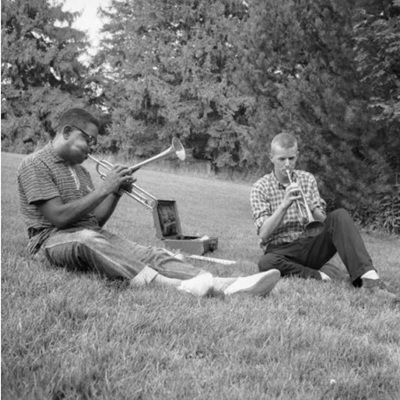

Larry Tye,

author of

Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend

____________________

Leroy Satchel Paige was the most sensational pitcher ever to throw a baseball. During his years in the Negro Leagues he fine-tuned a pitch so scorching that catchers tried to soften the sting by cushioning their gloves with beefsteaks. His career stats 2,000 wins, 250 shutouts, three victories on the same day are so eye-popping they seem like misprints. But bigotry kept big league teams from signing him until he was forty-two, at which point he helped propel the Cleveland Indians to the World Series. Over a career that spanned four decades, Satchel pitched more baseballs, for more fans, in more ballparks, for more teams, than any player in history.

In Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend, award-winning author and journalist Larry Tye untangles myth from truth about this flawed yet majestic man. Tye shows us Satchel as a self-promoter who selflessly fought to guarantee his teammates richer paydays. He was a Casanova with outsized appetites and a devoted father who towered over baseball with his skill as well as his shrewdness.

In Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend, award-winning author and journalist Larry Tye untangles myth from truth about this flawed yet majestic man. Tye shows us Satchel as a self-promoter who selflessly fought to guarantee his teammates richer paydays. He was a Casanova with outsized appetites and a devoted father who towered over baseball with his skill as well as his shrewdness.

This new book also rewrites our history of the integration of baseball, with Satchel Paige in a starring role. While many dismissed him as a Stepin Fetchit, Satchel was something else entirely: a quiet subversive. He pitched so spectacularly that he drew the spotlight first to himself, then to his all-black Kansas City Monarchs, and inevitably to the Monarchs rookie second baseman Jackie Robinson. In the process, Satchel, even more than Jackie, opened the door for African Americans to the national pastime and forever changed his sport and this nation.#

In an August 25, 2009 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician contributor Paul Hallaman, Tye talks about this story that speaks to fans of sports history and American culture.

*

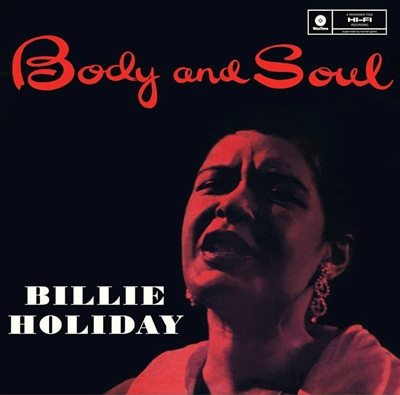

“The truth is that Satchel Paige had been hacking away at Jim Crow decades before the world got to know Jackie Robinson. Satchel laid the groundwork for Jackie the way A. Philip Randolph, W.E.B. DuBois, and other early civil rights leaders did for Martin Luther King, Jr. Paige was as much a poster boy for black baseball as Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong was for black music and Paul Robeson was for the black stage — and much as those two became symbols for their art in addition to their race, so Satchel was known not as a great black pitcher but as a great pitcher. In the process Satchel Paige, more than anyone, opened to blacks the national pastime and forever changed his sport and this nation.”

– Larry Tye

________

PH Satchel Paige’s childhood was spent in Mobile, Alabama

LT Yes, Satchel Paige came into the world at a moment when Mobile was being transformed from one of the more tolerant deep south cities, into a bastion of Jim Crow Alabama. Under Jim Crow, it became a world of legally prescribed segregation, where blacks and whites were banished to separate quarters, whether it be the schools they went to, the parks they played in, the libraries they took books out of, the public transportation they rode, or the baseball fields they played on. And, during the very year of Satchel’s birth, 1906, there were a number of lynching’s in Mobile, so he came to the world at a very difficult time to be black in Alabama. It was even more difficult for Satchel, since he was only one of a family of 12 kids, raised by a mother whose income came from work as a washer woman, and by a father who was an occasionally employed gardener.

PH One of the ways Satchel tried to help his parents make ends meet was by fishing.

LT He contributed in a lot of ways. He would go fishing and bring back a fish for the family, or he would go out into the alley and collect old Coke bottles and turn them in for a penny or a nickel. Importantly, he would go down to the local L&N train station, where he would carry people’s bags — the way an old red cap would have done in those days — for a dime a bag. Satchel learned to set up a system of ropes and pulley’s that allowed him to carry three or four bags at once, which meant he could earn three or four dimes at once. He did that to a point where his friends would say that he looked like a walking suitcase tree, or a walking satchel tree, and the name “Satchel” stuck. He kept that with him for the rest of his life.

PH As a young man, he got into trouble and was sent away to reform school.

LT That’s right. He got into a couple kinds of trouble. One was that he spent so much time out fishing and out working at the train station that he was seldom in school. So, he was on a list for truancy. Also, when he worked at the train station, he would occasionally go beyond just moving a suitcase to actually stealing it. At times he would also steal trinkets from a five-and-dime store. He eventually got caught one time too many, and he got sent to court, where they sentenced him to five years at the nearby reformatory, a place that was segregated like all of the institutions were at the time. It was known as the Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Lawbreakers. Satchel spent five years there.

PH This school was significantly influenced by the principles of Booker T. Washington, wasn’t it?

LT Yes. It was set up by Booker T. Washington, and populated with kids that Washington and the local “colored women’s clubs” of the era recommended. The idea of a reform school sounds Draconian, but they were set up with Washington’s ideals of self-help — that every black child, like every black adult, should figure out what they do well, and to do it so well that even in an unfair Jim Crow world, you could succeed. And, in this reform school, Satchel learned that he could pitch a baseball better than just about anybody. So, he was a poster child for Booker T. Washington’ s notion that you have to do something and to do it the best that you can. Satchel said that he traded five years of his freedom to learn how to pitch a baseball.

PH Shortly after he came out of reform school, he was discovered by a man named Alex Herman from Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he became a professional baseball player…

LT Yes, that was in 1926. When Satchel Paige was about to pitch his first game, he showed up in Chattanooga with everything he owned — one pair of pants, a pair of underwear, a pair of socks, and one extra shirt. He rented a room at the rate of two dollars a week, which was more than he ever spent on anything. He didn’t store anything in the closet of that room for the first two months, because everything he owned could fit into a paper sack.

When he showed up to the ball field to pitch, his feet were so large that they didn’t have regulation cleats to fit him — he had to wear a pair of street shoes with spikes nailed to the bottom. He turned up on the baseball field with his hat tilted to the right, which was the way he wore his baseball hat, and he was all arms and all legs. In those days he could pitch a ball as fast as anybody, but he was also as wild as anybody. Alex Herman was from Mobile, and he managed and owned the Chattanooga White Sox. He brought Paige to town and had him out there every day before the game, setting up three Coke bottles 60 feet, six inches from where he threw, practicing his pitching by knocking over the bottles. He also practiced every day, before and after the game, throwing a baseball into a knot into a fence about the size of a grapefruit, where the ball barely fit into that hole. He got so he could throw nine out of 10 baseballs through that hole. He took his natural-born skills of throwing fast and hard, and refined that by throwing accurately, so by the time he left Chattanooga two years later, he was as good as they got in the Negro Leagues. And, if he had the chance, he could have shown that he was as good as they got in professional baseball of any color, at any level.

PH After a few years pitching for the Birmingham Black Barons, he wound up in 1931 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, pitching for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, which was run by a character right out of Damon Runyan — if Runyan had written about people of color — named Gus Greenlee, who was the numbers baron of the Hill District in Pittsburgh. Paige was in the center of a cultural renaissance going on in Pittsburgh at this time, wasn’t he?

LT He was, and it was really quite extraordinary. In those days, the Hill District of Pittsburgh was one of the centers of black culture in America, and it was definitely the center of the black sports world. Pittsburgh was the only city that had two Negro League teams — the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a team Satchel played on that was owned by a numbers runner named Gus Greenlee, and their ultimate opponents the Homestead Grays, a team owned by Cumberland Posey which was made up primarily of workers at Andrew Carnegie’s Pittsburgh Steel. It was an extraordinary time, because there were ongoing battles between these two great cross-town rivals. If you were a black American living in Pittsburgh during that time, the coolest thing that you could do was eat at Greenlee’s Crawford Grill, and then go out and watch a ballgame with Satchel Paige pitching against the Homestead Grays and the great Josh Gibson. You could watch a pitcher throw a baseball 100-miles-per-hour to a batter who could hit a home run farther than Babe Ruth. Pittsburgh was a center of incredible action and activity, and Satchel was in the center of it all, the way he always was.

PH Shortly thereafter, Satchel — always searching for a new experience and a bigger paycheck — was recruited by an auto dealer in Bismarck, North Dakota, to play ball out there. This broke a couple of barriers, didn’t it?

LT Yes, it did. The first barrier it broke was having great baseball played in place like North Dakota, where we don’t expect to see great baseball. They were playing semi-pro baseball there at a higher level than anywhere in America. The other barrier it broke, of course, was having an amazing black ballplayer like Satchel Paige play there, where only a handful of blacks actually lived. And, the idea of bringing in the greatest African American ballplayers to play in Bismarck was quite extraordinary.

In addition to the ball that they were playing out there, they went to national tournaments where black and white ballplayers not only competed against one another on the same field in the middle of the Great Plains, but they actually played on the same team. This was simply unheard of — and it was a generation before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier! The fact that this happened and that the sky didn’t fall from it set the tone for what would happen a generation later in the major leagues. It was really quite brilliant, and again, Satchel was at the center of the action.

_____

PH Your book is rich in description and your research is very meticulous. You write about his barnstorming years in the California Winter League, and his duels with Dizzy Dean, among so many other great stories and times in his life. But, in the interest of time, I want to jump ahead to 1934, when he was recruited by Raphael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic…

LT Trujillo basically controlled everything that went on in the country, including baseball. He had formed his own team in the capital city he named after himself, Ciudad Trujillo, which is now known as Santo Domingo, and was determined to beat the other two leading teams in the Dominican Republic. It was a year before he was due to run for re-election, and he understood that even if he didn’t care much about baseball, the Dominicans did, and that winning a tournament could do a lot to boost his image. In order to do this, he brought in the best ballplayers “for rent” from around the world — who happened to be black Americans, including the great Satchel Paige. He went on that year to lead Trujillo’s team to a narrow victory over their arch opponents. Satchel made the whole thing seem like it was a question of life or death, that if he didn’t win, he might be put in front of a firing squad. It was never that dramatic, but it made for a great story, and the truth was that Satchel did win.

PH There is so much contradictory information concerning Satchel Paige “the man” versus Satchel Paige “the legend.” How were you able to sort all of this out?

LT I was a reporter for 20 years, and this was my fifth book, and I have to say that this was the toughest one in terms of trying to separate fact from legend. I was able to do it in a couple of ways. One was assembling everything that every journalist had written about Satchel over the years — and not just when he played in the Negro leagues, but also when he pitched in small towns, barnstorming across America. I pieced together all the written records in every magazine or book that ever talked about him, but more importantly, I interviewed over 200 aging major leaguers and Negro Leaguers who played with or against him, using their memories to fill in the gaps of the written record. So, while it was one of the toughest jobs I have ever taken on, it was also one of the most enjoyable reporting jobs I have ever taken on.

In the end, what I concluded was that about 80 percent of his extraordinary claims were true, which of course raises the question of why did he embellish the other 20 percent? My “pop psychology” theory is that he understood that the great white players of his era — Babe Ruth and Joe Dimaggio, for example — had journalists following their every move, fanning their legends. Satchel understood that he had to fan his own legend. He was a terrific story teller, and at times, when he was telling the same story for the fifteenth time, he couldn’t resist tweaking it and embellishing it to the point that the story turned out differently in his own two memoirs. They were written 15 years apart, and by the time he got around to writing the second, it was as if he never bothered to check what he said the first time. The essentials were always there, but, at the edges, there could also be exaggeration.

PH You called some of what Satchel “the legend” accomplished “super-sized feats.” For instance, calling in the outfield while he pitched, the 10 penny nail act, and throwing strikes over gum wrappers. All of this was part of the showmanship that was essentially required by Negro League baseball to bring people into the park, wasn’t it?

LT That’s right. I would like to tell your readers about some of the things that he did. He was so confident about his ability to strike batters out, at times — sometimes against lousy teams, and sometimes against good teams — he would actually call his outfielders into the infield and tell them to sit down and talk, play cards, or do whatever they wanted to do. He was essentially daring the batter to hit the ball out of the infield, and if they did, it would be an automatic home run. He was telling his opponents that he was so confident in his pitching, he was convinced that he could strike the batter out. And, most of the time he would either strike out the batter or they wouldn’t hit it out of the infield. At times he was so confident that he not only called in his outfielders, he called in his infielders too, leaving just himself and his catcher.

The 10 penny nail act you mentioned involved him sticking a series of nails in a 2″ x 4″ that he set up behind home plate. The nails were barely sticking into the board. He would then throw the ball so accurately and so hard from the pitcher’s mound that the nails would be driven straight into the board.

He did these things for two reasons, one of which was, as you said, to attract fans. He would set these tricks up before the game because he knew people would come early to see him, giving them a brilliant show before the game even started. He showed the fans how good he was and gave them extraordinary entertainment even beyond what they paid to watch the baseball game. The other reason he did this was because he knew that his opponents would be out there, warming up early, and when they saw him do these things, he knew it would intimidate the heck out of them. These kinds of things insured that the stadium was always full when Satchel pitched.

PH In fact, he was such a great gate attraction that even after his arm went dead in Mexico in the late 1930’s, J.L. Wilkinson, the white owner of the Kansas City Monarchs, brought him over to pitch for what was called the “B” team — or the Baby Monarchs. So, even though his arm was damaged to the point where he could only pitch an inning or two, he was still so popular that people would come to see him play.

LT He was so good that, as you say, he could fill a stadium even when he wasn’t pitching. People would show up just to watch him, and for the rest of Satchel’s career, Wilkinson had faith that even if he didn’t make it back as a player he would still draw big crowds as a member of the team. Well, Satchel did make it back. After a season of playing with the Baby Monarchs, Wilkinson brought him to Kansas City to pitch for the real Monarchs, and Satchel, despite pitching with what today would likely be diagnosed as a partially separated shoulder, pitched brilliant baseball for years for Wilkinson. Wilkinson, even more than Gus Greenlee, turned out to be a father figure and a guy Satchel could count on for big paychecks, great advice, and for generally caring about him.

PH And it is ironic that he was a father figure because his partner, Tom Baird, was allegedly a member of the Ku Klux Klan, correct?

LT That’s right, but that is just one of the many horrible contradictions and ironies of the Jim Crow era of racial segregation.

PH This would be a good time to bring up Branch Rickey’s decision to choose Jackie Robinson to break baseball’s color line. The question, of course, is why didn’t Rickey choose Satchel Paige?

LT There are a number of answers. In fairness to Rickey, in 1945, the year Rickey first signed Robinson, Satchel was 39 years old, was not having a great season, and it was easy to conclude that he was washed up. More importantly, Rickey was looking for a straight-laced guy who lived as conservative a lifestyle as he did. He favored prohibition, didn’t drink, and in Robinson, Rickey saw a young, college-educated young man who seemed like the kind of guy who would keep his mouth shut and do just what Rickey wanted him to do in the early years of integrated baseball. Satchel Paige, on the other hand, was not about to keep his mouth shut, and he was not about to go and spend two years away, as Robinson did, playing in Montreal in the minor leagues before being called up to the Dodgers. He was just not Rickey’s kind of guy.

PH What was Satchel’s reaction to the signing of Robinson?

LT His first reaction was the perfect, politically correct one — he said Rickey couldn’t have picked a better guy. But he must have had heartburn when he said that, because he didn’t believe it. He believed, for understandable reasons, that he, Satchel Paige, was the one who had drawn the attention of the white press, of white fans, and of white owners like Rickey to the Negro Leagues. It was he, Satchel Paige, who had brought the spotlight to the all black Kansas City Monarchs, and it was only because of him, Satchel Paige, that Branch Rickey or anybody else knew about Robinson, who started that season in 1945 as a second string second baseman on the Monarchs.

PH You said that Satchel wasn’t Branch Rickey’s type of guy, but he was Cleveland Indians’ owner Bill Veeck’s kind of guy. Tell us about Bill Veeck and his choosing Larry Doby and Satchel Paige to break the color line in the American League?

LT Let’s travel back to the summer of 1948, to what may have been the tightest pennant race in the history of baseball going on in the American League. It was the Cleveland Indians, owned by Bill Veeck, facing off against the Yankees and the Red Sox. Veeck loved to poke his finger into the eye of his fellow owners. He was a huge showman and was willing to do whatever it took to fill a stadium. He had a very novel idea on how he could break away from the Yankees and the Red Sox in that pennant race, and it was, to bring in for a tryout, this aging pitcher named Satchel Paige. He brought him in one morning to an empty Memorial Stadium in Cleveland that, when filled, would seat 78,000 fans, but on that morning, it had three people in it — Bill Veeck, Satchel Paige, and the player-manager of the Indians, Lou Boudreau. When Boudreau saw Satchel Paige, and realized he had been brought down early that morning for a tryout for this aging African-American pitcher, he thought it was a joke. Veeck told him that he wanted him to stand in the batter’s box and take some swings against him. Boudreau was competing with Ted Williams for that year’s batting title — he was an extraordinary hitter. He stood in and took about 30 pitches from Satchel, and he didn’t come close to getting a hit off him. At the end of that little tryout, the only thing he said to Veeck was, “Sign him, Bill.” So the next day, July 7, 1948, on Satchel’s 42nd birthday, he was signed to his first major league contract, and he never let Veeck down. He never let any owner who had faith in him down. He went on to a 6 – 1 record that season, had the league’s second lowest earned run average, and, most impressively for me, when the Associated Press writers voted for Rookie of the Year, Paige garnered 12 votes, which he was quite delighted by, but he said that he “wasn’t sure what year the gentlemen had in mind.”

PH Veeck liked Satchel so much that he brought him back with the St. Louis Browns in the early 1950’s, where he pitched pretty well for a time.

LT Yes, he pitched well for a while. Veeck always had faith in him, and Satchel never let him down. Satchel also grew really close to his teammates while with St. Louis. Veeck came to Satchel’s rescue three different times. The first, as we talked about, was in Cleveland, the second was in St. Louis, and the third was in the late 1950’s, when Veeck was involved with the management of the Miami Marlins, which at the time was a minor league club. Each time Satchel came back at a later age, each time he defied Mother Nature and logic and pitched well, and each time he stayed only as long as Veeck stayed, and was then let go.

PH Another baseball person that enjoyed putting his finger in the eye of the baseball establishment, Charlie Finley, brought Satchel Paige back at the age of 59 in Kansas City

BS That was extraordinary. Finley owned the Kansas City A’s, who were having a very difficult time bringing fans to the ballpark. In September, as the season was winding down, Finley realized that he could fill up the stadium for one night if he brought the ancient Satchel Paige in to pitch. So, he offered him a tidy sum of money, which Satchel could use, and brought him to the club with the intention of using him for three innings, not really caring how effective Satchel pitched. Finley set Satchel up near the bullpen in a big rocking chair that he brought in for the occasion, with a nurse in a white uniform next to him, rubbing something on his arm. He also had his own personal water boy. Finley was as good a choreographer as Veeck was, and it created this great scene. Then he brought in Satchel to pitch, and that night against the Boston Red Sox, Satchel pitched three shutout innings — the only guy to get a hit off of him was the young slugger Carl Yazstremski, who, after the game, gave Satchel an enormous bear hug. That bear hug was because a full generation before, Yaz’s dad had batted against Satchel in a semi-pro game on Long Island. Satchel was the only guy who stuck around long enough in baseball that he could face off against fathers and sons, and even grandsons. That night, at age 59 years, two months and eight days, Satchel set a record for being the oldest player ever in baseball, and it is a record that will never be broken. When we think of, in this era, Roger Clemens or John Smoltz coming back, in Clemens’ case at 45 and in Smoltz’s case 42, we think they are ancient. Satchel Paige came back and pitched three great innings at age 59, which has got to be a medical miracle.

PH Satchel is also remembered for his rules for staying young. Would you talk a little about those rules, and how they were spun out over the years?

LT Sure. Depending on when he told the story, there were five or six rules for staying young, and they involved everything from not eating fried foods, to not going out and wildly partying. All of these wonderful rules were interesting, especially so since they contradicted the way he lived. His most famous rule, and the one that made it into Bartlett’s Book of Famous Quotations was, “Don’t look back. Something may be gaining on you.” I think what he meant was that he was living in a world of fierce segregation, where it was very difficult for a black man like him to make a living — not to mention staying alive — and rather than looking at his situation as being tragic, he was perpetually looking ahead. His rules really reflected his wishes for how he would live if not always his ability to live up to them. The provenance for the rules is really quite interesting. They are all things that he might have said, some of them are things that he did say, and some of them are things that a reporter for Collier’s magazine may have heard Satchel say, or may have made up himself. It is clear that Satchel liked the way the reporter wrote up his rules for the magazine story since he adopted them as his forever.

PH But, as you mentioned, his behavior contradicted his rules. For example, he talked about fried foods, saying that they tend to “angry up your stomach,” yet he was quite fond of fried foods.

LT He loved them, and he knew he shouldn’t eat them. He also knew that he shouldn’t drink, and that he shouldn’t smoke, but he did both. In part I respect what he did with his rules because he was trying to set an example for his kids and for other kids, but he didn’t feel that he needed to live up to that example.

PH He was married three times. The first time to Janet Howard, a waitress at the Crawford Grill; the second marriage was in Puerto Rico to Lucy Figueroa, although he disputed its validity; and finally, later in life, he married Lahoma Brown. Satchel Paige seemed to be ahead of the curve as a modern athlete in his playboy role

LT He was indeed. He was ahead of the curve in loads of ways, starting off with the fact that he was a free agent well before we ever had anything like free agency. He was making and breaking contracts when it suited him, and when he could get more money. He was also out there doing some outrageous things in terms of his personal behavior. Yet he was a guy who had grown up in Jim Crow America, where rules were so carefully proscribed about what you can do, and more importantly, what you can’t do, and I think he decided, when he became a big enough star, that instead of listening to society’s rules, he was going to do what he wanted to do. If that meant at times he would have two wives, or carousing, or breaking contracts, he was going to do that. Society had made him live according to some tough standards, and when he became a big enough deal, he chose to live by his own standards.

PH He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971, and Ted Williams deserves some of the credit for this. When he was inducted in 1966, Williams acknowledged some of the Negro League greats and said that they are worthy of induction into the Hall of Fame. And of course, since Satchel’s induction, plenty of other Negro Leaguers, Cool Papa Bell and Josh Gibson among them, have been inducted. But the last years of his life — following his induction — were not good years…

LT Satchel lived his whole life according to his theory of not looking back, but when he got emphysema, and when he was confined to a wheel chair at the end of his life, he did more looking back in the way lots of older people do. And, when he did look back, for the first time in his life he started talking about some of the bad things that happened to him, and thought that people were forgetting about him. This made him very sad. Satchel Paige died in 1982, and I like to remember him for the first 75 years of his life, and not for the last year, when he grew to be a bit embittered. He was enough of a credit to the sport of baseball and to the American way of life that we owe it to him to cut him some slack. He was a man who didn’t start to have kids until his 40’s — he had seven of them — and continued to pitch into his 60’s so he could support these kids, because the only way he knew how to make a living was to pitch. It looked like he would pitch forever. He was an extraordinary guy whose second memoir was titled “Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever,” and, he really almost did.

____________________

“Ain’t no man can avoid being born average, but there ain’t no man got to be common.”

– Satchel Paige

Satchel:

The Life and Times of an American Legend

by

Larry Tye

*

About Larry Tye

Larry Tye was a prize-winning journalist at The Boston Globe and a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University. An avid baseball fan, Tye now runs a Boston-based training program for medical journalists. He is the author of The Father of Spin, Home Lands, and Rising From the Rails and co-author, with Kitty Dukakis, of Shock. He lives in Lexington, Massachusetts.

*

Larry Tye talks more about Satchel Paige

Larry Tye products at Amazon.com

Satchel Paige products at Amazon.com

*

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Neil Lanctot, author of Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution.

_______________________________

This interview took place on August 25, 2009

_______________________________

Other Jerry Jazz Musician interviews

# Text from publisher.