Intense, powerful, and compelling, Matterhorn is an epic war novel in the tradition of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’s The Thin Red Line. It is the timeless story of a young Marine lieutenant, Waino Mellas, and his comrades in Bravo Company, who are dropped into the mountain jungle of Vietnam as boys and forced to fight their way into manhood. Standing in their way are not merely the North Vietnamese but also monsoon rain and mud, leeches and tigers, disease and malnutrition. Almost as daunting, it turns out, are the obstacles they discover between each other: racial tension, competing ambitions, and duplicitous superior officers. But when the company finds itself surrounded and outnumbered by a massive enemy regiment, the Marines are thrust into the raw and all-consuming terror of combat. The experience will change them forever.

Written over the course of thirty years by a highly decorated Vietnam veteran, Matterhorn is a visceral and spellbinding novel about what it is like to be a young man at war: the anxiety and anticipation before the first encounter with the enemy; the fear and exhilaration and brutality of fighting; the tedium and relief of downtime; and, finally, the bonds between men, and the agony and despair of losing one’s friends. It is an unforgettable novel that transforms the tragedy of Vietnam into a powerful and universal story of courage, camaraderie, and sacrifice: a parable not only of the war in Vietnam but of all war, and a testament to the redemptive power of literature.#

Written over the course of thirty years by a highly decorated Vietnam veteran, Matterhorn is a visceral and spellbinding novel about what it is like to be a young man at war: the anxiety and anticipation before the first encounter with the enemy; the fear and exhilaration and brutality of fighting; the tedium and relief of downtime; and, finally, the bonds between men, and the agony and despair of losing one’s friends. It is an unforgettable novel that transforms the tragedy of Vietnam into a powerful and universal story of courage, camaraderie, and sacrifice: a parable not only of the war in Vietnam but of all war, and a testament to the redemptive power of literature.#

In an April, 2011 interview with Jerry Jazz Musician publisher Joe Maita, Marlantes discusses his book, his experience writing it, and his life of recovery following his return home.

*

Karl Marlantes, receiving the Bronze Star

_____

The rest of the day Mellas raged inwardly against the colonel. This gave him energy to keep moving, keep checking on the platoon, keep the kids moving. But just below the grim tranquility he had learned to display, he cursed with boiling intensity the ambitious men who used him and his troops to further their careers. He cursed the air wing for not trying to get choppers in through the clouds. He cursed the diplomats arguing about round and square tables. He cursed the South Vietnamese making money off the black market. He cursed the people back home gorging themselves in front of their televisions. Then he cursed God. Then there was no one else to blame and he cursed himself for thinking God would give a shit.

– An excerpt from Matterhorn

________________________

JJM I’ve spent a lot of time on the Internet reading comments from readers about your book, and many of them were from Vietnam War veterans themselves. In fact, the page for Matterhorn book reviews on Amazon is, I think, an amazing sociological forum that I encourage everybody to visit. In addition to the book reviews, people recount their own experiences in Vietnam and on the home front as well.

KM Yes, I’m a bit of a coward and somewhat introverted, and if somebody gives me a bad review, I get wounded. So my wife says, “I’ll read them first and if there’s a five star review, I’ll read it to you and if it’s a bad one, I won’t even tell you about it.”

JJM I understand your concern, but you don’t have much to worry about there. A common theme among the veterans is that they praise the novel’s authenticity, and ordinary citizens express gratitude that you wrote it. For example, one non-veteran wrote, “Thank you Mr. Marlantes for such a great story. My deepest respect to all of those who fought in the Vietnam War.” You must be incredibly proud of your achievement.

KM Yes, I do feel good. Veterans tell me that I “nailed it,” and that is very important to me it is worth 100 good reviews. It’s important because to a large extent I was just trying to tell our story. I mean, we were so badly received when we came home from Vietnam we couldn’t even get a date north of the Mason-Dixon line. I was stationed in Washington, D.C. after I came back, and there were signs in restaurants that said “No servicemen allowed” and this was in our nation’s capital!

I am always careful to say that the bad things that happened to veterans were because of the radical peace protestors who were a minority, but they were a significant minority. Most of them were honorable and not all of them spit on the troops and blamed them for the war, but I did experience a lot of hatred. One image that has stuck in my mind occurred after having been back from the war for a couple of months, and I had to take some papers to the White House while dressed in full uniform. Across the street a group of young students, probably about my age, were waving Vietcong flags while shouting obscenities and flipping the bird at me. I remember being stunned! I wasn’t angry, but I was hurt, and I remember thinking to myself, “You don’t know who I am. You’re just doing this to a uniform, and because I’m in a uniform, I can’t behave badly and go over there and shout back at you.” They were just so…hateful. I thought if I could walk across the street and explain to them that the people they called “baby killers” are three years younger than they were, and it’s only because they got to go to college that prevented them from serving in Vietnam. I wanted to explain who we were. So, in a way, Matterhorn was a way to tell a story of what it was like to be 19-years-old during that time period, growing up in a war and dealing with all the things we had to. This was an experience that a lot of kids went through.

JJM You had dual traumas fighting in the war, and coming home to that kind of reception…

KM It’s even got a name; the “Safe Harbor Trauma.” You think that you are finally safe because you are coming home to the loving reception of your grateful country, but, it wasn’t the case. It was so bizarre. They told us things like we should take our uniforms off so that we wouldn’t disturb people in the airports. If we flew standby because it was half price if we were in uniform they said we should fly between midnight and three-o’clock in the morning so there wouldn’t be any trouble. My reaction was, “Wow! This is what we came home to?” Today I see beer commercials where people are clapping as the troops get off the airplane, and see how drastically things have changed.

JJM I lived in the San Francisco Bay area for much of the war in Vietnam specifically Berkeley, which was the epicenter of war protest and I was one of those guys with an attitude about the military. The soldiers were a symbol of some of the bad choices our country made, and targets of a very unpopular war.

KM Yes, we were easy targets and most of the protesters were young. When you’re young, you’re black-and-white and you’re stupid. I look back on it now and see that America was just going crazy at the time, and the way we were treated upon our return was a part of the craziness.

JJM It’s one thing to write a war novel based on your experience. It’s another to write what many are calling a “literary classic.” What writing experience did you have prior to writing this book?

KM I started writing when I was about eight or nine. I had a little diary that I kept and I would write my dreams down in it. I eventually burned it. A little bit later, my cousin and I decided to write a novel about two nine-year-old boys saving the world from space invaders. It was about 12 pages long and has since been long lost. Then, while in high school in Seaside, Oregon, I was reading Kierkegaard and I wrote a black mass from the viewpoint of being thankful for all of the bad things that God has done to the world. My father found it and he was outraged it was my first major lecture on blasphemy. So, he made me go out in the backyard and burn it.

JJM Did you feel like you had to hide your writing after that?

KM No, not really I put that in perspective. I mean, it’s my dad. But when I was at Yale, I won the Tunic Prize for Literature, which is a short story contest. So, by the time I got back from Oxford, I figured I could write the “Great American Novel” about the war. So, I’ve always been a writer…

JJM Did you read a war novel before going to Vietnam?

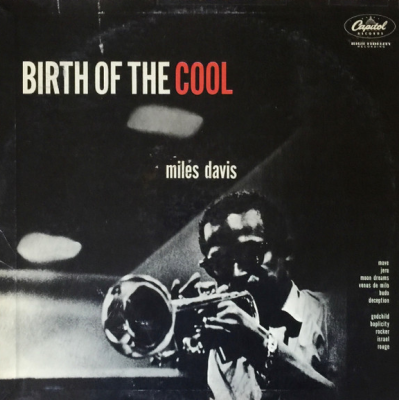

KM Oh, yes. I read The Naked and the Dead and The Thin Red Line before I went to Vietnam. When I found out I was going to Vietnam, I started getting into World War I poets in fact, a girlfriend of mine gave me a book of Wilfred Owen poems that I carried with me for a long time in Vietnam. These World War I poets nailed the mechanized horror of modern war.

If you read Horatio Hornblower you learned that if you were fast on your feet, smart, good with a sword, and were daring and dashing, you could shave the odds all of these things would help you live. But by the time World War I came around, I don’t care if you went to Oxford and were the fastest runner in the world, if the shell hit your hole, you were dead there was nothing you could do about it. Death became much more random and you were so much more helpless than back in the day of pre-American Civil War. So, these poets were important to me.

I tried reading Tolstoy when I was high school, but I was too young to appreciate him. When I came back from Vietnam, I couldn’t put him down. I think I stayed up all night and day for three days reading War and Peace and I was like, “Oh my God!” In my opinion he is still the “great novelist.” He handles characters so well. The war novel is complex, and one of the major issues I faced artistically was how to show how the protagonist is completely in over his head and confused, and because there are so many new faces and names in the book, how do I get all of this across without making the reader feel so confused that they throw the book down? So, when I started writing my book, I went back and I reread Tolstoy and saw how something like stuttering could identify a character. So, in my book the character Jacobs stutters because it is a way to identify him, and you could remember other characters if one of them has a tic, or if someone has an odd way of looking at you while he’s talking to you.

JJM So, you started writing this book over 30 years ago, but it wasn’t until 2010 before it was published. When did publishers begin taking your manuscript seriously?

KM They never did. It’s really interesting, but a mistake was made in the telling of this story, and it made its way to the Internet, and you can’t ever correct that. When I first came back from Vietnam in the summer of 1971, I was at Oxford, and during an eight week summer vacation, I maniacally typed out 1,784 pages on an Adler typewriter. I remember telling somebody that it was “probably about 1,600 American pages,” and while I thought I was writing a novel, I now understand that it was actually a first-person psycho-dump, and a month after writing it I re-read it and I was not happy I devoted four pages, for example, to the fact that I had wet socks and couldn’t get dry ones. I realize now, of course, that what I was doing is what is now called “journaling,” but the important thing is that I just had to get it all out.

So, when I told somebody that, the rumor became that Matterhorn‘s first draft was 1,600 pages long. There was a lot having to do with Matterhorn within those 1,600 pages because many of the things that I was writing about happened to me, so this was about me getting stuff out of my system.

Then, in about 1975, I started getting serious, and began reading books about things like how to structure a plot, and how to develop character arcs. I started reading those things and realizing that there is actually craft to this art form! So, the first draft came out in 1977, although it was clearly still too big it was about 1,100 or 1,200 pages, double-spaced and typewritten. I started writing query letters and, at best, I’d get somebody to say, “Send me a page or two,” but no one picked up the manuscript. I was told that I was an unknown writer, that it’s a big book, and that since it’s about Vietnam, which no one wanted to read anything about, there was no market for the book. And these are things I heard from those who were kind enough to send me some sort of answer to my query letters. So, I gave up. By that time, I had a couple kids, and Mario Puzo had it right when he said that you can’t make a living writing fiction in America, but you can make a killing.

JJM Oh, that’s right…

KM So I made another run at it in the 1980’s, and those who answered my query letters would tell me that there wasn’t a market for it, that Hollywood has done Vietnam, and it’s over. There was Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, Apocalypse Now, Deer Hunter, and the market is done. In the mid-1990’s, I got people writing me back and they would make suggestions like, maybe they could do something with your book, but, since the Gulf War had just happened, could I just change it to the Gulf War? Now I tell people, a little tongue-in-cheek, that I’m so thankful that by that time Microsoft had come up with search and replace because I could just put replace the word “jungle” with “desert!” And, since I had a mountain in my story, maybe I could make the story be about a mountain in Afghanistan and we could sell that.

Literature is a difficult marriage between art and commerce because you don’t get your art our there unless people who are in business can make a profit on it. I don’t complain about that, that’s just the way it is. Even Michelangelo had to find patrons. It has always been this way, and it is certainly that way in this country with the New York publishers.

JJM Well, it could also be that the pain of Vietnam has affected us for so long that it took until recently before we were ready for a book like Matterhorn.

KM Well, yes. I like to say that it’s like having the alcoholic father. It’s the family secret. Everybody tiptoes around it. We all know Dad drinks too much, but nobody talks about it, and Vietnam has been like that for decades. It’s influenced everything in our foreign policy, our political parties, and even who’s in our political parties. It has been an amazing factor in our current situation in Afghanistan, which is so eerily parallel to Vietnam that it blows my mind.

JJM When people described Vietnam when the war was being fought, the word frequently used was “quagmire,” and Matterhorn the mountain where much of your book takes place is a great symbol of a quagmire…

KM Yes, this mountain was a conscious symbol of our “doing it to ourselves.” I mean, in Vietnam, we “did it to ourselves.” So, in Matterhorn we build it, we leave it, we go back after it at great costs, and then we leave it. It is the central symbol of the novel.

JJM In The Good War, Studs Terkel’s great oral history of World War II, he quoted a veteran of that war by the name of John Charte, who said this about Vietnam: “I feel sorry for the kids in Vietnam. They couldn’t have figured out what it was they were fighting for. I knew why I was there. That doesn’t mean I wasn’t scared. I don’t know what I would have done in Vietnam. I mean, I’m a botch as a killer, as a soldier, but as an American, I felt very strongly I did not want to be alive to see the Japanese impose surrender terms.” So, World War II had a goal getting to Tokyo…

KM Absolutely. Vietnam was the first war that I know of where there was no clear cut way of knowing whether we were winning or not. During World War II, there was Guadalcanal got it; Tarawa got it; the Mariana’s yep, we’re getting closer. Then the Philippines, Okinawa, and Tokyo’s next! You could measure progress, and on the European front as well.

The other thing is that I talked to my dad and my uncles and their friends who were in the second world war, and when they were in combat, they said that beating fascism for democracy was not a motivating factor what motivated them was saving their friends and saving their own skins, and in getting the job done. This is like it always is in war. But, the difference is that there were actually good guys and bad guys. Today, I think you can stand up and say that the world is better off because fascism and Japan were defeated. We didn’t want to have the Japanese impose surrender terms on us. So, when they came home and had to deal with the fact that they had killed 19-year old Germans who were just fighting for the Fatherland they weren’t Nazi’s they could at least say that it was done in good cause, and that we contributed to the good. In Vietnam, you couldn’t. I wrote a scene in my book where one of the characters gets angry at the lieutenant and starts crying out “Where’s the gold? Where’s the gold? If someone would just tell me there’s gold or oil or something here…If I knew why I was here I would feel better.”

JJM Vietnam was a war of body counts, and interpretation of the war’s success and failure on the battlefield was really determined by the numbers of Vietcong killed each day…

KM Yes, and there were other metrics as well, like the number of villages pacified, but how in the hell would they ever know what a pacified village was, because it could be that everyone was smiling and happily selling trinkets to the American soldiers in the daytime and then they go out at night and set up land mines. I make fun of this in the novel, when Mellas has to call in a body count and by the time it gets to Saigon, it is considered a major victory.

Body count became a measure that people actually got promoted on because it was the only way that you could determine whether or not we were making progress. If you took the hill in World War II, it was great because they were one step closer to their goal…

JJM And it wasn’t surrendered back to the enemy after it was taken…

KM Absolutely, you don’t leave it. Try and tell troops that we just had 19 dead taking this hill I had that happen to me, and it happened to so many Vietnam veterans. I’ve had them come up to me in book readings and say, “I know what hill that is. That’s 881 South,” or “That’s hill 55,” and I’ll tell them that it wasn’t, but, while I made the hill up, it was any hill you fought on.

The other thing about body count that I think is so bad is that it is immoral. I mean, the military is not there to kill people. The military is there to use violence and the threat of violence to get another side to stop killing your people. While you have to kill them to get them to stop, but, as soon as they stop, you’re done. You’re not there to kill people. You’re there to get the killing stopped if you’re doing it from the right perspective. So, it’s immoral. The other one is that American people only care about one side of that ratio. You could say we killed 600 NVA today and lost four Americans. but the headline will read, Four Americans Killed in Vietnam.” So, it’s a stupid political thing as well.

JJM You’ve told other interviewers that you’re not like Waino Mellas since you don’t possess his ambition or political skills, but did you experience what Mellas experienced?

KM Oh, yes.

JJM So that character is you, basically…

KM That’s authentic, yes. There are scenes that I didn’t experience for example, I had a close friend who was in a company that lost a guy to a tiger but it was my company that had to go out to find the body.

JJM God…

KM Yes, try sending a half-eaten body home to mom and dad that’s kind of interesting. The nurses’ scene is in there because the subtext of the whole novel is the Parsifal myth and I needed these feminine figures for Mellas to incorporate and deal with. While I was mooning over all the nurses, they wouldn’t talk to me! But yes, the final assault I describe at the end came from my experiences on a hill called 484.

JJM When did the magnitude of all your war experiences hit you?

KM It started unconsciously. I remember that very early after the war it was probably 1970 every once in a while I would run into someone I fought with over there, and we would ask each other, “What’s this thing I hear about veterans having nightmares? Do you get nightmares?” And neither of us would admit to having them and we figured it was bullshit.

Then, about 1985, I was in a very tense meeting. I was in the strategy business, and strategy involves major changes in direction, which involves vice-presidents getting more people or losing people, so, these meetings are emotionally heavy so heavy that a guy died of a heart attack during one of them. After that day, my heart started pounding so hard I could hardly breathe, and I thought this was triggered by that heart attack, but I didn’t have a clue what it was. But, it was actually so common among Civil War veterans that they even came up with a name for it it is called “Soldier’s Heart.” It is basically adrenaline.

I went to the doctor and was told that there was nothing wrong with me, that what I was experiencing was just a little stress that a little rest would help. By the late 1980’s, I would wake up in the middle of the night and was sure I was going to die. I actually wrote a letter to my family one night because I didn’t think I was going to live beyond another hour. So, I wanted to say how much I loved them and I wrote them all a letter and said good-bye, but the sun came up and I was still there! Well, I was told that was called a panic attack, which I had never heard of before.

Finally, at the end of the 1980’s, it all started unraveling. I was running a corporation in Singapore at the time, and I walked into the board room just before a big meeting and on the table was a pile of dead Marines. I mean, I knew they weren’t there it wasn’t a flashback, and I wasn’t psychotic, it was an intrusive thought that can’t be stopped. And, we know about “triggers” now, and there were so many triggers there moist air, jungle, East Asian people. So, I’m supposed to be conducting a board meeting and there’s this pile of dead bodies, and I get outside to remind myself that they are not there, but, I don’t know what is going on. I had to gin it up and put a nice smile on my face and power through the meeting. After that point I would have an overwhelming urge to start crying while talking to people. I thought this was because the job was really stressful, and that I wasn’t cut out to be a CEO. I would get into elevators and, after the doors would shut, burst into tears and sob, and by the time I’d get to my floor I had to get it together and step into the hallway people would wonder why there were tears in my eyes, and I would smile and try to move on. I basically cracked up. I had to quit the job and came back to America, and that was when my marriage really started to fall apart. So, it was a tough time. I had never heard of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

JJM Were there any PTSD treatments available to you upon your return?

KM When I got back, I didn’t know about any, but they had just started. I think the VA actually was going through policy fights about PTSD around that time the late 1980’s and early 1990’s.

In the mid-1990’s I lived in a little town called Los Olivos, which is north of Santa Barbara, and I was doing stuff that made my wife think I had gone completely nuts. One day, I was in my car with my three-year-old daughter, and, because I was a little slow off-the-mark leaving an intersection, the driver behind me blasted his horn at me to move. By the time I became conscious again of what I was doing, I was on the hood of his car trying to kick his windshield in and I’m saying to myself, “Well, this is a little embarrassing.” On another occasion, there was a sudden noise that sounded as if it were right outside my house, and I got out of bed and ran stark-naked out into the street, trying to find who was there so I could get him…so I could protect the house.

My wife thought that this was about job stress, so she encouraged me to go to a workshop at the local school where therapists from the county would be, and I could talk to them about my job stress issue. There were 70 or 80 people in the school cafeteria and, when it was my turn, I started telling him those stories and he asked me if I ever fought in a war. Well, the floodgates opened, and I burst out bawling. I mean, I couldn’t stop crying. I cried so much that my ribs hurt for two or three days after that. I don’t know how long I cried it could have been 15 minutes but everyone in the cafeteria was looking at this guy falling apart at his table, and the therapist tells me that I have something called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and asks if I had ever heard of it. I tell him I hadn’t, and he takes out his card and writes, “Larry Decker: Department of Veterans Administration” on the back of it and tells me that wants me to go this man…now! Not tomorrow. He made me promise him that I would go see him, and, that is how I started getting treatment. That was about 1995 or 1996. Decker clearly knew what a major issue post-traumatic stress is, and was working very hard with it.

JJM In a book called War and the Soul: Healing our Nation’s Veterans from Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, the author, Edward Tick, writes “The Odyssey recounts Odysseus’s adventures on the way home from war, and has served as the model of the hero’s journey and the warrior’s return ever since. Along the way, Odysseus had to survive many ordeals. Every soldier is Odysseus, in that the soldier’s journey home from war is always long and complicated; his body often arrives long before his mind adjusts.” I think that is something we may just now be understanding…

KM Well, yes, and the problem is even deeper than that. The mind cannot readjust all you can do is have the mind learn how to cope with its new way of being. A way to explain this is to say that everyone is familiar with the statistic showing that if you are going to be wounded or killed, it is much more likely to happen during the first couple of months in combat rather than later. The reason for that is because when you are in a normal state of mind, you may hear a noise, for example, and it goes through your cortex and you’re thinking, “Gee, I wonder what that noise is. Is that the wind? Or, maybe it’s a little animal, or maybe a branch fell down or, heaven forbid, maybe it’s the North Vietnamese Army?” Well, by the time you’ve gone through all that, you’re dead.

What happens under extreme adrenaline loads is that the mind reorganizes. You hear the sound and it skips the cortex and goes directly to the amygdala. The result is, you respond to the noise by turning around and shooting it. You’re not even thinking anymore. It’s just fight, fly, freeze and sound full automatic. Once that’s changed in your brain, you can’t get it back. But, what you can do when you hear a sound now, or when someone honks his horn at you, is what the VA teaches, and that is to count down: “Ten, nine, eight. Take a deep breath. Seven, six, five. He’s just an asshole, he’s not trying to kill you. Four, three, two, one and…I’m trembling and my heart’s racing, but I’m not being crazy anymore.” Then they give you medicine and that helps. This is an actual restructuring of the brain. There’s no going back, but you can get help and you can learn. What happens instead is that people try to numb that sort of thing by using alcohol and drugs. Nobody understood any of this after Vietnam brain science wasn’t there yet. We couldn’t measure neural pathways in the 1980’s and 1990’s, but we can today.

JJM Racism is a paramount theme of your book. It struck me how in only 20 years’ time, we went from a country who generally wouldn’t allow African-Americans on the battlefields of World War II, yet in Vietnam they made up a large number of the fighting units and this was happening simultaneous to all the events of the civil rights movement. Did the African-American soldiers you served with express this hypocrisy to you?

KM Oh, absolutely.

JJM How so?

KM Well, I was well-liked, so they talked to me. They’d say something like, “What the fuck’s going on, Lieutenant? We’re over here with this war and I don’t even know why we’re here. I go back home to Mississippi and I can’t even pee in the same place as you do.” So, yes, they would express it openly. That started during World War II because black units were fighting, but they were segregated.

That was when this irony started to really hit them. In 1948, President Truman integrated the military, and I often tell people that while the schools got the major press in the civil rights movement for integration because that is where the reporters were, imagine integrating a school where every student in the school is armed with an automatic weapon and has hand grenades! Now, that’s racial tension, and that’s what the military faced. We had armed 19-year-olds with 30 times the testosterone going through their systems than they will at any other time in their life, and they were angry because they could see what was happening around the country. Watts was going up in smoke, and so was Newark and Detroit, and Martin Luther King was assassinated. These kids weren’t dumb they knew what was going on. This was during a time when people were seriously worried that Huey Newton and the Black Panthers were going to start a civil war and I’m not talking about some kind of violence in Watts, I’m talking about actual guerilla warfare and the whole country going up in flames because they were arming. It was a very scary time.

Malcolm X was saying at the time that there is no way we can integrate the races, that we have to separate, which brought up the thought of having black states and white states. Regarding King’s assassination, it was the black community that put the lid on the anger. They said it was a crazy man that killed him, not white people. And most of the black kids in Vietnam said their being there was terrible and unfair, but they did their job. When you’re out in the bush, there’s no color out there. That was one of the things that was so tragic. Guys would be tight. They’d know that this black kid or this white kid had their back on a listening post. If they said they’d get the fire team there at 0800 on the left flank, they’d be there. They understood that they could trust each other and they didn’t need to be afraid of each other, but if you go back to the rear area and in 1968 this was in the book everybody had to split up because you didn’t want to be caught with the wrong race if the shit goes down.

But, I give the military enormous credit for integration in this country. It was not fun and it was not easy, but it’s where it happened, and it happened in Vietnam. I talk to guys who are in the Marines today and they say, “You had racial problems? Really?” It surprises them. Thank God we made some progress.

JJM Well, it’s sort of a microcosm of our whole society…

KM Of course it is…

JJM We have an African American president now, and our society today is so multi-racial compared to the days of World War II…

KM That’s right, and, I have to laugh when I tell this now, but, growing up in Oregon I wasn’t exposed to Mexican food until Ray Delgado, a kid of Mexican heritage from Texas, had a tamale sent to him in Vietnam by his mother. I asked him what it was and he let me have one. That was how separated we were culturally at the time.

JJM Separated musically as well?

KM Yes, even the music in Vietnam was segregated. You had those who listened to soul music and then you had country/western music and then you had the Beatles and the Rolling Stones rock music. All of those songs were very important to us, especially, “We’ve Gotta Get Outta This Place,” that’s the theme song.

JJM Do you ever wonder, Karl, why you have had to carry such a heavy burden in your life?

KM Yes. I have asked that it is one of those deep existential, religious questions why do some people suffer more than others? When I compare my life to being an abused child, hell, Vietnam pales. If you get right down to it, it is ultimately about soul. A woman who makes chapatti in India is not going to work for Goldman Sachs why is she there, and why is a woman who grows up in an upper crest family in New York going to end up working for Goldman Sachs? What’s fair about that?

The only way I can answer that is that life isn’t about how much money you make, or what your career is it is about your soul development. For some reason, there was a group of us who had to fight a war that was unpopular, and those of us lucky enough to return had to come back and try to get some consciousness about what was going on there. I wish I could remember who told me this originally, but the German philosopher Jurgen Habermas said that there is no greater opportunity for learning than to be on the losing side. He was of course talking about Germany but, because we were the knight in shining armor after World War II, we didn’t get conscious about how horrible war is because we were striking blows for freedom and justice, right? Well, that’s dangerous inflation. On the other hand, when you lose, you ask, “Now what?” You actually get reflective about it. I’m not a pacifist, believe me. I mean, I think we should have gotten Osama bin Laden and we should have been looking for him instead of getting caught up in this…quagmire. So, when I think about what my role was being over there, I believe that it has made our culture more conscious. A group of us went through this pretty horrible time and we’re trying to bring it to consciousness.

There was this wonderful reading I did in Berkeley, at an independent bookstore called Mrs. Dalloway’s. Before the reading I called my publicist and told her, “You’re not sending me to Berkeley! I’m not going to go there. Are you kidding me? I’ll have people with signs outside and it’ll be a scene.” She said, “I don’t think so.” She called up the store owner who said, “No, it’s going to be okay. We won’t have problems. I assure you.”

I went down there and that room was filled, and 99% of them were ex-war protesters. I mean, there were people out in the street. So, I’m thinking that this is going to be pretty interesting. I read a couple of passages from the book and then take questions. Very quickly, they weren’t even talking to me anymore; they were talking to each other across the room, telling stories about what they were doing in Berkeley during the war, questioning one another about their behavior, and how they could blame the troops for the war. Others said they didn’t blame the troops. It went back and forth like this through the whole room they were trying to sort out the 1960’s, and I was up there at the podium, just watching it. It was a wonderful feeling. Here was this group of aging baby boomers asking themselves, “What the fuck happened?” and I thought it was very healthy. I thought, “This is literature. This is great!”

JJM Obviously, the people who were old enough to fight in Vietnam but remained stateside experienced a completely different sort of trauma than the soldiers did, but I do believe that many of us probably including the anti-war demonstrators you encountered in Berkeley are dealing with the guilt of how we treated the soldiers returning from Vietnam. So, those of us who are old enough are still fighting that fucking war in some form, even today…

KM Absolutely. My own brother got out of going to Vietnam because he was an all-state football player. He went down to the draft board and told the chairman of the board that he was going to play for Tommy Prothro at Oregon State, so don’t send me over there to be killed. The draft board said not to worry, and they took care of it. So, that was sort of unfair. Now, friends of mine who didn’t go will often say to me that at times they look back and wonder if they should have gone, but, on the other hand it was a fucked-up war so maybe I shouldn’t have gone. So, there is this back and forth. Veterans have guilt I mean, we killed people and people who were on the opposite side of the fence also have guilt. Welcome to the human race. It is only from talking about it and learning from it is how we make progress.

JJM That war has been embedded in the psyche of the baby boomer generation, and I think that in addition to it being great literature, Matterhorn will help bring clarity and intelligence and passion to future generations who study Vietnam.

KM Yes, and every once in a while my ego gets in there and I say to myself, “Hey, maybe they’ll be reading Matterhorn 50 years from in a high school some place.”

JJM How has the military reacted to the book?

KM I was worried about how the current military would react to my book especially the Marines, because I am a Marine but they have embraced it.

I was at the Naval Academy recently, talking to the Midshipmen, and talking about the lessons of the book in terms of the moral dilemmas faced by Mellas. A month before that the commandant of West Point called and asked me to talk to the cadets it turns out they are actually using the book in their leadership classes. The Marines just gave me the James Webb fiction prize from the Marine Corps Heritage Association, and I have had generals tell me they want every officer in the Marine Corps to read this book. And…I didn’t pull any punches!

______________________

Mellas tried to shake off the other images, the burned bodies, the smell, the stiff awkwardness beneath the wet ponchos. He couldn’t. The chanting went on, the musicians giving in to the rhythm of their own being, finding healing in touching that rhythm, and healing in chanting about death, the only real god they knew.

Mellas didn’t sleep that night. He sat on the ground and stared out to the northwest, toward Matterhorn. He watched the mountains subtly change under the shadows of clouds cast by a waning moon as it moved across the sky until the shadows began to fade with the coming of light in the east. He tried to determine if there was meaning in the fact that cloud shadows from moonlight could move across the mountains and yet nothing on the mountain would move or even be affected. He knew that all of them were shadows: the chanters, the dead, the living. All shadows, moving across this landscape of mountains and valleys, changing the pattern of things as they moved but leaving nothing changed when they left. Only the shadows themselves could change.

– An excerpt from Matterhorn

___________________

Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War

by

Karl Marlantes

*

About Karl Marlantes

A graduate of Yale University and a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, Karl Marlantes served as a Marine in Vietnam, where he was awarded the Navy Cross, the Bronze Star, two Navy Commendation Medals for valor, two Purple Hearts, and ten air medals. Matterhorn is his first novel. He lives in rural Washington State.

__________________________

JJM Who was your childhood hero?

KM The first person that comes to my mind is Captain Horatio Hornblower.

JJM Why him?

KM I was always very shy when I was a kid, and am still pretty introverted. So, here’s a guy who’s awkward and shy and yet he’s the bravest naval captain in the British Navy. It is the perfect seven or eight year old boy person to identify with. He’s always terribly concerned about his crew and fairness, and then he does all the brave deeds. At the same time, he’s bumbling around and can’t talk to any girls. So, he is who popped into my mind just now – assuming it’s fair to use a fictional character.

JJM Sure it is. Did you carry him with you on the battlefield?

KM Oh, that’s interesting. Of course! He is one of the great models of an ethical warrior, and my definition of an ethical warrior is one who is not out there just to slaughter people, he is trying to accomplish things for his crew and his country. He’s a leader. In an unconscious way, I think he probably was important to me on the battlefield. I haven’t thought of those novels for years, and your question got them to pop into my head.

*

Critical Acclaim for Matterhorn: A Novel of the Vietnam War

_____

“Matterhorn is a raw, brilliant account of war that may well serve as a final exorcism for one of the most painful passages in American history…It’s not a book so much as a deployment, and you will not return unaltered…One of the most profound and devastating novels ever to come out of Vietnam or any war.”

Sebastian Junger, The New York Times Book Review (front-page review)

*

“Few war novels give you life and death in the field this vividly…Matterhorn will take your heart and sometimes even your breath away.”

Alan Cheuse, NPR’s All Things Considered

*

“A powerhouse: tense, brutal, honest.”

Time

*

“Matterhorn is one of the most powerful and moving novels about combat, the Vietnam War, and war in general that I have ever read.”

Dan Rather

*

_______________________________

This interview took place on April 28, 2011

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview on Vietnam with David Maraniss, author of They Marched Into Sunlight

*

Natick Veterans Oral History Project personal recollections of war veterans

Returning Veterans Project free counseling services offered to returning veterans

_______________________________

# Text from publisher.

The novel, and the interview with the author rang, and ring true. I served in 2nd platoon, 1st Force Recon Co.,(1st Marine Division), 1969-70. I don’t know if it’s the same Marine the author is talking about, but a Sargent in my Company, Sgt. Phlegm, was killed by a tiger 1970). Semper Fi

Ironically coming across this interview on the 50th anniversary when our line company, Charlie Co., 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, first made contact with a North Vietnamese Army unit that we fought for the next 8 days.

Up until a few years ago, I have had the same recurring dreams about the battle. Especially when two Marines from the company that relieved us, Lima Co. 3/4, triggered a land mine that immediately killed three more Marines, well after our hill assault. I was but a few feet away and on an angle that where I avoided the killing radius of the blast.

This ‘lucky’ break filled me with such ‘survival guilt’ that I apparently subjected myself to an anniversary of periodic recurring dreams, depression, and intrusive thoughts that disrupted my sleep, concentration and, of course, peace of mind. In combination with my work related stress as a special education teacher, it led to three in-patient treatments at VA psychological programs, impacting my career, my relationships, and life. I’m happy and relieved to say I don’t have the nightmares anymore and a means to cope with the depression. Principally, I’ve forgiven myself for surviving while others did not. I’ve found grieving rituals to be important to recovery. I have two comrades buried nearby who lost their lives on that hill and I visit their graves around this time. I pray and I meditate on their sacrifice. Additionally, I ask those Vietnamese soldiers whose lives I took to forgive me. It seems to help. Semper Fi, Karl!