says, “Damn, that’s tight. Hold up, Grandpa, can we go back and hear that again?”

“Sure,” you say, and start to get up.

“That’s all right,” he says, “I can get it.”

You sit back down slowly, while he finds the spot he likes—a drum and bass groove, very straightforward for the style. He’s so taken with it he’s bobbing his head, deftly measuring a loop out of those few seconds of music. He repeats it several times, cranks the volume and the bass; scratches back and forth a little and suddenly something’s not right for you.

You think maybe you’re just old and bothered by the way he’s picking at your record but it’s not that at all, because you felt this once before from the sounding of a gong at that Berlioz concert of ’85; it’s a Deja vu leading up to a heart attack you think; you don’t know when it’s going to hit but for the second time in your life you’re certain you’ll be going by way of heart attack, maybe right here, with the bass thumping; it might just happen right this second if you don’t hurry up and leave the room.

“Gotta hit the head,” you say, but Eddie hardly notices.

***

Do you remember how it started? A ten-year-old hammering triplets and sixteenths on a Goodyear practice pad, making a quick impression on some skinny, bearded, awkward white dude by the name of Tom. That’s all you remember of his name—you called him “Mr. Tom”—or you would have invited him to one of your New York gigs once you started playing out. He saw enough in you to offer private lessons on the shiny kit in his home studio so you wouldn’t have to just wait your turn once a week for your shot at that rickety old barebones thing he brought to the after-school classes.

Next you were in band in Jr. High, jazz band in high school; then gigs, and plenty of them because you were hot and you stayed that way for about thirty years; up until you moved to L.A. you think, and that’s when everything started to slide. You had to give up the drink even, even the drink; you thought you’d be fine after quitting the white stuff, but then you were waking up to your old lady looking down at you in a combination of amusement and terror, in some parking lot outside the joint where you stopped for a quick drink on the way home was all: “I thought I could handle it,” you told her one morning and that was that.

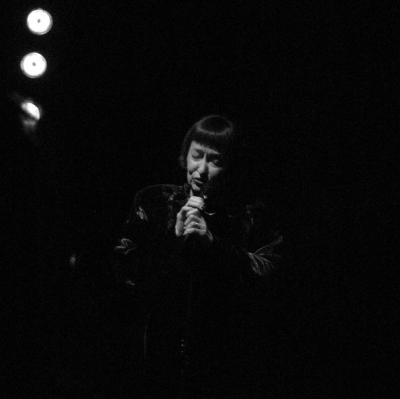

Now you’re at a college function. You had more fun getting ready than you did arriving and setting up. You remember Sandie was fixing your tie, and smiled at you with those precious eyes, looking past the Crow’s Feet: angelic, rare, like turquoise, and she said, “You’ll knock ‘em dead, Mort,” and planted a kiss, which you can’t even take for granted anymore, and it made you think back on those days when she was dripping with sex at just about every show, even if it were in Harlem, so unscrupulous bandmates might have been looking for an angle with her while you pretended not to notice; while you were probably off trying to talk on some serious spiritual level with Amiri Baraka just off stage, and acting the fool with him given all the blow you took back then; but here she still was after all those years, neither one of you really having slipped up, give or take, you don’t even care anymore. You remember just a couple hours back, the way she looked at you when she was giving her pep talk about how this thing could lead you to the golden egg of “Master Seminars,” which was bigger money than probably a month of your little gigs. You can’t bring yourself to care where it leads, whatever this function is—but with her, it felt like old times for a minute.

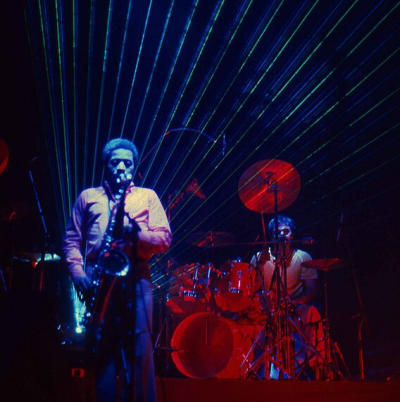

And you do, you hate the vibe at this college—something in the lighting and the way you were introduced by Natty again, “A legend from the golden years.” Still, you eventually hit a good run, when you and Natty are trading fours on “Blue Trane.” You’re playing fierce, the both of you.

Then something catches your eye—it’s The Kid, the chubby bassist, with all kinds of nerve and no heart, sitting in a crowd of probably two hundred jazz performance students on those crummy fold-out cafeteria chairs. He’s sulking something awful, like he’s been sitting in his dorm room crying for days, then finally stepped out for a trip to a gun auction. You heard Natty nearly made the kid soil his pants, by hovering and telling him, “Do you have any idea how lucky you were to be playing with Morton Ellis? Well now you’re lucky I don’t break those stubby little fingers off for you.”

Next thing your left arm is seizing just over the snare, like something you’ve never felt before. Yeah you had trouble with either arm, here and there, after a long night and you’ve put ice on them, and Sandie’s always telling you to get to a doctor but this time there’s tingling all over and then your hand is empty, hollow, nothing left.

Your heart is racing, and you’re grateful when it’s Natty’s turn because you think maybe this is it, like that old Redd Foxx show, and you’re grabbing your chest and falling off the stool just as you think that, and those crummy florescent lights just over you are the last thing you see before you’re squinting at medical professionals from the inside of a screaming ambulance.

***

Maybe you couldn’t have been a contender, but you miss contending.

You’ve been horizontal in your studio for the past three days. God bless Sandie for coming in to check on you, probably wondering if your body has simply evaporated, given how you respond whenever she slinks in with your coffee and some frozen food snacks on a tray you might pick at. Last time she said, “I’m here if you need anything, Morty. Not just food…or a kiss on the cheek, but anything.”

“I know,” you managed, “thank you.”

“Do you want to talk about it?”

“Not yet, Sandie. But again, thank you.”

That kid, you thought his face might be the last thing you would ever see, but then the lights, and the ambulance; the hospital, and the doctor’s cheerful delivery of the two most humiliating words you’ve ever heard in seventy-two years of life: “Panic attack.”

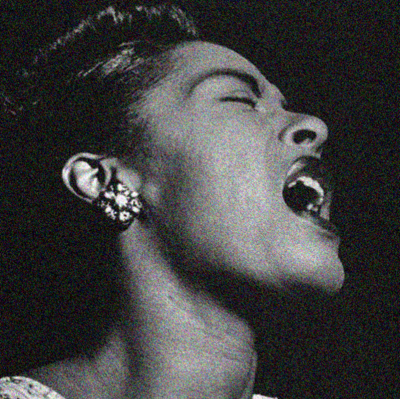

Like at Slug’s Saloon: you must have been about twenty-two when Alan Shorter looked over after you comped his solo—it was a moment of rare understanding, that you knew, you both knew you had given something to one another that evening. That’s when you thought maybe you were in the running to make a wave on the New York jazz scene. That’s all you wanted to do anyway, was get in with the cats that was happening, and you were looking all right in ’73 for that, but then you got on a bus with a funk band right when disco hit, lost your grip on New York—anyone who started to know you forgot who you were—and you never found your way back. And these names that big oaf, Natty, the names he likes to throw around every time he gets on stage with you, they’re just romantic self-affirming ghosts to him, while to you they’re bitter reminders of a path not taken—of what you couldn’t have been, but miss thinking you might.

The doctor was a short, confident brother with a meticulously cut goatee and moustache: “It’s not unusual for this sort of thing to happen,” he said, looking briefly back down at his report, and pursing his lips matter-of-factly, having spoken news that should’ve been a relief, but which he could see was no relief to you of any kind. “Given how long you’ve been playing drums, the sudden loss of use was a great shock, and might easily have been enough to cause a wave of panic. As for the hand, and forearm, there are surgeries you can consider, if you want to come back and get a full workup,” and here he grimaced, again with that doctor breaking news air about him, though finally sounding a little black, “but I’d bet money this carpal tunnel’s been fixing to chop you down for a good little while now.”

Pamphlets on repetitive motion disorders are on your bookshelf somewhere, and the faces on the television look like those of zombies from a 70s horror flick; also kind of like that kid that was staring at you right before you folded and reached this moment of probable retirement. One cold taquito out of five is half eaten when the next tray comes around, and Sandie mentions that Eddie’s on his way, just wanted to check in on you and would that be okay?

You nod lethargically and fall into a familiar daytime sleep with the TV too loud. It will wake you up with news about a car accident on I-17, just enough to disturb you, but not enough to get you to reach the remote on the floor under your futon couch, where it must have fallen when it slipped out of your good hand.

There must be someone else, you’re thinking. There must be someone to take over what you almost did.

Sandie brings Eddie to you like she knows something you don’t about the visit. Could just be she likes to see her family looking after one another, and you know you’re lucky to have her and you’ll have to get up and tell her that before another day goes by with you rotting on the couch in front of this television, barely even making it out to smoke by the pool; that’s how bad this is, that’s how far you’ve checked out of this life and you know it’s got to be hurting her and you’re sorry.

Even if what you almost did was damn near nothing in the big picture of music, jazz, and everything Amiri said came with it—it was important to you, and it’s over—so now there must be someone a little younger, healthier; maybe not even a drummer, could be anyone, but with the same passion for playing and performing as you had when you were twenty at Slug’s Saloon— and then that other night when Elvin Jones came over to your table and rapped with you after you sat in—or the world doesn’t make any sense.

Still the face comes back to haunt you—that vacuous expression of humiliation and hatred—and the words he said at the Tennyson, like the death card of a street corner tarot reading you laughed off until a piano came crashing down on your head:

Lay out, old man.

Eddie is sitting next to you, and you are slumped rather than prone to make room for him. You’re enjoying the sound of his laughter to a movie about a white guy trying to win over a black girl’s angry father, and he seems not to know that what happened to you was a sham—a trick your body played against your mind’s eagerness to move on from this world. He was asking questions in a soft voice, like, “So the doc says you’re going to be all right, that it wasn’t that bad?” He doesn’t understand the shame of it all, and that’s welcome but then he gets up, with that restlessness that made you nervous before, and he starts talking music:

“So I was rapping with my pops, you know, and he was telling me that the sample off of the record you lent me, you know that bomb-ass, sorry, that bomb funk record you did, he said that was a Paul McCartney jam, and I’d have to go through the Michael Jackson estate or something…”

Lay out.

After how many years of six-hour days playing rudiments, taking every beat in every exercise book Mr. Tom every put in front of you…?

“And then he said that if I got someone to perform it, you know, to play something a lot like it, well then…”

And here’s your own flesh and blood reducing it all to a four-bar sound-bite, to be stolen by a machine. His voice is fading and you feel if you let it fade too much you’ll slip into another attack, so you try to stay with him, to stay with the world.

“But then I was thinking, you know, if you get to feeling better, maybe I could just record you, and we could put something together, or maybe even a whole bunch of samples, and I would give you credit and everything…. You never know, this internet is such an open market, so you never know what’s liable to blow up and get viral, with the right branding and shit; I mean, sorry….”

You sit up. He’s asking you to record short drum parts, for pieces of music he might use to produce rappers; or that’s what you’ve gathered, anyway.

Maybe there is someone out there picking up where you left off, and maybe the world makes sense if you have a big enough scope and back far enough away to see it all; but Eddie, an unlikely candidate for such though he may be, is reaching out to you now, and you like having him around, so you hear yourself saying, “Now hold on a minute, Eddie, and let me ask you this: why would you want to wait until I’m feeling better? Why do you need to wait for me to play them drums?”

“You mean…you could…?”

Your voice sounds weary, but without despair: “Why don’t you just sit down at that kit right there? Yeah, that’d be all right—just sit right down and I’ll remind you of a few things I taught you when you was just ten years old. Remember that, Eddie?”

_____

Barnaby Hazen is an award-winning author, professional musician, and aspiring anarchist. His background in music includes a Masters in Jazz Composition/Jazz Studies, out of the Prescott College Humanities Dept. He lives with his wife, Sarah, in Taos, NM, where he teaches, performs, and writes for a more a less full-time living. His website is https://barnabyhazenblog.wordpress.com/