.

.

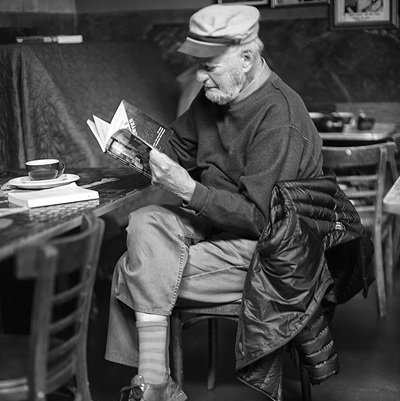

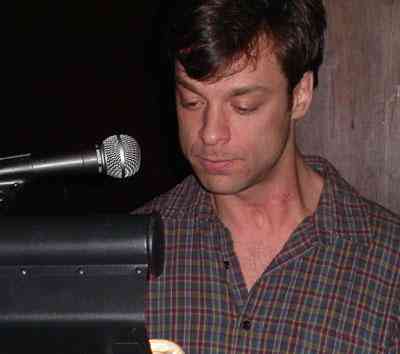

Joshua Prager,

author of

The Echoing Green:

The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World

.

____________

.

…..The 1951 regular season was as good as over. The Brooklyn Dodgers led the New York Giants by three runs with just three outs to go in their third and final playoff game. And not once in major league baseballs 278 preceding playoff and World Series games had a team overcome a three-run deficit in the ninth inning. But New York rallied, and at 3:58 p.m. on October 3, 1951, Bobby Thomson hit a home run off Ralph Branca. The Giants won the pennant.

…..Joshua Prager’s The Echoing Green follows the reverberations of that one moment the Shot Heard Round the World from the West Wing of the White House to the Sing Sing death house to the Polo Grounds clubhouse, where a home run forever turned hitter and pitcher into hero and goat.

…..Joshua Prager’s The Echoing Green follows the reverberations of that one moment the Shot Heard Round the World from the West Wing of the White House to the Sing Sing death house to the Polo Grounds clubhouse, where a home run forever turned hitter and pitcher into hero and goat.

…..It was also in that centerfield block of concrete that, after the home run, a Giant coach tucked away a Wollensak telescope. The spyglass would remain undiscovered until 2001, when, in the jubilee of that home run, Prager laid bare on the front page of the Wall Street Journal a Giant secret: from July 20, 1951, through the very day of that legendary game, the orange and black stole the finger signals of opposing catchers.

…..The Echoing Green places that revelation at the heart of a larger story, re-creating in extravagant detail the 1951 pennant race and illuminating as never before the impact of both a moment and a long-guarded secret on the lives of Bobby Thomson and Ralph Branca.#

…..In a November 24, 2006 interview, Prager discusses this revelation that Jerry Jazz Musician contributor Paul Hallaman accurately states “…undoubtedly comes as interesting news to many readers.”

.

.

__________

.

.

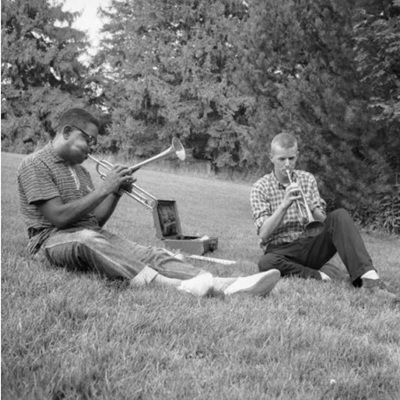

Photofile

The Giants celebrate at home plate following Bobby Thomson’s home run

.

*

.

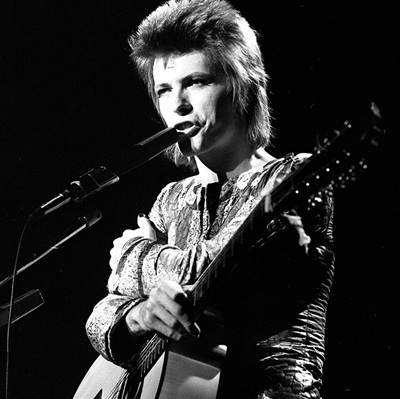

Seymour Waller, New York Daily News

Thomson acknowledging the crowd

.

*

.

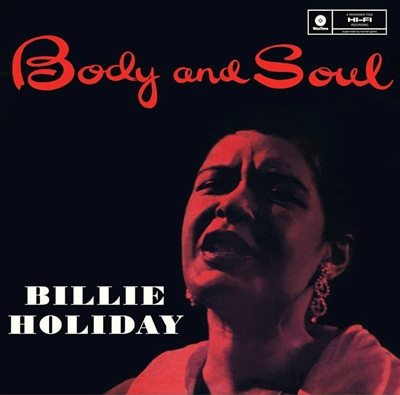

photo by Barney Stein

Ralph Branca crying in the clubhouse following the game (with Cookie Lavagetto at left)

.

*

.

“In the summer of 1951, authorities sought to bleach scandal from sport. Judge Saul Streit sentenced fourteen students at City College of New York, Long Island University and New York University for conspiring to fix basketball games. The United States Military Academy at West Point expelled ninety cadets, among them thirty-seven members of the football team, for cheating in its classrooms. And on July 19, the very day [Leo] Durocher exhorted his players to cheat afield, Pennsylvania governor John S. Fine signed into law Act No. 229. It stiffened the sentences for fixing athletic contests, for causing ‘to be lost any game or contest or match or race or sport,’ up to $10,000 and ten years in prison.

“None of that gave Durocher pause. Stealing signs was different.”

– Joshua Prager

.

_____

.

.

.

_____________

.

Bobby Thomson

*

1951 Statistics

Games: 148; At Bats: 518; Runs: 89; Hits: 152; 2B: 27; 3B: 8; HR: 32; RBI: 101; BA: .293

PH On August 11, 1951, the New York Giants were 13 ½ games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers in the National League standings, their season seemingly lost. However, a chain of events transpired that changed the course of the season, culminating in the Giants catching the Dodgers and forcing a three game playoff for the pennant. In your book, you point out that part of the Giants’ success late that season came as a result of a sign stealing scheme whose protagonists included their manager, Leo Durocher, a coach, Herman Franks, and others, including Sal Yvars and Hank Schenz. This undoubtedly comes as interesting news to many readers. How did you find out about this?

JP In the fall of 2000, the New York Mets and New York Yankees were positioned to meet in the World Series, and, as a features writer for the Wall Street Journal, I thought it would be interesting to write an article about Subway Series of the past, and along the way possibly find a story no one else knew about. So I contacted Barry Halper, who was a minority owner of the Yankees — who also happened to be the father of baseball memorabilia and collecting — and asked him if he knew of some interesting Subway Series anecdotes he could share with me. He started talking about a few things that happened during those years, and mentioned the rumors about the Giants stealing signs in 1951. I then asked him if he though they were true. He said no, he didn’t believe they were true for two reasons; one was because Ralph Branca — the man who threw the pitch to Bobby Thomson — was the one who told him, and the other was that Thomson’s home run was baseball’s most famous moment and any cheating would have been proven by now.

After I got off the phone with him, I thought that if I could prove that the sign stealing scheme did go on, it would be fascinating, not only because this is such a sacrosanct moment for so many people, but more so because I was interested in what it was like for these old ball players to have carried a secret all those years. I began by putting together a list of anyone who played for the Giants in 1951, as well as everyone who got paid World Series shares — which included the groundskeepers, clubhouse people, and anyone who had anything to do with the team. I went over the lists and found that 21 ballplayers were still alive at the time, as well as one coach, Herman Franks. Sadly, only 13 are alive today. As I contacted them individually, little by little I was able to pick up on the scheme and put the story together.

PH And what a story it is

JP Yes. On July 19, 1951, the Giants were 7 ½ games behind the Dodgers, and Durocher called a team meeting and told them that while it wasn’t likely they would win the pennant, they needed to improve their play. He also told the players that they were going to begin stealing opposing team’s signs, the hand signals between the catcher and pitcher that determine the kind of pitch being thrown. He told the team that their ballpark was perfectly laid out to steal the signs because the centerfield clubhouse where the players changed and held their meetings was directly aligned with home plate. There were 14 windows that ran along the base of the clubhouse. He told the players that behind one of them, he was going to station a spy who would view the catcher’s sign with a telescope. The spy would then press a button that, via a buzzer wire that ran from centerfield to the Giant bullpen in right centerfield, would inform a backup player in the bullpen of the pitch. He would in turn send a hand signal to the batter. The Polo Grounds was the only park in the league that had bullpens in fair territory, so all the batter had to do was peek towards right centerfield to get the sign. So, stealing the signs was this three part process — spying the sign, pressing the button, relaying the sign — and it began the very next day, July 20.

The Giants then went out on a very long road trip, during which they lost more ground to the Dodgers, and by the time they returned home on August 10, they were 12½ games behind. The men who were primarily involved in this scheme were Durocher, Herman Franks, who had been the third base coach, and an electrician named Abe Chadwick. People often wondered where Franks had disappeared to after July 20 — he was in the centerfield clubhouse, stealing the signs via a telescope provided by Hank Schenz. Sal Yvars, the backup catcher, received the signs in the bullpen and signaled them to the batter. My favorite story among these men was that of Abe Chadwick, the electrician who loved the Dodgers but who worked for the Giants.

PH He was fatally ill at this time, wasn’t he?

JP That’s right. He broke into the majors the very same day that Jackie Robinson did in 1947, and worked for the Giants from 1947 through 1951.

The backup catcher for the Giants, Al Corwin, told me something fascinating about the buzzer Chadwick installed. Corwin was a rookie in 1951, and I was able to pinpoint the exact day they started using the buzzer by the date of his debut with the team. He told me he happened to join the Giants the very day of the meeting Durocher held on July 19, and actually arrived at the ballpark in the middle of this meeting where this crazy idea about stealing signs was being discussed. The next day, which was the day they began stealing signs, the great Cincinnati Reds pitcher Ewell Blackwell was pitching, and Corwin said that the first sounds of the buzzer in the right centerfield bullpen were so loud that he and his teammates almost fell off the bench because they were worried everyone would hear them. The next day they asked Chadwick to lower the sound of the buzzer. During the very next homestand, Chadwick collapsed while on the subway — it turned out that he had inoperable cancer. His brother Nat bought him a television, and he watched every Dodgers game for the rest of the season. He also watched the fates of the Dodgers and the Giants slowly converge — he knew what was going on but didn’t say anything to anyone except to a few people in the electrician’s union. He died a very heartbroken man one month to the day after his team lost on Bobby Thomson’s home run.

PH The weight of the secret, huh…

JP Exactly.

PH Many of the men involved in this scheme had wartime experience, which somehow enabled them to rationalize their behavior. Schenz and Franks looked at the sign stealing as “getting the edge,” that it was a part of the game of baseball, and the fact that it was being done by a mechanical contrivance didn’t seem to phase them. They were able to come to terms with that, weren’t they?

JP It’s an interesting point. Leo Durocher is credited as saying, “Nice guys finish last,” and he really believed in winning at all costs. Herman Franks told me that during the war, they spied on the Germans and the Japanese, and asked if we were wrong for doing that. Another thing that shaped Herman Franks is the fact that he was on the Dodgers when, in the 1941 World Series, the catcher Mickey Owen let a ball get by him, which led to the Yankees winning the World Series. Franks saw what this experience of losing did to Owen, and it influenced his behavior, and supported the notion that you do whatever it takes to win. Also, at the time, a World Series share was worth $5,000, which was equivalent to a minimum yearly salary, so this was a large sum of money and it helped them rationalize what they were doing.

The Dodgers and the Giants didn’t like each other at all — their heated rivalry is not some cliche, and it is honest to say that it transcended the ballfield. Bobby Thomson told me that the only Dodger he ever said anything to was Gil Hodges — the first basemen who was held in such high esteem – and that was only a “hello.” The teams didn’t talk to one another off the ballfield at all; they didn’t like each other and they didn’t want the other team to win. They wanted to defeat the other team soundly, and to even injure the other team, if possible. Durocher was known as a gruff and unpleasant man with a “win at all costs” attitude, and during his playing days would scream curses at people and file his spikes sharp in order to injure an opposing player while sliding into second base. He did whatever he could.

Franks was right out of the same mold, and, although Hank Schenz was just a bit player, he was famous around the league as a bench jockey who razzed everyone mercilessly. He would say anything, including race-baiting comments, to distract the other team. Sal Yvars, who was probably the most unpleasant player on that team, was a fiery, pepperpot of a man who was always getting into fights. In a way, he is vindicated by the publication of this story because he was the only one over the years who would hint that this scheme even existed, and, as it turns out, he was telling the truth. Finally, there was Abe Chadwick, the electrician, a tough guy who would launch into fisticuffs if anyone disparaged his team at all. So, these guys weren’t sweet guys — they were tough men who believed in winning at all costs, and they didn’t think twice about cheating. Ironically, the hero of the season, Bobby Thomson, was the exact opposite — he was the sweetest, most self-deprecating man — almost to a fault — and it preyed on him that the team was cheating.

PH Thomson and Ralph Branca will forever be linked by Thomson’s home run in the playoff game. Can you you talk a little about their relationship?

JP Their relationship is amazing, and people have always marveled at it. That playoff game was such an emotional experience for baseball fans — it was, in fact, traumatizing for many. But even though Branca would receive telegrams telling him to “drop dead,” he was able to shrug that off, and even attended game six of the World Series. Bobby Thomson was the exact opposite. He was made into a real hero. Open car parades took place in his hometown in Staten Island, and people were even naming their children after him.

The home run transcended the ballfield and embedded itself in the minds of literally millions of people — it was one of those moments everyone remembered exactly where they were when it happened. There were many moments in baseball prior to this that also had a hero and goat. One example is from the 1950 season, when Dick Sisler hit a home run off Don Newcombe, winning the pennant on the last day of the season for the Phillies, yet few remembers this moment, or Sissler and Newcombe.

The relationship Thomson and Branca deepened as a result of a few moments. One came during the sixth game of the World Series, when Branca was spotted by a photographer named Herb Scharfman, who saw a golden photo opportunity that would feature Branca and Thomson. He got them together and asked Branca to pose for the photo as if he were choking Thomson, so Branca placed his hands around Bobby’s neck and Scharfman took the picture. It was the first one ever taken of them paired together, and it got circulated all over.

A few months later, at the Baseball Writer’s Association of America dinner, the writers wrote a parody of a popular Tony Bennett recording called “Because of You,” and then asked Thomson and Branca to sing it. It was not a silly song, it was actually quite moving, and people literally started to cry at this dinner — including the president of the National League, Warren Giles. They sang the song again a few days later on the Ed Sullivan Show and from that point forward, these men were forever linked. While over the years they appeared together at events like baseball memorabilia shows, they never talked about the sign-stealing.

PH When did Branca learn about the Giants scheme to steal signs?

JP In 1954, after he was let go by the Dodgers and picked up by the Detroit Tigers. By then, his career had gone downhill, and he had pretty much reconciled himself to the fact that he would forever be known as the pitcher who gave up the home run to Bobby Thomson. A friend of Branca’s named Ted Gray had been told about the sign stealing by former Giants player Earl Rapp and Gray decided to tell Branca about this to help him feel better. Instead, by his own admission, he had become a very angry person. Suddenly, Branca felt that the home run wasn’t just unfortunate, it was unfair. Despite this, he could not bring himself to talk to Thomson about the sign stealing, and Thomson never said anything to Ralph about it, even though in 1962 rumors began to spread about how the Giants cheated. And so, Branca really experienced three different traumas; one was giving up the home run, the second was finding out that the Giants cheated, and the third was discovering that no one cared.

These men were strikingly different. Bobby Thomson was humble and self-deprecating, while Ralph Branca was the exact opposite — and a very proud man. If you didnt know anything about these men and saw them standing side by side, you would be hard pressed to know who had won and who had lost. Had it been the other way around, where Branca was the hero and Thomson the goat, they never would have been able to stand side by side. It is fascinating how, even in the moments right after the home run, their personalities shone through. Thomson was carried off the field on the shoulders of his teammates and became a national hero, appearing on the Perry Como Show that night, spritzed with champagne. Yet, minutes after he was literally hyperventilating, he criticizes himself for not being a better hitter. And even though Branca, meantime, was devastated by the moment — he literally doesn’t remember walking from the field to the clubhouse and openly wept on the steps of the dugout — he propped himself up and talked about how he threw a good pitch, just the kind that he wanted to throw. So Branca was the one propping himself up, while Thomson was the one putting himself down.

PH Thomson’s home run is the moment everyone remembers about the 1951 season. Can you talk a little bit about the events that led up to this?

JP I felt that in order to write this story properly, I would have to include details from the era that make it come alive. It was exciting for me because there were so many connections that were organic to the home run. For example, J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye was published that year, so I reread it and was reminded that Allie Caulfield’s baseball mitt not only had beautiful poems written on it, but also that Clem Labine wrote “Turn” on his mitt so he could remind himself to cover his pitching hand, which would prevent him from tipping off his pitches to the hitter. I wanted readers to know that on the very day Thomson hit his home run, October 3, 1951, the White House announced that the Russians exploded an atom bomb. A press conference was called that coincided with the eighth inning of the game, and one of the reporters covering it was Frank Bourgholtzer, who grew up in the same town as Thomson — in fact, Thomson had inherited his train set! And, here he is, watching the game, rooting for Thomson, when this situation with the Russians is being announced. While his colleagues are in the press room, typing up their lead for this enormous story, Bourgholtzer hears that Dark singled and Mueller singled and he watches Thomson hit the home run. He is so overwhelmed that he starts screaming, “That’s my boy! That’s my boy!” while President Truman is just a few rooms away meeting with J. Edgar Hoover.

Someone who didn’t benefit from the “red scare” that was taking root all over the country was the spy Julius Rosenberg, who at this time was on death row in Sing Sing Prison. Even though there could not have been anything worse for him than the announcement of the Russian atom bomb test, on this particular day he was most of all a despondent Dodger fan who, while listening to the game on death row, wrote his wife Ethel — who was also on death row — “Gloom of glooms. The dear Dodgers lost the penant [sic].” That very same night, Gordon Dean, the head of the Atomic Energy Commission, wrote in his journal how happy he was that the Bobby Thomson home run had gotten bigger headlines than the announcement that the Russians had exploded the atom bomb. So you can see the home run was a huge moment, and 55 years later people still remember exactly where they were when it happened.

Front page of the New York Times, October 4, 1951

PH You talked to an impressive sampling of people who had very vivid memories of the moment, including Don Dellilo, Arthur Miller, Sid Caesar, Warner Buffett, and Gerald Ford. Is there an experience that stands out for you?

JP My most exciting correspondence was with Arthur Miller, who wrote me a beautiful letter that described where he was and what he was doing when Thomson hit the home run. He was on an elevator heading up to see the producer of “Death of a Salesman,” Kermit Bloomgarden. He described Kermit as having “a very quiet if not lugubrious personality,” yet “here he was, screaming at two or three people in the office and red in the face between laughter and tears.” He also writes about seeing three smoking cigars resting in an ash tray on this man’s desk, and seeing this man just bouncing around the room in excitement. Then he writes, “I was not any longer a baseball fan, but when I heard what had happened I felt the axis of the world had shifted slightly and we must all be happy for at least five minutes.” And I thought about how true it was that this moment embedded itself in the minds of everyone — even those who were not fans took note of it and realized that it was historic. It is a moment that many people have listed alongside John Kennedy’s assassination, Pearl Harbor, and now September 11th as shared experiences the entire country took note of. There are a number of major reasons for this, and one of the most significant is that this playoff series between the Dodgers and the Giants was the first ever nationally televised sporting event, so everyone followed it — squeezing into the room of the guy down the street who owned a television, or standing outside storefronts to watch. That Thomson provided a moment up to this historic telecast is an incredible thing.

PH Yes, all that went on in that inning was remarkable — the rally; Charlie Dressen calling down to his bullpen coach Clyde Sukeforth to ask who looks better between Branca and Carl Erskine; Don Mueller breaking his ankle while sliding into third base; Ernie Harwell in the television booth; Russ Hodges in the radio booth

JP When I talked with Thomson, he was very open about the stealing of signs that went on throughout the latter part of the 1951 season, and also about earlier in the game, but when it came to talking about his home run, he always said that he wasn’t aware of anything or anyone else in the ballpark other than himself. He spoke about Mueller’s injury distracting him, how it took his mind off the game, and what I think he meant by that was that he wasn’t aware of anyone else in the ballpark except him, that he wasn’t even aware of Sal Yvars relaying the signals from right field. Yvars told me that he did, in fact, relay the signal to Thomson. When I asked Thomson whether or not he got a signal for the home run pitch, he equivocated. To me, it wasn’t really that important whether or not he got the sign for that pitch, the fact is he still hit the home run and they were still cheating. But what I cared most about was the effect keeping this secret had on him, and how it preyed on him and Branca all those years.

You also mentioned the call down to the bullpen, and one of the things that was exciting for me — at least from a baseball fan’s point of view — was setting the record straight. There are so many details people have gotten wrong over the years as myth has accrued to this game and this moment. For example, people have always said that Dressen, the Dodger manager, made a big mistake when he brought in Branca rather than Erskine. While I realize Dressen’s ego often got in the way of making proper decisions — he is a huge goat in this book — bringing Branca in was not one of his mistakes. Even though Thomson hit a home run off Branca two days earlier in Ebbets Field, Branca’s record was much better against Thomson than Erskine’s was. Erskine’s record was dreadful — Thomson had hit .545 off Erskine. I researched the records of all the pitchers available to Dressen, and the best was Preacher Roe, who had faced Thomson fifty times and held him to a .220 average. The Dodgers had a statistician named Allan Roth — who was way ahead of his time in terms of compiling statistical match-ups — and he wanted to share this information with Dressen. Roth was well aware of the Roe versus Thomson matchup, but Dressen didn’t want to have anything to do with him. Dressen actually banished Roth to the press box.

PH The Giants also had a statistician, Jack Carter, but his information was embraced by Leo Durocher…

JP That’s right. No one really knew about Carter, who loved baseball and baseball statistics. He came up with a system that judged the effectiveness of lineups — he was all about making up the lineup based on matchups. Durocher ended up hiring him and had Thomson batting sixth that day, which was the spot that kept coming up at critical times throughout the game. So, yes, one manager embraced statistics and the other didn’t, and the rest, as they say, is “history.”

PH Thomson drove in six of the eight runs the Giants scored during the playoff series, but he also was set up to be the goat of the deciding game when he ran himself into a double play…

JP Yes. He hit a single and tried to stretch it into a double, but he didn’t look ahead — he just put his head down and ran towards second — and there they were, these two men on base. Not only that, he hadn’t fielded particular well during the game — there were some hot smashes down the line that he didn’t stop. So he was the goat of the game, even though he had two hits and a sacrifice fly leading up to the home run. But, no one remembers that.

PH The game is also famous for the announcers who called it…

JP There were seven announcers, and I tracked them down one at a time — including an announcer by the name of Nat Allbright, who did a simulated broadcast of the game. At the beginning of the game, Gordon McClendon talked about how if there was a goat in the game, his name would “echo down the corridors of time,” and, boy, was he ever right! If you visit my website, JoshuaPrager.com, you can hear the radio calls of the game — not only of Russ Hodges making the famous, “The Giants Win the Pennant!” call, but also the one by McClendon. Red Barber’s call is fascinating because he was a very “by the book” announcer — he didn’t believe in embellishing. He was calling the game for the heartbroken Dodger fans and, after his call of the home run, waited 59 seconds — just long enough for the crowds’ scream to subside — before speaking again. Even though this was not preserved on tape, I was told by several who remember that in an effort to provide his audience perspective he brought up that people were dying in the Korean War. That was helpful to his audience, and it showesthe degree of tragedy this was for fans of the Dodgers.

PH Your book includes 120 pages of footnotes and includes some amazing information. I am a member of the Pacific Coast League Historical Society, but I didn’t know that Thomson played for for Roma Vintners and Ben’s Golden Glow in the Alameda Winter League in 1945! You did an unbelievable amount of research for this book…

JP The book took me six years to write. I believe very much in documenting sources, and particularly in this case, where I was writing about something so many people care about. And, informing them that the story they know is somewhat different from what actually transpired, it was important that it be well documented. I wanted readers to be able to take this story as fact so that they could then focus on the more important thing — the effect that this had on these men.

.

___________

.

Photo Frank Rino

“And not only had Thomson struck his blow at just the right time and in just the right place. But baseball’s perfect storm had been bottled in perfect fashion. There was its radio call, Russ Hodges conveying sublimely the ineffable. There was its newsreel, silent footage of a ball seen launched but never landed. There was its TV broadcast, which though not taped had carried the great shot unprecedented distance, vanguard of live nationally televised sport, what tens of millions had watched together. There was its write-up, a home run channeled through the classical Red Smith. There was its preferred photograph, a ball stilled on its way to left. There were its nicknames, the ‘Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff,’ the ‘Shot Heard Round the World,’ (time trimming from each an extraneous word). And of course there were its twin protagonists, Thomson and Brana astride a home run. Thus preserved, the shot turned what Henri Cartier-Bresson defined a ‘decisive moment.’ Wrote the photographer in 1952: ‘It is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as a precise organisation of forms, which give that event its proper expression'”

– Joshua Prager

.

*.

The Echoing Green:

The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World

by

Joshua Prager

.

.

.

.

About Joshua Prager

.

PH Who was your childhood hero?

JP I had a few baseball heroes when I was a kid. One was Graig Nettles, the Yankee third baseman. I was always making myself dive like he did. Lou Gehrig was another. I used to sleep under a picture of him. I always admired him — not just for his baseball skills — but also for the type of person I was told he was. My favorite author when I was a little kid was Roald Dahl. I loved reading his books. As I got older, I found out he was a rabid anti-Semite, so I guess there is a lesson in there somewhere. Maybe it is best not to learn too much about your heroes.

.

*

Joshua Prager grew up in New Jersey and studied music theory at Columbia College. He is a senior special writer at the Wall Street Journal and lives in New York City.

.

.

.

Interview took place on November 24, 2006

.

*

.

If you enjoyed this interview, you may want to read our interview with Jackie Robinson biographer Scott Simon.

.

.

# Text from the publisher

.

.

.